A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

Soprano

Ruth Welting

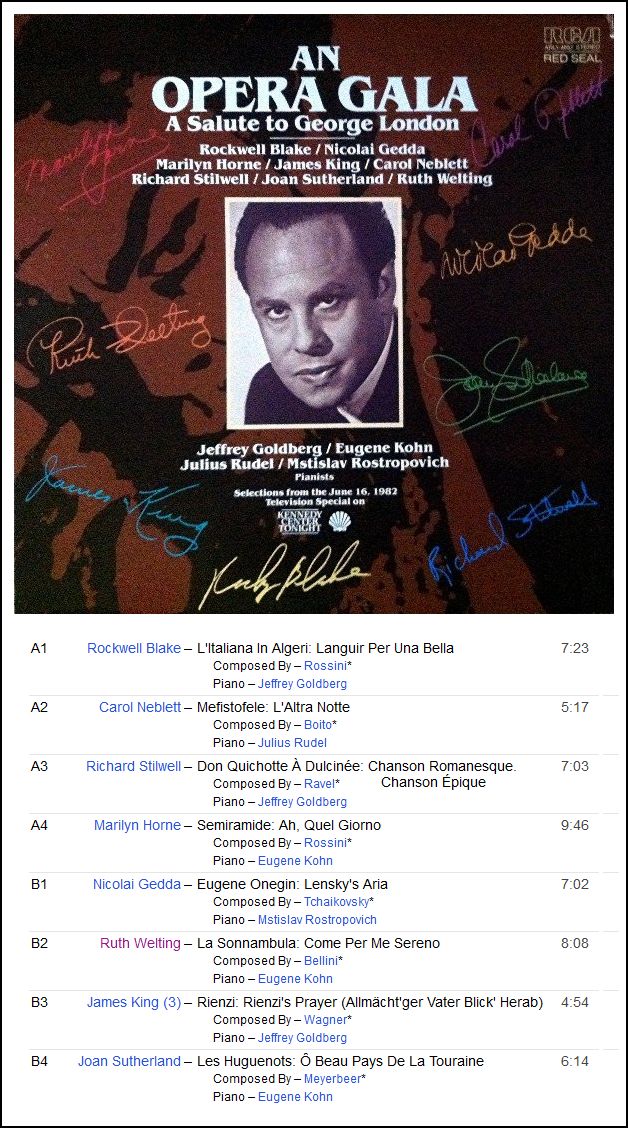

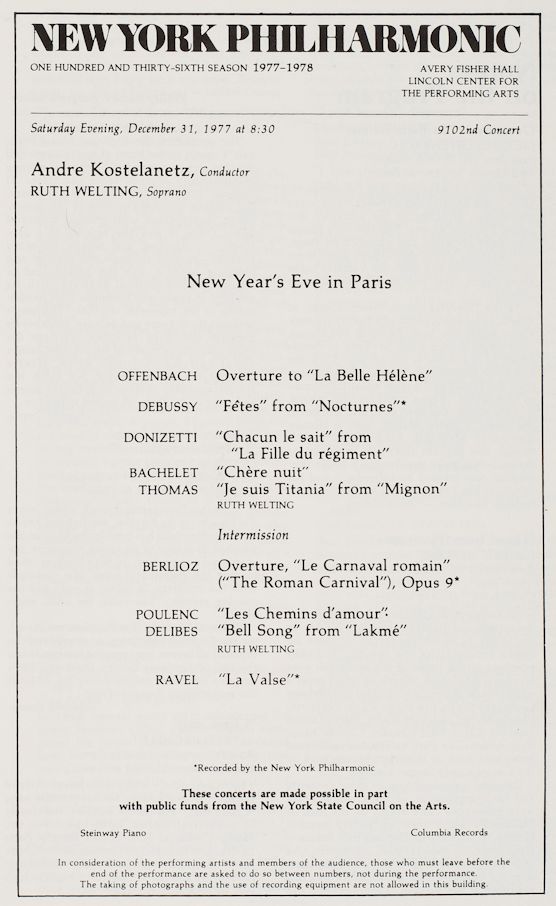

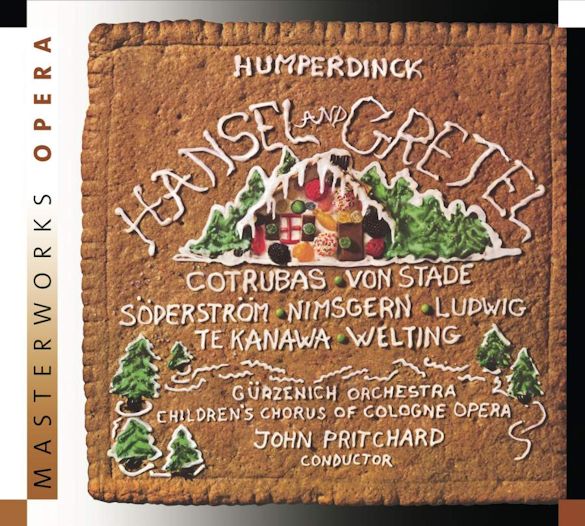

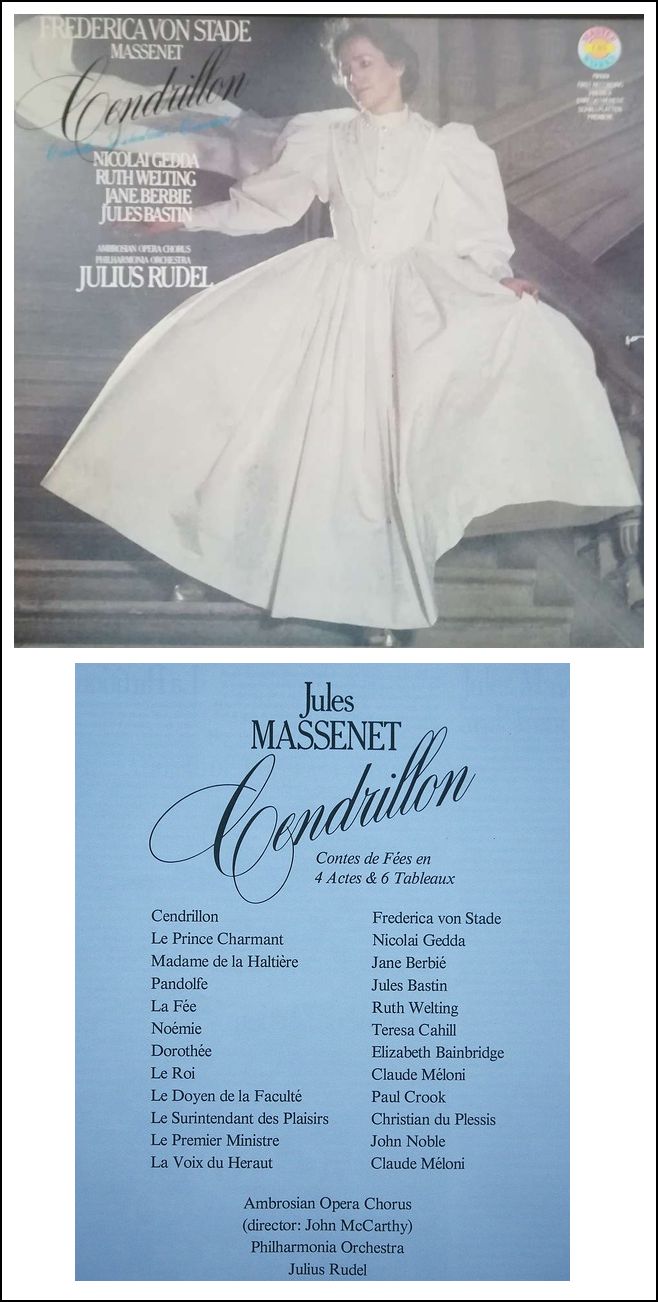

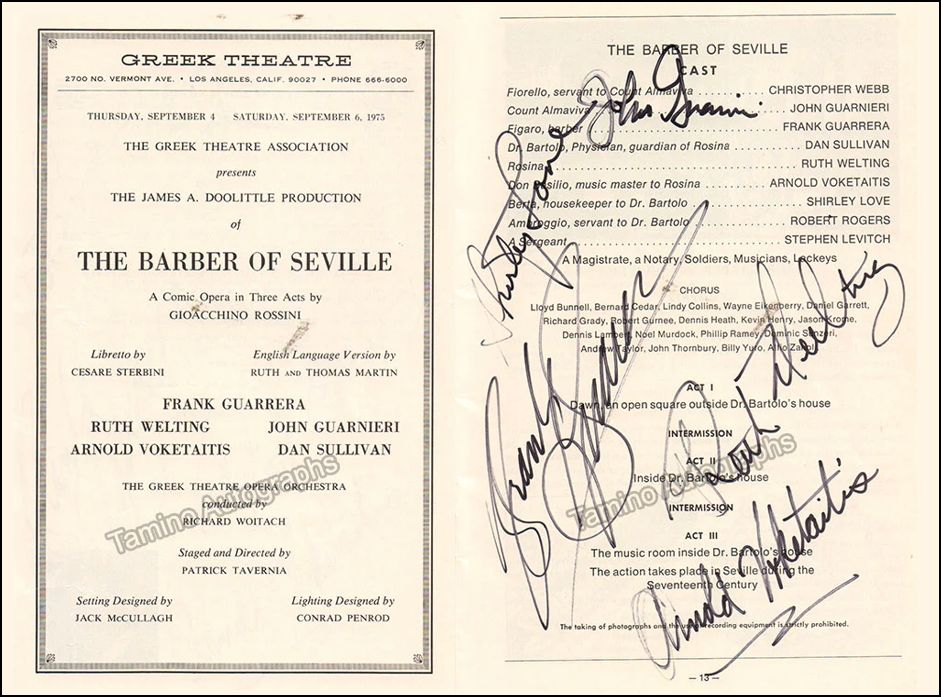

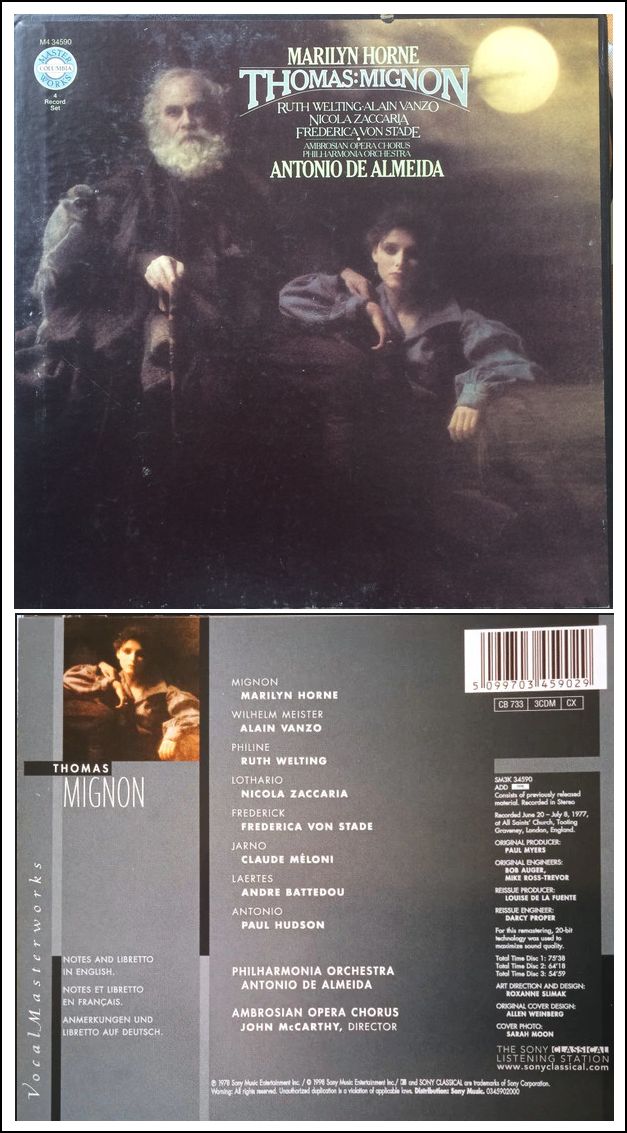

By Elizabeth Forbes The Independent Thursday 23 December 1999 [With corrections] THE AMERICAN soprano Ruth Welting dazzled her audiences with the ease of her singing in coloratura roles such as Donizetti's Lucia, Richard Strauss's Zerbinetta and Mozart's Konstanze. She produced ravishing sounds up to the F above high C, and she was also an excellent actress, who made an enchanting figure on stage. At a time when heavier voices had become fashionable in much of this repertory, she projected her light, pure-toned voice in such a way that she filled the largest auditoria, notably the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and Lyric Opera, Chicago, to the satisfaction of the listener furthest from the stage. She sang at Covent Garden, in Barcelona, Paris and Parma, but the greatest part of her career was spent in North America. Welting was born in Memphis, Tennessee. She studied in New York with Daniel Ferro, in Rome with Luigi Ricci and in Paris with Janine Reiss. At the age of 23 in 1971 she made her debut with the New York City Opera as Blonde in Mozart's Die Enfuhrung aus dem Serail. After singing Lucia at Duluth in 1973, the following year she tackled the extremely florid role of Philine in Thomas's Mignon at Boston. During the summer of 1975 she appeared at Santa Fe, singing the Nightingale and Fire in Ravel's L'Enfant et les sortileges, as well as Nannetta in Verdi's Falstaff. The same year she made her Covent Garden debut as Rosina in Il Barbiere di Siviglia. Welting made her Metropolitan Opera debut in March 1976 as Zerbinetta in Ariadne auf Naxos, one of her finest roles. She sang it during December at Covent Garden, making a much more favourable impression than she had with Rosina the year before. In Zerbinetta's great aria her shining top notes and the accuracy of her florid singing were greatly admired, as well as the sweetness of her personality. Meanwhile in 1976 she had sung at the Holland Festival as Sophie in Massenet's Werther, returning the following year as Lauretta in Puccini's Gianni Schicchi. Welting made her Chicago debut in 1976 in another of her most popular roles, Olympia the Doll in Offenbach's Les Contes d'Hoffmann. Her ability to dance as well as sing like a clockwork toy always brought forth torrents of applause. At San Francisco in 1977 she appeared as Zerbinetta, and also as Zerlina in Don Giovanni, one of her few lyric roles. Another, which she also sang at San Francisco, was Norina in Don Pasquale. Oscar in Verdi's Un ballo in maschera provided her with a congenial part at Dallas in 1978, while the following year she sang the Fairy Godmother in Massenet's Cendrillon at Ottawa, scoring a great success. Marie in Donizetti's La Fille du regiment was yet another florid role dripping with coloratura: Welting sang it at New Orleans in 1979, Dallas in 1983 and Barcelona in 1984. Returning to New Orleans in 1981 she sang the title role of Delibes' Lakmé, while in Chicago the following year she attacked the dramatic role of Konstanze in Mozart's Entfuhrung aus dem Sevail, which proved rather too heavy for her voice. There were no such complaints in Cincinnati, where in 1985 she appeared as Lucia, singing the Mad Scene in the original key of F Major. According to the soprano, "The key change gives the Mad Scene a lighter mood. The reality of madness has drawn Lucia into her own world, a childlike, beautiful one [in which] everything's just the way she wants it to be." Welting sang Ophelia in Thomas's Hamlet (one of her last new roles) at Chicago in 1990, with Sherrill Milnes in the title role. The following year she sang Zerbinetta in Madrid; in 1992 Marie at Portland, Oregon; and in 1993 she gave her last performance at the Metropolitan as Queen of Night in Die Zauberflote. For more than 20 years she had sung a very taxing repertory and her voice was beginning to show the wear and tear. At her best, as Zerlina, as Marie, as Olympia and as Lucia, she was unsurpassed. She spent the years 1994-98 at Syracuse University studying government. After graduating there she attended the Maxwell School of Government. Elizabeth Forbes Ruth Welting, opera singer: born Memphis, Tennessee 1 May 1948; died Asheville, North Carolina 16 December 1999. |

This interview was recorded at her apartment in Chicago

on October 20, 1981. Sections were used (along with

recordings) on WNIB in 1989, 1994, and again in 1999. It

was transcribed and published in Opera

Scene Magazine in May of 1982. The transcript was re-edited

and posted on this website in 2013. Additional photos and links were

added in 2024.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.