|

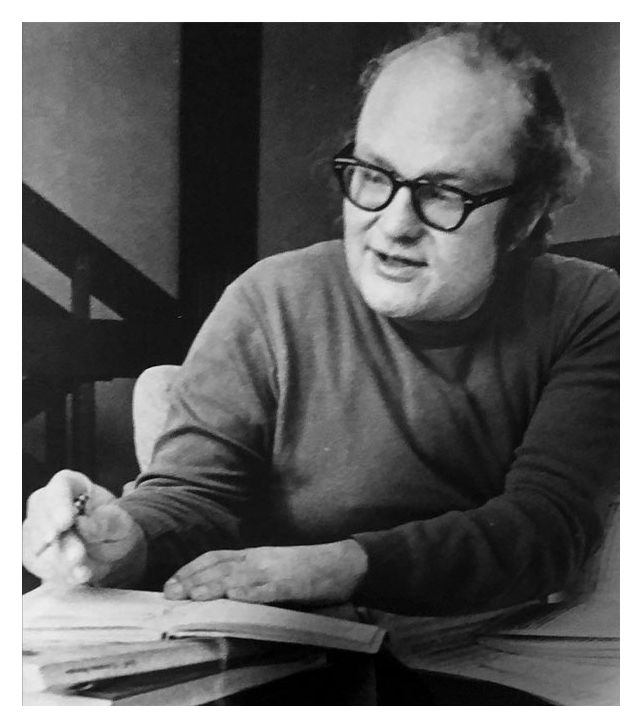

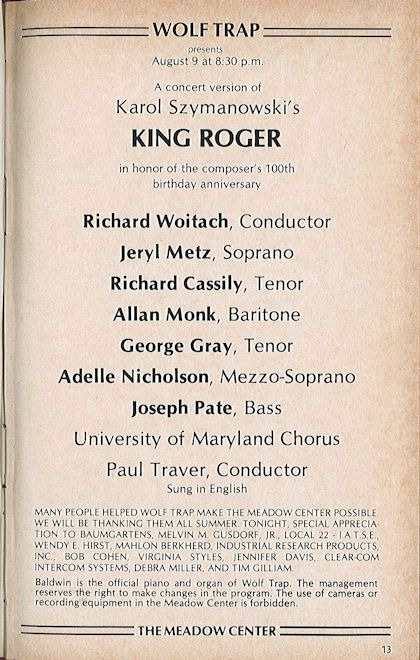

Richard Woitach, a versatile Grammy-nominated conductor and pianist whose career included nearly four decades with the Metropolitan Opera, died on October 3rd, 2020 in New York following a long illness, and had been a member of Local 802 since 1957. Maestro Woitach led over 800 performances of 88 operas, including

23 productions with the Met. He made regular appearances bringing

opera to a wider audience with the annual Met in the Parks series.

His repertoire as a conductor included over 200 orchestral works.

When he wasn’t on the podium, he was well-known for his many appearances

on the Metropolitan Opera’s radio broadcast intermission features as

a host, pianist, historian, and as an expert panel member on the Texaco

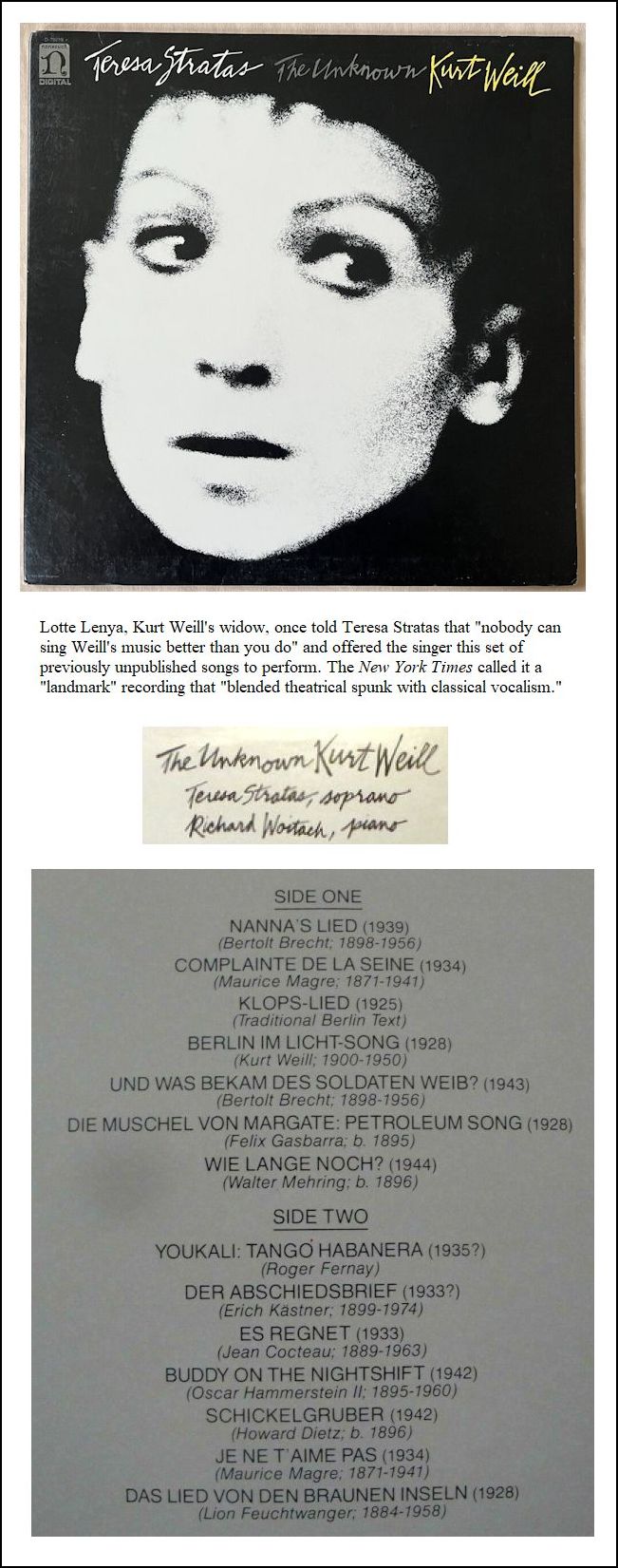

Opera Quiz. In 1981, Mr. Woitach recorded “The Unknown Kurt Weill” with

soprano Teresa Stratas, which received two Grammy nominations for best

classical album and best classical vocal soloist performance. That same

year, he accompanied the Metropolitan Opera Ballet to the White House,

where they performed Poulenc’s Babar, narrated by Werner Klemperer.

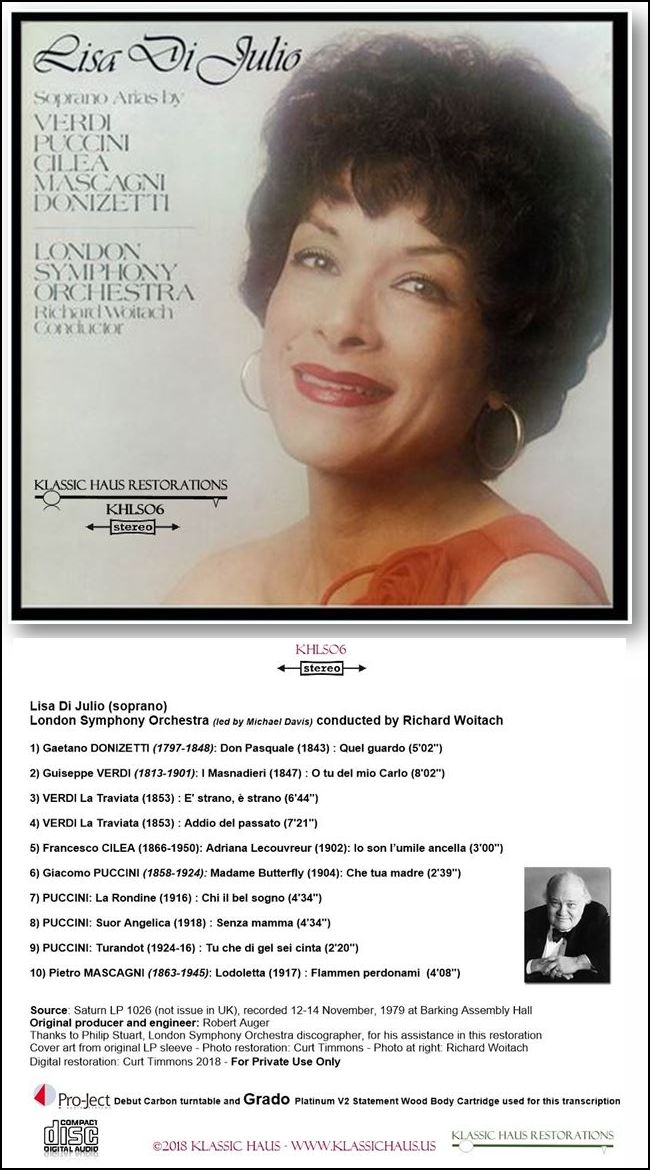

A frequent guest piano soloist with various orchestras, he also conducted

a London Symphony Orchestra recording of arias with Soprano Lisa DiJulio.

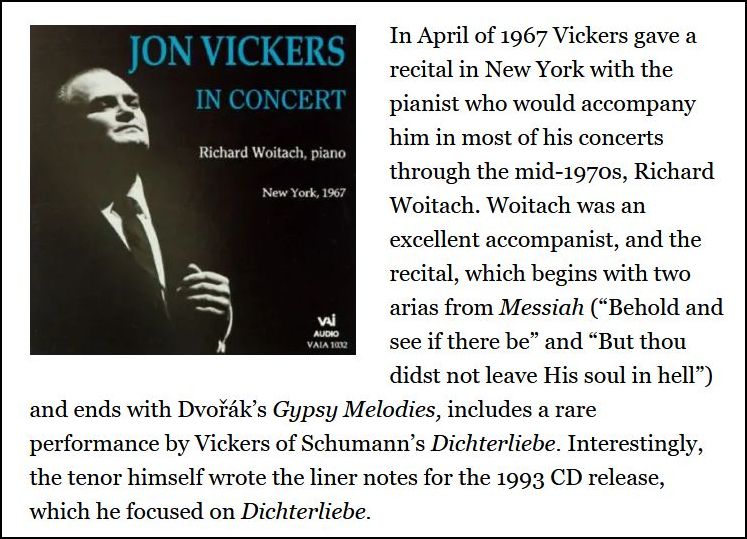

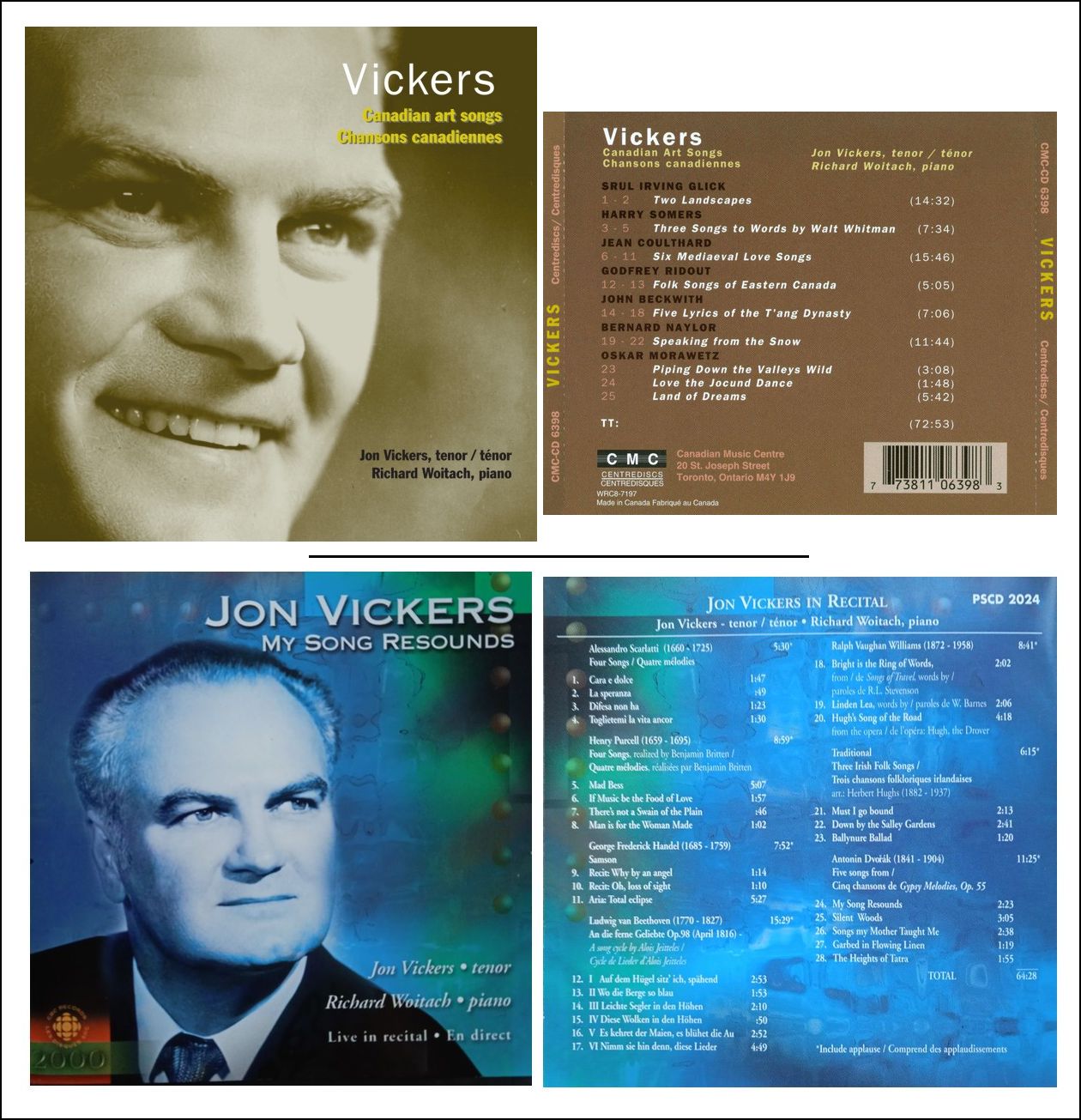

Celebrated singers with whom he played and recorded also included

Beverly Sills, Sherrill

Milnes, Anna

Moffo, Regina

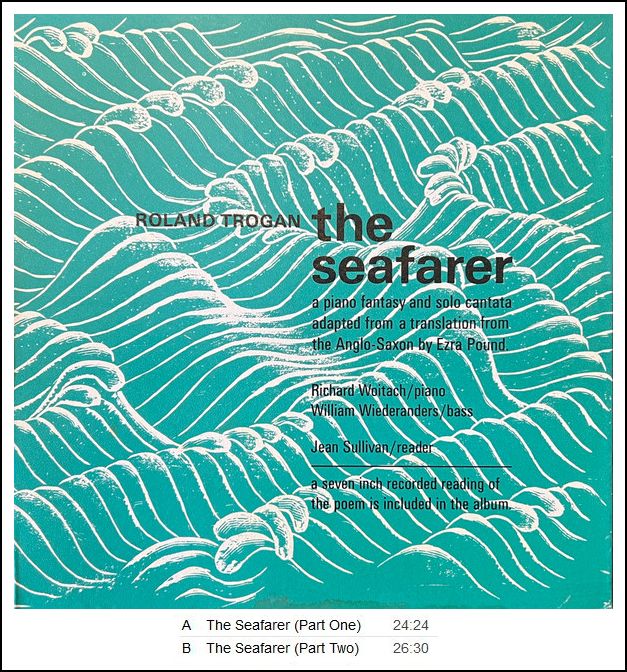

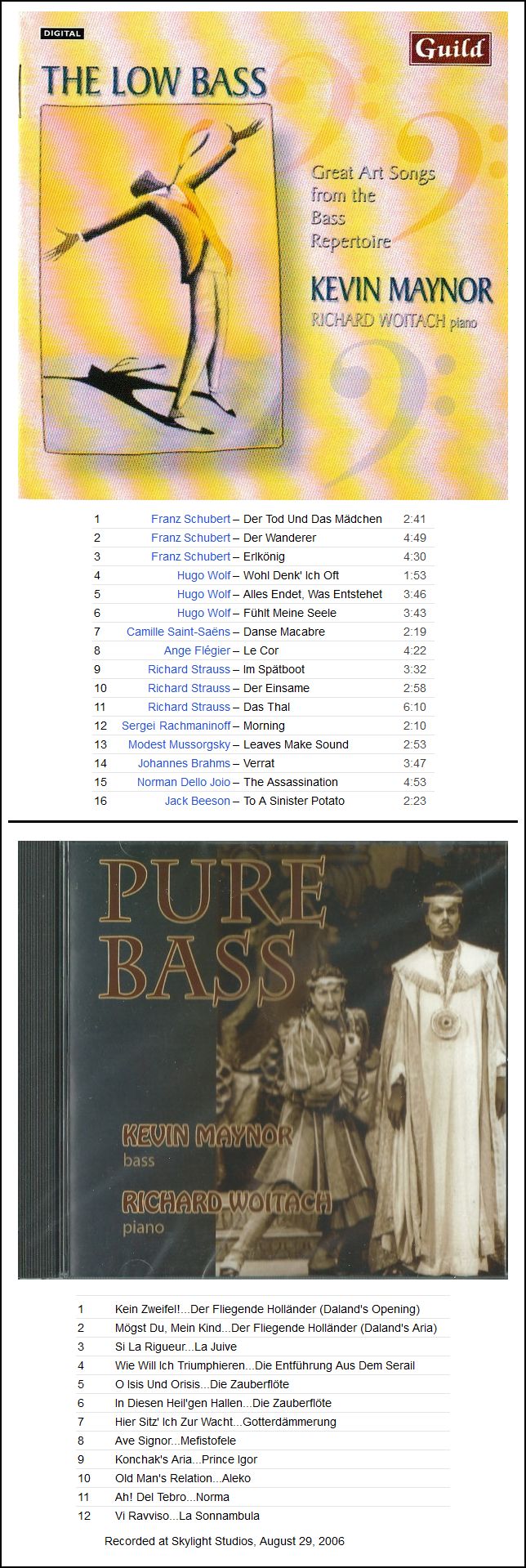

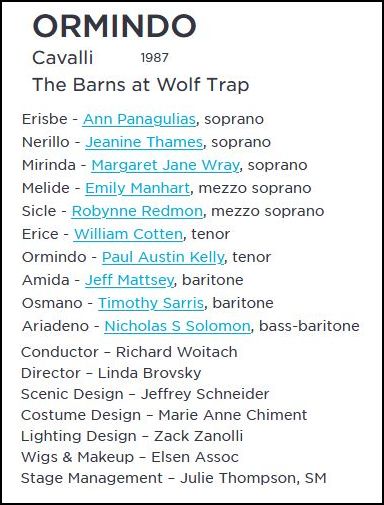

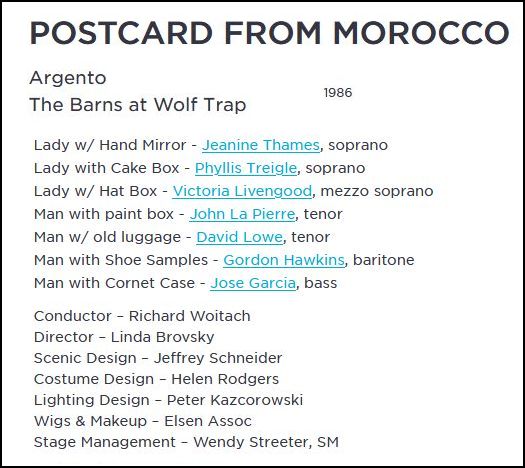

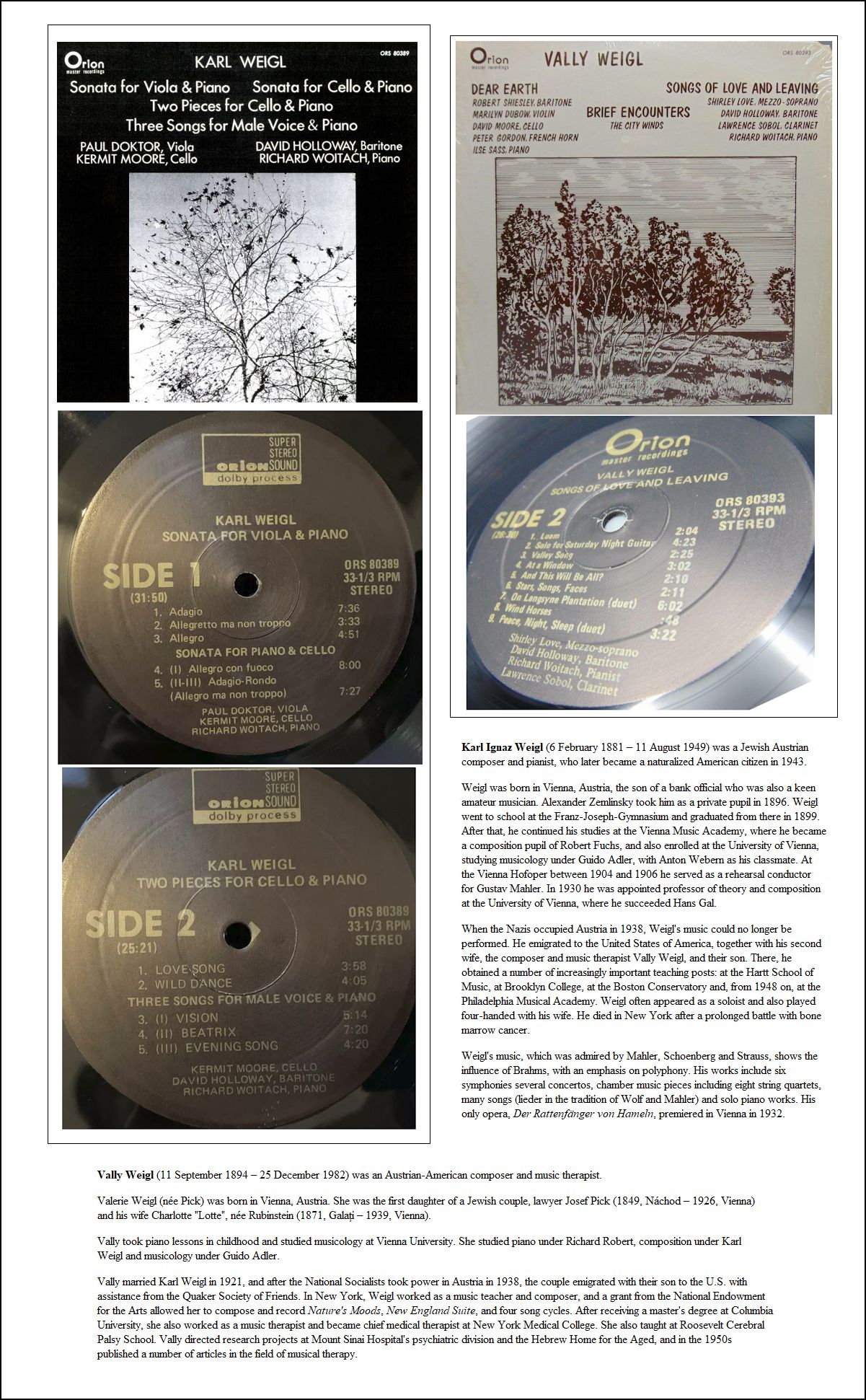

Resnik [CD re-issue shown below], and Jon Vickers. Woitach attended the Eastman School of Music, studying under Orazio Frugoni. He joined the Rochester Philharmonic as official pianist while still an undergraduate, where he appeared under the baton of his mentor Erich Leinsdorf as piano soloist, a collaboration that continued with The Boston Symphony. He toured as the piano accompanist for violinist Zino Francescatti from 1957-59, and in 1959 joined the Metropolitan Opera as a rehearsal Pianist and Conductor. Woitach made his professional operatic debut as a conductor in 1961 with the Cincinnati Opera’s production of The Barber of Seville and his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1974 conducting I Vespri Sicilliani. He served as Artistic Advisor of the Arizona Opera, Music Director of Western Opera Theatre as well as the Wolf Trap Opera Company, which he led for seven seasons. Over the years, he appeared as guest conductor with numerous companies including the San Francisco Opera Company, Opera Company of Boston, Opera Company of Philadelphia, The Vancouver International Festival, and the Milwaukee Florentine Opera. In 1990, he inaugurated the Valhalla Wagnerfest in New York State, conducting performances of Wagner’s Siegfried. Maestro Woitach was committed to bringing operatic masterpieces from his parents’ native Poland to America. In 1992, he conducted the first complete performances outside Eastern Europe of Karol Szymanowski’s Krol Roger in the original Polish, and an English production at Wolf Trap featuring Metropolitan Opera singers Alan Monk and Richard Cassily. After retiring from the Metropolitan Opera staff in 1997, Woitach served as Music Director of the Merrick Symphony, and continued to perform as pianist in recitals, and as soloist with orchestras in the New York area. In 2004, he produced and performed the world premiere of a cycle of songs for bass voice by Jack Beeson as well as a suite of selections from Twelfth Night by Donald Foster. Woitach also produced and performed piano recitals featuring works of composer friends, as well as concerts featuring music of Gustav Mahler. Woitach continued to record performances on piano after his retirement, including The Low Bass with basso Kevin Maynor (2002) [shown below-left]. A 1971 recording of Roland Trogan’s Five Nocturnes [LP shown at left] was reissued on CD in 2006. These nocturnes, which were published to coincide with the recording, were written for and dedicated to Maestro Woitach. [Another recording of a piece by Trogan is shown below-left.] A dedicated teacher and mentor throughout his career, Woitach

coached singers and taught Master Classes at San Francisco State University,

Indiana University, Academy of Vocal Arts (Philadelphia), University

of Guelph (Ontario, Canada), The Bel Canto Institute at SUNY New Paltz,

The Pittsburgh Opera, The University of Alabama, The Glimmerglass Opera

(New York), The National Association of Teachers of Singing (Toronto)

and others. He participated in programs as a member of the Institute

for Psychoanalytic Training and Research (IPTAR), which involved analyzing

the personality and music of Richard Strauss.

== Biography from the website of Local 802 AFM

|

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in a studio at WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago, on July 14, 1982. Portions were used in Opera Scene magazine three months later. A copy of the unedited audio was given to DePaul University. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.