Composer Hayden Wayne

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Composer Hayden Wayne

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Every once in awhile, you get the chance to meet someone who is totally and completely in synch with a different time. Like stepping back into the late '60s and '70s, to meet and speak with Hayden Wayne is a journey not only to the past, but also to the far future. His vision combines sensibilities of his own background with the latest advances in science and technology.

For more info about him, including a full biography and a large gallery of photos, visit his website .

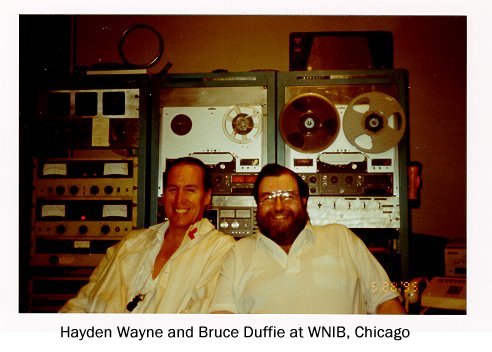

It was the 50th anniversary of D-Day, and we had been at a performance

of the Chicago Sinfonietta conducted by Paul Freeman. Later,

we met at the WNIB studios and had this conversation . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You’re both a composer and a performer. How do you divide your time?

Hayden Wayne: Actually I've just had a very intense three and a half years of writing over 2000 pages of score.

BD: Which would account for how many works, roughly?

HW: There’s a full ballet, two symphonies for large orchestra, a 100-minute one-act opera, the orchestrations to a street opera...

BD: Are these things you just had to write, or are they commissioned?

HW: I wrote them because I had to write them. But, also, dealing in today’s insanity, it’s a lot easier to say, “Here’s the piece,” when most people are very well practiced at the art of the “B.S.”

BD: But are you looking forward to the day when someone will come to you and say, “Write me a piece”?

HW: Oh, absolutely! As what has recently happened with this cantata I wrote, called In Memoriam: a celebration, which had its world premiere at St. John the Divine in November. In fact I just had a meeting today, with the people in Skokie (Illinois), for a performance May 28th. And the same piece will be in the Old Testament Festival in Prague. This is all in ‘95 in Wodz, in Poland, and possibly again at St. John’s at the end of the year. So the one piece will really get a lot of play, which I’m very proud of. I’m always looking for commissions. Any of you D’Medici’s out there, please?

BD: [Laughs] Well, if you get the commission, how do you decide to do it or turn it down?

HW: It’s funny, I’m not really like Bette Davis where I’ve really learned how to say no, unless something is so blatantly wrong because I love any excuse to write.

BD: Write a concerto for piccolo, ocarina, and tuba?

HW: Could be a lot of fun. [Laughter]

BD: Since you’re not dealing with commissions at the moment, let’s talk about the other way. How do you decide which piece you’re going to work on? Do you decide you’re going to write a symphony or write a cantata or...?

HW: Well, actually, it’s a good question. I had written

my first symphony, the Symphony of Friends, which is about four people

in my life. It’s kind of like a collection of mini-tone poems, but

not in the big sweeping sense of what Africa is as a tone poem, where

you visualize the topography and all these moods; these are really portraits

of people. After that first one was done, I was thinking, “My God,

what next?” And this flip idea – at the moment, it was flip idea –

kept popping in my head, a reggae symphony, and I started laughing.

All of a sudden I said, “Wait a second, what a great exploitive title if

somebody could really dig in and write the thing!” And I thought, “Well,

if I was to seriously take this on, what would I have to do; gleaning all

the figures and the motives so to develop them into symphonic form.”

The more I thought about it, the more it started to really grab me.

What happened was, REGGAE led to HEAVY METAL, which led to FUNK, which is

the trilogy. Being that they are indigenous black folk idioms, when

I completed that thinking, “My God, what’s next?” Well I had to go

to my roots, and that was Africa. It's ALL our roots. That was

an amazing experience because in the process of doing research for that,

hundreds and hundreds of cassettes dealing with the entire continent (it’s

an amazingly diverse continent), and then putting it together the story from

an Euro-ethnistic point of view. And as everyone knows, African

ethnicity mixing with Euro-ethnicity gave America its original, jazz – which

begot rhythm and blues, which begot rock-n-roll, and then its sub delineations

– i.e., reggae, funk, and, bless your hearts, they gave me my wherewithal

to write my symphonies. It’s not a new discovery. I mean, my God, Dvorak

came here and he said, “America, wake up, it’s right here in your black community

and your Indian community.” And what’s exciting about that is that the

piece will be performed by the State Philharmonic of Brno. They are

going to do the world premiere of the Fourth Symphony in February of

‘95 and record it. I’m very flattered by what has happened. They

are doing an anthology of 300 years of music culminating with, I guess, as

if Dvorak reaches into America and me reaching back. That I was chosen

is staggeringly flattering. I’m very pleased. It’s a wonderful orchestra.

It’s really very exciting.

HW: Well, actually, it’s a good question. I had written

my first symphony, the Symphony of Friends, which is about four people

in my life. It’s kind of like a collection of mini-tone poems, but

not in the big sweeping sense of what Africa is as a tone poem, where

you visualize the topography and all these moods; these are really portraits

of people. After that first one was done, I was thinking, “My God,

what next?” And this flip idea – at the moment, it was flip idea –

kept popping in my head, a reggae symphony, and I started laughing.

All of a sudden I said, “Wait a second, what a great exploitive title if

somebody could really dig in and write the thing!” And I thought, “Well,

if I was to seriously take this on, what would I have to do; gleaning all

the figures and the motives so to develop them into symphonic form.”

The more I thought about it, the more it started to really grab me.

What happened was, REGGAE led to HEAVY METAL, which led to FUNK, which is

the trilogy. Being that they are indigenous black folk idioms, when

I completed that thinking, “My God, what’s next?” Well I had to go

to my roots, and that was Africa. It's ALL our roots. That was

an amazing experience because in the process of doing research for that,

hundreds and hundreds of cassettes dealing with the entire continent (it’s

an amazingly diverse continent), and then putting it together the story from

an Euro-ethnistic point of view. And as everyone knows, African

ethnicity mixing with Euro-ethnicity gave America its original, jazz – which

begot rhythm and blues, which begot rock-n-roll, and then its sub delineations

– i.e., reggae, funk, and, bless your hearts, they gave me my wherewithal

to write my symphonies. It’s not a new discovery. I mean, my God, Dvorak

came here and he said, “America, wake up, it’s right here in your black community

and your Indian community.” And what’s exciting about that is that the

piece will be performed by the State Philharmonic of Brno. They are

going to do the world premiere of the Fourth Symphony in February of

‘95 and record it. I’m very flattered by what has happened. They

are doing an anthology of 300 years of music culminating with, I guess, as

if Dvorak reaches into America and me reaching back. That I was chosen

is staggeringly flattering. I’m very pleased. It’s a wonderful orchestra.

It’s really very exciting.

BD: On just a technical note, how does it wind up that the Fifth Symphony is done and recorded before the world premiere of the Fourth Symphony?

HW: What happened was we went through the work and they decided to do the 4th, and we did a cold reading. Then they decided, “Okay, let’s do the 5th”. Ultimately, I would like for all my works recorded...

BD: I guess the thing that interests me is why would you write a 5th symphony without having heard the performance of the 4th?

HW: Well, let me put it to you this way, beggars can’t be choosers. Whatever the mood is of the Boards and conductors and the orchestras, it’s hard enough to find an orchestra that will play five minutes of your music for anything over 15 musicians. Here these pieces are for 85-100 musicians and they’re almost 50 minutes in length. It’s funny, because being fair, to try to understand this, when you look at a European orchestra dealing with truly American idioms, it’s a stretch sometimes. What happened is they tested the waters with that, and when they looked at Africa, they felt that Africa somehow was an easier tackle for a first release, but they were so intrigued by Funk that that’s what they wanted to do the world premiere as part of this big season of theirs, and subsequently recorded. They are so hell-bent on really nailing it, they have given me so much remarkable time with rehearsal, it’s like I said, it’s very flattering!

BD: Now, you use the term, funk. What is your musical background? I know that you came from a more popular idiom in terms of music, so how did you get into the classical idiom?

HW: I’m 45, so rock-n-roll was born into me as a folk idiom. I was 3 when Bill Haley and the Comets came out. I was 5 when the Grandfather of rock-n-roll, Chuck Berry, the Master, came out. Then, of course, Elvis, and subsequently the ride took off, and the Beatles, and Peter Townsend, and all these brilliant moments right through the 60s with the Renaissance of all that...

BD: This is the stuff you listened to and enjoyed and imitated?

HW: Yes, and even performed, because I’m a dyed-in-the-wool rocker. But, to really add the true focus on my education, my father was in the society end of music where you literally could not request a tune he couldn’t play. So you can imagine that eclectic group of the hit parade. All the publishers would be sending him the latest scores hoping that he would play something as the shows were out on the road working their way into New York, so I had that. He was very neurotic about me getting my education - i.e., classical, and I was a kid – rock-n-roll. So one day would be 1860, one day would be 1960, one day it would be 2060. Rather than being a total free-for-all/chaos, somehow I was developing a voice within all this mish-mosh, and it was quite extraordinary to see direct parallels. Like, you know, Beethoven, for instance. I tongue-in-cheek say was doing Peter Townsend licks of the Who 150 years before the Who, and then we had our punk, Igor Stravinsky. You know? There are great parallels here – the acid period, the drug period, Wagner, and chromaticism. Or you could say you get even further – you get into spikier camps – the Schoenberg and Webern, and on and on. There are direct parallels, there’s no question. The big difference here, which makes it in one respect very exciting and in another respect very scary, is that yesterday, as it were, 100 years ago, there was one language. Even though there was always folk music, the big language was the classical voice. Today, ironically, the big voice is the folk voice because of technology. Anybody can get printed onto tape. Anybody can pick up some kind of instrument, whatever that is, whether it’s electronic or a guitar, and print well and sizable enough because of the electronic medium, to have worth. Ironically, a 4-piece band can sound bigger than 100-piece orchestra.

BD: Is that good or bad or just there?

HW: Well I can’t be a snob about it, and I don’t mean to be that ambiguous about it. I’m a firm believer that anything that is honest and truly well executed deserves a moment in the sun. But the bottom line is, I think we have reached the point now that so many things have become caricatures of themselves and, especially in the minimalist sense of what is existing in folk music, that we’re finding ourselves getting into more social-political regurgitations – i.e., of rock-n-roll. I tie this into classical directly because all the great masters dealt with folk music, so we have to examine folk music here. A lot of my colleagues have not drawn on this, and I feel that they have lost their audiences because of that. That’s another thing I will get into. But you look into how we had, as I said before, this renaissance in the 60s, – i.e., the Beatles, the Who, Focus, and all these cross-over groups. It was getting more and more complex. The beginnings of jazz starting to infiltrate rock-n-roll. Then all this fusion that went back out, and we’ve had a resurgence of what we now call classical jazz. That’s another camp. What happened, interestingly enough, in the 70s was punk nihilism came in. With that one just went, boom, denial! It denied everything we had evolved to and went back, because of demand of what I feel was pubescent necessity, which is really idiomatically, what rock-n-roll is. The difference is, however, in the 50s, where pubescent energy, youth demanding its own recognition. It finally got to a point where we were sexual, because rock-n-roll and sex is same. It’s metaphorically one for the other. I don’t mean to be crass saying this, but a person would pick up, metaphorically, a guitar to get laid! Today a person picks up a guitar to make a million dollars. To me that’s a broad difference. Even though it’s naive, i.e., folk, once you’ve evolved and gone through a renaissance, if you deny what you’ve evolved to, to go back to your pubescent roots, it’s a lie. So it becomes oxymoronic. That’s why I consider, from Public Image Limited onto today, we’ve had a social political commentary, as opposed to a pubescent necessity of expression. Me? I couldn’t deny my roots. Granted I was classically trained, but my folk roots were with me in all the rock-n-roll bands I had played and toured with. The obvious route to go was into classical music for me. A great many of my colleagues went into jazz, and we see now these resurgences, thank God, and these high, high camps of music. The scary part about all of this is many of my colleagues, the elder guard, have been so ruthlessly arrogant, to the point of just thumbing their noses at the audience so they could pat themselves with their sycophant mentalities, and say, “Isn’t this great! Doesn’t this look great on paper!”, and have for 40 years alienated audiences. Granted this is just my opinion, and I could be crucified for what I’m about to say: I personally feel that serial composition was an experiment taken too seriously. I don’t even think Schoenberg would have expected the result of what had happened in the subsequent 40 years where, granted, there are a handful of truly wonderful mystical pieces, but primarily it all sounds like it was written by the same bloody composer.

BD: So it’s really a blind alley? You should look into it, but then get out and go back on the main street?

HW: Well how long do you kick the horse before you realize the

horse is dead? If a lot of the elder guard are saying, "This man is

crazy”, look at your dying audience. I’m going to prove it scientifically

right now: A rave sale in records is 5-8000 units in classical music.

It even puts us on the charts. In pop or rock-n-roll, if I didn’t sell

5-8000 units in my own neighborhood, and if I lived in an apartment complex

in my own building, I’d be laughed out of the business. Granted, I’m

getting a little fringy and a little exaggerated, but the 5-8000 units is

the gospel – that’s a rave in classical and in jazz! That’s very sad,

because those are high forms. The big scary thing is now, with the

accountant-driven mentality of this corporate monopoly GNP orientation, they

say, “Well”. . . – you know, they play hardball, and rightfully so; that’s

their game plan like music is my game plan and you have yours – but they

get into this thing of saying “Well, you know, the audience doesn’t buy that!”

I say, “But there’s an audience for...” “No, they won’t buy that!” “Why don’t

you give the audience a chance to decide yes or no.” You know, that

famous expression, if a tree falls in a forest and if you’re not there, did

it fall? I take it further, I say, “Is there a forest?” because this

is what they’re doing. They’re doing broad cross-cuts!” We look

at our generations and we look at the devolution in folk music to the raw

state where, even in rap, which is a very important folk expression for people

who have to express, but, if you look at the syntax of language, that has

even disintegrated. Imagine e e cummings or Ferlingetti to rap.

Very plausible, isn’t it? It would be quite exciting. I mean,

if you can get the copyright clearance, it would be worthwhile to go into

the studio and you’d make it worthwhile. But rap is rap. I’m

into more complex musical things, and here I am.

HW: Well how long do you kick the horse before you realize the

horse is dead? If a lot of the elder guard are saying, "This man is

crazy”, look at your dying audience. I’m going to prove it scientifically

right now: A rave sale in records is 5-8000 units in classical music.

It even puts us on the charts. In pop or rock-n-roll, if I didn’t sell

5-8000 units in my own neighborhood, and if I lived in an apartment complex

in my own building, I’d be laughed out of the business. Granted, I’m

getting a little fringy and a little exaggerated, but the 5-8000 units is

the gospel – that’s a rave in classical and in jazz! That’s very sad,

because those are high forms. The big scary thing is now, with the

accountant-driven mentality of this corporate monopoly GNP orientation, they

say, “Well”. . . – you know, they play hardball, and rightfully so; that’s

their game plan like music is my game plan and you have yours – but they

get into this thing of saying “Well, you know, the audience doesn’t buy that!”

I say, “But there’s an audience for...” “No, they won’t buy that!” “Why don’t

you give the audience a chance to decide yes or no.” You know, that

famous expression, if a tree falls in a forest and if you’re not there, did

it fall? I take it further, I say, “Is there a forest?” because this

is what they’re doing. They’re doing broad cross-cuts!” We look

at our generations and we look at the devolution in folk music to the raw

state where, even in rap, which is a very important folk expression for people

who have to express, but, if you look at the syntax of language, that has

even disintegrated. Imagine e e cummings or Ferlingetti to rap.

Very plausible, isn’t it? It would be quite exciting. I mean,

if you can get the copyright clearance, it would be worthwhile to go into

the studio and you’d make it worthwhile. But rap is rap. I’m

into more complex musical things, and here I am.

BD: Are you sure that you’re not interested in things that are a little too complex and that are just hard to listen to in a different way than the atonal school was in its way?

HW: Yes and no. The pianist Rubinstein, said, “I don’t play from the head or the heart, I play from the gut.” I feel that’s the immediacy and the accessibility. You know, funny, “accessibility” is a dirty word to my elder guard. They feel that you have to be so erudite and so remote and stretch. True, you do, but, my God, Beethoven does that, and yet Beethoven’s accessible at the same time!

BD: But you in no way have sold out?

HW: Oh God, no. I’d cut my throat first.

BD: You’re still saying in your music what you want to say in it?

HW: Absolutely.

BD: And how you want to say it?

HW: As we were just saying, what, ten minutes ago about this 3 ½-year purge (where I wrote 2000 pages of fully orchestrated score), I wake up every day, as it were – I’m saying this metaphorically – in terror about my own worth, but I’ve got the Grandfathers before me. It’s every day I know whatever I write I’m immediately going to be compared to whoever has written anything before me, and there’s a wonderful library of BRILLIANCE out there! Have I spun my wheels for nothing? There’s a Zen aspect too. When I expire if I’ve lived my life as a composer, haven’t I succeeded anyway? Well, yes, of course. But there’s the ego which drives us, not the vanity. Vanity thinks I’m too good, I don’t have to write. It’s the ego that says that I MUST write. I have other colleagues who get freaked out about the political mumbo jumbo that’s happening with grants and who’s getting them, and the right people are not getting them, etc.. Then somebody said something to me, “This is great; let the NEA fail, let this one fail, let that one fail.” I said, “What, are you crazy? They’re supporting orchestras.” He said, “No, no, you don’t understand: There are all these people claiming that they’re artists, but when the money goes, they’ll find other alternatives, they’ll find other jobs, they’ll go back to doing other things. But all of us that have to be artists, we still will be.” Now, you know, me saying that and pointing to myself, it can come off very arrogant, but I recognize his frustration when he said this to me. I have no choice for myself. I get up and I write and I’m driven. It’s a maniacal drive!

BD: So, if necessary, you would be in the starving garret.

HW: Oh yes! Depending on who supports me, I vacillate

that sine wave in and out and in and out. The most important thing

for me is that, interestingly enough, thank God I have never been dry.

I’ve always been fertile. The difficult thing is finding that space

to just disappear and stop time. Africa was written in five

months. My wife had to go back to the Czech Republic to take care of

some business. I love my wife dearly – it was like, we’re really integrated

– and, not to go crazy, all of a sudden this purge started. The next

thing I know I hadn’t slept for four days and I had written the 5th movement

in those four days! Now that’s insanity! It happens, but if you

keep doing that you can die. It’s one of these things. That was

a gusher that came out and I felt wonderful about that. Then there

have been these horrendous times where it’s worse than pulling teeth, and

you fight it, and its just for the shear ego of discipline: “Dammit,

I am going to finish this!” And you hate it! You hate it!

You curse yourself and you’re throwing tantrums in your mind, paper’s falling

here and pencils are breaking there, and somehow it gets finished. Then

you throw it in the drawer totally unrequited and you forget about it.

Your life goes on and you kind of heal, you know? With the help of

psychotherapy you get through it. Lo and behold, 10 months later you

stumble across this piece, “My God, this is incredible!” You discover

it’s a window so far ahead of yourself and you know you didn’t write it,

because you consciously fought it every note of the way. I cannot explain

that other than divine intervention. That’s happened to me several

times. Now I don’t even question it. I just know I’m writing

something and I say to myself, “Oh man, this is like, uh, yeah, push,

push”. I think of one of my great teachers, Larry Wilcox, may he rest

in peace. He taught me how to listen. Technically, he was one

of my orchestration teachers. But, truly, he taught me how to listen,

and it was quite fascinating. He would say, “Get this particular score,

this edition. Don’t open it, I don’t want you to look at the score;

just pick it up and get it ready. Get this recording. I want

you to put it on, then clean your house, go grocery shopping or something,

just put it on wrap-around, let it play all day long.” In essence he

said, “I don’t want you sitting in front of the stereo; just put it on and

do what you do. At the end of the week I want you to sit down and listen

to it.” And I realized what he was doing subsequently. Because

the piece was written subliminally, it didn’t start necessarily at A and

went to Z. It may have started at P and then went to K and then went

to O and then somehow...

HW: Oh yes! Depending on who supports me, I vacillate

that sine wave in and out and in and out. The most important thing

for me is that, interestingly enough, thank God I have never been dry.

I’ve always been fertile. The difficult thing is finding that space

to just disappear and stop time. Africa was written in five

months. My wife had to go back to the Czech Republic to take care of

some business. I love my wife dearly – it was like, we’re really integrated

– and, not to go crazy, all of a sudden this purge started. The next

thing I know I hadn’t slept for four days and I had written the 5th movement

in those four days! Now that’s insanity! It happens, but if you

keep doing that you can die. It’s one of these things. That was

a gusher that came out and I felt wonderful about that. Then there

have been these horrendous times where it’s worse than pulling teeth, and

you fight it, and its just for the shear ego of discipline: “Dammit,

I am going to finish this!” And you hate it! You hate it!

You curse yourself and you’re throwing tantrums in your mind, paper’s falling

here and pencils are breaking there, and somehow it gets finished. Then

you throw it in the drawer totally unrequited and you forget about it.

Your life goes on and you kind of heal, you know? With the help of

psychotherapy you get through it. Lo and behold, 10 months later you

stumble across this piece, “My God, this is incredible!” You discover

it’s a window so far ahead of yourself and you know you didn’t write it,

because you consciously fought it every note of the way. I cannot explain

that other than divine intervention. That’s happened to me several

times. Now I don’t even question it. I just know I’m writing

something and I say to myself, “Oh man, this is like, uh, yeah, push,

push”. I think of one of my great teachers, Larry Wilcox, may he rest

in peace. He taught me how to listen. Technically, he was one

of my orchestration teachers. But, truly, he taught me how to listen,

and it was quite fascinating. He would say, “Get this particular score,

this edition. Don’t open it, I don’t want you to look at the score;

just pick it up and get it ready. Get this recording. I want

you to put it on, then clean your house, go grocery shopping or something,

just put it on wrap-around, let it play all day long.” In essence he

said, “I don’t want you sitting in front of the stereo; just put it on and

do what you do. At the end of the week I want you to sit down and listen

to it.” And I realized what he was doing subsequently. Because

the piece was written subliminally, it didn’t start necessarily at A and

went to Z. It may have started at P and then went to K and then went

to O and then somehow...

BD: Was this a well-known piece or...?

HW: Yes. What happened in the process, I realized my own processes in writing. This opera I just finished, Dracula Opera Erotica, I had written the opening monologue just to see if I could do it, because I had a revelation: I was asked to do incidental music for the Ted Tiller version as a financial assignment, strictly a journeyman gig. I’m sitting in the back of the house and I have this revelation. I said, “My God, why would Dracula die? Why would anybody – forget Dracula – why would anybody with 500 years of experience put themselves in a position of death?” I realized he fell in love. I thought, “Oh wow, no one’s touched upon this!” It evoked this whole thing, and subsequently it became an opera erotica. I realized the real twist on it was the Dracula syndrome in my opera is the unwillingness to leave our dreams. It’s not so much blood-sucking, it’s the other thing about dreams. How many dreams have we awakened from and say, “Oh, God, I want to go back.” The thing that’s also fascinating about that is in the dream context, whatever we think, if we freeze these moments, and we dwell in these thoughts, it’s longer than the microseconds, the continuum of life. So, if anything, reality becomes more the illusion and our dreams and our fantasies become more real because they carry more weight because of the time involved. But, talking about how this piece was written, I wrote the first aria. Then I thought, “Let me write an aria for Mina.” It turned out to be her final aria, and I said, “Well, let me write an aria for Jonathan.” That was somewhere in the middle. Then American Opera Projects had asked me, (through Robert Driver of the Philadelphia Opera, who suggested me to Greta Holby, look at this composer...) and they said “yes”, so they were doing it as a work in progress; we were doing the reading. So I wrote this section. I had to write the very end. Then the next time we did a reading there was another middle section that came in, and I just recently finished the remaining 40-minute hole. It’s very funny because you say, “Well, my God, how do you put these fragments of motifs together?” But a lot of times it forces you. You know, there’s a lot of Kismet involved. If I had to write it A to Z, I don’t think the piece would have turned out as well as it had. It’s one of those, like they say; “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”. I try not to explain it, I just try to do it. And so far it’s working, you know?

BD: Well, what advice do you have for other young composers coming along, if anything at all?

HW: Every day, every day, every day, every day. Don’t quit; follow your bliss. Listen to Joseph Campbell - he wasn’t so far from the truth – and work hard. Listen to everything. Don’t dismiss anything from listening. Find your niches, have your own opinions, never be arrogant. Have your likes and your dislikes, of course. But you never know, you may hear stuff that is absolute crap, it’s totally self-indulgent. But if you’re in the theater and you paid for the ticket, even if you hate it, sit through the entire performance, because then when someone does a point-counterpoint with you, you can at least say with authority “Yeah, I saw that, this happened, that happened, this happened.” Strangely enough, the negative vacuum that one of those experiences creates for you may turn out to be the most magnificent positive somewhere else down the line in application. I can’t tell you when I was at school how many things I learned and all of the stuff that didn’t mean anything until subsequently years later, through application, it was like this dusty Rolodex. I say every day because every moment of time that you concentrate and work on it, you’re refining your craft. Every time you refine your craft you refine yourself, because your craft is a microcosm of your life, and your life is going to improve, totally improve! I used to have a nickname, you can tell by my speed-rap. God help me if I ever drank coffee! Ladies and gentleman, I don’t drink coffee because I’d talk three times longer and five times as fast. It’s one of these things where you just keep working and refining your craft. You find that in this process of work, all these discoveries happen that you can apply in life. I had a nickname, the White Tornado, when I was young because I had this raging desire to be good. I mean, once again, the Grandfathers, and my father, who I respected – and he’s still alive – I respect immensely. My mother was an Earl Caroll Vanity Girl; it was show-biz all around me all the time. You deal with this, and you work, and you just don’t stop, you know? Finally I arrived.

BD: But at what point do you start to experience burn-out?

HW: That’s something else. I was the White Tornado because they would say, “Hayden, Jesus, man, you know, you leave a room and furniture spins.” I had this raging desire to be good! I hadn’t really developed my craft at that point. I had interesting ideas, you would say. I was a precocious kid, but not until I really arrived, and that’s not an ego trip. You just recognize that if somebody hands you an assignment and you know you can do it, history is going to be the only thing that can tell me whether I have really been good at my craft or not. It’s one of those ephemeral things. Whether my piece is going to stand the test of time, that is the true critique, and that’s beyond our control. Before that aspect, we say, “I can handle this and I can handle counterpoint. What’s that?” I can handle this, handle that, orchestration, and that’s a perpetual re-invention, a redefinition, a rediscovery. Like I said, every day, every day, every day. It’s not as painful as you think. Think about the poor people out there who have no direction in life and can’t find something. They go buy a $175 shirt to go disco-ing somewhere and they can’t even dance in time. At least we are safe.

BD: Safe from what?

HW: The anarchy that’s out there. The anarchy of ignorance, the anarchy of this growing illiteracy, the plague that’s out there.

BD: Do you not like people?

HW: I love human beings.

BD: You don’t like what people have become then?

HW: There are people and there are human beings. Look, we have Rwanda, they’re killing 5000 a day. We have Bosnia, we have Yemen, we have Somalia, Sudan, Uganda.

BD: We also have the Berlin Philharmonic, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the Metropolitan Opera, and the Chicago Symphony.

HW: Bless your heart! But the market share of those orchestras is rapidly shrinking because the corporate monolith recognizes GNP to be the base of the pyramid, not the apex. As long as we recognize the base of the pyramid and not the apex, and realize that with the world having six billion people that there’s a market share – and a profitable market share – no matter how secularly narrow any apex of any pyramid may be, we’re going to find ourselves in this widening homogenization to the point where we will not perpetuate a knowledge of what could first be investigated. People will not know of the classics, they will not know of this, they will not know of that.

BD: Should they?

HW: Yes! Because we are going to get into revisionism. Look at the racism today. You and I went through Thurgood Marshall, man, a titan! We went through the 60s. We went through putting everything on the books legally in America, making America truly what it should be. All of a sudden we have racism and revisionism like I can’t believe! I cannot believe that I went through the 60s to see this crap that’s happening now. And I have too many friends, as artists, as everything out there. That’s not what you are. I mean, that’s wonderful. You bring your culture to me. Sure, you bring this, you bring that. That’s a wonderful integration, that’s a great synergy. But there’s no color line, there’s no theological line. It’s “What are you?, What do you have to say?” Every time you talk you say, “I’m a this, I’m a that?” No, you talk. Now, all of a sudden it’s, “Well, I’m a this.”, “I’m a that.” “Oh, hi. I’m this, I’m this, I’m that.” I mean, what is this? Are you this? Have you accepted this? You don’t have to tell me what you are! Be! Be! Just do and produce. Don’t hate me. Do and produce!

* * * * *

BD: Okay, let’s swing this back to music. What IS music?

HW: Well, Music-Speak. It’s a different language, and

it’s a very fortunate language, because it transcends all ideologies.

The schism in music-speak is between the intellectualization of it and the

GUT, as I referred to Artur Rubinstein’s definition. I tend to be the

latter camp because I have to use my intellect to be able to grab you.

I’ve always felt that a true definition of art was this, and this is why

I think it’s from the gut: The ability to take a “spiritual” from the

cosmos, put it into a physicalized form, where another individual can have

that very same first-person experience as I had when I reached in and pulled

out that “spiritual” from the cosmos. Depending on how successfully

that happens with all the other people outside of myself, will determine

how successful I’ve been at my craft and, therefore, how successful I am

as an artist. Even if you can’t put the wherewithal to analyze it like

that, that doesn’t mean that you don’t have it to do it. It’s most

important to the listeners out there to find it, people, because it’s getting

to the point now that we don’t have very much left to keep our sanity and

to keep the humanity that is rapidly dwindling. We must keep our humanity.

The only way we can have our humanity is through the arts and the sciences.

The sooner we recognize that we are now going into a renaissance which is

totally predicated upon multiculturalism – and that means EVERYBODY, gang;

multicultural is everybody. I’m very optimistic, as bleak as things

seem right now – and they’re very bleak. I believe the world is coming

to an end, as it were. What that literally means? Well, we have

another six years to go, but the Renaissance is here. And I send the

word out to all you people, that those of you who believe it, you’re in it,

and it’s going to be amazing. Just think about that. All you

guys out there who are, say, at least 40 years old, who have witnessed the

television renaissance, meaning the 60s, imagine the computer renaissance

of the year 2000. These little pishers have grown up as if it’s the

telephone. They have computer-speak like we just talk. It’s very

exciting.

HW: Well, Music-Speak. It’s a different language, and

it’s a very fortunate language, because it transcends all ideologies.

The schism in music-speak is between the intellectualization of it and the

GUT, as I referred to Artur Rubinstein’s definition. I tend to be the

latter camp because I have to use my intellect to be able to grab you.

I’ve always felt that a true definition of art was this, and this is why

I think it’s from the gut: The ability to take a “spiritual” from the

cosmos, put it into a physicalized form, where another individual can have

that very same first-person experience as I had when I reached in and pulled

out that “spiritual” from the cosmos. Depending on how successfully

that happens with all the other people outside of myself, will determine

how successful I’ve been at my craft and, therefore, how successful I am

as an artist. Even if you can’t put the wherewithal to analyze it like

that, that doesn’t mean that you don’t have it to do it. It’s most

important to the listeners out there to find it, people, because it’s getting

to the point now that we don’t have very much left to keep our sanity and

to keep the humanity that is rapidly dwindling. We must keep our humanity.

The only way we can have our humanity is through the arts and the sciences.

The sooner we recognize that we are now going into a renaissance which is

totally predicated upon multiculturalism – and that means EVERYBODY, gang;

multicultural is everybody. I’m very optimistic, as bleak as things

seem right now – and they’re very bleak. I believe the world is coming

to an end, as it were. What that literally means? Well, we have

another six years to go, but the Renaissance is here. And I send the

word out to all you people, that those of you who believe it, you’re in it,

and it’s going to be amazing. Just think about that. All you

guys out there who are, say, at least 40 years old, who have witnessed the

television renaissance, meaning the 60s, imagine the computer renaissance

of the year 2000. These little pishers have grown up as if it’s the

telephone. They have computer-speak like we just talk. It’s very

exciting.

BD: I’m going to be keep bringing this back to music. Is the music that you write, or music that exists, the solution or is it part of the solution, or is listening to the music then going to produce the solution?

HW: Well, it’s funny you say, solution. To what, if I may?

BD: Solution to the problems that you’re talking about.

HW: Okay. I feel this. I’m not planning to be the saviour. I feel, though, that my music is accessible, and what I’m saying to those people who have only listened to rock-n-roll is there’s a power and passion that if you still yourself enough to hear the noise, you’d hear a noise that would knock you on your ass. I’m very sincere about that. I feel that I have a very passionate statement, and I hope the world likes my music-speak. I feel also that there’s a huge market share that can make tremendous revenue, because we’re talking about revenue. There are many great pieces. There’s a strange duality here. You could say, well, there are a lot of people who maybe have heard of "Dot, dot, dot, dah!" [singing the opening motif], the most famous motif ever, but they’ve never really listened to entire Beethoven Fifth. Then there are those of us who are real die-hards who are, “I can’t listen to that...” or, “I love you Ludwig, but I can’t listen to this anymore.” We have to be careful. We can’t be arrogant and look down on a person. They may not even have the attention span to listen to a whole thing. We have to think in pop nomenclature, like how about the single from it. Not to bastardize it, but we have to be willing. In opera, it doesn’t take years to develop a taste, it takes decades! It’s a glorious, complex art form; it’s brilliant, but unless you’re willing to give a sampler to people and hit them with some of the greatest arias and slowly work them in so they know how to listen and reach, if we don’t take the time to teach them, we’re going to lose them. So we have to not be arrogant and say we will play Beethoven’s Fifth. But at the same time, we cannot limit ourselves strictly to just the 12 or 15 pieces to play as a standard and safe repertoire, to hope that we’re going to keep our subscription audience up. We have to figure a balance of working it in. The one thing I miss about Bernstein - granted, there are few pieces that he wrote that are absolutely brilliant – to me his genius, his legacy was as a teacher. We need another series of Young People’s Concerts, not condescending, but to educate us to the glories and the mysteries of music. Not something so fantastic. I’m thinking of the movie Amadeus, where Mozart says something about “crapping marble." I always refer to the “boys” and the “gals” by their first names because they were real people. We look at Guns and Roses today, with Axel, but think about Ludwig. Here we are having a beer in some local pub, and this guy comes in disheveled, and goes and throws open the lid of the piano, blows the piano apart with some improvisational wizardry of his, laughs uproariously, slams the lid down, and storms out of the joint. You’re left with "who was that, what was that?" He did that kind of thing. He moved 30 times in his life. He was crazy. He was also brilliant. These are real people. It’s very exciting. If we examine this, you start saying, “Wait a second, that’s us here!” Then you start tying in today and you start taking what could be the rock forms and you’re expanding them, or the folk forms, people are trying to expand their ideas in a smaller folkism and you try, like two converging trains meeting at Promontory Point, that’s what happens in music. It’s an inductive, ephemeral trip. You get the idea.

BD: Sure.

HW: I’m a strong believer of that. There’s too much going on, and there are too many secrets, too many well-kept secrets that are there. With everybody trying to free-express, there’s a way to show alternatives, alternatives, alternatives. There are so many alternatives.

BD: You list all of the good and all of the bad. Are you optimistic about the whole future of music?

HW: Yes.

BD: Just like that, “Yes”?

HW: Because I’m still writing.

BD: In other words, if you couldn’t write anymore, you would not be optimistic about it?

HW: How could I write otherwise? That may sound smug, but it’s honest. With all my concerns for humanity – and they’re very deep – I once heard someone say, and I thought it was callous at first, but there is a truth to it: “My arms are really too short to embrace the world.” I can really do more for the world if I embrace myself – and I don’t mean in a greedy selfishness. I’m talking about perfecting myself, perfecting my time on earth. We’re here, we’re gone! I was in a car accident where I died and I came back. I destroyed my body. I hit a wall in a car. The only reason I lived is that I was 17, and I had long hair, so I didn’t bleed to death; it matted. Now it wasn’t like in one of these Hollywood movies where you wake up the next day and you go, “Oh, there it is, there’s the vision.” and I could become an evangelist. No, it’s not that at all. The rude awakening was that [snaps his fingers] life’s gone, baby. And then when you come back, and there's this, the nuclear heat. It’s almost like Mary Shelley, the Frankenstein thing, not so far from the truth; coming back, maybe it’s all the mitochondria turning back on and the body heat of regeneration. I don’t know what it is, and granted, that’s a conjectured hypothesis, but it felt awfully real to me. I’ve never felt such heat in my life. The only reason I lived, I think, was the durability of youth. But that recognition as I was going on 17, and then I fell in love, and that was wonderful, like the beginnings of life. But the one thing was like, well, where’s this revelation, where’s this revelation? But the one thing that kept hanging with me was the real consequence about termination. Then you start to realize how long are we going to live. What are you going to do?

BD: You want to make sure that you leave enough stuff behind.

HW: Well, yeah, but that’s ego. But think about this: There’s something that ties us in with Creation itself, the glory of Creation. Forget theology, just focus on God, creation. What happens is you stop time. Are you bored? Create, find a focus; you won’t be bored ever again in your life. You may get mishegosh. You may get crazy and depressed and tremendously anxiety-ridden because things aren’t formulating the way you wish them to formulate, but you won’t be bored. Boredom is a killer.

BD: Is that all we’re trying to do, just escape boredom? Isn’t there something more than that?

HW: Yes there is. Touché! But, unfortunately, most people are trying to escape boredom with all superficial means, and it begets the devolution which begets continuing devolution, and look at society today. We have a society of very unhappy people, lost people, where money becomes the thing. Don’t get me wrong, I want to be able buy my family things, be able to educate my children and buy health insurance, thank you very much, but the bottom line is, to get lost in that, you get stuck in one direction, that becomes insignificant.

BD: Are you only writing for the people who are lost?

HW: No, no, no, no, no.

BD: The people who are already found and have good lives, it doesn’t matter to them?

HW: No, I’m only writing for me. I’m not saying that to exclude my discoveries, I’m writing because that’s the pure honest experience I’m having with the cosmos. I’m showing a view of the world that I’m seeing, and if it ties in and moves you, too, then we’re sharing this experience. Being in a hall together where we’re all having this experience becomes an amazing cosmic experience. Taking the focus off me, for the individual to find a focus to do anything, whether it’s weaving, it’s painting your apartment or doing interior design, is helping people, even being a good businessman. I’ve always found it very curious, as an aside here, why business all of a sudden looks at a GNP and finds it’s more important to fire 4000 people to raise the profits 5% and give the CEO a big bonus because he’s done this for his stockholders, as opposed to educating his work force and increasing his work force to be a better buying work force. I’ve never met anybody well-educated who wasn’t a good buyer, but a buyer nonetheless. And when you buy, you make profits, so that’s something else. It’s the same thing with art, and it’s the same thing with life. I don’t mean to sound like a half-cocked guru here, but all of this has come out of this microcosm, this metaphor of my application in art, in my writing music. I recognize how completely my life has changed, how people regard me, because I’m not hysterical anymore. Now, granted, in this talking, you can see how fast my mind is working cause I’m formulating ideas, but when I’m writing I’m not talking. It’s different. I sit down and play a piece for you, you listen in your own space. That’s me. And like, “Hi, Hayden,” “Hey, hi Bruce.” It’s that kind of thing. I like where I am now. It’s a lot easier. [laughs]

* * * * *

BD: About your recordings, does it please you that other people can listen to your work at remote times? Even when you’ve moved on and are writing something different, they’ll be able to listen to what you wrote last week and last month and last year.

HW: Oh, absolutely. I’ve written around 400 pieces now, over 400 pieces. Some are better than others, some I’ll re-scrub and work because they may be good germs, and some of them may be just terrible. It happens, but yes, it’s very nice. One thing I’m trying to do with my colleagues – and I raise an eyebrow here and there – is I use pop and rock nomenclature when listening to my work. I say, “Well, listen to the single.” They go “What?” “Yeah, the single. The 6th movement. Listen to the single.” Now I know that sounds rather strange, especially for the purists who pride themselves as having an ability to sit through a Ring Cycle. I have that ability. It’s a strange ability, and I’ve worked it up for a long time. I’m 45, I’ve been in music for 40 years. It’s taken a long time to have that type of discipline. It isn’t necessary for everybody, but if you want to listen to the Ring Cycle, you have to have a discipline to be able to sit through it.

BD: Do you need discipline, or are you just simply enjoying the damn thing?

HW: Good question! One would immediately say, yes, you’re

enjoying the damn thing, right? I saw a documentary on one of the Van

Cliburn competitions, and someone was talking about how audiences now go

to concerts expecting to be entertained, as opposed to willing to work.

I don’t mean that you’re going to go to a concert where somebody’s going

to educate you and hit you over the head, but I mean this synergistic intercourse

of what’s going to happen and where are we going to go and that’s exciting

to me. That’s real theater, where you’re part of it. There’s a

proscenium edge, but why aren’t you part of that proscenium edge even if

you’re sitting outside the fourth wall? When you have that, everything

becomes exciting! We were talking before about the end of the Mahler

Ninth, and that pregnant pause when the baton was put down and the

violins relaxed, and the audience still was caught up in that magic.

And finally, maybe it was even the shock of the whole of that, that emptiness,

that silence, and they exploded! Well, isn’t that amazing, wasn’t it

wonderful!

HW: Good question! One would immediately say, yes, you’re

enjoying the damn thing, right? I saw a documentary on one of the Van

Cliburn competitions, and someone was talking about how audiences now go

to concerts expecting to be entertained, as opposed to willing to work.

I don’t mean that you’re going to go to a concert where somebody’s going

to educate you and hit you over the head, but I mean this synergistic intercourse

of what’s going to happen and where are we going to go and that’s exciting

to me. That’s real theater, where you’re part of it. There’s a

proscenium edge, but why aren’t you part of that proscenium edge even if

you’re sitting outside the fourth wall? When you have that, everything

becomes exciting! We were talking before about the end of the Mahler

Ninth, and that pregnant pause when the baton was put down and the

violins relaxed, and the audience still was caught up in that magic.

And finally, maybe it was even the shock of the whole of that, that emptiness,

that silence, and they exploded! Well, isn’t that amazing, wasn’t it

wonderful!

BD: It was. It was great...

HW: ...because the audience was just as much a part of the music, and even more, as a part of the performance. That’s because the audience came with anticipation, not an expectation, an anticipation to work. Okay, this is Mahler and we’re going to do this and we’re going to listen. We know it’s long, but here we go. We know this is beautiful music here, but there are some “buts” here, but the “buts” disappeared, because they were working, they were focusing, they were concentrating. Very exciting!

BD: Do you want that same kind of audience for your music?

HW: Oh, I would love it! At the same time, I think the greatest compliment you can give anybody. For instance, the Steely Dan album, Asia, it’s a masterpiece. And why? Because it could be Muzak. At the same time you could sit and go, “My God, this is brilliantly well-executed, brilliantly well-written, brilliantly well-performed, brilliantly well-engineered and produced!”, and yet at the same time you could dismiss it and it doesn’t interfere. When you get into symphonic music, it's more complex and sometimes it will demand more of your attention. I’d be hard pressed to play the 6th Movement while we’re eating soup, when the African percussion comes in and blows the roof off. But, at the same time, there’s an aspect if you just let it happen. For instance, when we were taught in school about James Joyce, Romulus Lenny said something that I thought was quite astute. He said, “Don’t get stuck. If something confuses and you didn’t get it, don’t stop; keep going on and let it wash you. Finally it will pull you along." Interestingly enough, and this just hit me, it’s the same thing that Larry Wilcox had said: just let the music play and come in. Do your errands, go out and catch it here, catch it there, and then, finally, it will all come together. I can’t tell you in my youth how many times with him I would say I really like that one piece of his, but that second piece, eh. He said, “Listen to it again.” And then, in retrospect, I can’t imagine how I ever had any doubts about the piece; it seemed even more melodic than the piece that I first liked that was more accessible.

BD: That goes back even to Koussevitzky.

HW: Absolutely, no contest.

BD: He would play some new music and the people would say, “Oh, I’d didn’t care for that,” and he would say, “Fine, I’ll play it again.” [Laughter]

HW: Good for him, good for him. In some cases, it deserved to be repeated with the expectation of a positive response, and then there were the responses that would be cryptic responses. That’s the nature of the piece. There will always be cryptic responses. The only differential that I have here is that is an entire plate of differential, of cryptic responses enough? For me, it’s not. I really feel that nature is a romantic beast. That the real beauty of being human is to truly be romantic and to truly recognize what hurts when you have been hurt. Then, in that recognition, try to overcome your pain, not in vengeance to inflict that same hurt on somebody else, but extend passion, a positive passion, a love passion to eradicate your own pain and hopefully have reciprocation. We know how complex the human machine is, and you could go through those motions and still get your brains kicked in. The bottom line is, short of stupidity and shortsightedness – because one has to defend one’s self; I mean, this is an insane society we live in – I feel that if we try, we will find what we’re looking for. If you don’t look, you certainly will not find it. Even if it lands on your lap, you’ll say “What was that?” and you’ll brush it off, and it falls and breaks. You have to have soft hands. Baseball, baby. Everything is baseball. Be a shortstop, you know? Catch that, catch that, catch that, no matter where it’s thrown.

* * * * *

BD: Are you at the point in your career that you want to be right now?

HW: I like my life. I like what I’m doing. I like my vision quest. Something must be working. At the same time, there’s tremendous neurosis that I feel like I haven’t written anything and there’s so much more to do! It’s Sisyphus every day, every day, every day.

BD: Would it be helpful if you could just take the top of your head off and just sort of pour it out onto the page and then put the top of your head back on?

HW: Well, I kind of do that anyway. I’ve always said writing a piece was like looking into a bucket of sand and trying to figure out the chronological progression of the grains. So if I open the top of my head I may spill out extra notes I didn’t need to spill out, and I’d really have a problem.

BD: When you’re writing a piece, how do you know when it’s done?

HW: It’s done. [Pause] I know, but that’s also a very

good question, because if I don’t feel requited, something’s wrong.

Yet there are those pieces that are beyond me that I just finish and I throw

‘em in the drawer and then I discover them a year later and, “Wow!” Or, “Oops,

well, that was good.” But nine out of ten times they were used somewhere

else and they’re right unto themselves. That’s what I meant when I

said I had arrived. I recognize balance, sectional balance form.

I have a tremendous understanding of form, and I play with form all the time.

Whether something’s through-composed and it’s hanging almost like a Caulder

mobile, or, or it’s some bastardized sonata form, I kind of like sonata form.

Why I say “bastardized” is I don’t get into the diatonic progression.

I get into it as a formic progression of saying, “Okay, we have exposition

here,” but what is going to happen in the exposition? Exposition, antecedent,

development... you have recapitulation, post-development and coda,

alright? But you say we’re in the exposition, or do I want to just

have an “A” section, or is it going to be binary or ternary or compound rondo

or some bastardized “through” whatever? Then somehow it resolves itself

and I say, “Okay, antecedent.” It helps me write.

HW: It’s done. [Pause] I know, but that’s also a very

good question, because if I don’t feel requited, something’s wrong.

Yet there are those pieces that are beyond me that I just finish and I throw

‘em in the drawer and then I discover them a year later and, “Wow!” Or, “Oops,

well, that was good.” But nine out of ten times they were used somewhere

else and they’re right unto themselves. That’s what I meant when I

said I had arrived. I recognize balance, sectional balance form.

I have a tremendous understanding of form, and I play with form all the time.

Whether something’s through-composed and it’s hanging almost like a Caulder

mobile, or, or it’s some bastardized sonata form, I kind of like sonata form.

Why I say “bastardized” is I don’t get into the diatonic progression.

I get into it as a formic progression of saying, “Okay, we have exposition

here,” but what is going to happen in the exposition? Exposition, antecedent,

development... you have recapitulation, post-development and coda,

alright? But you say we’re in the exposition, or do I want to just

have an “A” section, or is it going to be binary or ternary or compound rondo

or some bastardized “through” whatever? Then somehow it resolves itself

and I say, “Okay, antecedent.” It helps me write.

BD: Are you deciding this, or is it deciding it.

HW: It decides it a lot of times. I’ll tell you something funny: In film-writing, a lot of times, if you look, at the film – and in writing, I get an improvisational sense. I sense, “okay, this is the mood that I want to set here.” When I look at it, I might see that he grabs the knife, and I’m looking and I’m figuring where I am with my tempo. I want these actions to happen on a downbeat because it becomes strong, it points up the film. All of a sudden my bar lines start dropping in at a certain place, so I may have a 3-minute section of music that I’ve already written out in 2/4, 5/4, or 7/4, and it’s all laid out before I’ve even written a note of music! Then, I did a film called Buckets, with Harry Mantheakis who wrote and directed it. Being a silent movie the woman had a theme and an instrument and everybody does their thing. All of a sudden, when she did something, well, I was blocking these out before I still had written a note of music! I knew my tempo, I knew where the entrances were happening. I knew what the orchestration was going to be once I figured out what the melody was. And it came out, boom! And it worked like a hand in a glove. So yes, it can dictate to you. But also, at the same time, I’m not going to jump into the next section if I’m working in a bastardized sonata form. I won't move into the antecedent from the exposition if I don’t feel that I have come to some kind of cadence or some kind of momentary resolution... or is it a final resolution? That kind of thing happens all the time.

BD: This is a technical thing that you picked up on. Is that something that everybody picks up on, or just something that everybody knows is there but can’t put their finger on?

HW: All of the above. It depends on how cognizant we are through what we allow ourselves to become cognizant of. I know that sounds like double-talk, but, how can you know what Mark Twain said if you don’t read Mark Twain? How can you know what a Beatle song sounds like if you haven’t listened to a Beatle song? It’s this kind of thing. You can’t shut down. You have to allow the options, and then something will speak to you. I can’t tell you how many conductor colleagues who will say, “This piece, well, yes, I can conduct it, but it doesn’t really speak to me." It may be fingernails on the wall to you, and it doesn’t speak to you at all. But that’s the nature of it all.

BD: Do you expect your music, then, to speak to everyone?

HW: I wouldn’t be so presumptuous.

BD: Do you expect your music to speak to anyone?

HW: Absolutely! And to a large financial market share. You’ve got to remember something: We’re talking classical music, so 5-8000 units is considered a rave sale, when you consider that we, who are 40 years old, 45 years old, and older, by the year 2000, just in America, are going to be 75 million people. If I sold only to one one thousandth of that group, I’ve sold 75 thousand units. So, I ask you, if 5-8000 units is a rave, and I’m only trying to deal with one one thousandth … It’s remarkable the way we’re getting back into a cottage industry. There are ways of putting things out. You just put them out and you work together, and you put them out. There is a market. There is a definite market.

BD: But you would keep writing even if there was no market?

HW: I have to. The sad part for me is that the rest of the world wouldn’t be hearing this joyful noise that I’m hearing. If you could put your ear next to mine and hear what’s going on in my head, you’d hear a lot of everything at once. [Laughter]

BD: Would it sort itself out?

HW: No. It’s funny... I mean excuse me if I really sound so self-involved when I say that, it’s just that I’m so excited when I’m “up”. I could be depressed and say, “Oh, it’s not coming,” or frustrated, and go into fast spin-cycle in bed, chewing up the insides of my mouth. It isn’t easy; don’t let me make light of it. You have to really be tenacious. You have to have discipline. Discipline is not an extension of sexual behavior, as many may think; it’s a way to set yourself free. You put in the time in the beginning, it pays off in the end. Look at Nolan Ryan. He broke his ass after every game – working out, working out, and that’s why he was a legend. I mean, tremendous respect. That’s an artist of baseball. Because of his focus and his discipline, he recognized what he had to do. Imagine, to be able to throw a ball as fast as he did for as long as he did without any physiological problems. It’s staggering. I always said, “Nolan, come back to baseball, get a knuckleball, and pitch until you’re seventy, it would be great. Pitch when you want, but just come back.”

BD: Are you going to pitch till you’re seventy?

HW: Oh, I have my work planned out a long time. I have

romantically felt that I’d work at least till I was 95, and in my 95th year

I was going to be contacted by extraterrestrials and travel at the speed

of light and voyage to other worlds. Maybe that’s a romantic way of

saying that’s when they’re going to come and get me and I’m going to expire.

I would even hope to live longer than that, as long as I could keep writing.

and not drool on myself. [Laughter] Isaac Asimov, very possibly

another DaVinci of our time, went to his death with the satisfaction that

he had written down every idea he had ever had. What got him freaked

out when his body was dying, his mind was still solid, and his mind strangled

in a dying body. That’s kind of scary. It’s almost Stephen Kingish,

you know? But think about that. He worked, he killed himself.

He was at the typewriter something like 17 hours a day. I don’t recommend

that for everybody, but, if the spirit moves you, bless your heart.

HW: Oh, I have my work planned out a long time. I have

romantically felt that I’d work at least till I was 95, and in my 95th year

I was going to be contacted by extraterrestrials and travel at the speed

of light and voyage to other worlds. Maybe that’s a romantic way of

saying that’s when they’re going to come and get me and I’m going to expire.

I would even hope to live longer than that, as long as I could keep writing.

and not drool on myself. [Laughter] Isaac Asimov, very possibly

another DaVinci of our time, went to his death with the satisfaction that

he had written down every idea he had ever had. What got him freaked

out when his body was dying, his mind was still solid, and his mind strangled

in a dying body. That’s kind of scary. It’s almost Stephen Kingish,

you know? But think about that. He worked, he killed himself.

He was at the typewriter something like 17 hours a day. I don’t recommend

that for everybody, but, if the spirit moves you, bless your heart.

BD: Well, if someone sits at the typewriter 17 hours a day, how are they going to have time to listen to your music?

HW: You know the funny part of that is, if it is meant to be it will happen. Interestingly enough, those who will be working that hard to create, it’s OK if they can’t. We need that input. Somehow we always manage to hear each other’s work, because if it’s important enough, in the honesty of what we’re saying, we help massage each other into creating. We get inspired by each other.

BD: Music is the massage?

HW: Good art is the massage. All honest expression is the massage. I once saw a deaf girl, she was a young woman. They had these earphones on her, and they were trying see if she could hear. She was really stone deaf. They were trying some technique through the ménages, certain vibrations, and they were scrolling through the radio. There was talking, and all of a sudden they passed a station and it was Beethoven, and she responded. I started weeping. She heard SOMETHING that made her respond that she had never heard before. Something that I take for granted. Well, I don’t. I constantly have my fingers in my ears when things get too loud. I don’t want to lose my hearing, but it’s something that we take for granted. Was that an art piece? No. But it was a part of humanity that was so bloody real that it moved me! Once I saw a docudrama about Delius. I was so bloody moved by it, I sat down and wrote the major theme of what subsequently became a street opera of mine, Neon. How do you explain these things? It’s not the first time this has happened. How many times have we seen a great movie, walked out and said “Wow! The world looks different." These are very exciting moments. Other artists have created this, but all of a sudden we’re tingling with this world. This is what I was talking about before. So when we’re talking about Mahler, the audience has had the luxury of sharing a cosmic experience. This honest cosmic experience has massaged them, and hopefully massaged them enough that a lot of them will go home and make love to each other, or make love to themselves or explore in this ecstasy of glory that they have felt that they’ll try to do something, try to reach for something, straighten up their room, something positive, reach for themselves, try to write something down.

BD: Is that the purpose of music.

HW: One of them, I’m sure. Music is a form of expression. It’s another language. It’s Music-Speak. It’s to communicate. Is the purpose of writing to uplift and convey, or to open a window of something where all of these things happen anyway? I don’t think a good artist just sits down – unless it’s maybe like in a political connotation; “Well, I’m writing this because I’m angry, and here’s this very parochial emotion of mine, and I’m going to hit you, bang, and this is my emotion!” Now, that’s real, too. I’m talking about in the context where something is so spiritually uplifting where you carry that partial of that spirit with you, and you’re so moved that you feel that you have to do something within yourself as well. I feel that’s very real. I’ve seen that with paintings, I’ve seen that in movies, certainly I’ve read it in books. I remember, as a kid procrastinating and that next day was a test. I hadn’t read the book and I was BS-ing my way with the teacher. Finally with the test the next day, I sat down and read the book. The next thing I knew I had finished it. I was flabbergasted! It was Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck. I was devastated! For two weeks I walked around moping like I was lovesick. I was just so overwhelmed by the majesty of the humanity of this book. When George is saying to Lenny, when Curly is slapping him around, “Don’t take it, don’t take it,” and Lenny grabs Curly's fist and crushes it. Moments like that and, “Tell me about the rabbits, George, tell me about the rabbits.” And then Candy with his dog, when Curly so cruelly has the dog destroyed and Candy just turns to the wall. The dignity and the pain of that was so profound for me, such an amazing moment. Now, there’s an example, and that carried with me and I felt like I had to go to the piano and do things. It’s that type of transference.

BD: Since Carlisle Floyd has already turned it into an opera, did you just have to write your own response to it?

HW: Well, yes, or even just improvise or something. I just had to sit down at the piano and practice or play. You know? Emote. And that’s what happened. It’s not so strange. All of us have our own vision, our own problems, our own realities. But there’s a way, somehow, to clean it up, set it, and set it in motion in such a way that it helps us. It just perpetuates itself. It’s almost like a geometric progression. As insanely cruel as the bad cards some people have been dealt in life, there is still a way to turn it around. I firmly believe that. If I didn’t believe that, then I would say the world is truly coming to an end. I’m a Romantic. It’s incongruous. It’s oxymoronic. A renaissance is coming and it’s going to be phenomenal. Look, we have a plague now. I mean, they’re estimating 70 million dead in Africa alone. We’re talking about Malthusian philosophy, really, coming to the foreground. When I was in economics and we studied Anida and Humana, all these utopian phenomena that failed, we looked at Malthus who said that plague and war and famine were necessary evils because they thinned out population. The teacher was very quick to show us that the Second World War only had killed a half year’s population growth, so obviously that was wrong. Now we have a real plague. We have a lot of wars going on and wanton killing. As scary as that is, it’s getting to my point. We will find a cure to AIDS, but the thing that’s going to happen that is so scary and miraculous in the process. Even if we can’t eradicate the virus, if we figure out a way of getting in and stopping its process of replication, we will have cured every single disease that exists and stopped ageing. So, you know, we look at this. We’re on the threshold of a heavy concert, and everybody’s playing. This is group participation.

BD: It will be interesting to see how many of these things actually

pan out.

BD: It will be interesting to see how many of these things actually

pan out.

HW: It’s all going to pan out.

BD: I guess it will be interesting to see when it pans out.

HW: Ah! Yes. I do feel that in our lifetime they will certainly have found a cure, or, let’s say, a preventative of death from the standpoint of AIDS. These retroviruses are very curious, but look what they’re doing now with cancer, with genes. They can tell now who is probable. That in itself is preventive medicine. I’m a very big advocate of preventive medicine, and it’s cheap! It’s a hell of a lot cheaper acting than after the fact. We need to start getting these bloody insurance companies that are just gleaning off the top and tell them to put a preventative medicine package together and authorize that everybody gets gene testing. So we see from birth, boom , you get fingerprints, you get this. Let’s get genetic fingerprinted immediately. Then we know the process. If somebody’s prone to diabetes, then they know not to get into heavy sugar consumption. There may be ways to prevent us from having to go into insulin that we can just homeopathically avoid all these pitfalls. And that’s cheaper. Let’s face it, with all the people that are propagating on this planet, we’re going to have to find shortcuts or we’re all going to die. Very few people are going to have the wherewithal to even buy medicine because everything’s going to fall out the window. We have to recognize this; we have to educate ourselves and we have to take care of ourselves. These are two inalienable rights that are not mentioned in the Declaration, but they are inalienable rights. Everybody deserves an education and health so they can pursue their happiness, which is an inalienable right. I believe that that’s what the renaissance is all about. I really do. I told you I’m a romantic.

BD: Hope it comes true.

HW: Well, I’m going to make it come true for me. I’m going to try at least [laughs].

BD: Thanks for coming to Chicago.

HW: My pleasure. Thank you.

=== === === === ===

---- ---- ----

=== === === === ===

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on June 6, 1994 at the studios of

WNIB. Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in later that

year, and in 1998 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2007 and

posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.