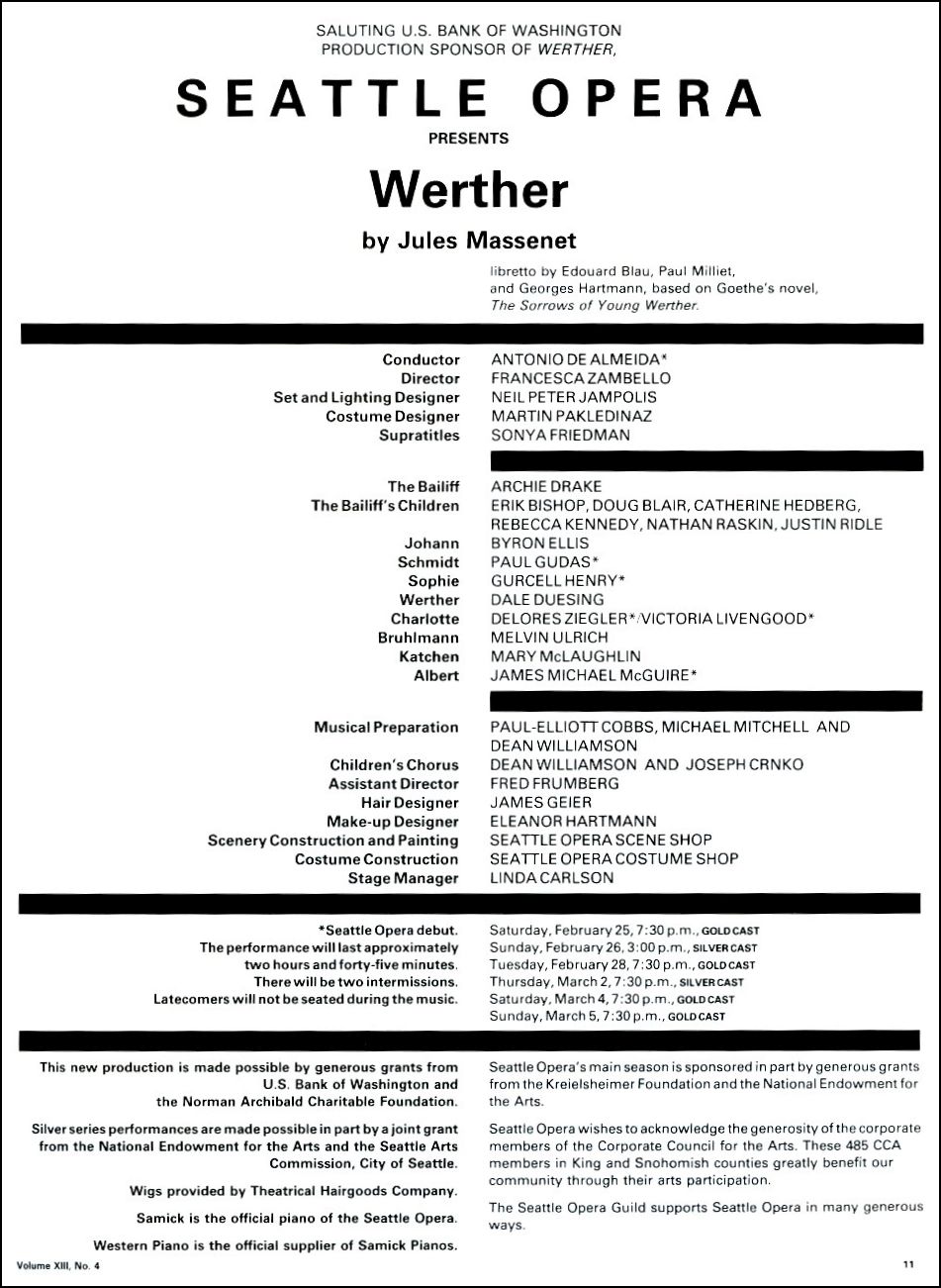

American mezzo-soprano Delores Ziegler has been heralded as "the mezzo we have been waiting for" by Martin Bernheimer in the Los Angeles Times. Her career takes her to every major theater in the world and into collaboration with the great directors and conductors of our time. Many of these extraordinary performances have been recorded and released as audio recordings and on video and film. With a repertoire that extends from bel canto to verismo, Ziegler has appeared in the world's greatest opera houses. At the Vienna Staatsoper, she made a debut as the Composer in Ariadne auf Naxos, returned for Idamante in a new production of Idomeneo, for Dorabella in a new Cosi fan tutte, and for Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier. At Teatro alla Scala she has opened the season as Idamante in a new production of Idomeneo, as well as having appeared as Dorabella, Romeo in I Capuleti e I Montecchi and Meg Page in a new production of Falstaff. She opened the prestigious Salzburg Festival as Sextus in a new staging of La Clemenza di Tito. At the Glyndebourne Festival she was heard as Dorabella and at the Bastille in Paris she sang Cherubino and Idamante. Highlights of her many appearances in Germany include the Composer

in a new production of Ariadne auf Naxos in Munich, Marguerite

in a new staging of La Damnation de Faust in Hamburg, and

Salieri's Falstaff in a new production by Cologne. Other European

appearances have included the Florence May Festival, where she sang

Idamante, Octavian and Dulcinée in Massenet's Don Quixotte,

Athens Festival for her first Gluck's Orfeo, and Dresden for

a rarity, Bertoni's Orfeo [shown below].

See my interviews with Cecilia Gasdia, and Bruce Ford

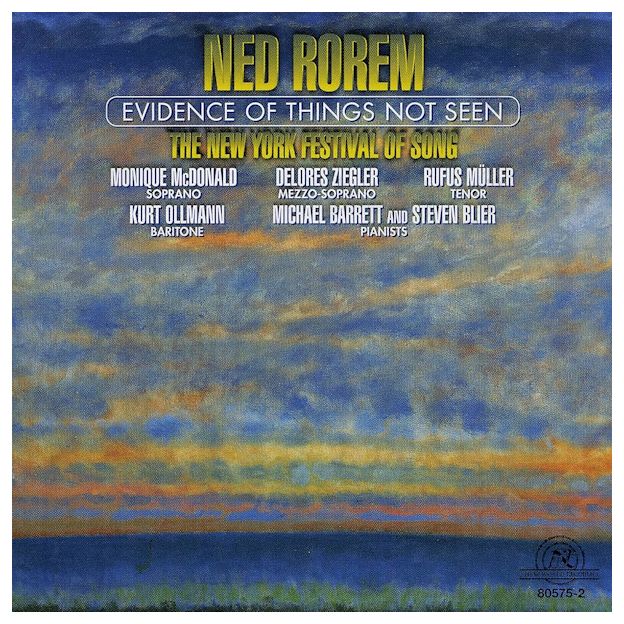

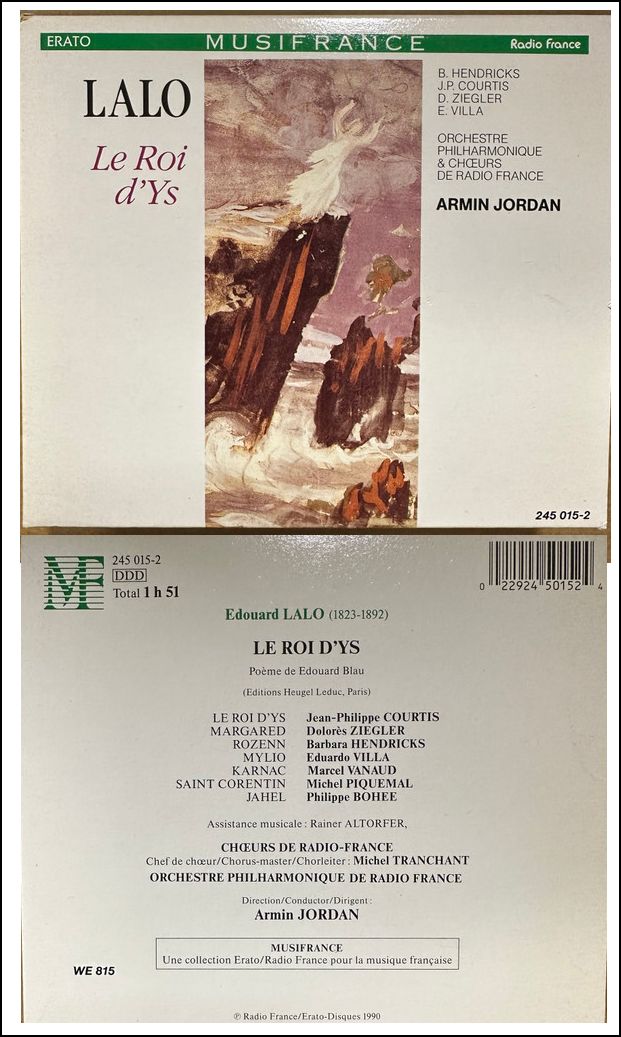

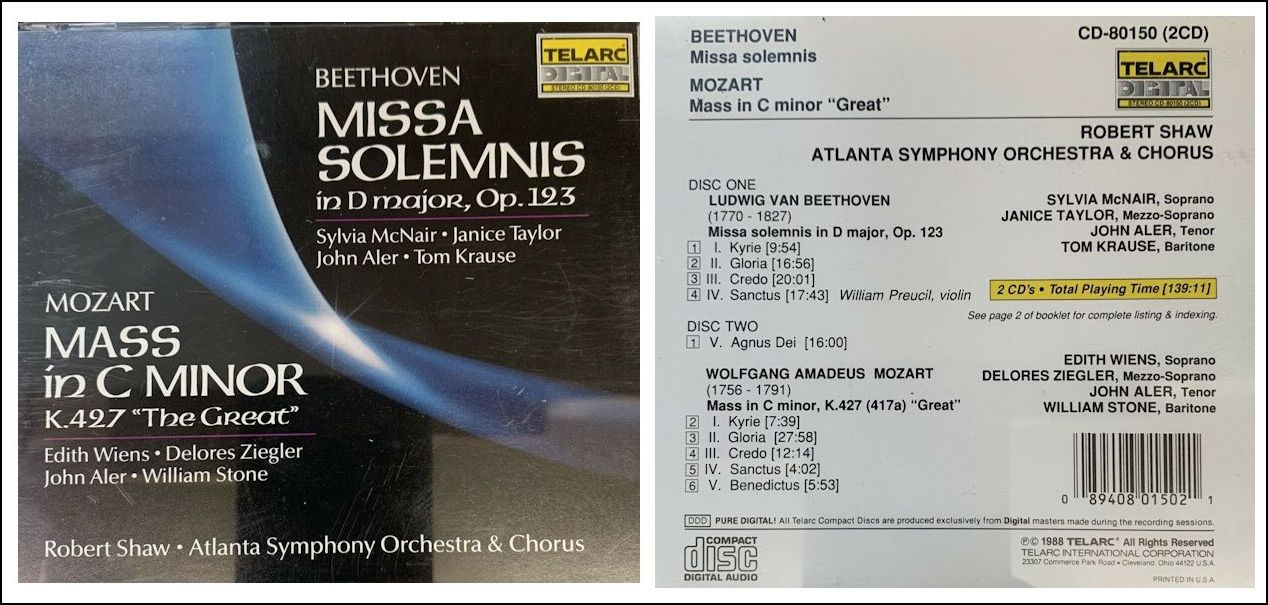

On January 6, 1986, Ziegler was featured in the initial "Pavarotti, Plus! - Live from Lincoln Center" PBS Television Special. Ziegler had the honor of making her Carnegie Hall debut as soloist in the Rossini Stabat Mater with Riccardo Muti and the Philadelphia Orchestra, this in Maestro Muti's last performance in America as music director of that prestigious orchestra. She has also appeared with orchestras throughout the United States, Canada, Europe and Japan. With London's BBC Symphony she sang Wagner's Wesendonck Lieder; with Santa Cecilia in Rome the St. John Passion and at Aix-en-Provence and in Venice, the Rossini Stabat Mater. She is a gifted Lieder singer and has appeared in that capacity in such cities as Paris, Florence, Vienna, Cologne and Bonn. In 1992 she made her New York City recital debut in Carnegie Hall's Weill Recital Hall Series. Ziegler has a discography of twenty-one recordings that includes the Mozart Requiem, Mozart's Great Mass and the Mahler Symphony No. 8 on Telarc with Robert Shaw and the Atlanta Symphony; Beethoven's Ninth Symphony with Riccardo Muti and the Philadelphia Orchestra on EMI; the Bach B-minor Mass with Nikolaus Harnoncourt on Teldec; both the Boccherini and the Pergolesi Stabat Maters on Frequenz conducted by Claudio Schimone; and the Mozart Coronation Mass on Deutsche Grammophon with James Levine and the Berlin Philharmonic. In addition to the two Così sets, Ziegler's complete opera recordings include two of La Clemenza di Tito – one as Sesto conducted by Riccardo Muti on EMI and one as Annio with Nikolaus Harnoncourt on Teldec; the title role in Bertoni's L'Orfeo with Claudio Scimone on Frequenz; Margarad in Lalo's Le Roi d'Ys with Armin Jordan on Erato Disque; Fatima in Weber's Oberon with James Conlon on EMI; and Meg Page in Falstaff with Riccardo Muti on Sony Classical. Ziegler recently recorded Sara in Roberto Devereux and Giovanna Seymour in Anna Bolena for the Nightingale label with Edita Gruberova, both conducted by Elio Boncompagni. Her most recent CD is Ned Rorem's song cycle The Evidence of Things Not Seen; she took part in the 1997 world premiere of this work in Carnegie Hall's Weill Recital Hall. [Many of her recordings are shown on this webpage.] == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

See my interview with Janice Taylor

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 12, 1993. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1995 and 1996. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.