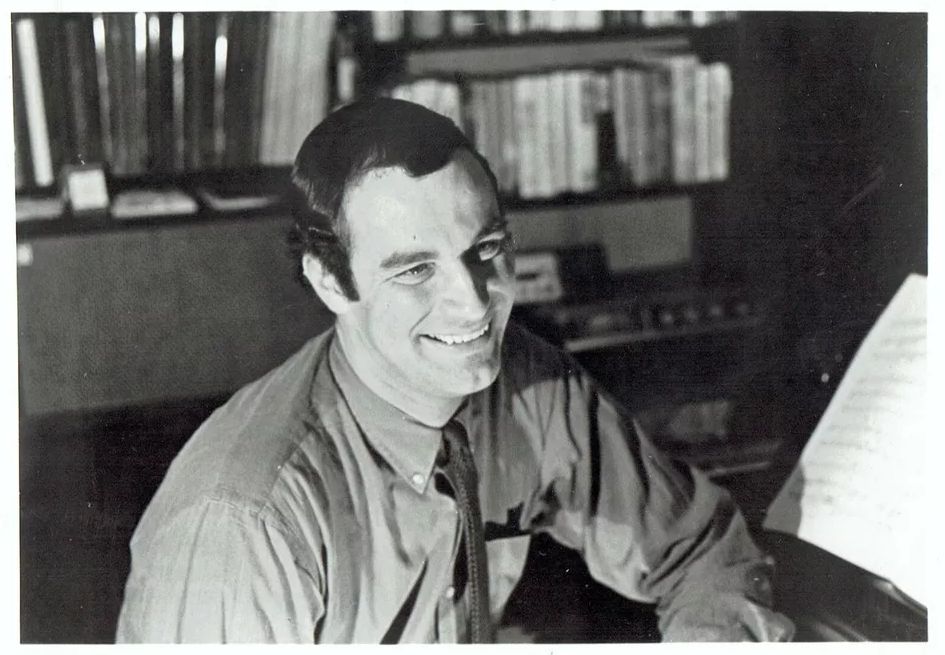

[This photo from 1974, as well as the production photos below, are courtesy of the Seattle Opera]

|

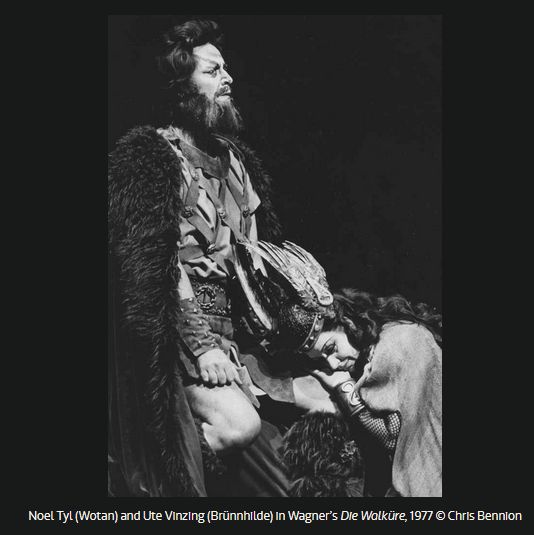

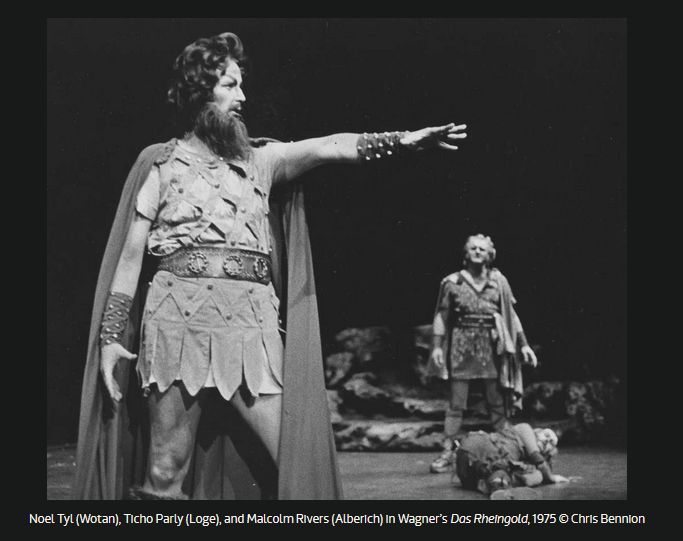

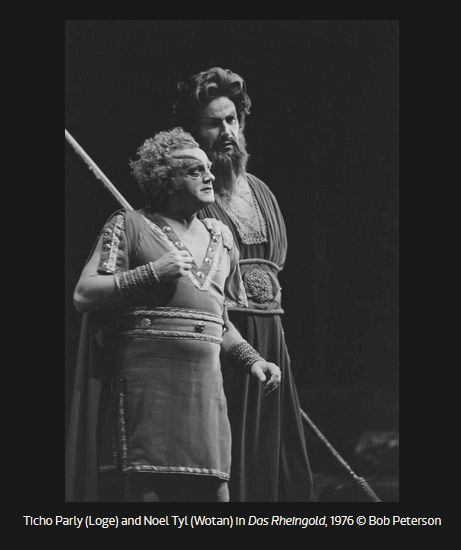

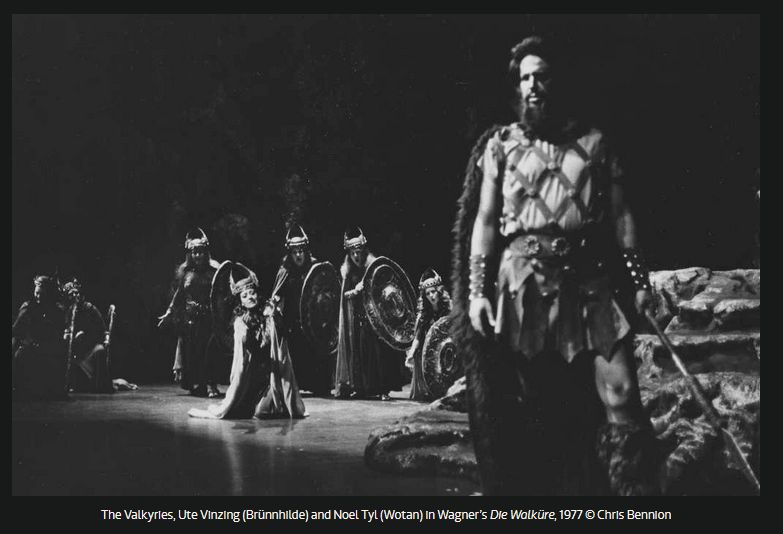

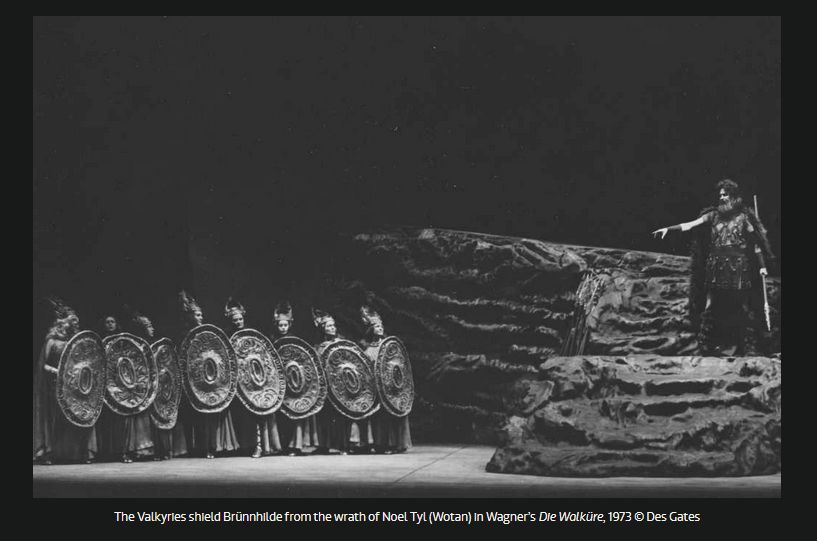

Tyl was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and graduated from Harvard University in social relations (psychology, sociology, and anthropology) in 1958. He had studied singing and piano at school, and as a freshman at Harvard joined the Harvard Glee Club. Two years later, he was elected its manager. While at Harvard he also sang in the Harvard Opera Guild’s first production, The Barber of Seville. After graduation he moved to Texas where he worked as the business manager of Houston Grand Opera and continued his voice studies. He then moved to New York City for further voice studies while simultaneously working as a public relations executive. In 1964 Tyl won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions and shortly thereafter commenced a full-time opera career. Over the next twenty years he appeared in many American opera houses, including New York City Opera, Cincinnati Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Seattle Opera, and Washington Opera, as well as appearing regularly with the Vienna State Opera and the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf. He initially sang bass roles, but in 1970 expanded into the bass-baritone repertoire and found a particular affinity with Wagnerian roles such as Hans Sachs (Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg), Wotan (Der Ring des Nibelungen), and The Dutchman (The Flying Dutchman). Tyl had retired from the opera stage by the late 1970s and returned to public relations after founding the Washington, D.C.-based firm Tyl Associates. However, he came out of retirement in 1981 to appear in two productions (Madama Butterfly and Semele) with Washington Opera and in 1987 sang in a live German radio broadcast of Kurt Weill’s cantata, Ballad of the Magna Carta. Earlier in 1987, he had given a benefit solo recital for the McLean Choral Society. Among the pieces on the program were two of his own compositions, a setting of Longfellow’s poem "The Children’s Hour" and A Rudhyar Suite: Sunset, Truth, Rebirth, Awareness which was set to texts by the astrologer, composer, and poet Dane Rudhyar. By the late 1960s, Tyl had developed an interest in astrology and its relationship to human psychology, particularly need theory. Astrology became his parallel profession for many years, and since his retirement from Tyl Associates was his sole profession. His first book, The Horoscope as Identity, was published in 1973 by Llewellyn Publications and began his long association with that publisher. A twelve-volume series The Principles and Practice of Astrology soon followed and over the years he became the company’s most published author. His Synthesis and Counseling In Astrology, a 1000-page professional manual on the use of astrology in counseling, was published in 1994. That same year, he moved to Fountain Hills, Arizona, where he continued to work as a consulting astrologer as well as teaching, lecturing and writing on the subject. At the 1998 United Astrology Congress, the world convention for astrology, he received the Regulus Award for "establishing and maintaining a professional image in the field." His 2001 Solar Arcs: Astrology’s Most Successful Predictive System contains autobiographical material in relation to his own horoscope. |

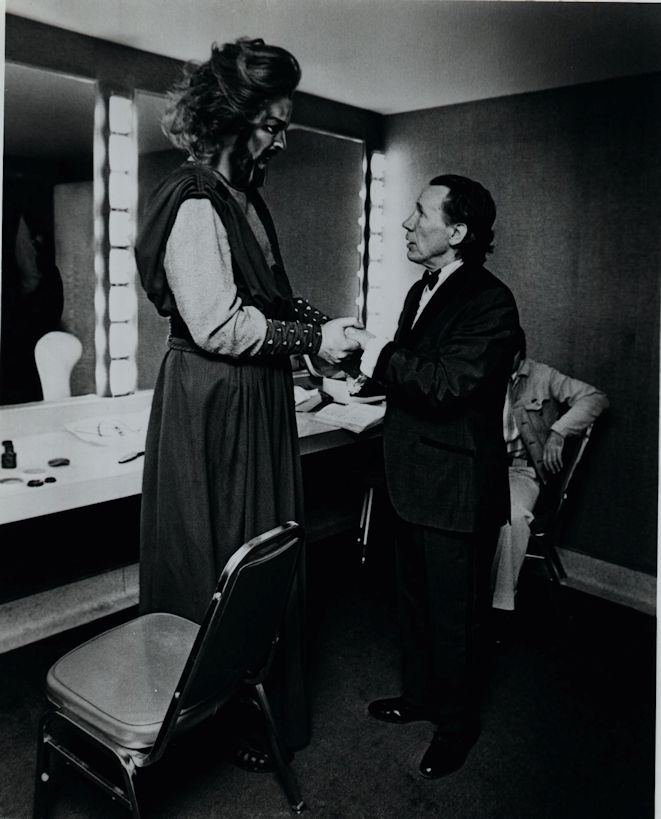

© 1980 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in the studios of WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago on October 6, 1980. A large portion was published in Wagner News later that month. This full transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.