|

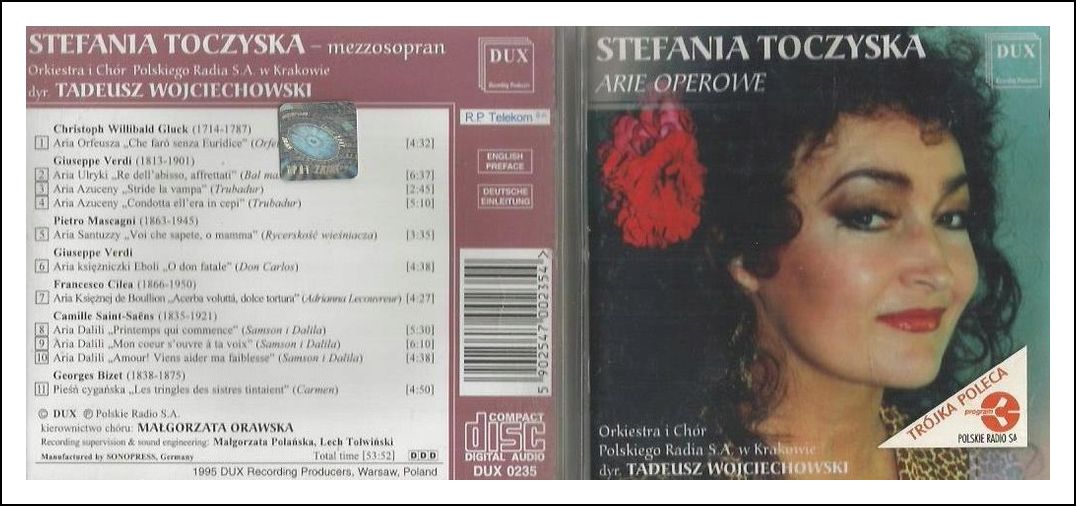

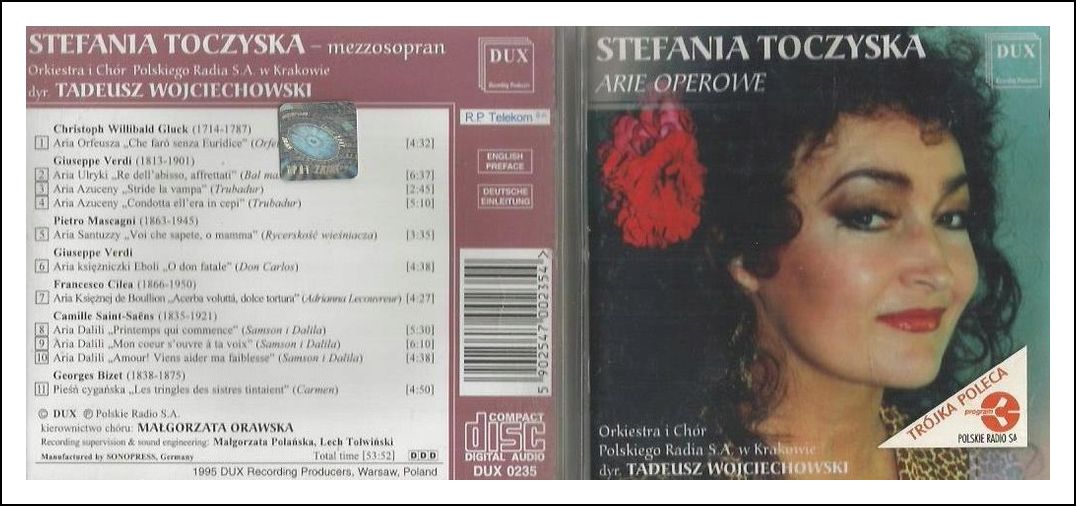

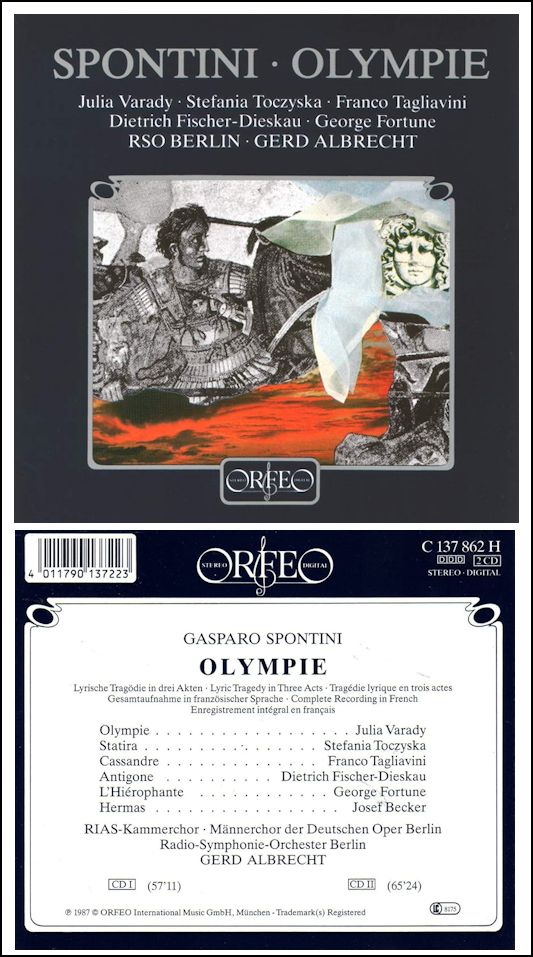

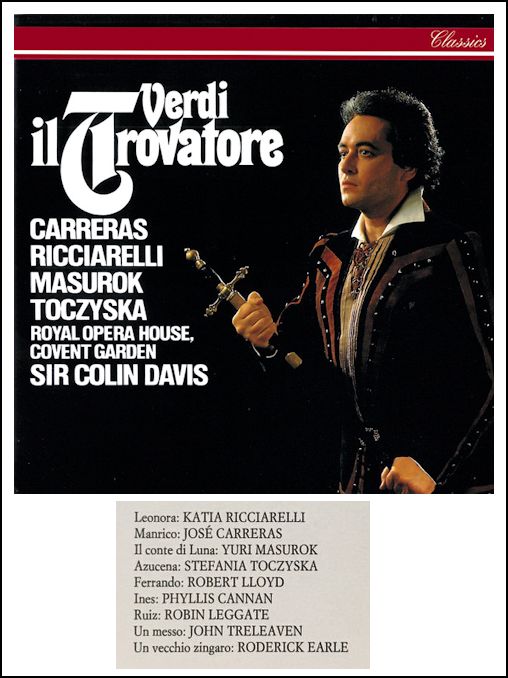

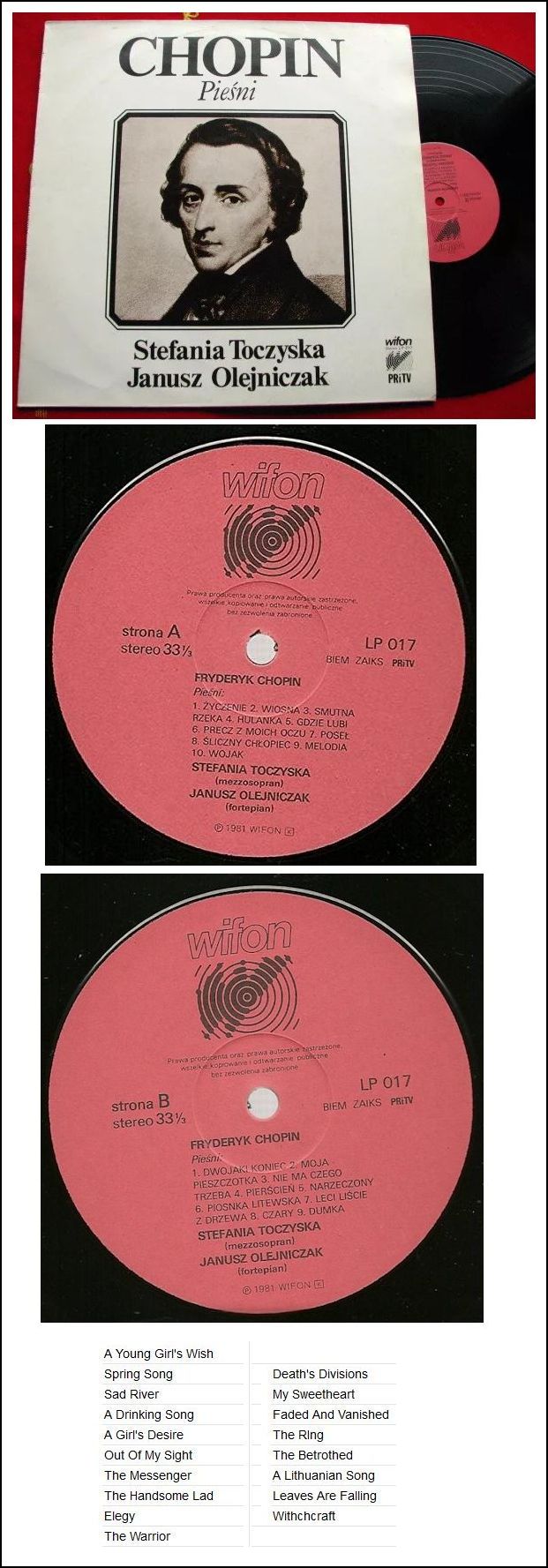

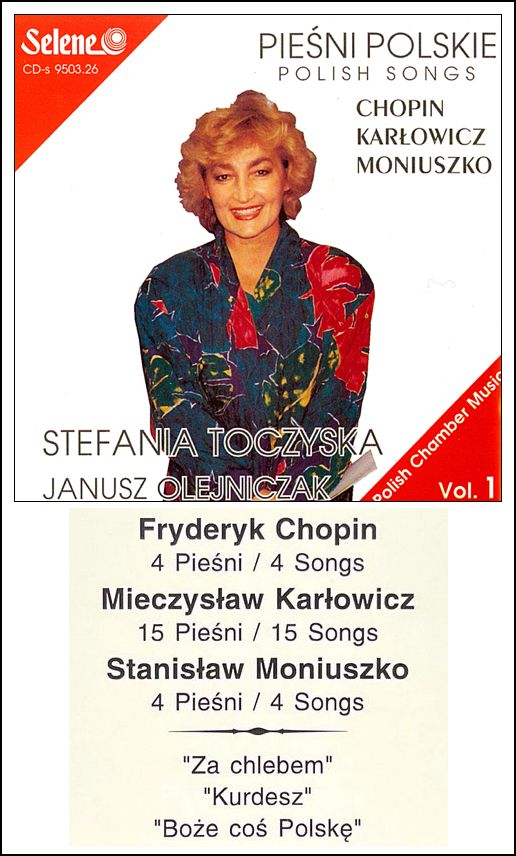

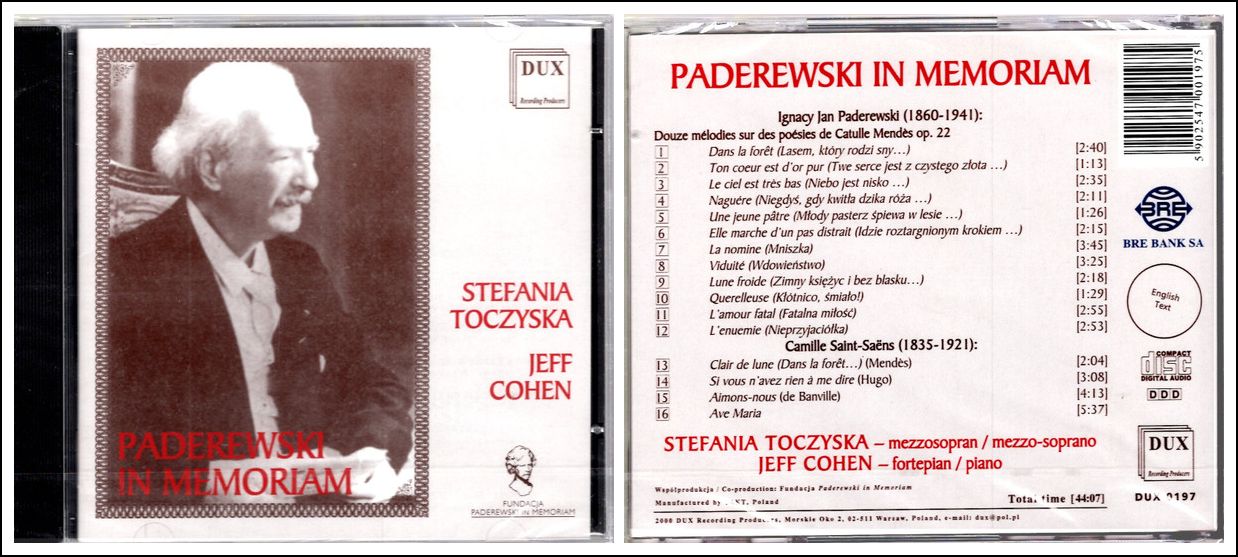

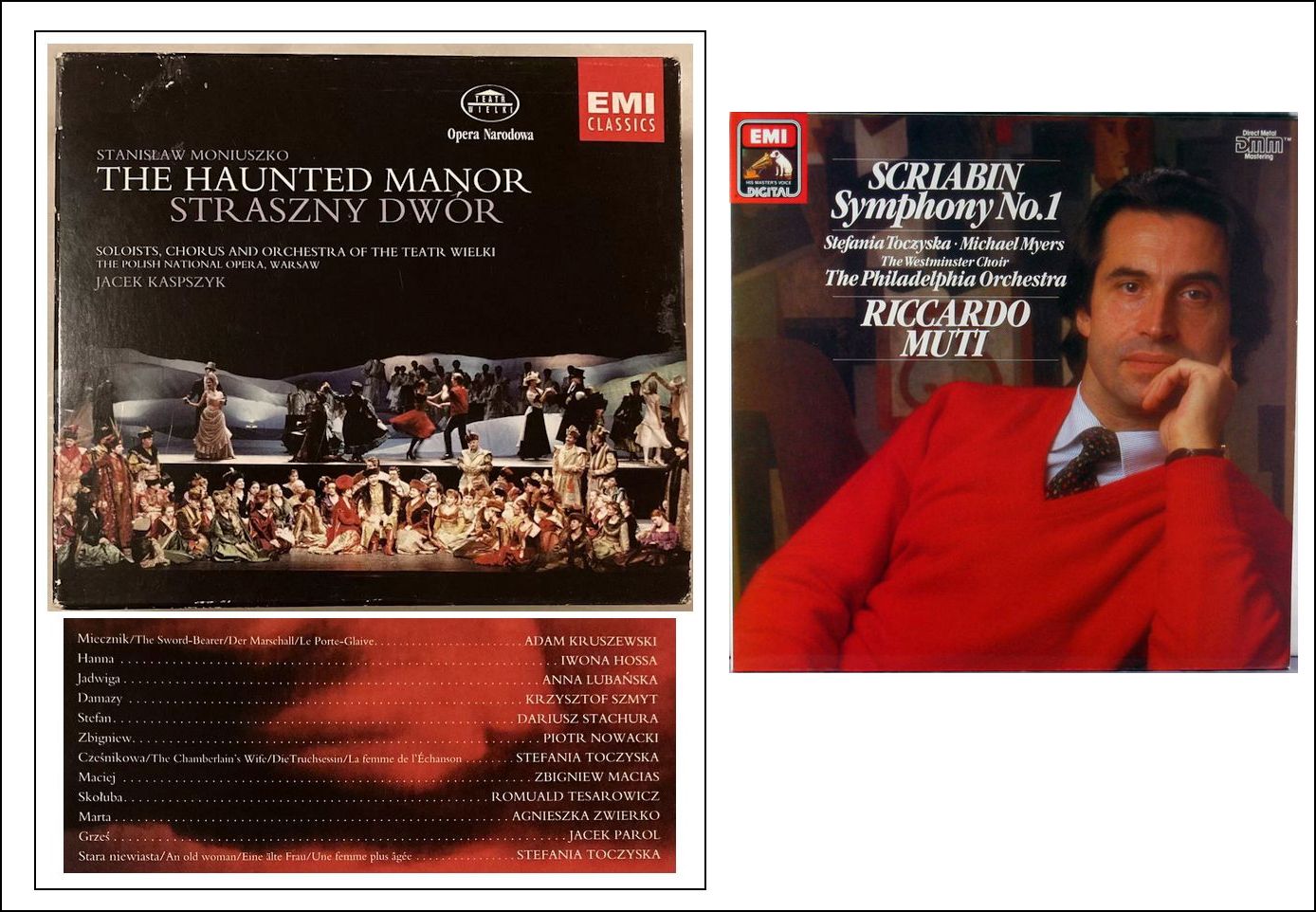

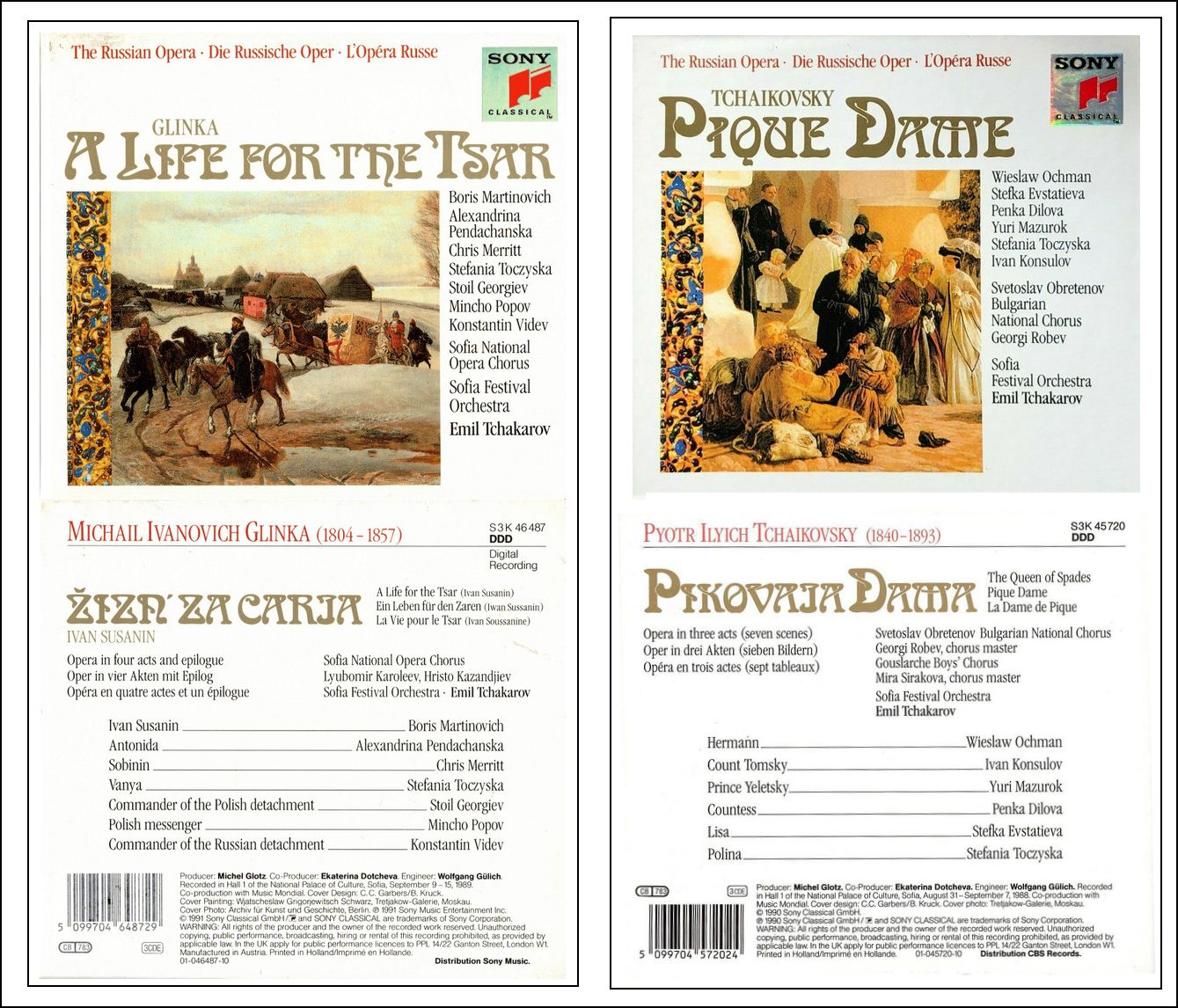

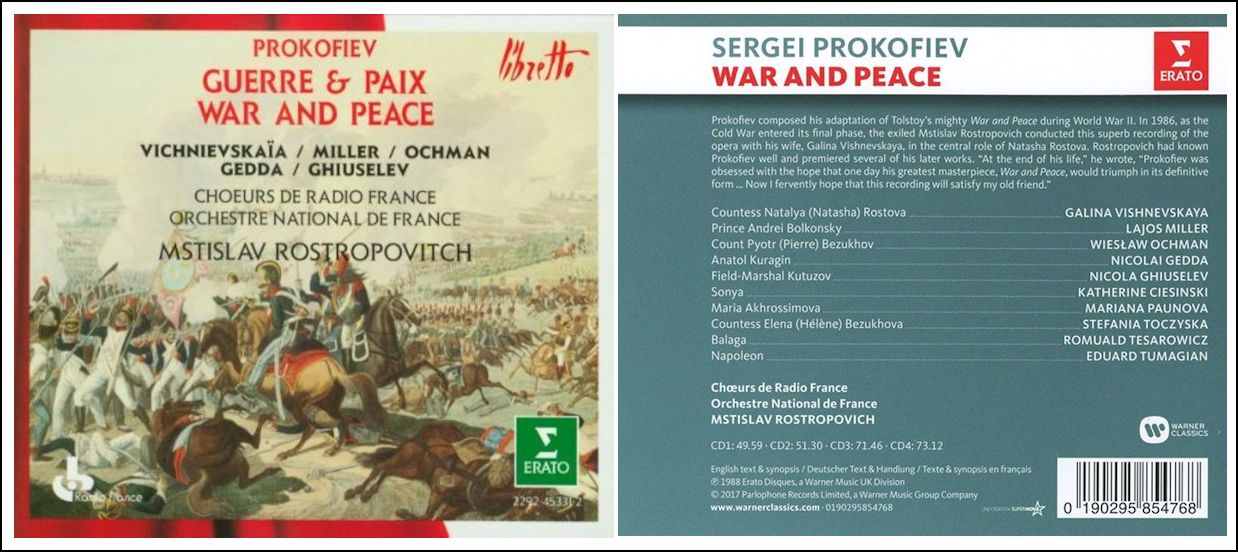

Stefania Toczyska (née Krzywińska), born in Grudziądz, Poland, on 19 February 1943, is a Polish mezzo-soprano. She lived in Toruń, where she attended the Music School ("little conservatory"). There, she married Romuald Toczyski, a music teacher. She moved in 1968 with her family to Gdańsk in order to pursue her higher education. There she studied voice in the Higher Music School (the subsequent Academy of Music) in the class of Barbara Iglikowska, receiving her final diploma (with distinction) in 1973. But even before that, during studies, she was building her career by winning awards in international vocal competitions in Toulouse (1971), Paris (1972) and 's-Hertogenbosch (1973). Her debut occurred in 1973, on the stage of the Baltic State Opera House in Gdańsk, in the title role of Carmen. Initially, her activity was centered locally in Gdańsk, where she kept her position as the leading soloist in the Baltic State Opera, making also frequent guest visits to other opera houses. In 1975, the Baltic State Opera produced, especially for her, Samson et Dalila in 1975 (that same production seen also the next year in Warsaw), and La favorite by Donizetti in 1978 (also seen in Bremen the next year). Her first appearance outside of Poland took place in Basel, when she sang the role of Amneris in Aïda, in 1977. Soon after, with her international career established, she gave a farewell performance in Gdańsk on 15 July 1979, as Dalila. She eventually moved out of Poland and established her permanent residency in Vienna, and her career centered at the Staatsoper. From there, she made frequent guest visits to sing on stages of various opera houses around the world, including her native country, particularly at the Teatr Wielki, Warsaw. On 16 September 1979 she made her American stage debut in the San Francisco Opera, as Laura in La Gioconda (with Renata Scotto, Luciano Pavarotti, Norman Mittelmann, and Feruccio Furlanetto, conducted by Bruno Bartoletti), which was telecast "live" around the world. She made her first appearance at Royal Opera House in 1983 (as Amneris in Aïda), and also sang at the Teatro Colón, in Buenos Aires. In 1988, Toczyska made her Metropolitan Opera debut, as Marfa in Mussourgsky's Khovanshchina. She went on to sing there in Aida, Il trovatore, La Gioconda, Boris Godunov (as Marina Mnichek), Un ballo in maschera (as Ulrica), Rusalka (as Jezibaba) and Adriana Lecouvreur (as the Principessa di Bouillon), with her last performance there, in 1997. Her later roles include King Roger (Warsaw, 2004), Salome

(Herodias, Warsaw 2005), Haunted Manor (Czesnikova, Warsaw 2007), Prokofiev's The Gambler (as Babulenka,

in Berlin, 2008) and

Mamma Lucia in Cavalleria rusticana (Paris 2012, Salzburg 2015). == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

See my interview with Wiesław Ochman

See my interview with Mstislav Rostropovich

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in a dressing room of the Opera House in Chicago on November 13, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1998. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to Alfred Glasser of Lyric Opera of Chicago for translating, and to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.