|

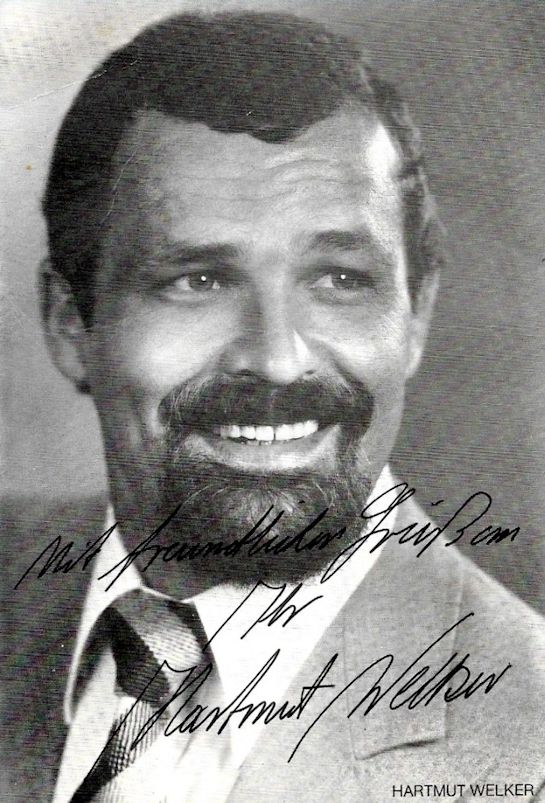

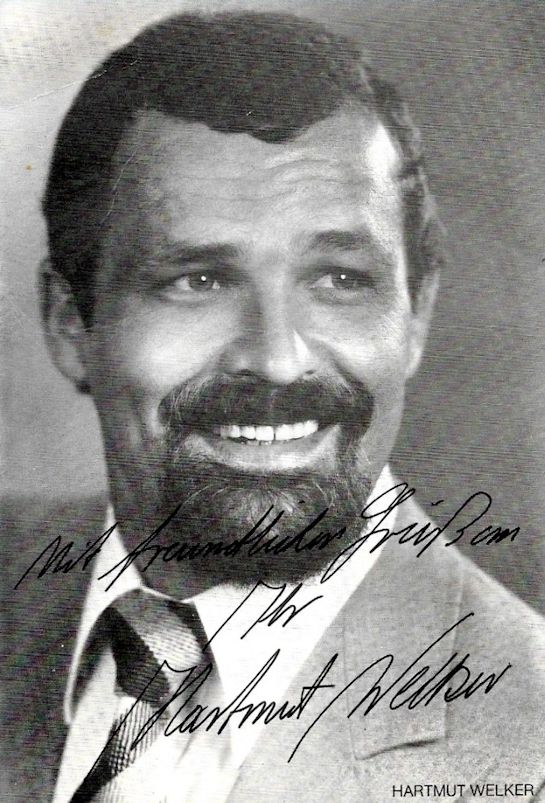

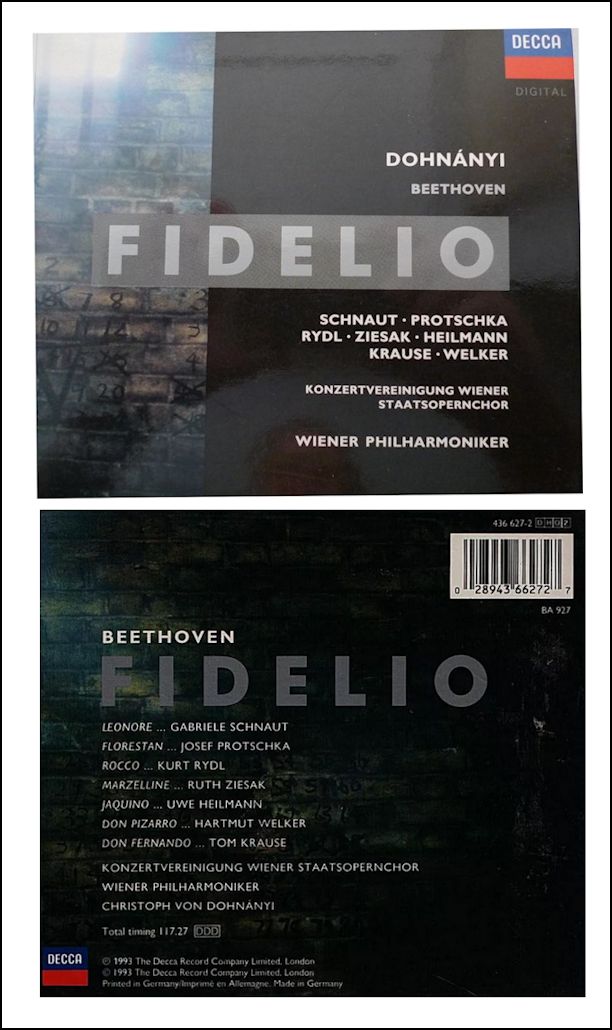

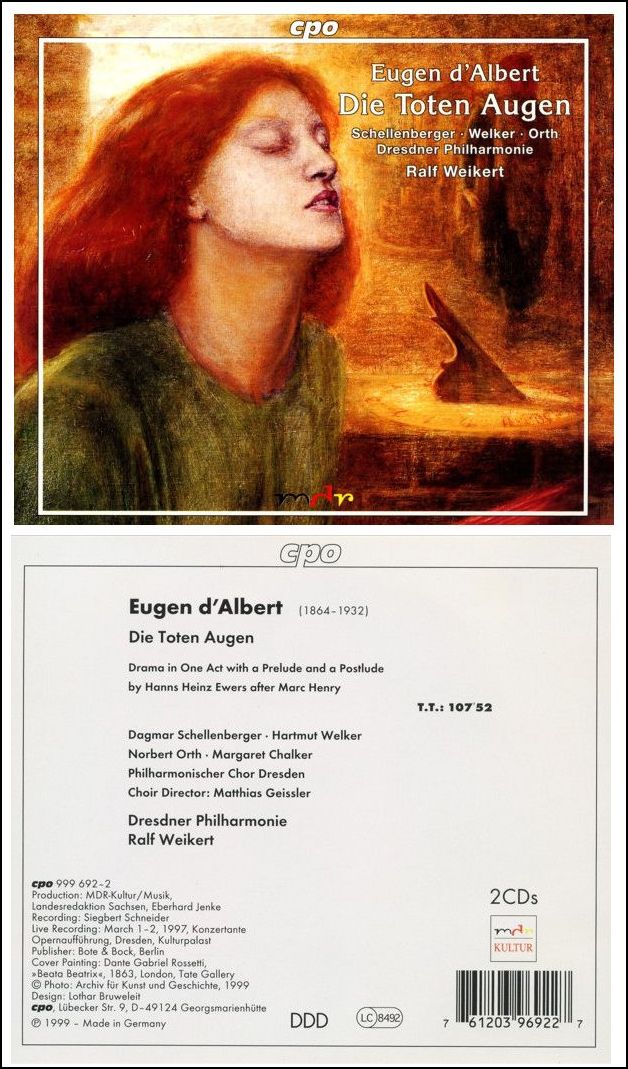

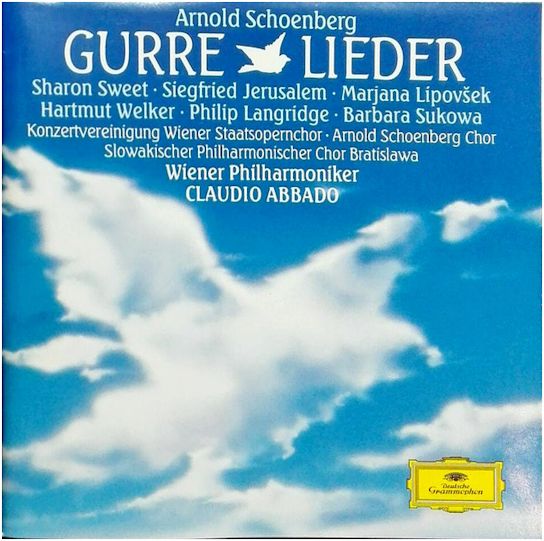

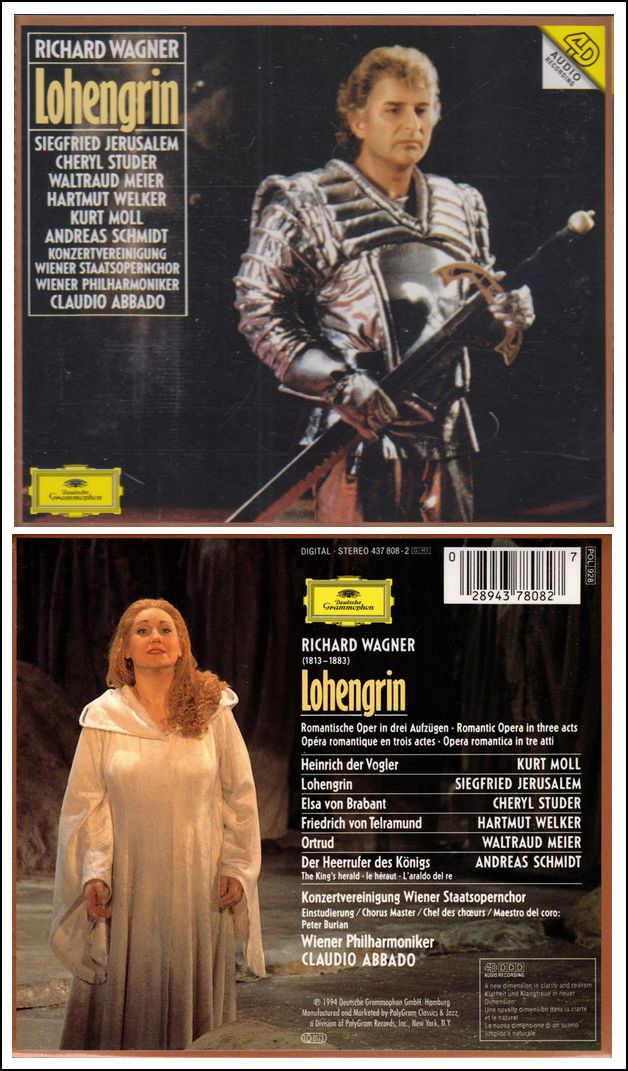

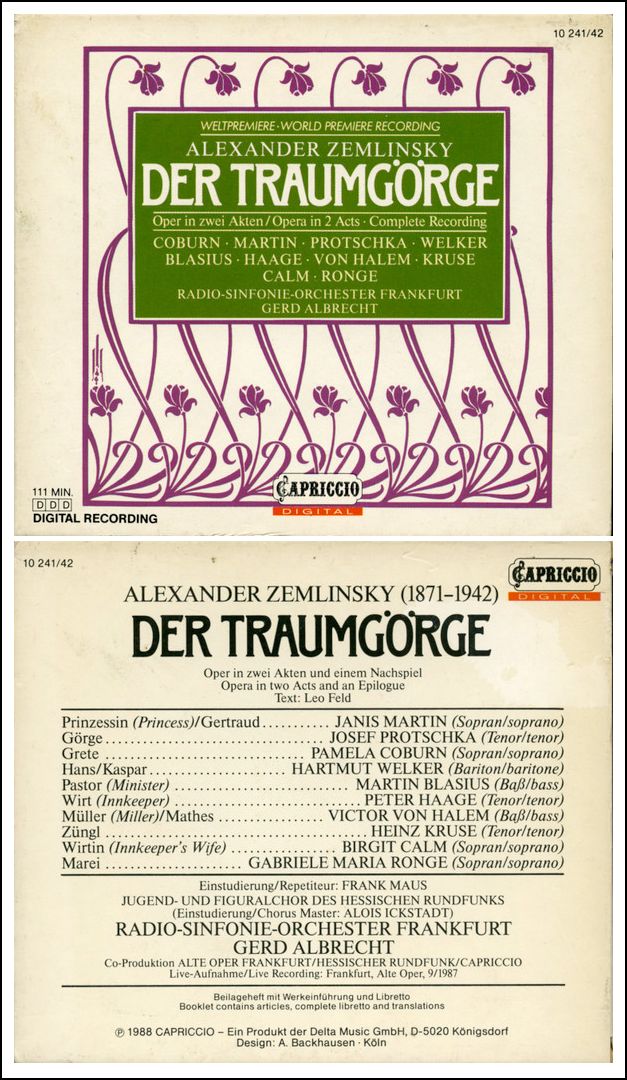

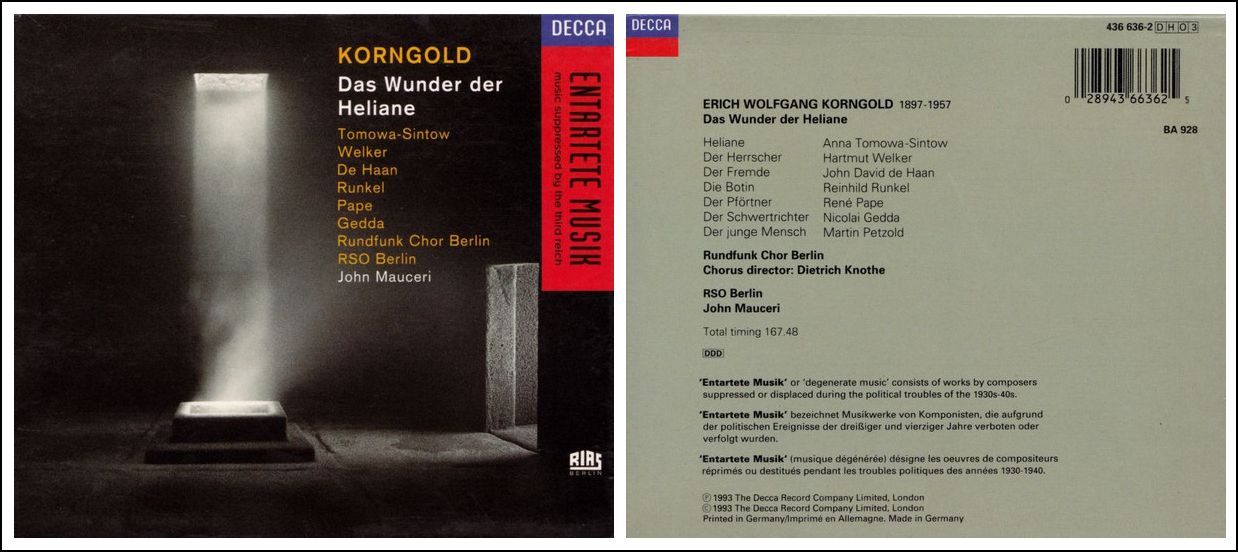

Hartmut Welker, born October 27, 1941 in Velbert, is a German operatic bass-baritone. Before he decided to study singing, he had learned and practiced the profession of toolmaker. At the age of 28, he began studying singing at the Hochschule für Musik und Tanz Köln with Else Bischof. He made his stage debut in 1974 at the Theater Aachen in the role of Monterone in Verdi's Rigoletto, stepping in for an ill singer. From 1975 to 1977, he was engaged as a chorus singer at the Aachen Opera House, where he also performed small solo parts. He made his official debut there in 1977 as Renato in Verdi's Un ballo in maschera. He worked there until 1980, and was subsequently engaged for three years at the Badisches Staatstheater Karlsruhe, to which he later belonged as a permanent guest. During these years he had numerous guest appearances in major opera houses around the world, such as the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, the Royal Opera House Covent Garden in London, the Opéra Bastille in Paris, the Vienna State Opera, Berlin State Opera and Hamburg State Opera, as well as the Bayreuth Festival, the Salzburg Festival, the Bregenz Festival and the Edinburgh Festival. Welker was a member of the Hamburgische Staatsoper since 1982, the Vienna State Opera since 1985 and the Deutsche Oper Berlin since 1987. He also has performed in concerts and television productions. Hartmut Welker is the father of the director Sebastian Welker. |

See my interviews with Anna Tomowa-Sintow, and John Mauceri

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 20, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1995. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to Ann Vickstrom of Lyric Opera of Chicago for translating. My thanks also to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.