| Ellen Zwilich (born in 1939) is

the recipient of numerous prizes and honors, including the 1983 Pulitzer

Prize in Music (the first woman ever to receive this coveted award), the

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Chamber Music Prize, the Arturo Toscanini Music

Critics Award, the Ernst von Dohnanyi Citation, and Academy Award from the

American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Guggenheim Fellowship, four Grammy

nominations, and, among other distinctions, she has been elected to the Florida

Artists Hall of Fame and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1995,

she was named to the first Composer's Chair in the history of Carnegie Hall,

and she was designated Musical America's Composer of the Year in 1999. A more complete profile from her publisher appears at the bottom of this webpage. Note that names which are links on this page refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Why not, indeed? [Laughs]

This was written for the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Charles

Wadsworth, who’s their Artistic Director, and I met about this commission.

They have a rather large complement of Society members, and he was telling

me this possibility, that possibility. I wanted to write a large scale

work for a sizable number of players, and one of the ideas he threw out

was, “We have the Emerson String Quartet in residence and we have another

quartet of Society members.” I had kind of an immediate flash, and

thought that was a wonderful sounding idea!

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Why not, indeed? [Laughs]

This was written for the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Charles

Wadsworth, who’s their Artistic Director, and I met about this commission.

They have a rather large complement of Society members, and he was telling

me this possibility, that possibility. I wanted to write a large scale

work for a sizable number of players, and one of the ideas he threw out

was, “We have the Emerson String Quartet in residence and we have another

quartet of Society members.” I had kind of an immediate flash, and

thought that was a wonderful sounding idea! |

Excerpts from two reviews

of the Double Quartet

[The world premiere and the Chicago performance] CONCERT: NEW WORK BY ZWILICH By DONAL HENAHAN Published in The New York Times, October 22, 1984 For the first concert of its regular subscription season yesterday at Alice Tully Hall, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center put together a program without a weak link. Besides sharply honed performances of three familiar masterpieces, there was the world premiere of Ellen Taaffe Zwilich's Double Quartet for Strings, a work commissioned by the society. Although it kept fast company in its first appearance, Mrs. Zwilich's score not only held up its head but made a powerful impression throughout its 4-movement, 18-minute length. Mrs. Zwilich, you may recall, won last year's Pulitzer Prize for music with her 'Three Movements for Orchestra.' A 46-year- old former student of Elliott Carter and Roger Sessions, she also is a violinist who studied with Ivan Galamian and Richard Burgin and played in the American Symphony Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski. Her credentials are all in place. However, credentials do not count for much once the music begins. What did count in Mrs. Zwilich's piece, beyond the expert use of compositional devices and the clever manipulation of string techniques and sonorities, was the sense of concentrated emotion that it conveyed. This was a composer intent on communing with her audience and in full command of the technical means to do so. The score took a variety of formal approaches to the problem of combining and contrasting the two string quartets, one of them the resident Emerson String Quartet and the other a foursome drawn from the society's general roster of artist-members. The first movement, which treated the eight players as a cohesive unit, specialized in Stravinskyish ostinatos, motoric repetitions of simple rhythmic ideas both plucked and bowed. Meanwhile, supple melodic lines intertwined overhead. There was strength and vigor in the music, as well as a striking way of blending dissonance and consonance in what suggested patterns of deep, heavy breathing. An equally weighty, brooding Lento pitted instruments against one another. This was followed by an intense Allegro Vivo that suggested Bartók's middle quartets as an inspiration. The Adagio finale, though simpler in means than what went before it, breathed the same air. The dissonance level remained high, but the Adagio did not at any time scorn sensuous string tone. In fact, throughout her piece Mrs. Zwilich displayed clear-eyed maturity and a rare sense of balance. She writes music that pleases the ear and yet has spine. * *

* * *

2 String Quartets Mesh Beautifully Published in the Chicago Tribune, January 14, 1986 By John von Rhein, Music critic. String quartet playing is supposed to be a harmonious business, although there is no telling what will happen when eight talented, temperamental string players, half of them men, half women, decide to pool musical resources. That is precisely what occurred Monday evening at the Civic Theatre, where the Orford String Quartet and the Colorado Quartet played a more-or-less joint concert under the auspices of Chamber Music Chicago. The fact that the four male musicians of the Orford are Canadian while the four young women of the Colorado are Americans led one to expect a kind of international battle of the sexes. Apart from the third movement of Ellen Taaffe Zwilich`s Double Quartet for Strings, in which the two groups purposely squared off in heated antiphonal dialogue, however, no such battle ever took place. In fact, the ensembles turned out to be nicely complementary in style, a virtue that the Zwilich work managed to exploit to richly resonant advantage. |

BD: Is music art, or is music entertainment?

BD: Is music art, or is music entertainment? BD: Let me ask you about some of the works of yours

which have been recorded thus far.

BD: Let me ask you about some of the works of yours

which have been recorded thus far.  ETZ: No, I don’t do any teaching. I do like

to do things like this, where I come out and do a meet-the-composer kind of

program, and meet audiences. Going to performances and working on performances

is a very important part of my work.

ETZ: No, I don’t do any teaching. I do like

to do things like this, where I come out and do a meet-the-composer kind of

program, and meet audiences. Going to performances and working on performances

is a very important part of my work. BD: One other thing I noticed when they were rehearsing

the pieces earlier today was where the two violins were playing in unison

for a moment on a sustained note, it sounded completely different when the

vibrato was together and when the vibrato was separate. Is that anything

that you would want to control or try to control in performance, or would

you just let it happen?

BD: One other thing I noticed when they were rehearsing

the pieces earlier today was where the two violins were playing in unison

for a moment on a sustained note, it sounded completely different when the

vibrato was together and when the vibrato was separate. Is that anything

that you would want to control or try to control in performance, or would

you just let it happen?| At a time when the musical offerings

of the world are more varied than ever before, few composers have emerged

with the unique personality of Ellen Taaffe Zwilich. Her music is widely known

because it is performed, recorded, broadcast, and – above all – listened to

and liked by all sorts of audiences the world over. Like the great masters

of bygone times, Zwilich produces music "with fingerprints," music that is

immediately recognized as her own. In her compositions, Ms. Zwilich combines

craft and inspiration, reflecting an optimistic and humanistic spirit that

gives her a unique musical voice. Ellen Zwilich is the recipient of numerous prizes and honors, including the 1983 Pulitzer Prize in Music (the first woman ever to receive this coveted award), the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Chamber Music Prize, the Arturo Toscanini Music Critics Award, the Ernst von Dohnányi Citation, an Academy Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Guggenheim Fellowship, 4 Grammy nominations, the Alfred I. Dupont Award, Miami Performing Arts Center Award, the Medaglia d'oro in the J.B. Viotti Competition, and the NPR and WNYC Gotham Award for her contributions to the musical life of New York City. Among other distinctions, Ms. Zwilich has been elected to the Florida Artists Hall of Fame, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1995, she was named to the first Composer’s Chair in the history of Carnegie Hall, and she was designated Musical America’s Composer of the Year for 1999. Ms. Zwilich, who holds a doctorate from The Juilliard School, has received honorary doctorates from Oberlin College, Manhattanville College, Marymount Manhattan College, Mannes College/The New School, Converse College, and Michigan State University. She currently holds the Francis Eppes Distinguished Professorship at Florida State University.

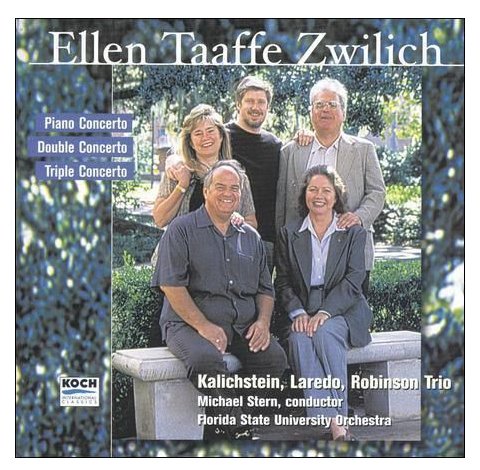

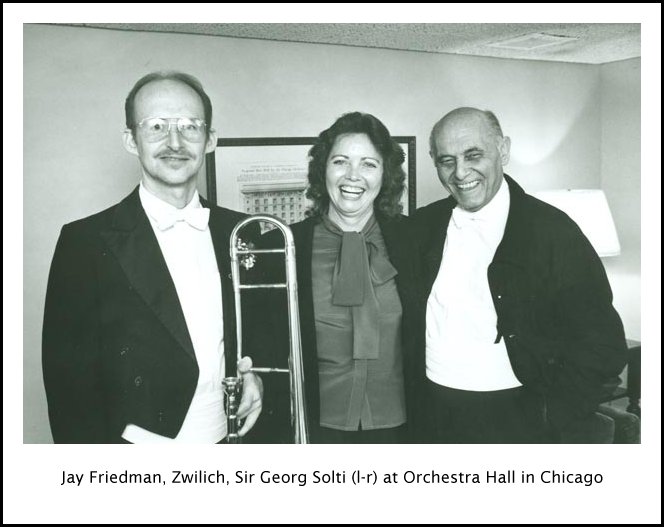

A prolific composer in virtually all media, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich’s works have been performed by most of the leading American orchestras and by major ensembles abroad. Her music first came to public attention when Pierre Boulez conducted her Symposium for Orchestra at Juilliard (1975), but it was the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for the Symphony No. 1 that brought her instantly into international focus. Commissions, major performances and recordings soon followed: the Symphony No. 2 (Cello Symphony), premiered by Edo de Waart and the San Francisco Symphony; Symphony No. 3, written for the New York Philharmonic’s 150th anniversary; Symphony No. 4 "The Gardens" (with chorus), commissioned by Michigan State University and the subject of a PBS documentary seen nationally; the Juilliard-commissioned Symphony No. 5 (Concerto for Orchestra) premiered at Carnegie Hall under James Conlon's direction [shown in photo above]; the string of concertos commissioned and performed over the past two decades by the nation’s top orchestras — for Piano (Detroit Symphony under Günther Herbig), Trombone (Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Sir Georg Solti) [soloist Jay Friedman is shown in photo below], Flute (Boston Symphony Orchestra, Seiji Ozawa), Oboe (Cleveland Orchestra, Christoph von Dohnányi), Violin and Cello (Louisville Orchestra, Lawrence Leighton Smith), Bass Trombone (Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Daniel Barenboim, with soloist Charles Vernon), French Horn (Rochester Philharmonic, Lawrence Leighton Smith), Bassoon (Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Lorin Maazel), Trumpet (San Diego Symphony, JoAnn Falletta), Triple Concerto for Piano, Violin and Cello (Minnesota Orchestra, Zdenek Macal), Violin (Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Hugh Wolff), and Millennium Fantasy for Piano (Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Jesús López-Cobos). Ms. Zwilich’s most recent concertos include the Clarinet Concerto (2002-2003), written for the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and the Buffalo Philharmonic, conducted by JoAnn Falletta (chamber and orchestral versions, respectively) with soloist David Shifrin; and Rituals (2004) for 5 Percussionists and Orchestra, premiered by IRIS Orchestra under Michael Stern, featuring the renowned Nexus percussion ensemble.

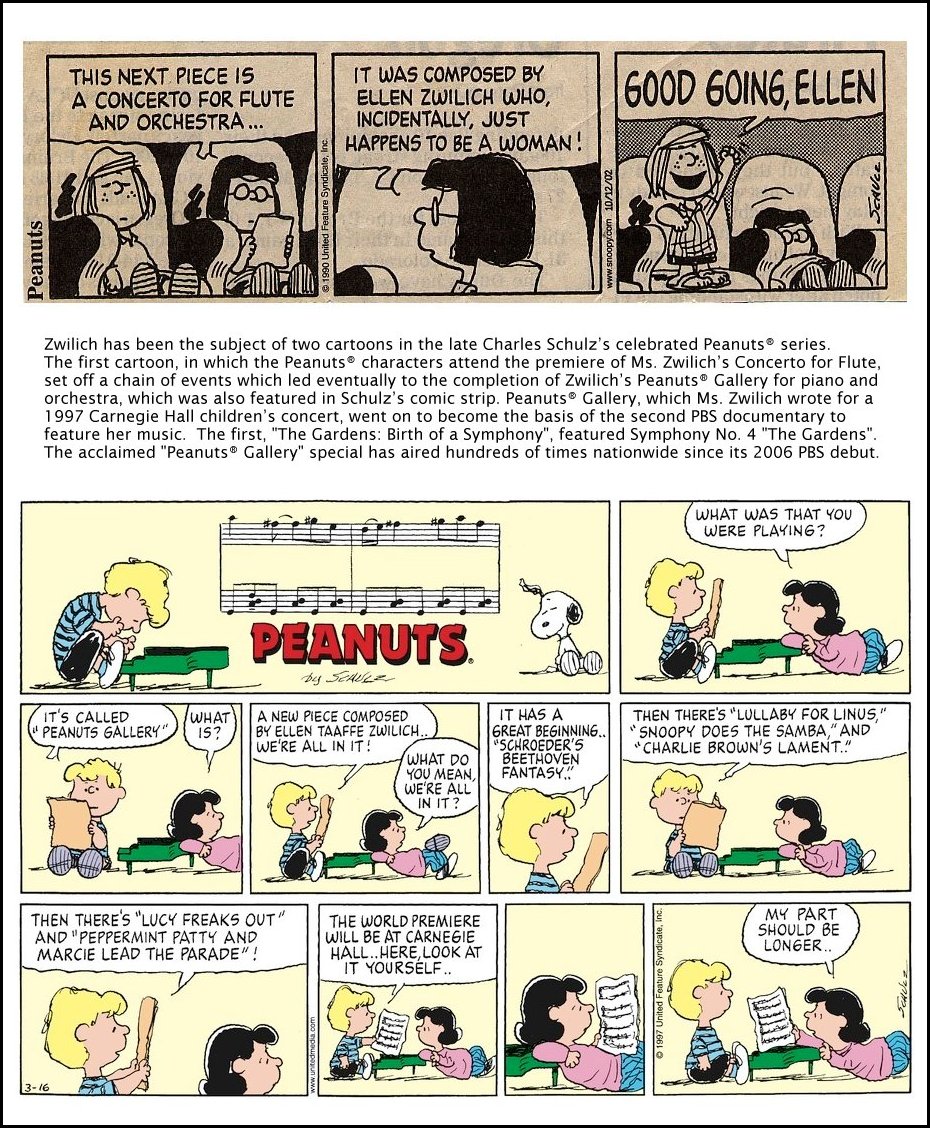

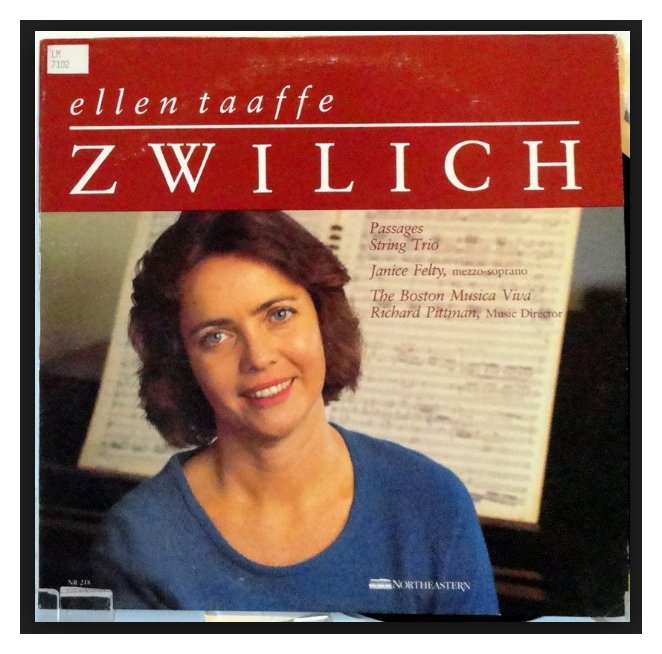

Ms. Zwilich’s orchestral essay Symbolon was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic expressly to receive its world premiere in what was then Leningrad. Conductor Zubin Mehta subsequently performed it in Europe, Asia and America and recorded it on the New World label. Carnegie Hall’s 1997 family concert series featured Peanuts® Gallery for piano and orchestra, a work based on Charles Schulz’s Peanuts® characters. Millennium Fantasy for Piano and Orchestra, a commission by a consortium of 27 orchestras, was premiered in September, 2000, by Jeffrey Biegel and the Cincinnati Symphony under Jesús López-Cobos. At the premiere, the mayor of Cincinnati issued a proclamation naming September 23, 2000 "Ellen Taaffe Zwilich Day", and presented Ms. Zwilich with the Keys to the City. Ms. Zwilich’s chamber works have been commissioned by the Boston Musica Viva (Chamber Symphony, Passages), the Abe Fortas Memorial Fund of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, 92nd Street Y and San Francisco Performances (Piano Trio), the New York State Music Teachers Association (Divertimento), the McKim Fund in the Library of Congress (Romance for Violin), the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival and Chamber Music Northwest (Clarinet Quintet), the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center (Double Quartet and Clarinet Concerto), Carnegie Hall (String Quartet No. 2), Ruth Eckerd Hall for Itzhak Perlman (Episodes for Violin and Piano), the Saratoga Chamber Music Festival (Oboe Quartet), and California EAR Unit (LUVN BLM). The 2007-2008 concert season saw the premiere of Quintet for Alto Saxophone and String Quartet, commissioned by a consortium comprising Arizona Friends of Chamber Music, the Chamber Music Society of Detroit, Fontana Chamber Arts, and Michigan State University. Zwilich has been the subject of two cartoons in the late Charles Schulz’s celebrated Peanuts® series. The first cartoon, in which the Peanuts® characters attend the premiere of Ms. Zwilich’s Concerto for Flute, set off a chain of events which led eventually to the completion of Zwilich’s Peanuts® Gallery for piano and orchestra, which was also featured in Schulz’s comic strip. Peanuts® Gallery, which Ms. Zwilich wrote for a 1997 Carnegie Hall children’s concert, went on to become the basis of the second PBS documentary to feature her music (the first, "The Gardens: Birth of a Symphony", featured Symphony No. 4 "The Gardens"). The acclaimed "Peanuts® Gallery" special has aired hundreds of times nationwide since its 2006 PBS debut, and will be rebroadcast during the 2007-2008 season. Many of Ellen Taaffe Zwilich’s works have been issued on recordings, and Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians [8th edition revised by Nicholas Slonimsky] states: "There are not many composers in the modern world who possess the lucky combination of writing music of substance and at the same time exercising an immediate appeal to mixed audiences. Zwilich offers this happy combination of purely technical excellence and a distinct power of communication." -- Biography from Theodore Presser

Company (text only - photos and links added for this website presentation)

|

This interview was recorded at her hotel in Chicago on January 13,

1986. Portions were used (with recordings) on WNIB a few weeks later

and again at the end of that year, as well as in 1989, 1994 and 1999.

A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern Univeristy. The transcription

was made and posted on this website late in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.