|

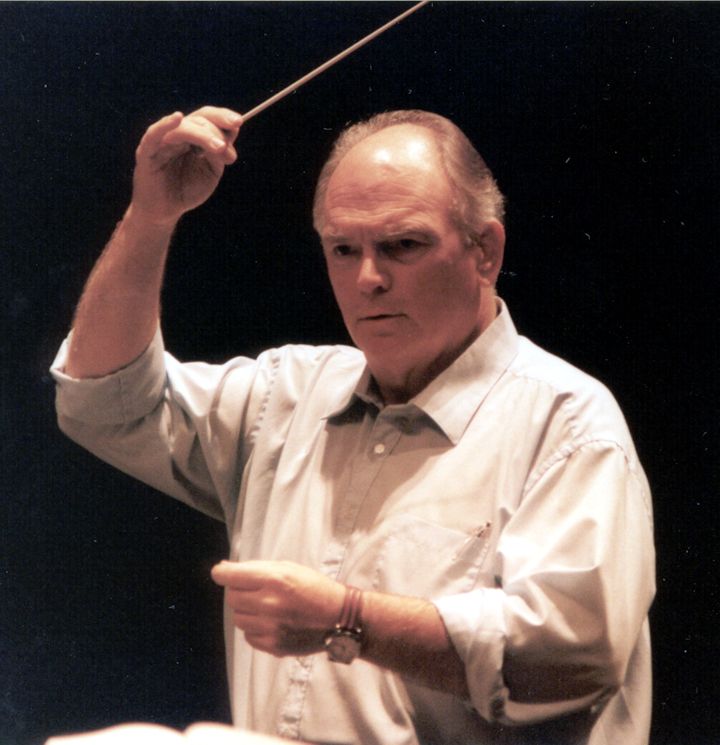

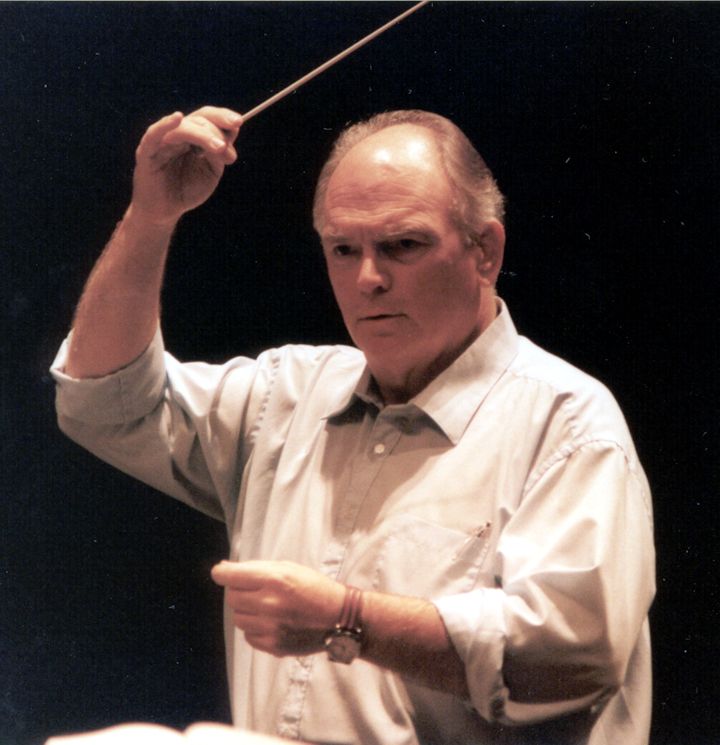

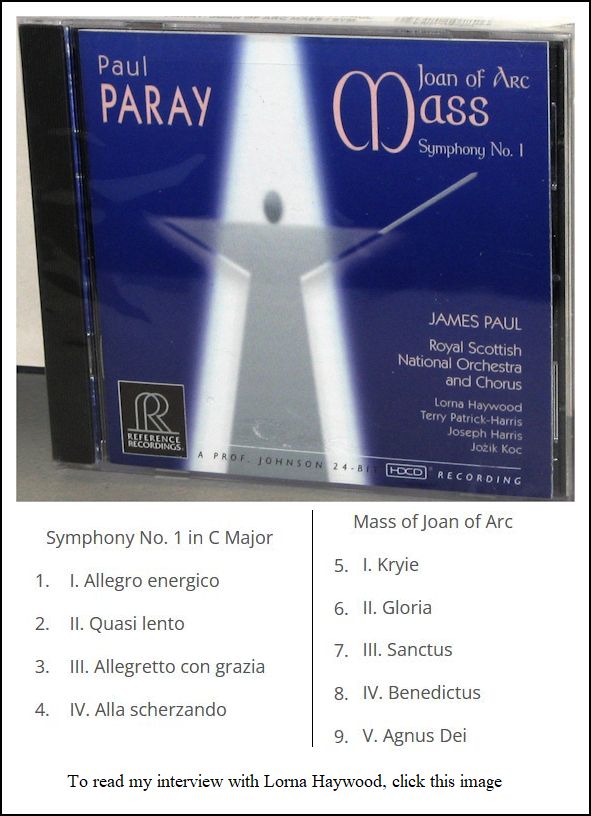

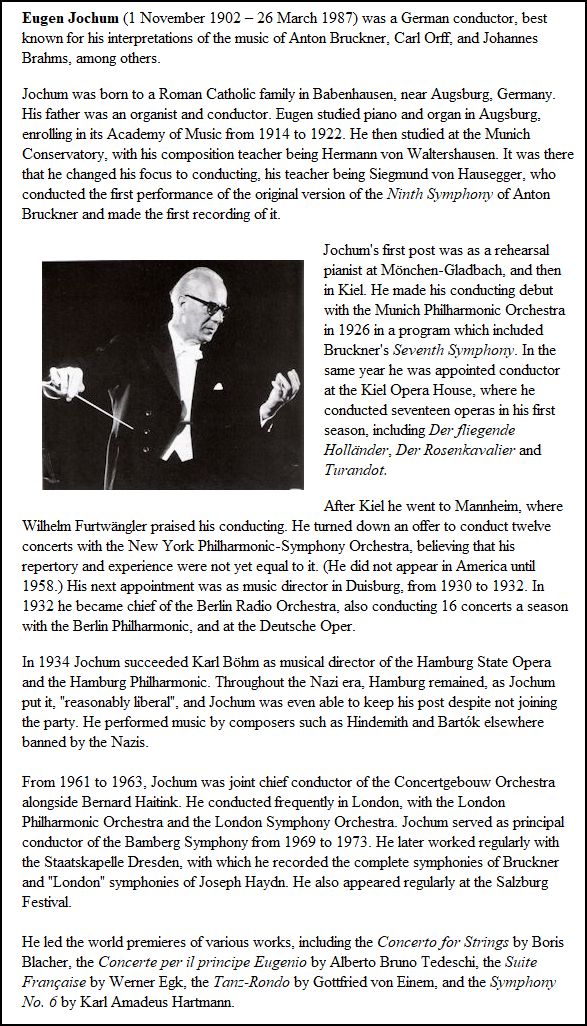

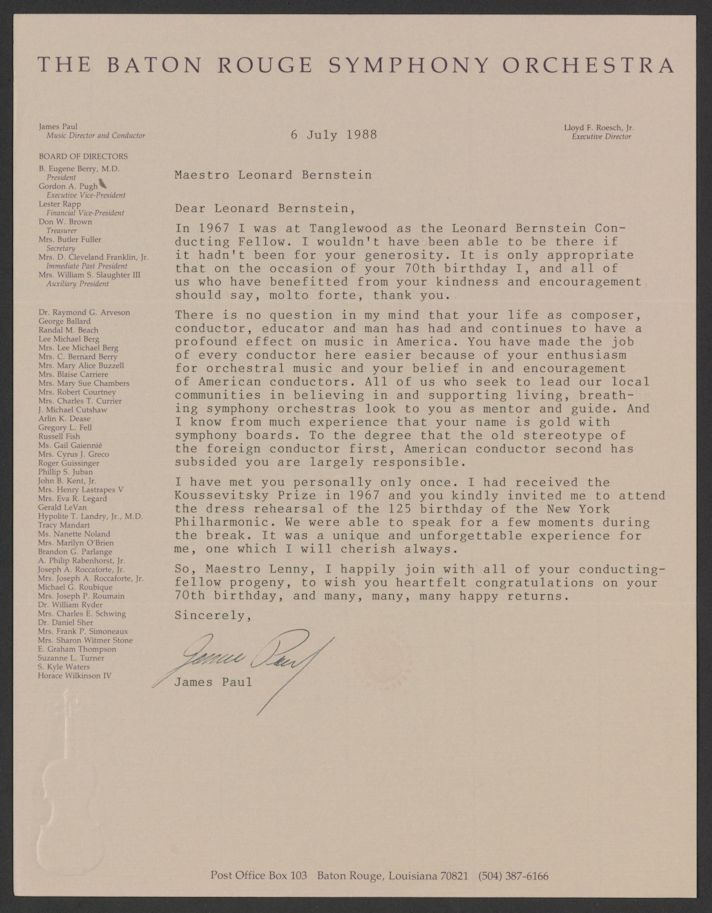

James Paul (born October 17, 1940, in Forest Grove, Oregon) is an American conductor. Paul studied voice at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music and the Mozarteum in Salzburg, while conducting various student and professional organizations. Following his studies he was awarded the Serge Koussevitsky Memorial Conducting Prize presented by Erich Leinsdorf at the 1967 Tanglewood Music Festival. Paul then served as conducting fellow with the St. Louis Symphony, and conductor of the Bach Society of St. Louis. He subsequently took posts as associate conductor of the Kansas City Philharmonic and Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra. In 1981 Paul was appointed music director of the Baton Rouge Symphony. During the fifteen years under his leadership, the orchestra became a well-disciplined, highly recognized artistic entity. The Symphony shared the 1983 American Symphony Orchestra League award for most innovative programming with the Brooklyn Philharmonic and was also the only regional orchestra featured on the WFMT Fine Arts Network's Music in America series. In 1984, Paul founded the Baton Rouge Symphony Chorus. A high point of his tenure was the orchestra's performance on October 22, 1988, at Carnegie Hall in New York City. The program included Chadwick's Jubilee from Symphonic Sketches, Sibelius’ Symphony No. 2 and Beethoven's Piano Concerto Nr. 4 with soloist Abbey Simon. The concert received excellent reviews in both the New York and Louisiana newspapers. Following his final concerts in February 1998, Paul was named Conductor Emeritus, the only conductor so honored by the orchestra in its 50-year history. Parallel to his tenure in Baton Rouge, Paul served for several years as music director of the Ohio Light Opera (conducting Gilbert and Sullivan and other light operas) and principal guest conductor of the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra. As a guest conductor he has led the Chicago Symphony, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Symphonies of Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Houston, Dallas, Seattle, San Diego, San Antonio, New Jersey, Oakland, Honolulu, Kansas City, Jacksonville and Detroit. Recent past engagements include the Houston Symphony, the Singapore Symphony, the National Symphony, the Minnesota Orchestra, the Baltimore Symphony, the San Francisco Symphony, the Saint Louis Symphony, the Buffalo Philharmonic, the Calgary Philharmonic, Symphony Nova Scotia (Halifax), Vancouver Symphony, and the Utah Symphony. In 1997, Paul recorded Paul Paray's Joan of Arc Mass and First Symphony with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and Chorus. This recording received a Grammy nomination for "Best Choral Performance." Paul was the co-founder and classical music director and conductor

of The Shedd Institute's Oregon Festival of American Music from 1997 to

2007, the artistic director of the Sewanee Summer Music Festival from

2006 to 2009, and served for six seasons as principal guest conductor of

the Grant Park Music Festival. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

BD: Once you decide on doing a piece, does the idea of doing it outside change your interpretation at all, or would you do it the same outside as you would do it say, in Orchestra Hall?

| Fact Check: Upon entering

office in 1981, the incoming Reagan administration intended to push Congress

to abolish the NEA completely over a three-year period. Another proposal

would have halved the arts endowment budget. However, these plans

were abandoned when the President's special task force on the arts and

humanities discovered ‘the

needs involved and benefits of past assistance,’

concluding that continued federal support was important. While

the department's budget decreased from $158.8 million in 1981 to $143.5

million, by 1989 (the end of Reagan’s second term) it

was $169.1 million, the highest it had ever been. Also of note: After

being created by an act of Congress and signed into law by Lyndon Johnson

in September of 1965, Richard Nixon’s early endorsement

of the arts benefited the National Endowment in several ways. The

budget not only increased, but more federal funding became available for

numerous programs within the agency. Between 1965 and 2008, the agency

made in excess of 128,000 grants, totaling more than $5 billion. |

© 1990 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on July 16, 1990. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following day, and again in 1997, and three times in 2000. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.