|

Mary Stolper is a frequent soloist and chamber music performer who has made guest appearances throughout the United States and Europe. Currently, Stolper is Principal Flute of the Grant Park Symphony, Chicago Opera Theater, Music of the Baroque, and the new music ensemble Fulcrum Point. As an active studio musician, she has also played for hundreds of TV and radio commercials. She traveled with the Chicago Symphony for the world-renowned tour of Russia with Maestro Solti, and over 15 European/Asian tours with Maestros Barenboim and Boulez. She acted as the principal substitute for the orchestra for over a decade. Stolper performed with the Chicago Sinfonietta in Vienna, with a performance of Bernstein’s Halil for solo flute and strings. Also, with the Sinfonietta, she performed the United States Midwest premiere of the Concerto for Flute by Joan Tower. While in Prague, soloing with the Czech National Symphony and Maestro Paul Freeman, she recorded a CD called “American Flute Concertos”, on the Chicago based Cedille label. Other recordings include Voices for Flautist and Orchestra by Shulamit Ran, conducted by Cliff Colnot, and her second Cedille release called Chicago Flute Duos. Stolper toured the former East Germany with the Chicago Chamber

Orchestra, and received excellent critical reviews for her performance of

the Nielsen Flute Concerto. This work was recorded with the

Chicago Chamber Orchestra on the Centaur label, conducted by Maestro

Dieter Kober.

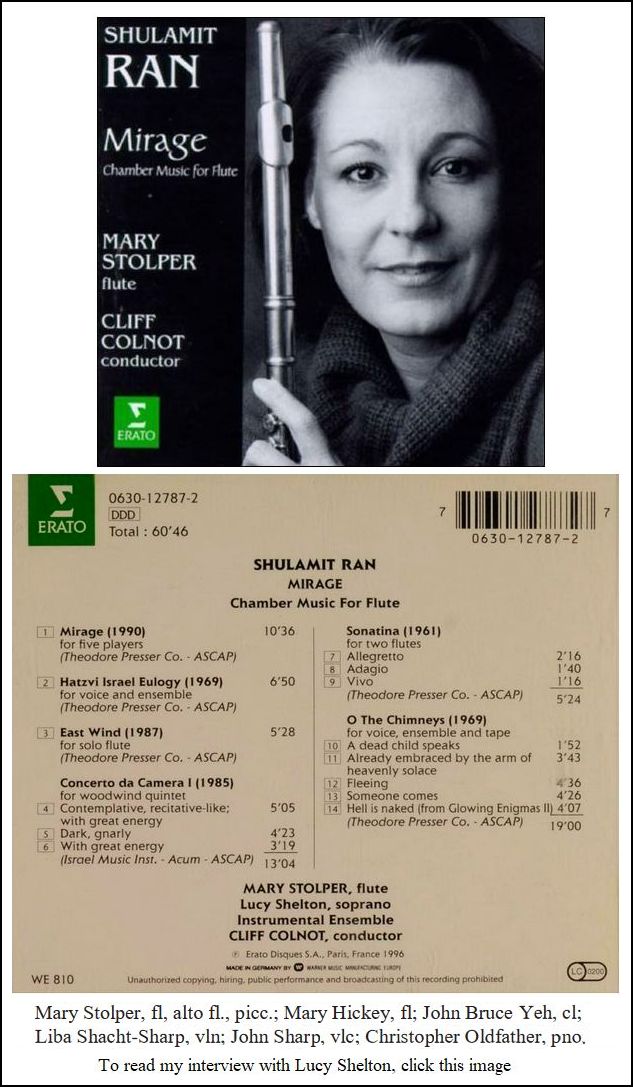

See my interview with John Bruce Yeh Stolper’s performance credits also include Chicago Chamber Musicians, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Ravinia Recital Series, University of Chicago Contemporary Chamber Players, “Live from Studio One” WFMT radio broadcasts, American and Joffrey Ballet Orchestras, Contemporary Chamber Concerts at Orchestra Hall hosted by Shulamit Ran, Da Camera Chamber series in Houston, Texas, and the Old First Church Chamber Series in San Francisco, and the “MusicNOW” series at Symphony Center under Maestros Boulez and Colnot, as well as numerous concerts featuring her extensive skills of contemporary techniques and variety of flutes. Dedicated to the performance of music composed by women, Ms. Stolper invited two Chicago Women Composers/Performers to perform with her at her Carnegie Hall recital debut. Several compositions have been written for her to show her outstanding versatility on the piccolo, flute, alto flute and bass flute. Stolper has been a frequent guest recitalist and lecturer on the subject of Women Composers. She produced and recorded the flute music of Shulamit Ran, former composer-in-residence for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Lyric Opera of Chicago for the Erato/Warner Classics label. Stolper has served on the boards of New Music Chicago, Chicago Society of Composers, American Women Composers, Musicians Club of Women, and the artistic review panel of the Illinois Arts Council. She was one of the founding members, and a past president of the Chicago Flute Club, and has served on the board of the National Flute Association. As part of the flute and harp duo ESPREE, she toured for five years, and was the first-place winner of the first National Flute Association Chamber Music Competition. She was elected to serve the 2006-08 term as President of the Musicians Club of Women. Stolper earned her Masters Degree in flute performance from Northwestern University, where she studied under Walfrid Kujala [piccolo of the Chicago Symphony]. She has also received instruction from Geoffrey Gilbert, Jean Berkenstock, Edwin Putnik, and Donald Peck [principal flute of the Chicago Symphony], as well as performance/master classes with William Bennett, and coaching from Samuel Baron. As a singer/actor/musician, Ms. Stolper appeared in the 1999 Pocket Opera Company production of Don Quixote, in the character role of Sancho Panza. This was repeated again in 2000, along with the production of Golk, where her role was that of the President of the United States. In 2006, she appeared in concert with the Thodos Dance Company of Chicago performing the music of Shulamit Ran. Her articles about various subjects relating to the flute and piccolo have appeared in journals around the world, and have been translated into several languages. She is currently Chair of the Flute faculty at DePaul University in Chicago, and has been on that faculty since 1986. == Biography slightly edited from

the Cedille Records website

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 2002 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in in Chicago on December 20, 2002. Portions were broadcast on WNUR in 2004, 2013, and 2019; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2010. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.