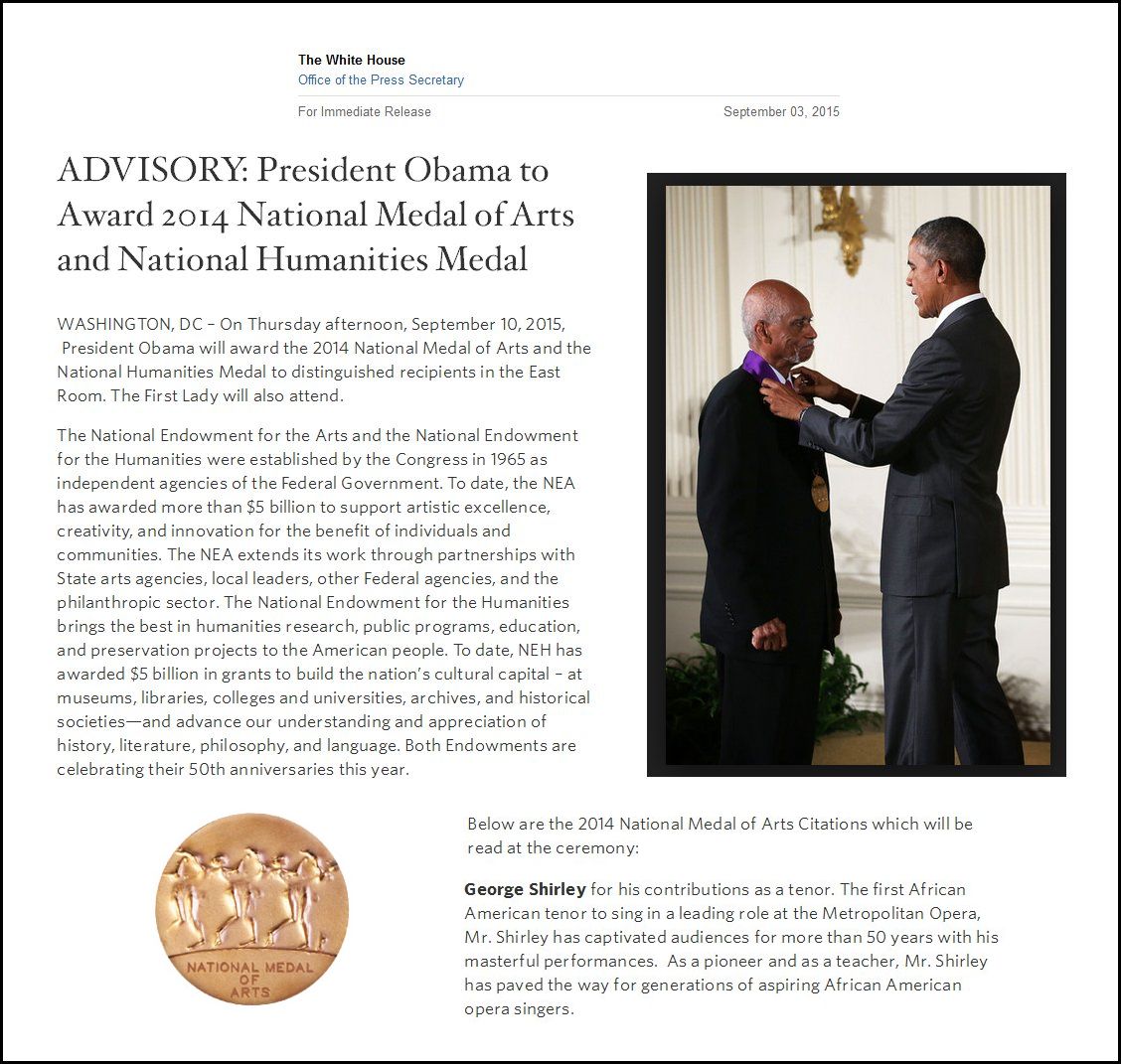

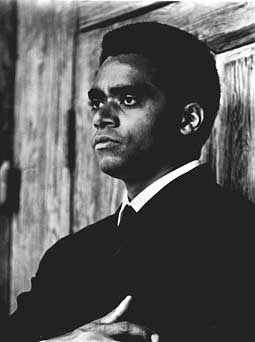

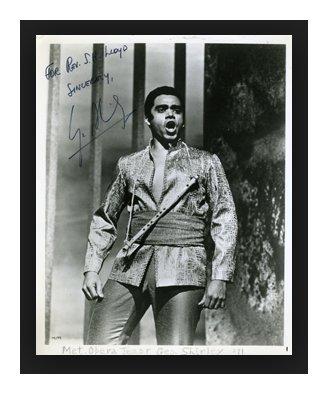

In his career which continues after more than 40 years, George Shirley

has sung leading roles in operas and concerts all over the world.

Besides his musical artistry, he has also had a significant social impact

by being the first African-American to be appointed to a high school teaching

post in music in Detroit, the first African-American member of the United

States Army Chorus in Washington, D.C., and the first African-American tenor

and second African-American male to sing leading roles with the Metropolitan

Opera, where he remained for eleven years as leading artist. And of

special interest to readers of The Opera Journal, Shirley has received

a certificate of appreciation for playing a significant role in establishing

the Legacy Awards for African-American Singers through the National

Opera Association.

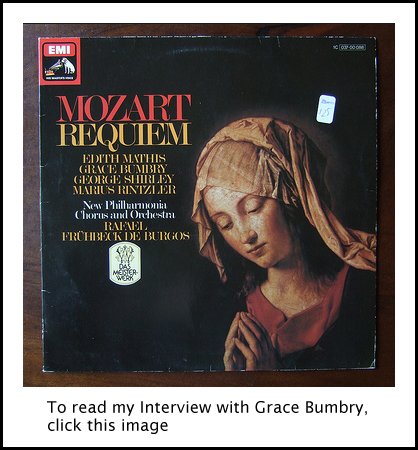

Among the complete opera recordings Shirley has made are title roles in Idomeneo of Mozart, Pelléas et Mélisande of Debussy, and Orlando Paladino of Haydn. He also put on disc another Mozart opera, Così fan Tutte, which won for him a Grammy Award. In addition, there are parts in three operas by Stravinsky, plus narrations in a recent Capriccio CD of Spirit of St. Louis and Ruth with music by Franz Waxman. His interest in contemporary styles is revealed in a recording of Second Voyage for tenor and tape by James Dashow.

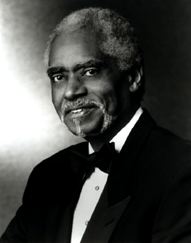

As he states later in this conversation, a love of teaching is

a balance to his performing. He has served as a master teacher in the

National Association of Teachers of Singing Intern Program for Young NATS

Teachers, and was a member of the faculty of the Aspen Music Festival and

School for ten years. In addition, he was selected as one of the Distinguished

Scholar-Teachers for the school year 1985-86 at the University of Maryland,

College Park, where he served as Professor of Voice from 1980 to 1987 and

was invited to join the faculty of the School of Music of the University

of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in September, 1987. At their July, 1992 meeting,

the University of Michigan Board of Regents named George Shirley The Joseph

Edgar Maddy Distinguished University Professor of Music.

George Shirley with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

December, 1970 - Symphony #9 [Beethoven] with Donath, Tourangeau, Talvela; Solti, Hillis

July, 1972 (Ravinia) - Romeo and Juliet [Berlioz] with Dunn, Diaz; Ozawa, Hillis November, 1973 - Missa Solemnis [Beethoven] with Fine, Beatty, Hamari, Adam, Paul; Solti, Hillis December, 1974 (Chicago and Carnegie Hall) - Salome (Narraboth) with Nilsson, Hesse, Ulfung, Bailey; Solti May, 1999 - Three Places in New England [Ives] (Narrator) - conducted by John Adams -- Throughout this page, names

which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

A couple of years ago, George Shirley was back in Chicago briefly to appear as narrator in Ives' Three Places in New England with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. We met between performances at his hotel. Besides our love for great music, I knew that we shared another professional accomplishment, having read that he had produced a series for WQXR radio in New York City called, "Classical Music and the Afro-American."

As I was setting up the recorder, we were lamenting the high costs

of just about everything these days.......

Bruce Duffie: We've been talking about prices and inflation... Are voices these days any bigger or stronger because of vitamins or other factors?

George Shirley: No, I don't think so. From what I've read

about singers in terms of size and quality, Caruso and De Reszke and Lauri-Volpi

might have been even larger back then. I don't know. People

might have been a little closer to the animal state. If we accept

the fact that at some point in history we could run for miles and miles

without getting tired, and if we look at the great cathedrals of the world

which were constructed so that a voice could be heard without microphones...

Maybe we've lost a little bit. Now there's a penchant, especially in

this country, for miking everything. On Broadway, the racket that comes

from the pit is a real hurdle.

George Shirley: No, I don't think so. From what I've read

about singers in terms of size and quality, Caruso and De Reszke and Lauri-Volpi

might have been even larger back then. I don't know. People

might have been a little closer to the animal state. If we accept

the fact that at some point in history we could run for miles and miles

without getting tired, and if we look at the great cathedrals of the world

which were constructed so that a voice could be heard without microphones...

Maybe we've lost a little bit. Now there's a penchant, especially in

this country, for miking everything. On Broadway, the racket that comes

from the pit is a real hurdle.

BD: We don't have miking on the opera stage too much yet, do we?

GS: In some places there is a bit of miking going on surreptitiously, but I don't think it's done in the major houses.

BD: Are voices any better these days? Are they getting more understanding of the music?

GS: Understanding of the music is something that has not undergone any lessening or diminution. For decades now, America has produced some of the best-trained singers in the world. We benefited from the horror of the Second World War, which drove from Europe some of the great teachers and singers and conductors. They came to the United States, and I was part of the generation that was able to work with these people. The training here has really been top-notch and continues to be. American singers are valued in European opera houses for their musicality, and the rapidity with which they learn. So I think the quality of music-making remains high. But as to whether or not singers are better today, I don't necessarily think so. I look at some of the singers I've had the privilege of working with, and I won't list all their names, but I can't say that they're better now.

BD: Then are we at least maintaining the standard?

GS: I think we are. I do believe that we are. I just went to the debut at the Met of a former student of mine, David Daniels, the countertenor. He's an amazing singer, a throwback to earlier times when the wedding of voice and expressiveness was phenomenal.

BD: We seem to be having a real age of the countertenor.

GS: There were three countertenors in that production at the Met, and they were all very good. There are more of them than we probably know... they're coming out of the woodwork! [See my Interview with countertenor Jeffrey Gall.]

BD: You taught Daniels. Do you teach a countertenor differently at all, or is it just another voice that you teach the same rudiments, etc.?

GS: It's another kind of voice that you teach the same kind of rudiments, but I would work with a countertenor the way I'd work with a mezzo-soprano. It's an interesting challenge, but not something that's daunting. One has to find the right repertoire for the singer and realize that the acoustical world that the countertenor occupies is basically the same world as the mezzo-soprano occupies.

BD: There's not more lung-power because he's a man?

GS: No, not particularly. It was interesting

hearing these three countertenors in juxtaposition with two mezzo-sopranos.

Indeed, very different mezzos. The one singing Julius Caesar was a

lyric, and the Queen was sung by a mezzo-contralto. It's a highly individual

thing going from voice to voice.

* * * * *

BD: Let's come back to your career. You sang quite a bit of Mozart and other roles, too. How were you able to balance the lighter repertoire with the heavier parts?

GS: Time between performances is certainly fundamental.

Switching from Don Ottavio to Don José would require enough time to

make that change. The business doesn't always afford one the proper

amount of time for it, though. Singers are performing here and then

running off to do something that begins the next week - either rehearsals

or actual performance - so it's not the best kind of schedule, but that's

the way the business is.

GS: Time between performances is certainly fundamental.

Switching from Don Ottavio to Don José would require enough time to

make that change. The business doesn't always afford one the proper

amount of time for it, though. Singers are performing here and then

running off to do something that begins the next week - either rehearsals

or actual performance - so it's not the best kind of schedule, but that's

the way the business is.

BD: Were you able to conserve your voice so that you had it to give each time?

GS: Enough, yes. I enjoyed the challenge of the varied repertoire.

BD: So when you were asked to sing a role, how did you decide yes or no?

GS: (laughing) I've learned from my own experience and my own mistakes, so I try to convince my students that they really must allow themselves enough time to explore a role before they accept it. Again, the business doesn't encourage you to do that, but it's so important.

BD: The managements want you now, now, now!

GS: That's right. They will say, "We're doing a new production next fall and we'll offer you this many dollars and it's opening night, so will you sign on the bottom line?" That's difficult to turn down, but it can be the difference between a successful debut and one that is fraught with more nervousness than should be necessary or desirable. One should say, "It's not a role I do now, but I'll do it in two years."

BD: So you need to be confident in what you're doing and not think, "Oh my God, what have I done?"

GS: Precisely. And your chances of being confident without having really looked in depth at the role that you're offered are tremendously lessened. Getting a role into your body and your voice takes time. Maybe a year, sometimes a year and a half or two years. Perhaps, depending on the demand, even more.

BD: But isn't some of this ‘getting it into you' just simply doing performances?

GS: That comes later after you've had the time to work out the difficulties in rehearsal. You may look at a role and think it's something that you can do fairly easily. But in every role, there are usually a few pages that offer you challenges that are not immediately apparent when you glance through it. And as you rehearse it, you begin to realize that pages 45-47 are tough, and you need time to work that section in. Then there may be a few other places like that which require repetition, repetition, singing it in.

BD: Now would those pages be the same for a lot of singers, or are those pages hard for you and other pages are tough for other people?

GS: A combination of both. For instance, the end of the aria "Celeste Aïda" is a challenge for most tenors - if you're going to sing it the way it's written.

BD: You need a nice, soft B-flat at the end.

GS: That's right. How often do you hear it sung that way? Rarely! Verdi realized that because he wrote an alternate ending which is rarely done.

BD: Dropping down the octave? [Note: This can be heard in the Toscanini/NBC Symphony recording of the opera on RCA with Richard Tucker as Radamès.]

GS: That's right, and it makes so much sense for what the character's expressing if you don't have a high pianissimo B-flat.

BD: Ah, but the audience wants the big, high note belted out!

GS: But you see, if you do Verdi's alternate version,

you can give them the big high note, but it's not at the very end.

They get their big, high, ringing B-flat, and then it comes down to what

Verdi wanted - something ethereal. But rarely do you hear it done that

way. So that place is a challenge for almost every tenor. The

B-flat at the end of Don José's aria, for instance, is also written

pianissimo, but you rarely hear it that way. Some people will look

at a role and think it's no problem, but then they'll find another spot is

tricky whereas others don't have any trouble at all. So it's highly

individual and you have to give yourself time to claim ownership of a role.

That's hard to do when you're signing contracts right and left without knowing

what you're getting yourself into.

BD: If you think you understand the role and sign a contract for a production a year or two ahead, is it comforting to know that on a certain Thursday you're going to sing that role in that house, or is it cruel to have to be ready on that night no matter what?

GS: If you've signed a contract to do something two years hence, the wise thing to do is to program enough time between the signing of the contract and the opening night so that you have enough time to really work that role into your system.

BD: What about a role you've done many times? You still have to be 'up' on that Thursday.

GS: If it's something that's a part of you and you own it, then it's less daunting. In working with my students, I try to convince them to learn three or four bread-and-butter operatic roles - things that are done all the time, and things that they can put their stamp on. I use as an example Frederica von Stade and Cherubino. She took that role all over the world. How wonderful to walk out onstage of a major house to make your debut in something that you wear like skin. You've already debuted in the role a number of times, so it's no big deal. It's certainly a big deal to make a debut at La Scala, but if it's in a role that you've already sung in Paris and at the Met or San Francisco or Chicago, then three-quarters of your nerves for debut night don't exist.

BD: But you don't want to become blasé about it, do you?

GS: You'll never become that! My experience

was that in great roles, I couldn't be blasé because they're always

demanding. You always are aware of the fact that it is a blessing

to be able to interpret this music. It's never ho-hum. And, if

it's an opening night, your energy is up, but at least it's not competing

with seasoned artists in a role that might not work for you. That puts

you under tremendous pressure.

* * * * *

BD: Are you conscious of the audience every time you go out there?

GS: Yes, because the audience gives you energy. They are

very much a part of it. It's a partnership. If the energy is not

forthcoming from the audience, if there's not that help, then the job is

much harder.

GS: Yes, because the audience gives you energy. They are

very much a part of it. It's a partnership. If the energy is not

forthcoming from the audience, if there's not that help, then the job is

much harder.

BD: You've sung all over the world. Are the audiences different from city to city and country to country?

GS: Oh yes. In Europe, some of the traditions are different. Audiences there are much more interactive with the stage. (Laughter) If they don't like something, they don't mind telling you about it, and if they like something, they will ask you to do it again. I made my debut in Italy in 1960 as Rodolfo in La Bohème, and in the rehearsals, I was told that if I sang the high C beautifully and it goes well, the audience will no doubt ask me to sing it again. So I was told where we'd pick it up for the repeat. And sure enough, at the end they yelled "Bis, bis!" which meant I had to do it again. That doesn't happen in the United States.

BD: It even says in the programs that encores are strictly forbidden.

GS: It doesn't happen, to my knowledge, in Germany. I've sung there, but they were not roles which leant themselves to encores. But the Germans will let you know at the end whether they liked it or not. There are different responses and different atmospheres from country to country and house to house.

BD: When you're up onstage, is there a balance between the artistic achievement and an entertainment value?

GS: I've always hoped that the artistic performance will be entertaining. I don't think of it in different terms. My thrust has always been to be as true to the music and the text and the character as I possibly can, and let the chips fall where they may. I believe if you're true to the book you've been given, and you're honest and thorough in your acquisition of the work, then it will be entertaining and will also be an artistic experience which will hopefully lift the audience above the level of the mundane.

BD: Is that the purpose of opera - to lift the audience?

GS: I think it's the purpose of any artistic endeavor, to transport

them from where they were from when they walked into the theater.

GS: I think it's the purpose of any artistic endeavor, to transport

them from where they were from when they walked into the theater.

BD: Are you transported, or are you the instrument of transportation?

GS: I'm both. If I walk out onstage trying to control things, then I block the ability to be engulfed by the divine inspiration. If I go out and trust my work and open myself so that I'm vulnerable, then I will be transported and the audience will be transported. I will be able to walk offstage and ask someone what happened because I don't know. I was so involved in what I was doing, so how was it?

BD: Sounds like a very delicate balance.

GS: It is, a very delicate balance, but I think it comes down to trusting the moment and trying to create a situation that is much like the very situation we are in right now. We both came into this room, neither of us knowing what was going to happen. We don't know what will happen in the next moment. That leaves us open.

BD: We know where it should go and where it probably will go.

GS: That's right. The difference onstage is that there is a script. We don't have one right now, and my job as a performer is to make the audience feel that there is no script, no score, that this hasn't been done before.

BD: Completely spontaneous?

GS: Right. That is what a performance should do. Even a very familiar opera should seem like it's never happened before. The audience should leave feeling that they've really experienced something that was fresh. As a professional, you need to guard against things becoming routine, but I think the key is coming with no plan to do exactly this at this moment, and exactly that at another moment. For myself, some of the most exciting moments I've had onstage have been when something has happened that was completely unexpected. It just sort of cleared the air and wonderful things then came out.

BD: You go through rehearsals to learn where you'll

stand and when you'll move your arm, etc., so how do you keep those new

directions spontaneous?

GS: Then you get into a groove, and what I try to do when I walk onstage, even though I know that I'll be moving over to that side at that moment, I try to put myself into a mode wherein if something prevented me from getting over to that side, I wouldn't fight and claw to get there. I'd do something else. Otherwise, things become too practiced, too mechanical.

BD: Of course if you have to get to that side in order to grab a knife and stab another character, then there's a problem.

GS: There is a problem, but there are ways of dealing with that problem. If you are open, you'll find those ways. If not, you're liable to stand there, stuck wondering what to do, and before you know it, everything has fallen apart.

BD: You don't want the prompter screaming at you.

BD: You don't want the prompter screaming at you.

GS: That's right, and you don't want the audience to know that something has gone amiss. I remember Boris Goldovsky talking about a performance of Carmen. In the third act, during the fight scene, there was a phony campfire onstage, and when the tenor, David Lloyd, lunged with his knife toward Escamillo, the knife fell into the fire. So what does one do? The music was going on and so he retrieved the knife out of the fire and made it appear that he'd burned his hand rather badly when doing it. But he still held onto the knife and did what he had to do with it. That's what I mean by being open. It was a very real thing to do.

BD: Are you saying that opera is reality???

GS: For those of us who perform it, if it's not, then it ain't gonna work! For us it has got to be as much reality as any theatrical experience is. Any actor or actress knows that this really isn't Paris and this is a fake knife and this is a stage and the audience is out there in front. But if you don't sink into the reality of the play as you did when you were a child, you won't come across as genuine. In working with my students, I use the example of a cat playing with a rubber rat. The cat knows it's not a real rat, and most of the day he walks around it and the toy just sits there. But when the cat decides to play, the pupils in his eyes grow larger and the concentration is on it as though he's preventing its escape. Nothing intrudes as he leaps on it and bats it around. Then when he's finished playing, he just walks away. We have to do the same thing. The soprano may be someone I don't particularly like, but in the first act of La Bohème, I've got to love this person and think that she's the most beautiful woman in the world. She has to be real to me or else all of my singing and all of my actions are empty.

BD: But at the end of Carmen, you've got to be sure the mezzo can get up and take a curtain call!

GS: That's right. (Laughter) This is where the

artistry comes in. The audience has got to believe that I've stabbed

her, and that's the expertise in how I use the knife and how we work together

so that the actual thrust is not seen and her response to being stabbed

conveys the pain. I remember another colleague of mine who was doing

Bohème with a producer who was famous for putting operas together

in very short order - even just a couple of days. He was always busy

making sure that the scenery was in the right place and tended to get flustered

when asked questions by the cast. This colleague of mine was one who

thought things through very carefully, so he went to this producer and noted

that his character was using the wrong kinds of coins because they were not

what was stipulated in the libretto. The producer hurriedly shot back,

"OK, OK, we'll get you the right kinds of coins, and in the last act we'll

kill Mimì for real!!! All right???" (Laughter) So

the convention of theater must take over at certain times, but we performers

must totally commit to what we're doing, totally commit to the moment.

That's the thing that made Callas such a revered artist. She was believable.

I had the great pleasure of seeing her last performance at the Met as Tosca

with Tito Gobbi and Franco

Corelli. Gobbi was a marvelous singing actor with tremendous intensity

and focus. And Corelli knew he had to be on his best behavior, so the

performance was stunning. She insisted on that kind of commitment.

* * * * *

BD: Tell me the secret of singing Mozart.

GS: I approach singing Mozart with the same respect as I do

singing Puccini. It's just different.

GS: I approach singing Mozart with the same respect as I do

singing Puccini. It's just different.

BD: Better different, or just different-different?

GS: I don't know that it's better, just different. The writing is different, the vocal demands are different. Puccini can kill a singer. Mozart never does. Mozart teaches you, and in struggling with him, you may find that the role is not for you, but you will have learned a great deal about singing for having encountered him. If you're not careful, Puccini can send you to the hospital.

BD: Not often in your case, I hope!

GS: No, it didn't at all, but I knew I was in a fight a couple times. For me, Mozart never was a struggle that was at all perilous in any way. It was instructive, it was healthy, and I thoroughly enjoy the challenges that Mozart places before me. Some of my most rewarding moments have been interpreting Mozart roles; in particular, Don Ottavio. I'm especially fond of him because everyone thinks he's a wimp. But he's noble, and he's older. I think it's ridiculous to interpret Don Ottavio as a young man. He certainly is as old as Giovanni, and neither one of them is a spring chicken when we encounter them in the opera. I think of Ottavio not as old as the Commendatore, but not much younger.

BD: They were probably friends.

GS: Very much so. And in Latin countries, you always see younger women on the arms of older men. One of his lines is very instructive. He tells Donna Anna that, "You have both a husband and a father in me." That's not going to come from a guy who is 22 years old. And the music which is given to Ottavio also says he's an older man. When you sing both arias, "Dalla sua pace" is calm and controlled and a heartfelt expression of his love for her. When she is in pain, he is in pain, also. This is a very mature way of looking at it. "Il mio tesoro" is a vengeance aria. It's the one time when we see Ottavio actually lose control. The famous long run is his loss of control. As it winds down and slows down, he slowly regains his composure and addresses those who are standing nearby again. And in the mouth of a younger man, this doesn't fit. Whenever I sang the role, I wore a wig that had a streak of gray in it, and it worked very well. I made my debut at Covent Garden as Ottavio opposite the Don of Tito Gobbi, and the review I cherish said I made Ottavio equally as dangerous as the Don! I appreciated that because I think he is. He never gets his opportunity to go tooth and nail against him.

BD: He's more subtle about his danger?

GS: He follows the rules. He's a knight. It's impossible for him to believe that the Don, a fellow-knight, a man he's known for years, could break his oath and kill and ravish. This is unheard of to him. I enjoy breathing life into Ottavio, and also Tamino. I really love the challenge, not only musically, but also dramatically of Mozart's characters.

BD: Now your voice, being a tenor, dictates that you

sing certain roles. Did you like the characters that your voice imposed

on you?

GS: For the most part, yes. I've sung Pelléas, which is a borderline part that can be sung by a high-baritone or low tenor, and loved him. I love Debussy, period - orchestral works, songs, all of it. I've enjoyed singing Strauss, which is a different kind of challenge. I have done Herod to Apollo in Daphne and the Singer in Rosenkavalier. All of them present different kinds of challenges. I thoroughly enjoyed singing the role of Alva in Lulu. We did the American premiere in Santa Fe back in 1963.

BD: Did the audience ‘get' Lulu in 1963? I know they ‘get' it now, but that was quite a number of years back.

GS: Oh yes. I think the audience was quite sophisticated there. We did it two years in a row, and at that time did not have the completed version, so we had to mime the dénouement over the Lulu Suite for the unfinished third act. It was a wonderful experience. That's a contemporary opera that I can sing any time.

BD: Do you enjoy learning new works and breathing life into new

pieces?

BD: Do you enjoy learning new works and breathing life into new

pieces?

GS: I do, yes. Most recently, I sang an opera by a colleague of mine at the University of Michigan named Michael Udall, who teaches percussion, and was the percussionist with the Santa Fe Opera Company for 20 years. He wrote The Shattered Mirror which is based on themes having to do with Native American lore and mysticism. He called it a 'Percussion Opera.' The accompaniment is all percussion and keyboard. It's fascinating, and uses exotic instruments, including some that he himself designed. It's for three singers - soprano, tenor and baritone - with chorus and dancers. We did it in Ann Arbor, and also in Florida at the International Percussion Convention.

BD: What advice do you have for people who want to write music for the human voice these days?

GS: Do it! (Laughter) Respect the nature of the instrument. The human voice is not a piccolo or a bassoon.

BD: Are you treated like an instrument sometimes?

GS: I think some composers do, and sometimes with very interesting results. But the lyricism of the human voice is still the thing that has the most appeal to the soul of the listener. For those who write opera, I'd encourage them to write chamber operas and works that can be produced in venues that do not require huge outlays of funds. I would love to see people write, as Benjamin Britten wrote, works that can be given in local communities and churches and gymnasiums. In that way, two things can happen - the work stands a better chance of gaining a wider audience, receiving more performances, as well as making friends for the art-form in communities across the country. Big productions are exciting, yes, but it takes a lot of a composer's life to create a major work like that.

BD: Make these works more user-friendly?

GS: Yes, in terms of taking it to the people who might

appreciate it, instead of expecting them to come to the huge centers.

Take it into the communities. To put all that effort into creating

a work and then see maybe two or three performances has got to be uncomfortable

for a composer. When it's such a big piece, only the big houses can

do it, and if it's a powerful work, a chamber version that can be done with

smaller forces would find a lot of activity. In this day and age, smaller

might or might not be better, but it's going to be more accessible, and economically

a better way to go. I'm thinking of Antony and Cleopatra of Barber.

He did the big version which opened the new Metropolitan Opera House, and

then a chamber version which met with more success than the original.

* * * * *

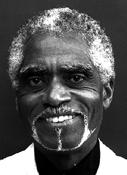

BD: You've just had a 65th birthday. Are you pleased with where you are this point in your career?

GS: Yes, I am, very. I started my professional life

as a teacher of music and choral director in high schools in Detroit, Michigan.

My career was interrupted by military service when I was drafted, and while

I was in the United States Army Chorus, I started studying with a man who

was resident in Washington, D.C., where I was stationed. He'd had a

career as an operatic tenor, and he talked me into considering a change

of professional direction. I decided to give it two years. Things

have gone very well, but I knew that I'd get back to teaching because I love

it. I started teaching on the academic level again in 1980 at the

University of Maryland. I'm able to continue performing at a much-reduced

level, but I have the two things in my professional life that are the most

meaningful to me - teaching and performing. I'm now teaching at the

University of Michigan, where I've always wanted to be. It was the

only University I would have left the East Coast for, because I grew up

in Detroit and I'm as happy as a pig in mud! (Laughter) And the performances

I now sing are very special. Last summer, I sang Sportin' Life in Porgy

and Bess for the first time in Bregenz, Austria.

GS: Yes, I am, very. I started my professional life

as a teacher of music and choral director in high schools in Detroit, Michigan.

My career was interrupted by military service when I was drafted, and while

I was in the United States Army Chorus, I started studying with a man who

was resident in Washington, D.C., where I was stationed. He'd had a

career as an operatic tenor, and he talked me into considering a change

of professional direction. I decided to give it two years. Things

have gone very well, but I knew that I'd get back to teaching because I love

it. I started teaching on the academic level again in 1980 at the

University of Maryland. I'm able to continue performing at a much-reduced

level, but I have the two things in my professional life that are the most

meaningful to me - teaching and performing. I'm now teaching at the

University of Michigan, where I've always wanted to be. It was the

only University I would have left the East Coast for, because I grew up

in Detroit and I'm as happy as a pig in mud! (Laughter) And the performances

I now sing are very special. Last summer, I sang Sportin' Life in Porgy

and Bess for the first time in Bregenz, Austria.

BD: I thought that was a lower role.

GS: It is a role that has been done by baritones,

but it has a B-Flat at the end of his last aria. They just don't sing

it! But I had one of the best times of my life. It was a great

experience. I do some concerts, and I'll be in a Monteverdi opera,

Il Ritorno d'Ulisse in Patria. I was in Glyndebourne back in

about 1974 singing Idomeneo when I first saw the opera with Richard Stilwell, Dame

Janet Baker, and Richard Lewis in the role I'll be doing of the old, blind

goatherd. I figure that at this point in my life, that's about right!

(Laughter) I'm looking forward to it. Jane Glover is conducting,

and John Cox, who staged

that Idomeneo, will be directing. He's a wonderful director,

and it's the first time I've had a chance to work with him since.

BD: One last question... Is singing fun?

GS: Much of the time, yes. When something becomes a professional activity, there are going to be times when it's a little less fun than it might be if you were just doing it for the heck of it - the pressures that are brought to bear, colleagues you might not be very comfortable with or have good relationships with, and your own difficulties. Singing is less fun if you're battling a respiratory illness. When you walk out onstage and you feel you're able to give to the work what you can give, then there's no greater joy. Knowing that you've shared with the audience a great work which on that occasion in that location lived only through you, that can't be beat.

BD: Thank you for the conversation.

GS: Thank you for your interest. Thank

you very much, indeed.

= = = = = = = = = = = = =

- - - - - - - - - -

= = = = = = = = = = = = =

As the interview with George Shirley was being prepared for this presentation, we learned of the passing of Quizmaster Edward Downes. The Opera Journal published my interview with him in 1986, and it can now be found HERE .

For over 25 years, Bruce Duffie was an Announcer/Producer with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago, where his interviews aired regularly. He has also contributed material to this and other publications. Next time in these pages, a conversation with conductor Yakov Kreizberg, and that interview can be found HERE .

Published in The Opera Journal, March, 2002

©2002 Bruce Duffie

© 1999 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on May 7, 1999.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later. This transcription

was made in 2002, and published in The

Opera Journal that March, and also posted on this website at that

time. At the end of 2015, the interview was slightly re-edited, and

links and new photos were added.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.