A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

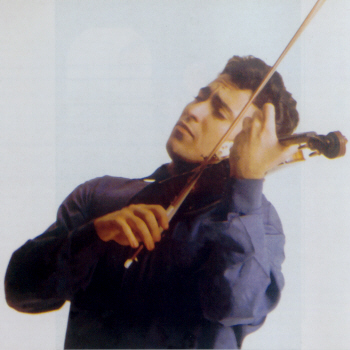

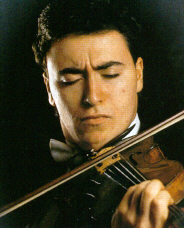

Maxim Vengerov is one of the very few artists who have chosen to play the violin and have risen to the top of the profession. With concert appearances all over the world and recordings of many pieces in his repertoire, he commands attention from both dedicated fans and general audiences.

In Chicago, we've been fortunate to have enjoyed his artistry on several occasions, and he now returns to open the Chicago Symphony's 2001-2002 season. On one of his earlier visits to the Windy City, I had the opportunity to chat with this young virtuoso. His youthful exuberance belied the solid professionalism he already possessed, and he responded to my inquiries with thoughtful directness.

Being originally from Russia but now based in the West, we began

with a comparison.....

Bruce Duffie: Not politically, but musically - how is the West different from the East?

Maxim Vengerov: Everything is different. Each country has a different musical tradition which came from our earliest times. We don't know when it started - just the mentions in the Bible - but it developed in each country in its own way. Every person who likes music... in that way, we are all very much the same.

BD: So all of humanity is united with music?

MV: Yes, but there are different ways of understanding music.

BD: Is there one music, or lots of musics?

MV: Music is one. There are different approaches to music, different interpretations. Even in one school or one country, every artist has his inside-world. Where he studied, where he was born, what influences were upon him, which teachers he had. Even what he listened to and what he liked to do in life. Everything will be an influence.

BD: Without getting into specifics, does politics enter into this, or do you keep politics out of the music?

MV: Of course, I know from my Russian viewpoint, it was always separate. Our life is music and politics has not touched it. What is interesting is that music is one language. We may speak Russian, English, French, etc., but music is one language, and if we are to understand it, it's up to the artists to deliver this language in a manner that everybody can understand.

BD: So it's the responsibility of the performer?

MV: Of course. And also the composer.

BD: Is it the responsibility of the audience to come prepared for your concerts?

MV: I wouldn't think so. The artist has to prepare the audience by the way he goes on the stage, by the way he touches the first note, the way he lifts the bow or puts his hands on the piano. Also, the way he looks at the audience. We should prepare the audience in that moment before we start to play.

BD: You play "classical" music or "concert" music. Is this kind of music for everyone?

MV: Everybody tries, but not everybody can succeed. It also depends on what point we want to hit. It's very much up to the artist.

BD:

As the artist, do you feel you're collaborating directly with the

composer?

BD:

As the artist, do you feel you're collaborating directly with the

composer?

MV: The composer writes his work for a certain instrument and he means it to be understandable for the performer. So, the performer can deliver what he means. It could be a different approach from the composer, but we have to think about what he thought and why he wrote it. But we have to deliver it our way. We shouldn't repeat, but we must try to play the way they wanted it. We have to produce our own sounds and our own interpretation, but we have to listen to the ideas of the composer. Those are written in the music for us to see.

BD: Is everything on the page, or is some of it in your heart?

MV: He puts his heart onto the page to help the music to be delivered to the audience.

BD: So how much is the composer and how much is Maxim Vengerov?

MV: I wouldn't separate them or make them together. When I play, I play my music and I play music of certain composers. I don't want people to say they're not going to listen to the composer but only to Vengerov. I try to understand each work as it's written and I try to deliver as much as I can. I want to get all possibilities out of the music.

BD: So it's up to you, as the performer, to bring it to life?

MV: Sure.

BD: Do you feel you're part of a lineage of performers?

MV: Actually, we are. We are all different, but you cannot run away from it. It is interesting to look at everything that has been done before. That's true in every profession. If you're in technology or if you're a teacher, you have to look at what was done before. Then you have to make your own decision and have your own approach to what you want to do.

BD: Learn from the past and then go out on your own.

MV: Sure.

* * * * *

BD: There's been so much written for the violin. How do you decide which pieces you will select and which you'll not work on right now?

MV: First of all, I only play what I like to play. I never play works that I don't like - there's no sense in that.

BD:

So how do you decide whether you like it or not?

BD:

So how do you decide whether you like it or not?

MV: There are some pieces which are not close to your heart, but you like them and you want to kill them in order to understand them. But I have some limitations, even though I get asked for this or that piece.

BD: So you must decide "yes" or "no."

MV: It's very simple. I'm not very conservative in choosing the music I play. In my opinion, the music has to have sense for me to play it. If it has no sense, I wouldn't agree to play it. Maybe it has a sense, but I don't understand it, and if I don't understand, then my audience won't, either. It doesn't mean anything if I play a piece that I don't like. Perhaps in a few years, I will understand it. But so far, I play everything!

BD: How do you divide your career between recitals with piano and concertos with orchestra?

MV: They're quite separate. I play a lot of recitals. I have a wonderful pianist who is my partner, Itamar Golan, and we're doing a lot of chamber music now. Otherwise, I am doing my concerts, and he does concerts with other people. He wants to play only chamber music, not solo. It gives me a lot of pleasure to perform on the stage, just the two of us.

BD: When you're playing, are you conscious of the audience that is there in front of you?

MV: I am part of the audience. I listen. I don't like to be the kind of man who only performs for an audience. I play for myself, also. I have a feeling that I'm outside my body, going around the audience listening, and that is very helpful. If I play for an audience, I should know what they hear, not only what I hear. What I hear in my ear is completely different from what the audience hears. It takes great art to understand and to hear from outside.

BD: Are you pleased when you hear yourself?

MV: Not always. I am very self-critical. If one says that a concert was perfect, then you cannot grow any more and you have no more to say. You must stop because you're lost.

BD: Is perfection even attainable?

MV: No, but only because I make another level. Each time I go onto the stage, it's like a sport and I set the bar a bit higher. I move it up and up and I never hit it. There is always more to be discovered.

BD: Have the composers done that for you? Have they put more and more in their music?

MV: It's the kind of repertoire I choose now - it's a very serious repertoire. And it's not only the repertoire. When you play a work for the first time, you have to hit your maximum. Or you are surprised and you play better than you thought you could. Then you aim even higher, so you have a lot to grow into. There is no limit.

BD: Are there times, perhaps even in performance, that you discover something new?

MV: Only in performance, and mostly in the solo concerts. Mostly, I practice only with my brain and do the technical points. When you perform, you see how it goes.

BD: Do you adjust your technique for a smaller house or larger house?

MV: Of course. You have to do that. If you play in a large hall the way you do in a small room, nobody could hear - not only the sound, but the dynamics and the approach. You can do an interpretation at home in a small room, and onstage you see it's not good enough. You must adjust all the time. You may never play in one hall the same as you do in another. With one orchestra or another, with one pianist or another. You adjust to the orchestra or the pianist and to the audience. You play for each audience differently. Also, your mood is changing and you react to the weather. Rain, or snow will affect my feeling and my life. Everything is an influence on my playing.

BD:

What about recordings - do you play differently for the microphone?

BD:

What about recordings - do you play differently for the microphone?

MV: It's different, but it's great art to understand what recording is. It's not easy to stand in front of the microphone and do several 'takes' for this metal object. Sometimes I see it as a person standing in front of me.

BD: An ideal person?

MV: Ideal, yes. I ask my producer to applaud me before I start to play. When we recorded the Mozart Sonata, we had a good portion and had several takes, and I suggested we run it straight through. It doesn't bring life into the music if you do too many separate pieces and splice them together. So we played it through as a concert, and I asked the producer and my mother and the engineer to applaud just as a concert. We bowed and played the whole movement, and it was surprising because it was something new for us. There was a live-ness. When you stop, you lose the tempo. Not necessarily the actual speed, but the feeling. When you play straight through and imagine the audience in front of you, you play differently. We were only going to do the first movement, but the producer said to continue just as a concert. It was very helpful, and there were not many splices for corrections.

BD: Are you pleased with the various recordings you've made?

MV: I'm never very pleased with what I've done because

it's

in the past. I've progressed beyond that now. On the other hand, I'm

pleased

with what has been done, but I don't want to play that way now. I try

to

look always at the future.

* * * * *

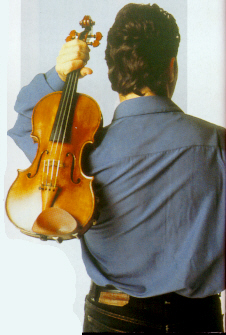

BD: Tell me about your instrument.

MV: To choose an instrument is like to marry someone, to live with somebody. Even with a good instrument, sometimes you just cannot live with each other. Your heart and the violin's character aren't suited to each other. You never come together. That is the big problem. Another problem is the financial level.

BD:

Are the violins which are priced at millions of dollars worth those

millions

of dollars?

BD:

Are the violins which are priced at millions of dollars worth those

millions

of dollars?

MV: Sometimes yes. It's difficult to decide which price is really correct.

BD: Do you practice on the best instruments, or just save them for the concerts?

MV: Sometimes I practice on a lesser- instrument. Then, when I play the concert, I get the jump up by playing the wonderful one.

BD: Does it give you a secure feeling to be booked years in advance?

MV: I feel secure that I have job. I won't be hungry and I'll have the opportunity to play for audiences. Each time I play in front of people, I enjoy it. That's my life. I couldn't imagine not playing the violin.

BD: Are the audiences different in cities across the world?

MV: Very much different in tradition and temperament. It does influence me, but I don't heed people who say that maybe this one is more conservative and I must be careful. I play any program I want in any location, and try to convince them that the program has sense.

BD: Do you like all the travel?

MV: It's tiring, but it's worth it.

- - - - -

= = = = = = =

- - - - -

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 18, 1993.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following

year,

and again in 1999; and on WNUR in 2003 and 2006.

This transcription was made in 2001, and posted on this

website

at that time. The link was used by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

beginning in August of 2001.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.