|

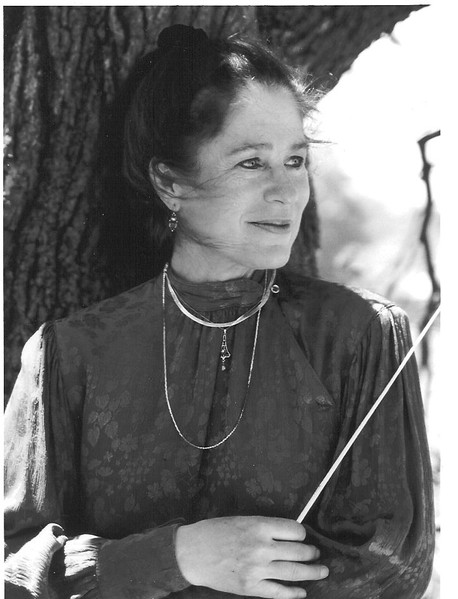

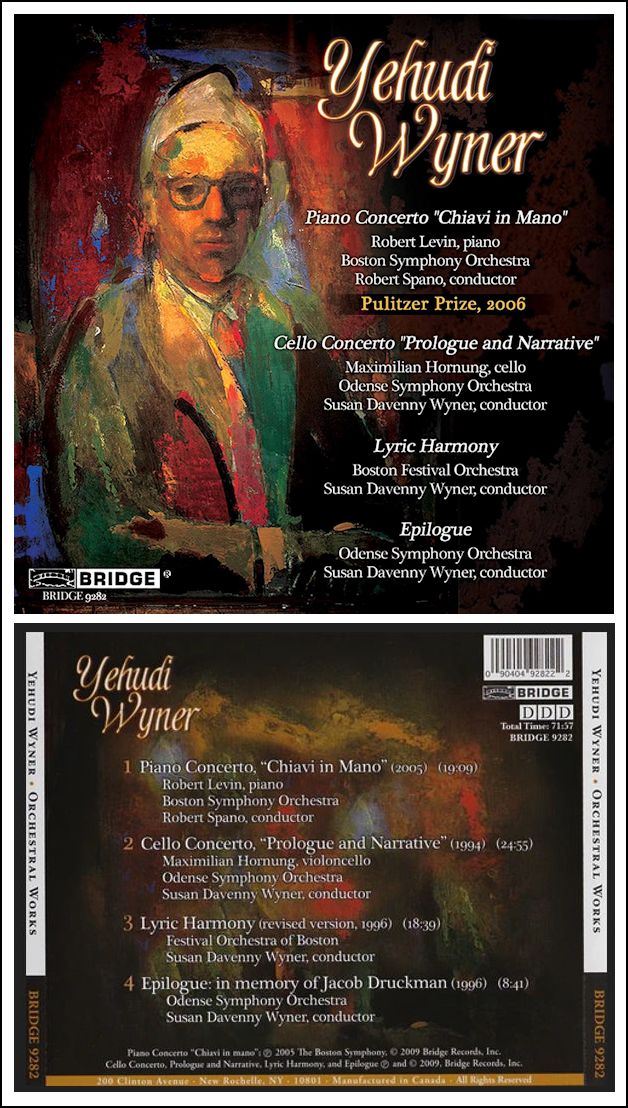

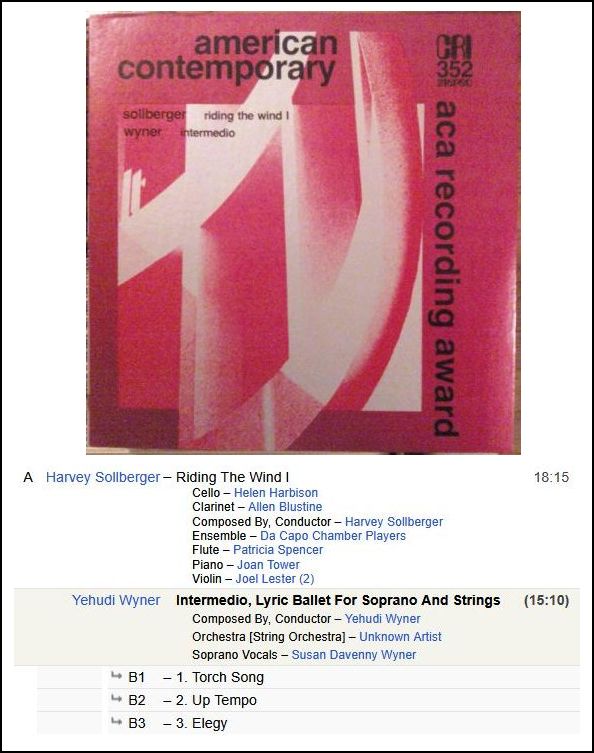

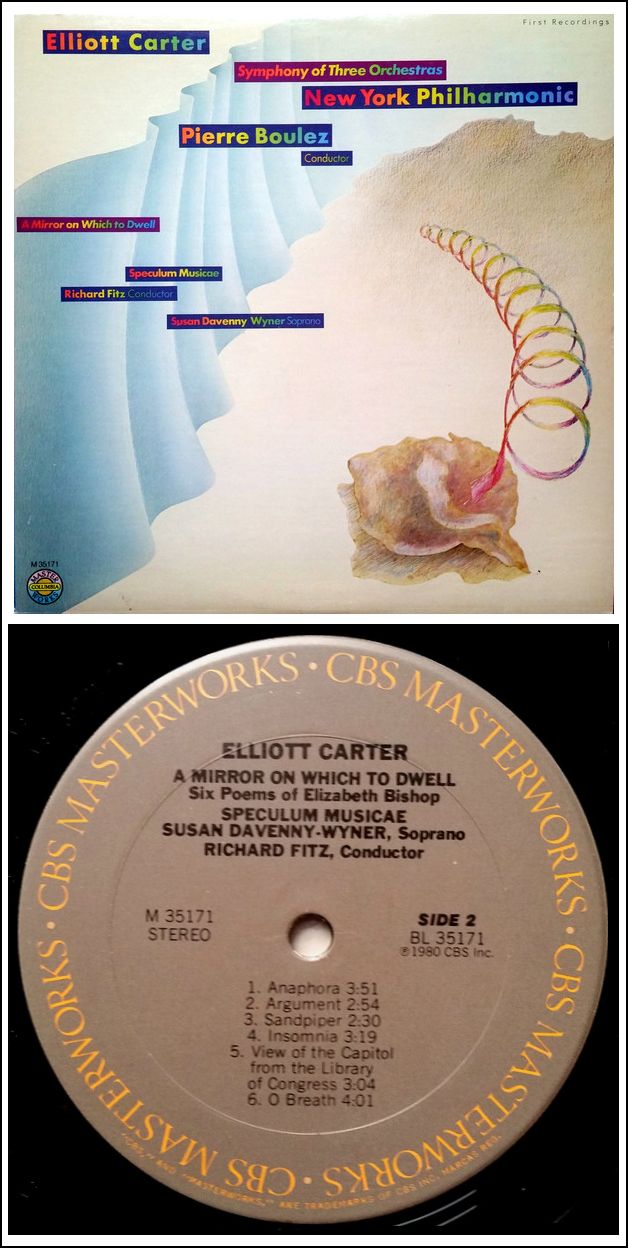

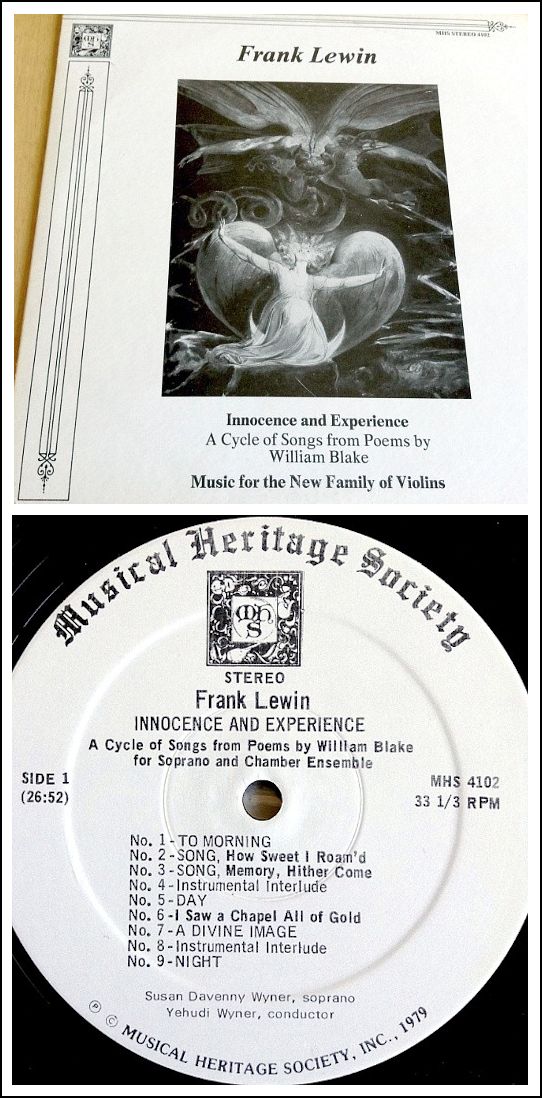

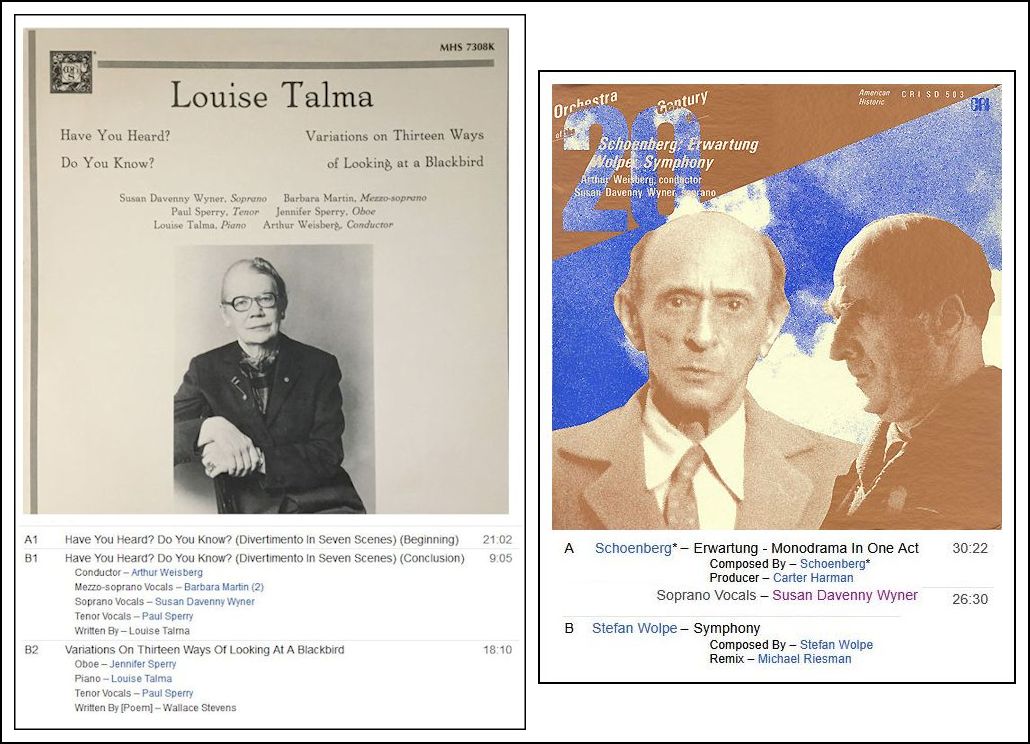

Susan Davenny Wyner (born October 17, 1943* in New Haven, Connecticut) is a nationally-acclaimed American conductor based in Massachusetts. She had a promising career as a soprano, which was ended in April of 1983 by an automobile/bicycling accident that damaged her vocal cords. Her father, pianist Ward Davenny, was professor of music at Yale University. She was originally trained as a violinist and violist. Following early studies at the Cleveland Institute of Music and the Hartford School of Music, she graduated summa cum laude from Cornell University in 1965 with degrees in both comparative English literature and music. In 1967, she married composer and pianist Yehudi Wyner. She entered into vocal studies with Herta Glaz from 1969 to 1975. She received a Fulbright scholarship and a grant from the Ford Foundation, and also won the Walter W. Naumberg Prize. She made her solo debut as a vocalist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1974 under Michael Tilson Thomas. She was later a soloist in Handel's Messiah under Sir Colin Davis with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Symphony Hall and Carnegie Hall. She sang in Beethoven's Ninth Symphony at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., under Leonard Bernstein, who invited her to perform his own Kaddish Symphony and Songfest. Wyner made her first New York City Opera appearance as Claudio Monteverdi's Poppea on October 23, 1977. She received critical acclaim as the lead role in Maurice Ravel's opera L'Enfant et les Sortileges with André Previn. She made her Metropolitan Opera debut as Woglinde in Das Rheingold under Erich Leinsdorf, on October 8, 1981, and also recorded Erwartung in 1981. She had an international career, performing as a soprano soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra London Symphony Orchestra, Metropolitan Opera, New York City Opera, New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, and many others. Besides those already mentioned, she sang engagements with notable conductors such as Lorin Maazel, Seiji Ozawa, and Robert Shaw. She was a successful as a performer of music in both historic and modern vernaculars. She regularly premiered works written especially for her, some of which were recorded for Columbia Masterworks, Angel Records/EMI, Composers Recordings, Inc., and Musical Heritage Society. Following her accident, she studied conducting, leading to a subsequent

career for which she has received critical acclaim. For this, she studied at Yale and Columbia

University and received conducting fellowships for study at the Tanglewood

Music Festival, the Aspen Music Festival, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic

Institute. She has had conducting positions at the New England Conservatory,

the Cleveland Institute of Music, Wellesley College, Cornell University,

and Brandeis University. In 1998, she was the assistant conductor at Chicago's

Grant Park Music Festival, a position that was created especially for her. Since 1999 Davenny Wyner has served as the Music Director and Conductor of the Warren Philharmonic Orchestra in Warren, Ohio. She also leads two opera companies as Music Director and Conductor: Opera Western Reserve in Youngstown, Ohio, since its creation in 2004, and the Boston Midsummer Opera since 2007.

== Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

== Note that some of the recordings used as illustrations on this webpage, which were originally on LP, have been re-issued on CD. |

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 15, 1994. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1998. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.