Pianist Alexander Toradze

A conversation with Bruce Duffie

Pianist Alexander Toradze

A conversation with Bruce Duffie

Alexander Toradze is universally recognized as a masterful virtuoso in the grand Romantic tradition. He has enriched the Great Russian pianistic heritage with his own unorthodox interpretative conceptions, deeply poetic lyricism, and intensely emotional excitement.

Born in Tbilisi, Georgia, Alexander Toradze graduated in 1978 from the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow and soon became a professor there. In 1983, he moved permanently to the United States and gave many solo concerts and appeared with many orchestras and distinguished conductors.

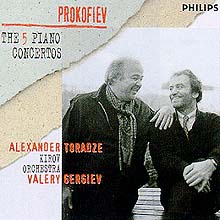

Though few in number, his recordings have been significant. Toradze's recent set of all five Prokofiev Piano Concertos with Valery Gergiev and the Kirov Orchestra for the Philips label, is acclaimed by critics as definitive. In it, Concerto No. 3 is named by the prestigious International Piano Quarterly as "historically the best on record" (from among over 70 recordings). Other highly successful discs have included recital albums of the works of Mussorgsky, Stravinsky, Ravel and Prokofiev for the Angel/EMI label.

Besides his demanding performance schedule, Toradze has taken the time to pass along his knowledge and insights to the next generation of pianists. In 1991, he was appointed the Martin Endowed Professor at Indiana University South Bend, and has created a teaching environment that is unparalleled in its unique concept. The members of the multinational Toradze Piano Studio have developed into a worldwide touring ensemble that has gathered great critical acclaim on an international level.

Though he is practically a neighbor, each appearance in Chicagoland is a special event. Returning on February 17th, Toradze will play the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto #1 with the Northbrook Symphony, conducted by Lawrence Rapchak.

It was on one of his previous trips to Chicago that I had the pleasure

of chatting with Alexander Toradze at the WNIB studios. Here is much

of that conversation . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Let me first ask - how do you divide your playing between solo recitals and concerto repertoire?

Alexander Toradze: Approximately 75% are orchestral and the rest are solo recitals. When you come into a town for the first time, I think it's more appropriate to play with orchestras so the public will get to know you. Then, if you have luck and success, you can return and have an audience for solo recitals.

BD: Do you play differently when you are the only attraction, as opposed to when you're part of an orchestral concert?

AT: I don't think I play differently. It's certainly different

music, but my preparation and psychological focus on the concert is quite

similar. However, when you play a recital, the focus will be divided

toward several pieces. Sometimes it's three or four, sometimes even

more than that, but when you play a concerto, the focus is on just that one

particular piece. The psychology will be different when I'm playing

the Brahms B-flat or a Lizst concerto or the Prokofiev 1st. But still,

with the orchestra your direction is focused on just one piece. However,

things are more complicated with orchestra because of rehearsals, and because

of the relationship between you and the conductor. That's a very important

thing, as well as the relationship between you and the orchestra itself.

You could have a wonderful relationship with the conductor but the orchestra

might not particularly enjoy playing with you, or vice-versa. Usually,

however, when I play with an orchestra and its music director, it affects

the relationship and the orchestra likes it, too. It's not a complication,

but the steps you go through in preparation for the concert have their own

details.

AT: I don't think I play differently. It's certainly different

music, but my preparation and psychological focus on the concert is quite

similar. However, when you play a recital, the focus will be divided

toward several pieces. Sometimes it's three or four, sometimes even

more than that, but when you play a concerto, the focus is on just that one

particular piece. The psychology will be different when I'm playing

the Brahms B-flat or a Lizst concerto or the Prokofiev 1st. But still,

with the orchestra your direction is focused on just one piece. However,

things are more complicated with orchestra because of rehearsals, and because

of the relationship between you and the conductor. That's a very important

thing, as well as the relationship between you and the orchestra itself.

You could have a wonderful relationship with the conductor but the orchestra

might not particularly enjoy playing with you, or vice-versa. Usually,

however, when I play with an orchestra and its music director, it affects

the relationship and the orchestra likes it, too. It's not a complication,

but the steps you go through in preparation for the concert have their own

details.

BD: Do you get enough time to rehearse with the orchestra before each concert?

AT: Sometimes, yes. Most of the times, no. You're lucky if you get one rehearsal plus the dress rehearsal. More often, it's one rehearsal only. In Russia and the Eastern-block, from which I ran, are much more generous with rehearsals because there are fewer union problems and fewer restrictions with time.

BD: Are the orchestras here in the West more used to it, so they're geared to doing things better and faster?

AT: Faster doesn't always mean better. Sometimes it does, but usually it doesn't. However, I'm against over-rehearsing anything, including my own practicing. Something should be left to discover on the spot in the concert. That's very important, I think. I will never forget a situation when I was on tour with the London Symphony, conducted by Rostropovich. We were in Pompeii doing the Tchaikovsky 1st. It's tricky, especially at the end when you have to feel the orchestra and feel the conductor and know the tempos and what kind of drive you have.

BD: It all has to be coordinated.

AT: Yes, and when we came to the coda, the last page-and-a-half or two pages, which is maybe 35 seconds of music, the orchestra stopped playing. I turned to Slava and asked what was happening and he said, "We cannot rehearse any more because the time is up." The orchestra didn't even ask anything. They just stopped, stood up and left. My jaw dropped to the pedals and I was dumfounded. It took about a half hour to get myself together because of the shock that musicians would behave this way, but I eventually saw that they were right. It was probably my fault for having asked to repeat something earlier in the session, so we didn't have time to finish the piece.

BD: So now you've learned to budget your time better?

AT: I suppose. I just spoke with a friend, pianist Vladimir Viardo, and he had the very same experience with the Rachmaninoff 3rd Concerto. Just a page-and-a-half left and the orchestra stopped. He couldn't understand why, just out of respect for Rachmaninoff, they didn't finish it. So these are the kind of restrictions you have.

BD: I can understand them not going on to another movement or further rehearsal, but not to finish the phrase.....

AT: But when you think of the tremendous stress and pressure there is on orchestras today, with all the programs they have and how many guest soloists there are and the number of great conductors, they cannot do extra just for some and not for everyone. They have to have rules which they follow every time. It can be ironic, but it happens, so what can you do? These are the circumstances when you deal with orchestral concerts. When it's a solo recital, of course, you can practice as much as you wish. I used to get a piano in my hotel room, but you're not alone in the hotel. Your neighbors are there and send sweet letters saying how much they love the playing, but they came into town to do business very early in the morning and they have to get some sleep. So please don't take it personally, but please......... So I stopped getting a piano in the hotel room.

BD: What kind of pianos do you get when you're a guest on tour?

AT: Occasionally I will have an instrument of my choosing from Steinway's basement, but only if it's in or close to New York City. Elsewhere, the local Steinway dealership will be cooperative and send a piano. Many auditoriums will have their own piano and the technician will work on it for me.

BD: Do you find you're able to work with whatever piano is provided?

AT: That always is a question. You never know. You

go to the hall and open the piano and you never know what you're getting.

However, it's an equal situation because the piano doesn't know what it's

getting, either! It's a nice equilibrium. You take what you get

and do the best you can, and, obviously, the piano does the same. It

operates the best it can with your fingers. When I first came to America,

I expected it to be 1000% perfect and 999% wasn't good enough. But

it couldn't get better. Nothing could. So I wasted my time and

others', too. In Russia, I would play many times on pianos with broken

strings or broken keys. Many times I would have to put a piece of rubber

in-between strings so they wouldn't sound. It's a pitiful situation.

AT: That always is a question. You never know. You

go to the hall and open the piano and you never know what you're getting.

However, it's an equal situation because the piano doesn't know what it's

getting, either! It's a nice equilibrium. You take what you get

and do the best you can, and, obviously, the piano does the same. It

operates the best it can with your fingers. When I first came to America,

I expected it to be 1000% perfect and 999% wasn't good enough. But

it couldn't get better. Nothing could. So I wasted my time and

others', too. In Russia, I would play many times on pianos with broken

strings or broken keys. Many times I would have to put a piece of rubber

in-between strings so they wouldn't sound. It's a pitiful situation.

BD: An 85-key piano!

AT: You're lucky if you got that! I would frequently have to play big concerts on upright pianos. I don't want you to hear irony in my voice. It was a pain! Such a rich country with phenomenal culture, but good pianos (which are not simple things) don't exist unless you're in a major hall in a major town.

BD: There's an old joke about the pianist who sits down to play, adjusts the stool, calls for a book, sits on the book, removes one single page, re-sits and is finally happy and begins the concert.

AT: You laugh, but it can be very true. Not a page, but a quarter-inch can be very disturbing. I've had poor chairs and it's worth going and getting a different one. It's a hassle. Some pianists will travel with their own chairs. Over the years, I've had problems with chairs, and stagehands would try to be as accommodating as possible, putting a little platform underneath, but that was not attractive.

BD: Perhaps take an inch off each leg of the Steinway?

AT: To make the piano lower? I see! (Laughter) They put the pianos on big wheels so they're easier to move, and that adds height.

BD: Does there come a time when you're in front of the piano and the audience is waiting, so you just have to give the best you can no matter what you've got to work with?

AT: Oh yes. That happens in every profession, and with pianists as well. There are times when the piano is not well, or you are not well, but you go on anyway.

BD: But you don't suffer like a singer would because of a bad throat, do you?

AT: The vocal cords are the most delicate and sophisticated instrument, and the most precious. However, fingers have their own problems and we are all performers, so we must consider the affect. You are performing when you speak on the microphone, and I am performing when I'm playing for the audience. A similar type of concentration is involved.

BD: Is it art, or is it entertainment?

AT: I think it's both.

BD: Then where is the balance?

AT: In different cultures there are different balances, and inside different cultures, different artists have different balances. It's very hard to make a global analysis of that problem because we cannot even scratch the surface. In a very interesting way, Russian music is extremely entertaining, besides being very dramatic and certainly very deep because it deals with deep and powerful emotions of the human being and the history of the Russian people. Their folk music is also very moving and the religious songs are extremely interesting and precious. At the same time I think that Russian music is among the most entertaining, perhaps because of the combination of all that I've just mentioned. Some of the musicians think that Russian music can be very decorative, and because of that it's less pure. In my opinion, Russian music has no less right to be called Pure Art than any other music. I think American concert-goers appreciate both the artistic showmanship and musical intelligence of the performer, and that comes from knowing a lot. I think American listeners are very well aware of what they're hearing and why they're listening - thanks to you and other radio stations, thanks to TV, and mostly thanks to all this stereo equipment which has been around for a long time.

BD: When you're playing a concert, do you feel you're competing against all the recordings that have been made of that piece?

AT: No, I never have that in mind. I would never be able to play better than those old recordings. Those artists have their own place in history and I can't compete with history. I want to be myself as much as possible, not because I think it's the best way to play the music, but it's the best language I know. It's my language. It might be interesting for you or not, but that's what I feel comfortable to play. I'm competing with myself. I play my own interpretations. Subconscious and conscious memory are keeping a chart of what I've done with this piece in previous performances. I don't want to repeat. I'm not in a position to think that there is only one truth for interpreting a work. There are so many aspects of the truth. Something can be said one way or another way...

BD: So every time you play, you're discovering another one of those truths?

AT: Exactly. And every time is the truth, ironic as that may seem. This is where music starts to be ‘art' for me. Living with these creations is how I am.

BD: Cutting through all of this, what, for you, is the purpose of music?

AT: I only can answer that in terms of what music is for me right now. Yesterday it was different. Two years ago, five years ago, it was different. Every time, it changes. I'm not trying to stonewall the question or the idea, because your question is very deep and needs focus. But years ago, the purpose of music for me was to have a chance to go abroad and see the world and play in places where I dreamed I'd play in my childhood.

BD: So it was a vehicle, then.

AT: Actually, music is a vehicle, in a way. Music is a vehicle

in getting to know yourself and getting to know the world. So is literature,

so is radio, so is talk. We are learning about ourselves and communicating.

I think that's the right track to follow - communication. A common language

is necessary. Within this music, this form of classical piano playing,

you need to find your own language which, hopefully, will be understandable

by others who have already learned that language by listening to lots of

it. They should accept your language. That barrier is not easy

to overcome, because you have people with their own interpretation in mind

from the greatest performers. They're not willing to re-learn the piece

just because you've come up with some stupid or crazy idea. It's your

idea and that's why it's valid, but it is different and requires so much

strength from the other party to understand you. Earlier today, I was

sitting in the empty hall, practicing and getting to know the acoustics and

the instrument, and I realized that these pieces I will play are like friends.

They have helped me find my way and have traveled with me to so many places.

So I must try to put those experiences we've had together and show them.

Maybe someone will catch the atmosphere which we are trying to create.

I'm saying ‘we' because I'm playing them no less than they are playing me.

We're at that stage in our relationship. They have their own way with

me. They kind of own me and manipulate me. It's very fascinating.

AT: Actually, music is a vehicle, in a way. Music is a vehicle

in getting to know yourself and getting to know the world. So is literature,

so is radio, so is talk. We are learning about ourselves and communicating.

I think that's the right track to follow - communication. A common language

is necessary. Within this music, this form of classical piano playing,

you need to find your own language which, hopefully, will be understandable

by others who have already learned that language by listening to lots of

it. They should accept your language. That barrier is not easy

to overcome, because you have people with their own interpretation in mind

from the greatest performers. They're not willing to re-learn the piece

just because you've come up with some stupid or crazy idea. It's your

idea and that's why it's valid, but it is different and requires so much

strength from the other party to understand you. Earlier today, I was

sitting in the empty hall, practicing and getting to know the acoustics and

the instrument, and I realized that these pieces I will play are like friends.

They have helped me find my way and have traveled with me to so many places.

So I must try to put those experiences we've had together and show them.

Maybe someone will catch the atmosphere which we are trying to create.

I'm saying ‘we' because I'm playing them no less than they are playing me.

We're at that stage in our relationship. They have their own way with

me. They kind of own me and manipulate me. It's very fascinating.

BD: With this huge repertoire to choose from, how do you decide what you'll play now and what you'll postpone until later in your career?

AT: Now we're entering a very interesting subject of scheduling a whole season, and what comes after what and why you want to put this or that program here or there. The basic idea is to do as much as you think you can do your best and frame your repertoire during the year. That should be your main guidance. So if you're just playing a lot of music to show off how much you can do, I'm not that kind of sportsman. I'm very much for different repertoire and a growing repertoire because I believe that we grow when we try new pieces. They give you new thinking-ability.

BD: Standard pieces which are new to you, or brand new works?

AT: Both! A brand new piece is, nowadays, such a rarity that it's a subject which is almost forbidden. Where are they? And who should feel guilty about that? Performers or composers? Maybe composers. Maybe performers. Great operas are written for great singers, but which is first the egg or the chicken? The same thing is true for us.

BD: There are many great pianists. Why isn't more being written and played?

AT: Maybe we need a kind of alertness to inspire composers.

Maybe something is lacking because my father was a composer. He was

a powerful pianist with a huge hand and technique. Only his very last

piece was a piano work. It took enormous effort on my part to get this

concerto out of him. I made him do it, and after giving me life, this

was the best present he left me.

* * * * *

BD: Is music political?

AT: It can be.

BD: Should it be?

AT: There are times when it probably should be. Music and musicians are inseparable, so if we say that music shouldn't be political, then we're saying that musicians could not or should not be political. That is just not true. There are times when you have to have political sense. I don't mean local or small things, but big battles for more freedoms and more free spirit and open communication. That's what kind of politics I mean - not the kind where you're associated with one group against another group. It's always around us, but that's secondary. I'm not putting myself on a pedestal, but in many ways, people like myself make a political statement by moving and leaving their lives behind and coming to a new country. It has been done before by many great musicians and others, and I think that contributes to whatever is going on today in Russia. One drop and another drop and a hundred drops and then the cup is filled and something happens. I'm not saying that musicians' behavior in the last few years was the main stimulation for what is going on today, but our contribution is great. I'm very proud of that. Without realizing just what is waiting for us, we picked up and left. It would be naive for anyone to assume there would be a position to have and enjoy on the other side. There is always risk. Even now, when things are much more open between East and West, they are still leaving.

BD: It has worked out well for you.

AT: I feel myself very lucky and privileged. I'm doing what I want to do and pursuing what I want to pursue, and leading a very full life. But it cost me a tremendous amount of effort to achieve that situation. It's not a feeling of self-satisfaction, but a feeling that you are doing something right. It's positive, and that feeling comes within you, not because of things surrounding you. America has taught me to try to be happy in the situation where you are today and not look at what I should have done differently yesterday. Mistakes will remind you what you shouldn't do, but to learn how to find happiness is the lesson.

BD: Getting back to music, do you like being a wandering minstrel?

AT: Yes. I love it. Most of the places where I go now

are ones I've been several times, and I know the spots which I love - hotels

and restaurants that I enjoy with friends, and museums. It gives me

the opportunity to see the world and meet people. Each town dictates

its own rhythm on you, and I love rhythm. Without rhythm, music wouldn't

exist. I like the changes of each town's heartbeat. Countries,

too, for that matter. Besides the driving rhythm, there are so many

poly-rhythmic things that are characteristic of each place. When I

was able to bring my mother here to be part of my family, I was proud to

show her ‘my' America. It was like when I showed my native Georgia to

foreigners when they would come, the same things are happening here.

AT: Yes. I love it. Most of the places where I go now

are ones I've been several times, and I know the spots which I love - hotels

and restaurants that I enjoy with friends, and museums. It gives me

the opportunity to see the world and meet people. Each town dictates

its own rhythm on you, and I love rhythm. Without rhythm, music wouldn't

exist. I like the changes of each town's heartbeat. Countries,

too, for that matter. Besides the driving rhythm, there are so many

poly-rhythmic things that are characteristic of each place. When I

was able to bring my mother here to be part of my family, I was proud to

show her ‘my' America. It was like when I showed my native Georgia to

foreigners when they would come, the same things are happening here.

BD: You mentioned that your father was a composer. What advice do you have for a composer who would write a sonata or concerto for you, or for any pianist?

AT: In my view, you have to have a performer in mind. The same piano can sound very different under different fingers, so it's not just singers who have their own ‘sound,' but pianists, too. It's very important for the composer to have this image of sound - the sonority - of the performer for whom he's writing, plus the agility and abilities of the technique to create for that particular pianist. If you see the literature, many great pieces were created with a particular pianist in mind. It's the same for conductors - composers create symphonies for a particular conductor. It's very important to have that person, and you feel his body movements for the sound. You feel his face and what kind of moment this person will create taking this chord or this theme. If someone was to write for me, they have to like what I'm doing and how I'm doing it. It's very hard to write in the abstract for someone who will someday play this piece.

BD: What advice do you have for younger pianists coming along?

AT: Besides the famous cab-driver joke of how to get to Carnegie

Hall, in this time when more and more becomes business and more business and

sometimes only business, I would like for colleagues to keep inside the spiritual

aspect of performance. Don't forget to pray to God before each performance

and don't forget to give your soul enough air. Believe in the right

purpose of art and believe in being human.

= = = = = = =

- - - - -

= = = = = = =

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 24, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, 1994, and 1997. This transcription was made in 2002, and was given to the Northbrook Symphony for use on their website beginning that January. It was also posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.