| Abbey Simon (born January 8, 1922)

has been hailed as a super-virtuoso whose appearances in the concert halls

of the world are eagerly anticipated not only by music lovers, but also by

professional musicians who come to hear him spin his own particular magic.

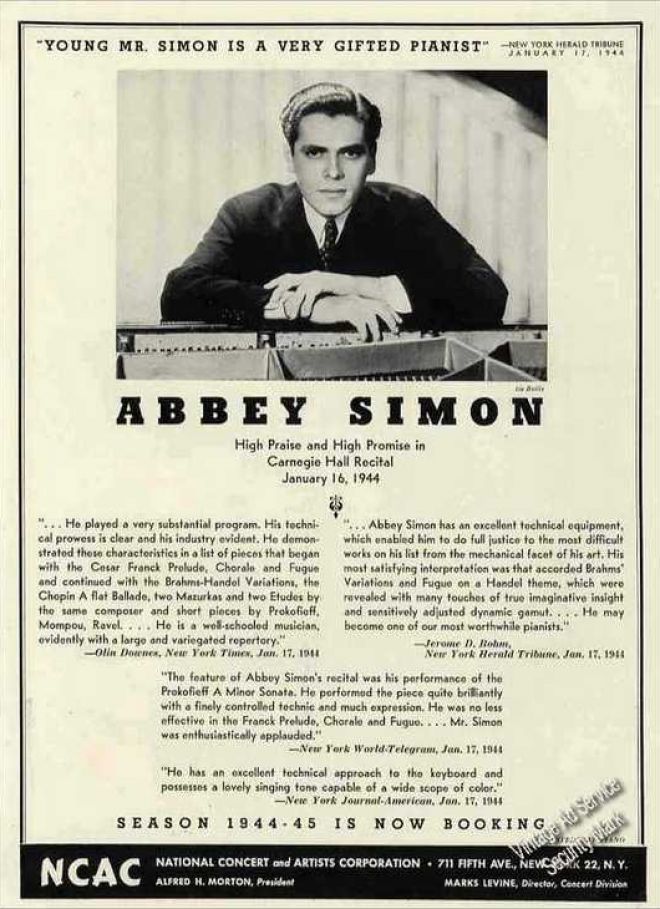

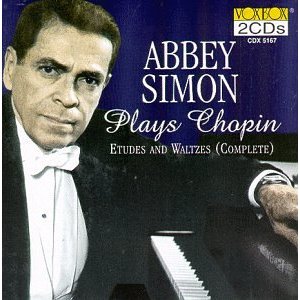

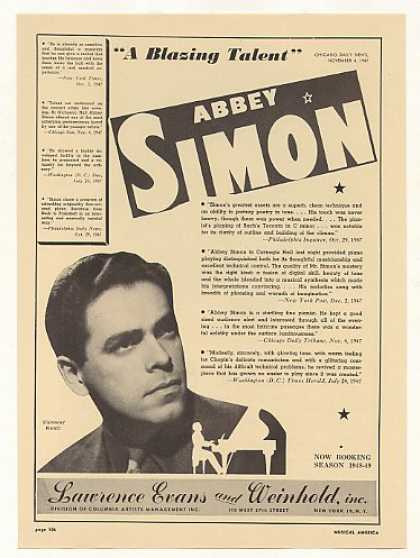

He is recognized as one of the grand masters of the piano. Boston Globe critic Richard Dyer wrote, “Simon’s recital offered more than a glimpse into the fabled golden age of piano playing…His virtuosity is marked not only by speed, power, lightness and accuracy but also by intricate interplay of voices and lambent colors.” And critic Scott MacClelland reported from the West coast “when they’ve written the final chapter on great pianists of the 20th century, the name Abbey Simon will be included. Indeed, that name might well mark the first chapter on 21st-Century pianists as well.” Through the years, critics have hailed Simon’s mastery and noted that his playing has its roots in the great pianists of the past. Improvising at the piano at the age of three, he had natural perfect pitch and began taking lessons at the age of five. After studying with David Saperton, the son-in-law of celebrated pianist Leopold Godowsky, Saperton took him to play for the great pianist Josef Hofmann. At the age of eight, Simon was accepted by Hofmann as a scholarship student at the Curtis Institute where he trained with fellow classmates Jorge Bolet and Sidney Foster, among others. Upon graduation from Curtis, Simon went on to win numerous awards. He made his official debut in New York’s Town Hall as winner of the prestigious Naumburg Award. Following this success he performed at Carnegie Hall a number of times before his debut tour to Europe. His success in Europe was so great that he did not return to the U.S. for some 12 years. He has been the recipient of the Federation of Music Clubs Award, the National Orchestral Association Award, and a Ford Foundation Award. Following his debut in Europe, he received the Harriet Cohen Medal and the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Award. Simon’s recordings for Philips, EMI, HMV, and Vox make him one of the most recorded classical artists of all time. He has recorded all the concertos of Rachmaninoff, the complete works of Ravel, and Schumann’s Carnaval and Fantasy. His Chopin collection encompasses some 20 disks. Abbey Simon has served on the faculties of such noted schools as Indiana University and the Juilliard School. Simon currently holds a Cullen Distinguished Professorship at the University of Houston’s Moores School of Music, where he has been a member of the faculty since 1977. Recently, Abbey Simon was presented in recital on the “Naumburg Looks Back” series in Carnegie’s Weill Recital Hall. |

BD: Do you have any preference for playing with

orchestra or playing solo?

BD: Do you have any preference for playing with

orchestra or playing solo? AS: What sets apart a great piece of music is a

very debatable thing. Think of all of the great pieces of music that

were destroyed on their early hearings or on their first performances.

Carmen comes to my mind just at the

moment, or many of the great piano works which were not played for many, many

years. Think of the passion that we now have and that we now enjoy for

all the Schubert sonatas. When I was a student, nobody played Schubert

sonatas. The first one to play Schubert sonatas that I ever heard

was Schnabel. I never heard Joseph Hoffmann play a Schubert sonata,

or Joseph Levine, or Rachmaninoff, or Vladimir Horowitz, or Rubenstein.

Rubenstein learned one very late in life! What makes a great piece of

music is public acclaim, first of all; it can also ruin a piece of music.

AS: What sets apart a great piece of music is a

very debatable thing. Think of all of the great pieces of music that

were destroyed on their early hearings or on their first performances.

Carmen comes to my mind just at the

moment, or many of the great piano works which were not played for many, many

years. Think of the passion that we now have and that we now enjoy for

all the Schubert sonatas. When I was a student, nobody played Schubert

sonatas. The first one to play Schubert sonatas that I ever heard

was Schnabel. I never heard Joseph Hoffmann play a Schubert sonata,

or Joseph Levine, or Rachmaninoff, or Vladimir Horowitz, or Rubenstein.

Rubenstein learned one very late in life! What makes a great piece of

music is public acclaim, first of all; it can also ruin a piece of music. BD: Are you still learning new works all the time?

BD: Are you still learning new works all the time? BD: I know they have a great opera house down there.

BD: I know they have a great opera house down there. AS: I don’t think that comes into it. You

have to realize you don’t play a musical instrument with your fingers.

A musical instrument is played by the ears. My own theory is that what

sets apart the great artist from the competent one is that he hears differently.

When people say, “The sound of Rubinstein,” Rubenstein played the same old

piano that everybody else played. It was that he had a different conception

of sound. The miracle of Horowitz is not the octaves. Conservatories

are churning out people who can play octaves even faster than Horowitz can

play them. The miracle of Horowitz is the color, the ability to change

color. It’s all of those things, and those are things that are governed

by the hearing. The wonderful sound that Heifitz had is because Heifitz

heard differently. In addition to that brilliant ability, he heard

things differently. All of these great artists hear things.

They have an extra talent, an extra technique, and it’s the hearing technique

because in the most elementary way our ears tell us we played a wrong note.

We have to practice so that we don’t play a wrong note. From then on,

it’s a constant refinement. The ears demand refinement —

play faster, play louder, play softer, do this or that; you didn’t

phrase that nicely. Some people’s ears become more sensitive and more

demanding, and they’re the ones who are the great artists.

AS: I don’t think that comes into it. You

have to realize you don’t play a musical instrument with your fingers.

A musical instrument is played by the ears. My own theory is that what

sets apart the great artist from the competent one is that he hears differently.

When people say, “The sound of Rubinstein,” Rubenstein played the same old

piano that everybody else played. It was that he had a different conception

of sound. The miracle of Horowitz is not the octaves. Conservatories

are churning out people who can play octaves even faster than Horowitz can

play them. The miracle of Horowitz is the color, the ability to change

color. It’s all of those things, and those are things that are governed

by the hearing. The wonderful sound that Heifitz had is because Heifitz

heard differently. In addition to that brilliant ability, he heard

things differently. All of these great artists hear things.

They have an extra talent, an extra technique, and it’s the hearing technique

because in the most elementary way our ears tell us we played a wrong note.

We have to practice so that we don’t play a wrong note. From then on,

it’s a constant refinement. The ears demand refinement —

play faster, play louder, play softer, do this or that; you didn’t

phrase that nicely. Some people’s ears become more sensitive and more

demanding, and they’re the ones who are the great artists.  AS: If I had them, certainly. That reminds

me of a great story. Years ago we had a critic in New York by the name

of Eddie O’Gorman. He went to Curtis and was a clarinetist and a student

of Fritz Reiner. When Reiner came to New York to conduct, O’Gorman

interviewed him and he said, “Mr. Reiner, you’re considered one of the world’s

great opera conductors. Why have you never conducted at the Met?”

He replied, “They never asked me.” [Both laugh]

AS: If I had them, certainly. That reminds

me of a great story. Years ago we had a critic in New York by the name

of Eddie O’Gorman. He went to Curtis and was a clarinetist and a student

of Fritz Reiner. When Reiner came to New York to conduct, O’Gorman

interviewed him and he said, “Mr. Reiner, you’re considered one of the world’s

great opera conductors. Why have you never conducted at the Met?”

He replied, “They never asked me.” [Both laugh] AS: I hope so. I have no idea at the moment,

but I certainly hope so. I love playing in Chicago; I’ve played here

for forty years. I think everybody loves Chicago.

AS: I hope so. I have no idea at the moment,

but I certainly hope so. I love playing in Chicago; I’ve played here

for forty years. I think everybody loves Chicago.|

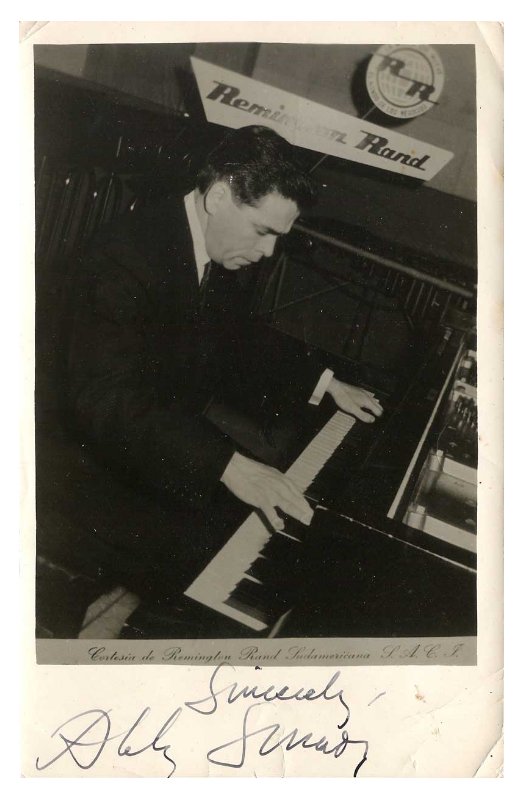

Abbey Simon "In the front rank of the younger generation of pianists" has been a frequent comment by music critics in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and the major cities of Europe, when speaking of the concert appearances or the brilliant American pianist, Abbey Simon. Leading conductors have given high praise to Mr. Simon, who is recognised as an important figure on the musical scene. A New Yorker by birth, Abbey Simon received part of his academic education and his major musical training at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where he was accepted by Joseph Hofmann when he was eleven years old. Shortly after his graduation from Curtis, he won the coveted Walter W. Naumberg award, which carries with it a Town Hall debut in New York City. The debut recital was followed by recitals in new York’s Carnegie Hall and extensive tours throughout the United States and Canada, which were interrupted only for enlistment in the United States army during the war. After an audition, Dimitri Mitropoulos was moved to write of Abbey’s playing : “I confess that rarely has a young artist given me such deep musical satisfaction and brilliant technique at the same time. The boy, for me, has tremendous possibilities to compete with the most outstanding musical personalities of America, because I believe that he possesses not only pianistic abilities, but he also has a musical mind and soul of the first rank.” This glowing endorsement led to appearances with America’s major orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra, The Boston Philharmonic, the San Antonio Symphony Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington D.C., the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, the Buffalo Symphony Orchestra, among others. Mr Simon’s first New York recital in Carnegie Hall was deemed of such unusual merit and received such critical acclaim that he was awarded and appearance with the National orchestral Association, under the leadership of Leon Barzin, for having given the most outstanding piano recital of the year in New York by an artist under the age of 30! In his first tour of the major music centres of Europe, which included Rome, the Hague, Amsterdam, Paris and London, Mr. Simon was enthusiastically acclaimed by near-capacity audiences and by the European press. One critic summed it up thus : “One can try to describe the masterly playing of Abbey Simon, thereby having to exhaust all existing superlatives, but the mysterious beauty of his playing cannot be described by words. We have heard much music in that very hall, but one has to think back twenty years until Horowitz’s debut, to remember an equal event.” Another critic wrote : “A pianist giant… especially, the name of Abbey Simon has to be remembered.” In Scandinavia, Mr. Simon was hailed by the press and the finest American pianist to have played in that part of Europe. In London, Mr. Simon received another accolade when he was awarded the Elisabeth Sprague Coolidge Medal for having given the best performance in London by any artist on any instrument that year. On his first tour of South America, Mr Simon had one of the most phenomenal successes by any artist, playing five recitals in Caracas, four in Lima, five in Buenos Aires, three in Montevideo, plus numerous provincial concerts and orchestral arrangements, resulting in immediate re-engagements for the following season in all places where he had played. He has since toured South America nine times! Abbey Simon has been heard with most of the great orchestras of Europe under such eminent conductors as Sir John Barbirolli, Joseph Krips, Sir Malcolm Sargent, Walter Susskind, Colin Davis, Antal Dorati, Rafael Kubelik, George Szell, Wilhelm von Otterloo, Dean Dixon, Massimo Freccia, Eduard van Beinum, Carlo Maria Giulini, Seiji Ozawa, Zubin Mehta, Erich Leinsdorf. Mr. Simon has recorded under Phillips and HMV labels, and is now under exclusive contract to Vox Records for whom he has recorded the complete works of Ravel, as well as some of the piano repertoire of Schumann and Chopin. Of Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, Stereo Review has written : “Pianist Abbey Simon has achieved in this recording, performances or the piano music of Ravel which I can only describe as being among the best I have ever heard (and I have heard some good ones!). What makes these remarkable even by comparison with the other 'greats' is Simon’s immensely authoritative feeling for the rhythmic structuring, which, when it is fully felt and expressed in Ravel, takes the music over into another dimension of meaning……These are as close to ideal performances as I ever expect to hear, and the recorded sound is well-nigh perfect.” |

This interview was recorded at the Congress Hotel in Chicago, on February 19, 1988. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB three days later, and again in 1990 and 1997. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.