Virgil Thomson

The Composer in conversation with Bruce Duffie

Virgil Thomson

The Composer in conversation with Bruce Duffie

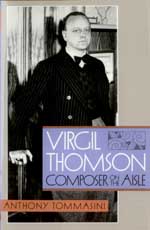

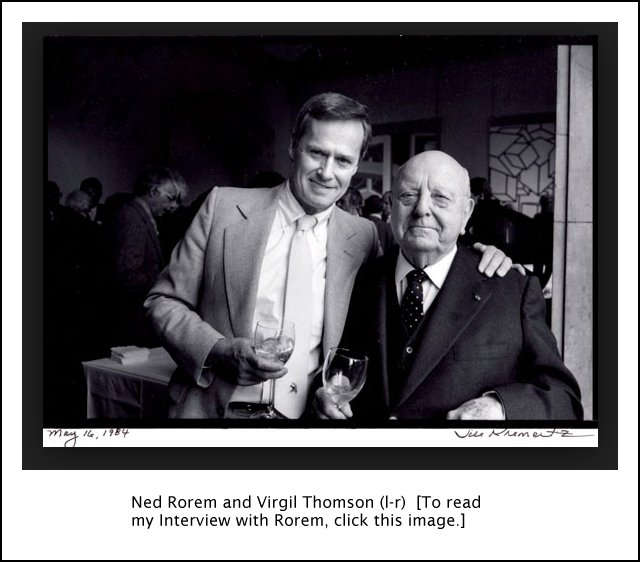

Over the years, I've had the privilege and the pleasure of interviewing performers and creators of so-called Classical Music. Some have been well-known, others labor quietly without much general recognition. A very few are larger-than-life figures who dominate the scene. Virgil Thomson was one of those major icons.

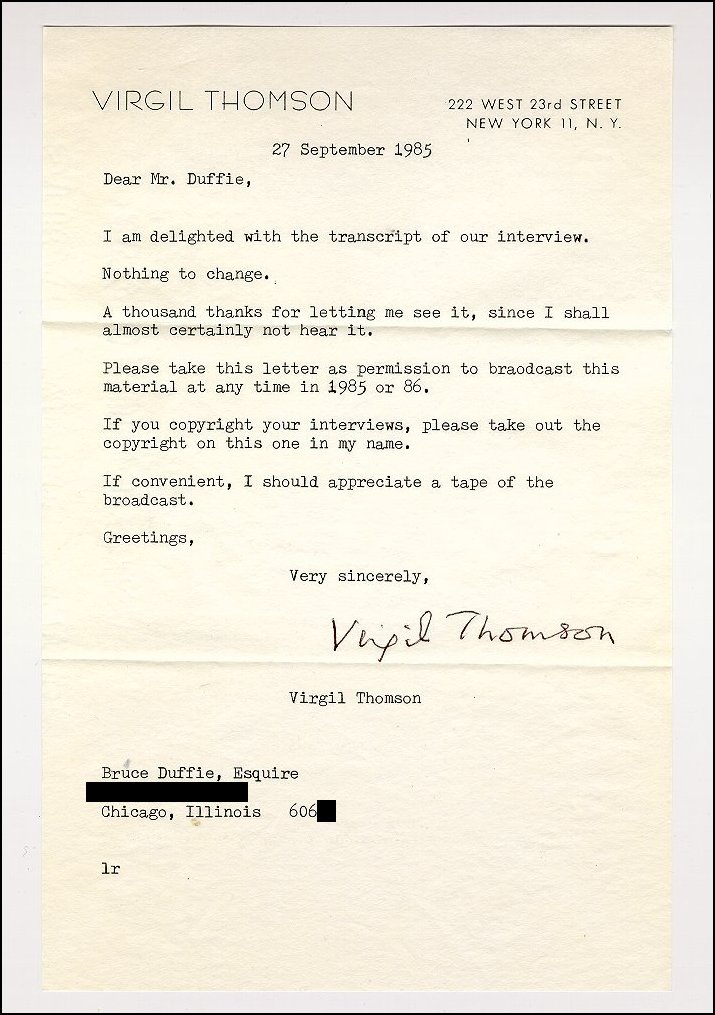

When setting up the conversation early in 1985, I'd told him up front that besides the usual concert music I wanted to inquire about his operas. He was happy to speak with me, and during the course of our 60 minute chat, he occasionally corrected my words, and even admonished me about some vague questions with imprecise language. In the end, though, he was pleased, and gave me a cheery "Right-oh!"

Here is much of our encounter.........

Bruce Duffie: In Baker's Biographical Dictionary, Nicolas Slonimsky mentions that you've 'achieved a popular universality in music.' [See my Interview with Nicolas Slonimsky, which includes a photo of the two of them together.]

Virgil Thomson: I don't know what he means. 'Popular universality' means that everybody loves you. He may be referring to the fact that my music, melodically and harmonically is what is often called 'available.' That is to say, you can understand it if you try. I think that's what he means.

BD: The public can understand it if its tries?

VT: Yes. Still,

sometimes it is, but it's not always deliberately obscure.

VT: Yes. Still,

sometimes it is, but it's not always deliberately obscure.

BD: When a composer is writing music, should he write for other composers or should he write for the public?

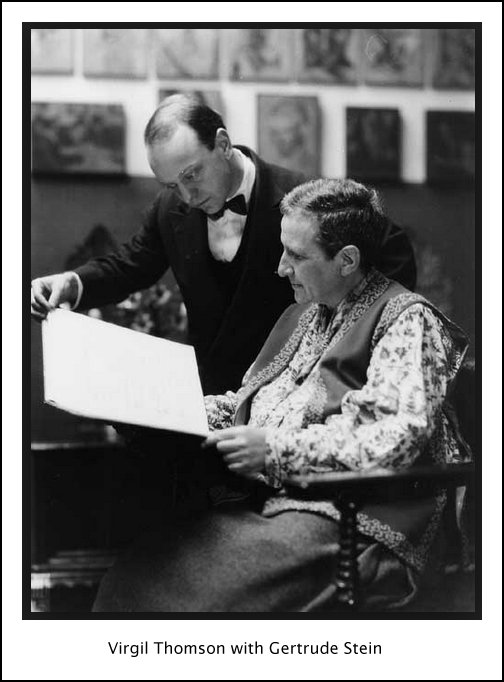

VT: (laughing) My old friend Gertrude Stein, when they asked her who she wrote for, said, "For myself and strangers."

BD: How much can the composer expect of the public?

VT: You can't expect anything.

BD: Nothing at all???

VT: No.

BD: How much should the public expect of the composer?

VT: The public has no obligations. The public has paid for its ticket.

BD: That brings me to one of my favorite questions: Is opera art or is opera entertainment?

VT: It better be both if it's going to be any good. Entertainment which is not art doesn't survive very long. It might run for two or three years and then it's over. Operas that survive a hundred years in repertory have to be a little more than casual entertainment.

BD: Is the public always right in its decision?

VT: No, no. The 'public' doesn't exist. There are only individuals who buy tickets and sit there. Sometimes they're twos and threes and they chatter about it afterwards, but there is no such thing as 'a public.' There are no voting boxes. There's no record of public reaction. Any public is likely to applaud, you know. But when different publics applaud night after night, then you have kind of a run and you're said to be successful. But still there is no test or description of who these people are because they're different all the time.

BD: Today, we have such a huge market for commercial recordings, is the public not 'voting' for a piece of music or a performer by purchasing those discs?

VT: No. A purchase is not a vote. A purchase is a trial. You may have heard it and think you'd like to hear it some more, so you buy one. They're not all that expensive. You have it around the house and you play it, but this has nothing to do with 'public.' It's absolutely solitary.

BD: Are recordings a good thing?

VT: Why of course! So's handwriting. So's a typewriter. Any form of reproduction is marvelous, terribly useful. The frozen performance has a slight monotony about it. It always comes out the same way. A live performance always comes out a little bit differently each time. But one doesn't kill the other. On the contrary, in the general practice, recorded music has been accompanied by an enormous development of the concert trade. One helps out the other.

BD: How can we get the public that sits home listening to recordings to come to some or even more concerts?

VT: Oh forget about the public. There's no such thing. Do you think you're 'public?'

BD: I'd like to think I'm part of the public.

VT: I think of you as a public of one. What's in a concert hall is a whole batch of ones... unless you get them all worked up by playing Stars and Stripes Forever. It's a beautiful piece, and they all kind of like to listen to where the piccolo comes in, and they smile. But they would smile if they were not in a large or middle-size auditorium. They'd smile at home.

BD: But would they smile at home?

VT: You'd have to watch and see. You'll have to do a little research on that if you want an answer. Perhaps put a little camera in the room..... There are a lot of ways of finding out what people do by themselves if you need to know. I'm far more interested myself in what they do alone than in what they do in gangs. On the other hand, if lots of people buy lots of tickets to hear my music, then I'm very pleased.

BD: OK, then, what about

the people who only play discs at home?

VT: Recording is the carrying of the public into individuals and its final and ultimate limit. One person alone in a little room listening to a recording. That's no public. The number of records sold is a commercial report. When they turn things on in elevators, and nightclubs and barber shops, there's no public there, either. It's decor or wallpaper. It's furnishings, and tends to create a certain lack of attention.

BD: Is that lack of attention carried over into the concert hall?

VT: It's carried over everywhere. Even with music lovers or musical addicts, the lack of attention is characteristic of a world in which the ear is drenched constantly with some kind of musical sound.

BD: So you would object violently if you were in an elevator and heard some of your music?

VT: I do not get violent in elevators. In former times, when my hearing was better than it is now, I used to ask taxi drivers to turn off the music. Now I don't hear it very much, so it doesn't bother me. But they would ask if I didn't like music, and I'd tell them I'm in the business and live with it all day long. I don't like to have it surrounding me involuntarily. It might be a piece I'm particularly fond of, but I still don't want any music at that time. It might even be something you habitually tolerate, but you don't have to have it rubbed in.

BD: Are the concert halls broad enough in their repertoire?

VT: They're not responsible for what people play in them. But people go to concert halls to hear live music and not records. They can hear records or the radio by staying at home.

* * * * *

BD: Some years ago, you said that the supply of ideas for innovation is failing. Is that still true?

VT: I do not know. I'm

not in the innovation business. Sometimes I had new ideas and sometimes

I had new ways of using old ideas. Innovation is not a word I use to

test quality on my work or anybody else's. It's a word that my friend

John Cage is particularly

fond of. He likes to assume that unless there's something that he can

define as innovation, a musical work is virtually without value. But

that's his own assumption, and also the assumption that he's capable of spotting

and divining what is innovation.

VT: I do not know. I'm

not in the innovation business. Sometimes I had new ideas and sometimes

I had new ways of using old ideas. Innovation is not a word I use to

test quality on my work or anybody else's. It's a word that my friend

John Cage is particularly

fond of. He likes to assume that unless there's something that he can

define as innovation, a musical work is virtually without value. But

that's his own assumption, and also the assumption that he's capable of spotting

and divining what is innovation.

BD: Do you feel that music is in a decline?

VT: That's something else. It does not have to do with innovation. It has to do with inspiration. Inspiration goes up and down. Innovation is practically a constant. Anybody can think up something a little bit new.

BD: Is inspiration on an up or a down at the moment?

VT: Oh I think all the fine arts are in a low curve compared to what they were 50 or 75 years ago. Oil painting, poetry, music. They're not as spectacularly fresh today as they were.

BD: Is there a single, simple reason for this?

VT: No, there's no reason for anything that I know. I can't answer any question beginning with "why." Things in this world do go up and down, you know, and the better brains today are less occupied with the fine and liberal arts than they were in 1900. Brains of today are enormously occupied with international organizations. The arts of war and physics, genetics. The novelties and innovations today are practically all in science and politics.

BD: Are the arts getting left behind, then?

VT: The arts are a little less striking than they used to be. The other things are far more striking.

BD: As recently as 20 years ago, you were saying that we, as a society, had recognized the arts and artists as a national wealth. Is this still true today?

VT: I'm not sure that we do, and certainly not as fully as older countries in Europe. The United States government is paying out a little bit of money - several million dollars - to the arts. They pay a lot more for sciences.

BD: Should the government be paying more of our money for arts?

VT: I don't have a vote in the matter. I always like to get more for arts, but I wouldn't like to get it at the expense of scientific research, which I think is probably more likely to give us valuable results today than just indiscriminately - or even discriminately - patronizing artists.

BD: But this doesn't ascribe that one is more important than the other, does it?

VT: I don't use the word 'important.'

That's an advertising or pedagogical word.

VT: I don't use the word 'important.'

That's an advertising or pedagogical word.

BD: Is music getting sucked into the whole advertising trap?

VT: Certainly not! Successful artists and opera companies and orchestras all have a press agent. It's known as a Public Relations position, but they've always had that. You don't sell art like you do children's breakfast food.

BD: Are we not trying to sell popular music the way we sell cereal?

VT: Very probably, but that's not my business. I'm not a merchant nor a provider of popular music. It's an enormous industry. They're very successful, with billions of dollars involved with the various forms of rock and pop. There is little, however, for jazz and black music, which is a very persecuted chamber music. They never put it on the radio and very seldom record it, except on very small labels.

BD: Are you pleased, then, that Porgy and Bess is getting a big revival at the Met?

VT: I don't have to worry about Porgy and Bess. It's a very successful opera. It's been around the world. There's nothing wrong with it and the Metropolitan is perfectly entitled to do it. They could have done it years ago and didn't. Now they are doing it and I do not know how well, but they are doing it. There won't be as much money in it for the Gershwin estate as there was in the tour around the world which lasted three or four years.

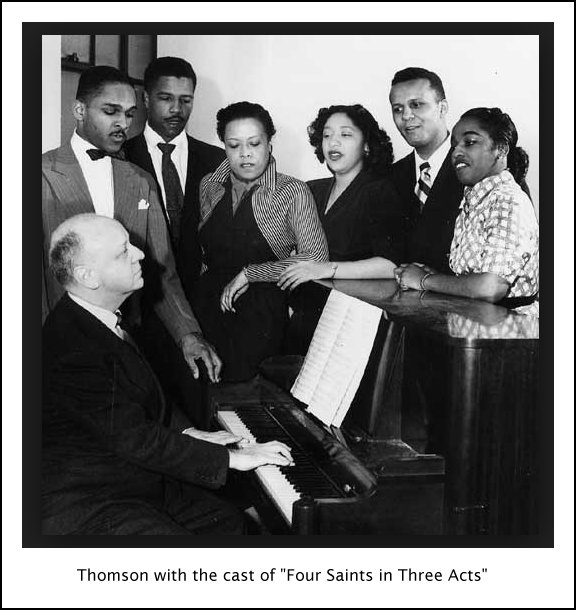

BD: Would a successful production of Porgy at the Met help to get them to do Four Saints in Three Acts?

VT: It might, you never know. Four Saints is difficult to produce because of the obscurity of the text. Stage directors don't know quite what to do with it because they can't understand what the words are saying. On the other hand, the opera of mine called The Mother of Us All, which has had several thousand productions over the last thirty years, goes along comfortably. That works no matter what you do to it. It's fool proof.

BD: Would it even work at a large theater - like

the Met?

BD: Would it even work at a large theater - like

the Met?

VT: No reason why not.

BD: Does opera work in translation.

VT: Some. Depends on how good the translation is. The audience should at least know what the story is because it's quite certain that they won't be hearing all the words.

BD: Whose fault is that - the composer or the performer?

VT: Both. If it is correctly set by the composer, it is easier to articulate. But an awful lot of singers are just vocalizing and not really paying any attention.

BD: So you feel that opera should be more than just vocal pyrotechnics?

VT: I like it that way myself. That doesn't mean that it should be, but I do. The opposite is not vocal pyrotechnics. You can stick on all the scales and arpeggios you want if the language is clear. Scales and arpeggios are an expressive device, not an interference. What interferes with vocalism frequently is over-heavy orchestration, or false treatment of the language from a prosodic point of view. I've looked at operatic scores by dozens of American composers, only a few of which are properly singable. They write instrumental lines and try to make them fit the words, which they don't. Many of the composers have been brought up in families where English is not the domestic language. But the composer had bloody well better know something about the language he's writing in.

BD: And know something about the human voice, too?

VT: (laughing) That we take for granted.

BD: Should we encourage more music to be written?

VT: Sure. We should encourage everything. I encourage everybody to write music the way you want to.

BD: Isn't there any time when it becomes too much?

VT: No. Too much for what?

BD: Too much for us to absorb.

VT: That would be too much for you to absorb. If there's too much for the world to absorb, then it doesn't get absorbed, and that's all right. There's no reason for its not being there. You shouldn't try to stop things just because you have some idea it wouldn't be absorbed. One thing doesn't interfere with another. There's high class stuff, there's middle class stuff and there's low class stuff. There's popular stuff and unpopular stuff and expensive stuff and cheap stuff. There's stuff with enormous financial backing behind it and other stuff with practically none. They're all capable of being first class.

BD: Cheap stuff is capable of being first class?

VT: Anything is capable of being first class if it's well done. Cheapness has nothing wrong with it. An apple can be first class and it's not expensive. The matter of cost - either the cost of production or the cost of purchase - is not a standard for judging quality.

BD: Then why do we as individuals equate quality with cost?

VT: People like to know quality if they can, especially people who live in cities and read newspapers regularly. They get conditioned to the idea that there's a value in quality that extends beyond their consumer ability. People living in the country are not so worried. They know about the quality of the stuff they grow and their neighbors grow, but are not too worried about whether we in the cities are aware of it. We read about it in the papers all the time, not only in the columns, but advertising plays a good deal on our susceptibility of quality. Quality and sex appeal are the big things that they maneuver with.

BD: Speaking of the newspapers, you were for a long time a music critic at the Herald Tribune.

VT: I worked there for fourteen

years and enjoyed it a great deal.

VT: I worked there for fourteen

years and enjoyed it a great deal.

BD: Do you enjoy what you read there today?

VT: I usually take a look at the music reviews to see what the reviewers are up to. I can find out from the advertising pages what the concerts are, but I like to see what the boys are writing. Unfortunately, there is much less music reading in the papers than there is about ballet. Ballet has more space in The New York Times than music does. I'm not awfully interested in ballet, although I used to be and I read about it sometimes. I'm interested in the standards of writing that are observed by these people reviewing things.

BD: So you read them as literature rather than as critique?

VT: Oh, I wouldn't say 'rather than.' I don't limit my interests. I might find a good idea or I might find a bad idea. I might find a good sentence and I might find a bad one. You never know what you're going to find, but I have been among those people for years and I, of course, have been the object of music reviews as well. So it's a department that I look at. In days when I played bridge, I used to read the bridge column, but I don't read it any more because it doesn't have anything to do with the living that I'm doing.

BD: Is it better when a critic is a performer or a composer - as you are?

VT: The best critics have always been the composers. Performers are very dangerous. Composers, and to some extent the historians make legitimate music critics, but you have to be something of a musician. It's a writing job, but the subject is music and you've got to know a good deal about the subject in order to be believable. In order to be a reviewer, you have to forget whether you liked it or not and tell your reader what it was like.

BD: Is there a difference between a critic and a reviewer?

VT: No. Not unless you want to make an artificial distinction - critics write long articles in quarterly magazines and reviewers write short articles in daily papers. I don't think you could hold that up. Criticism and reviewing are synonyms. Not identical, but very close. 'Critic' is just a name they use for it in the paper - it's shorter than 'reviewer.'

* * * * *

BD: Tell me a bit about your last opera, Lord Byron.

VT: He's a good opera subject.

BD: Is it a good opera?

VT: I think so, yes. It hasn't been produced for more than ten years. People are always about to produce the work and they don't get around to it.

BD: You mentioned that the text in Four Saints is obscure. Was that a deliberate device on your part?

VT: At my invitation,

Gertrude Stein, a highly obscure poet wrote a libretto for me. I knew

what I was in for. It turned out that the other one she wrote is not

nearly so obscure. Consequently it travels better. Obscure poetry,

you know, is not non-existent. Many of the most famous poets in the

world are highly obscure; Mallarmé and Rimbaud in French, for instance.

And don't think that among the contemporary poets the very successful John

Ashbury isn't pretty obscure.

VT: At my invitation,

Gertrude Stein, a highly obscure poet wrote a libretto for me. I knew

what I was in for. It turned out that the other one she wrote is not

nearly so obscure. Consequently it travels better. Obscure poetry,

you know, is not non-existent. Many of the most famous poets in the

world are highly obscure; Mallarmé and Rimbaud in French, for instance.

And don't think that among the contemporary poets the very successful John

Ashbury isn't pretty obscure.

BD: But your music isn't obscure!

VT: I don't know about that. That's for other people to find out. You don't try to match collaborators, you try to complement them. A bumpy, troublesome text is better communicated to listeners by a smooth and untroublesome setting. If you match each other, you just throw more grit in the wheels. You don't have to do what your librettist did. You're writing music on the same subject as the libretto. You are not under any obligation, and I hope not even temptation perhaps, to match in one art with an approach which is characteristic of another.

BD: Would you encourage composers to write their own libretti?

VT: Oh no. I think they very rarely succeed. The Wagner operas are a special exception. He was a quite good stage-man and a quite decent German poet. But opera librettos written by their own composer - there wouldn't be half a dozen really good ones. A poor libretto doesn't help the survival quality of any opera. In general, what you might call successful operas - those that remain in the repertory of the big expensive houses over 25, 50, 100, 150 years - mostly have quite good librettos. They depict a situation that human beings like to look at, characters which are interesting, and some kind of structure which moves the whole thing along.

BD: If we have many fine musicians, why do we have so few good libretto writers?

VT: Do you know any college that gives a course in libretto writing? They do in Europe, and they come out a little better than we do, but in France, Germany and Italy, there are professional librettists. They're still around, people who've worked at it and are still capable of avoiding roadblocks. The American academic establishment, the English Lit Department, has no set of models in English literary history which would be worth using to teach a course.

BD: Well, should the academic community provide this kind of training?

VT: If you want to learn something, you announce that you're going to give a course in it. It takes an awful lot of people learning things by trying to teach it before you find out. Certainly the poetry for music and for the stage requires a great deal of three-way experimenting. It's probably best worked out on the practical rather than the academic level. I don't know, but if you want to write operas, you've got to find a libretto, and if you want a libretto, you've got to find somebody that can do it for you. I, myself never used ready-mades. I'd get myself a poet that I could work with and then we'd find a subject that we both liked, and see what happens.

BD: Do you collaborate with the librettist?

VT: Not necessarily. You co-operate. You've got to have a subject that will sustain both of you through the labors of composition. You can't just do this casually, and you can't treat your librettist as if he were a hired-man supposed to furnish you a text for beautiful music.

BD: Do you help in the creation of the libretto?

VT: You do or you don't. It depends on your particular relation. I co-operated much more closely with Jack Larson on Lord Byron than I ever did with Gertrude Stein. We'd agree on a general subject, then she would go to work and write. When it was written she would give it to me and I would go ahead and write music. We could do it that way. Mostly people can't do it that way. The co-operation between Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hoffmansthal was intense and detailed with long correspondence between them which has been published. That's one pair. Gilbert and Sullivan were not so close.

BD: I'm just wondering why that's so rare.

VT: I don't know. Happy marriages are rare, too.

BD: Should there be a line of demarcation between what we call Grand Opera and Light Opera?

VT: You keep asking what should happen. All I know is what does happen. The distinction between Grand Opera, Comic Opera and Light Opera - and beyond that the American Musical - the borders are not utterly precise. These things come about through practice, not because somebody made up an idea.

BD: Do you feel that your music is successful?

VT: Some is and some isn't. I have pieces that rarely get played and others get played all the time. 'Successful' is a term that the publisher would use.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

VT: Look, let us deal

with the present. The world is full of the most expert orchestral performers,

far more than Beethoven ever dreamed of. The world is full of good voices

and some of them know how to sing and some of them can pronounce in certain

languages while singing. Others are not so good at it, but there are

enough singers around to make up personnel at the big houses and even the

college workshops. There are troubles about vocalism as taught and

practiced, but there always have been.

VT: Look, let us deal

with the present. The world is full of the most expert orchestral performers,

far more than Beethoven ever dreamed of. The world is full of good voices

and some of them know how to sing and some of them can pronounce in certain

languages while singing. Others are not so good at it, but there are

enough singers around to make up personnel at the big houses and even the

college workshops. There are troubles about vocalism as taught and

practiced, but there always have been.

BD: And there always will be?

VT: I do not know that. I'm only interested in what takes place, not in anybody's ideas - not even my own - about what I would like to take place. If I go out shopping for dinner, I might think it's too bad that there aren't any persimmons in the market this week, but that's just that. I can't buy what is not in the market and I can't use what is not available and I cannot turn my excellent mind on the analysis of music and its performance except in the form in which it is available. Since I'm not a pedagogue, I'm not teaching people or worrying about the way they are taught.

BD: Can the art of composition be taught, or is it something that just must be learned by doing?

VT: Every school has courses in composition and there are a few ways in which it is approached by pedagogues. There is no history at all of composers getting into the serious concert world or the history books who have not had considerable instruction in the various elements of musical composition, such as harmony, counterpoint, orchestration, fugue, all that kind of thing. There are no ignorant composers getting anywhere.

BD: Are there significant composers who, for some reason, do not get anywhere?

VT: Probably. If they're not getting anywhere, I don't know about them, of course. I do know plenty of excellent composers who are not being wildly successful at selling themselves. Maybe they have no gift for selling themselves or no great interest in it. I've read many operatic scores which I regret are more interesting for their instrumental imagination than their correct and clear relation to the language in which the vocal part is written.

BD: Do you, then, encourage them to write symphonies instead of operas?

VT: I do not encourage anything except what they want to do. If a college pays me, I frequently give a course in all the businesses of how you handle words and music. I'm a little on the antique side to go on doing that these days, but I know a great deal about it and many other people don't. The key to understanding is don't. Don't try to understand. Life goes on with a great deal of water running over the dam and accomplishing nothing. Every now and then a pebble moves.

BD: I want two pebbles to move!

VT: Well, look for 'em.

BD: Thank you for all of the music that you have given to us.

VT: That's all very

nice. I'm the oldest one in the business right now. I presume

that you're interested in my music otherwise you wouldn't be interested by

my music. It holds your attention enough so that you can talk about

it even with me, and you hold my attention for me to scold the hell out of

you about your corny language. Interviewing is a game. We've

had fun.

= = = =

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

= = = =

Bruce Duffie was an announcer/producer with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago for just over 25 years, and his interviews with composers and performers were featured each week. He has also contributed some of those conversations to various publications, including The Opera Journal and New Music Connoisseur.

Visit Bruce Duffie's Personal Website and send him E-Mail.

Linked from New Music Connoisseur Summer, 2002. Next time in this series, a chat with composer Elizabeth Austin.

©Bruce Duffie

= = = =

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

= = = =

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on March 30, 1985.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in November of that year, and again in 1991

and 1996. A copy was also given to the Oral History American Music project

at Yale University. This transcription was linked to New Music Connoisseur Magazine in the

Summer of 2002. It was slightly re-edited and posted on this website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.