A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Sharon Graham at Lyric Opera of Chicago

(Names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this website) 1979 - The Love for Three Oranges (Princess Linetta) with Little, Souliotis, Trussel, Gill, Nolen, Halfvarson, Kuhlmann, White, Tajo; Prêtre, Chazalettes, Santicchi, Schuler (lighting for most of these productions) Rigoletto (Giovanna) with Blegen, Pavarotti, Manuguerra/Elvira, Gill, Kuhlmann, Albert; Chailly, Pizzi, Sequi Andrea Chenier (Countess - 5 performances; Madelon - 2 performances) with Marton, Domingo, Bruson, Kuhlmann, Voketaitis, Gordon; Bartoletti, Gobbi, Samaritani 1980 - Lohengrin (Page) with Johns, Marton, Roar, Sotin, Monk; Janowski, Oswald (dir & des) 1981 - Ariadne (Dryad) with Meier/Rysanek, Johns, Welting, Schmidt/Minton, Malta, Negrini, Langton, Harman-Gulick; Janowski, Neugebauer, Messel Romeo and Juliette (Gertrude) with Kraus, Freni, Raftery, Kavrakos, Kunde, Clarey, Cook; Fournet, Melano, Gérard, Tallchief 1982 - Tales of Hoffmann (Voice of Antonia's Mother) with Kraus, Welting, Zschau, Masterson, Mittelmann, Andreolli, Vergara, Kavrakos, Cook; Bartoletti/Schaenen, Puecher, Frigerio Luisa Miller (Laura) with Shade, Ciannella, Brendel, Kavrakos, Washington, Curry; Gómez-Martinez, Merrill, Colonnello, Tallchief 1983 [Spring] - Mikado (Pitti-Sing) with Harman-Gulick/Larson, Rosenshein/Negrini, Curry/Decker, Wildermann, Adams; Smith, Sellars, Lobel [Fall] - Lakmé (Mallika) with Serra, McCauley, Dickson, Kavrakos; Plasson, Fassini, Grossi, Tallchief Cenerentola (Tisbe) with Baltsa, Blake, Nolen, Desderi, Harman-Gulick, Crafts; Ferro, Ponnelle/Asagaroff 1985-86 - Madama Butterfly (Suzuki) with Watanabe, Mauro, Bruscantini, Andreolli, Doss, Del Carlo; Gómez-Martinez, Prince, Dunham Meistersinger (Magdalene) with Stewart, Johnson/Wells/Griffel, Johns, Patrick, Kuebler, Kavrakos; Janowski, Merrill, O'Hearn 1986-87 - Parsifal (Flower Maiden) with Vickers, Troyanos, Nimsgern, Sotin, Becht, Salminen/.Kennedy, Bean; Perick, Pizzi (dir & des), Tallchief Katya Kabanova (Barbara) with Shade, Bailey, Jenkins, Wilderman, Palmer; Bartoletti, Puecher, Schneider-Siemssen 1987-88 - L'Italian in Algeri (Zulma) with Baltsa, Blake, Nolen, Alaimo; Ferro, Ponnelle/Asagaroff Forza del Destino (Preziosilla) with Dunn, Giacomini, Nucci, Kavrakos, Fissore, Andreolli; Conlon, Maestrini 1988-89 - Tannhäuser (Venus) with Cassilly, Secunde, Hagegård, Rootering, Heppner (Walther), Kaasch, Hauman; Leitner, Sellars, Tsypin Salome (Page) with Ewing, Fassbaender, Nimsgern, King, Farinia; Slatkin, Hall, Aster Tancredi (Roggerio) with Horne, Cuberli, Merritt, Cox, Redmon; Bartoletti, Copley, Conklin 1989-90 - Clemenza di Tito (Annio) with Winbergh, Vaness, Troyanos/Mentzer, Doss; Davis, Rochaix, Toffolutti * *

* * *

As can be seen in the program at right, several members of the Lyric Opera School were enlisted for the Chicago Symphony performance of Macbeth, which opened the Ravinia season in June of 1981. Also, see my Interviews with James Levine, Renata Scotto, Sherrill Milnes, and Margaret Hillis. |

BD: Does that opera work well in English?

BD: Does that opera work well in English?

| `Butterfly` Production Pretty But

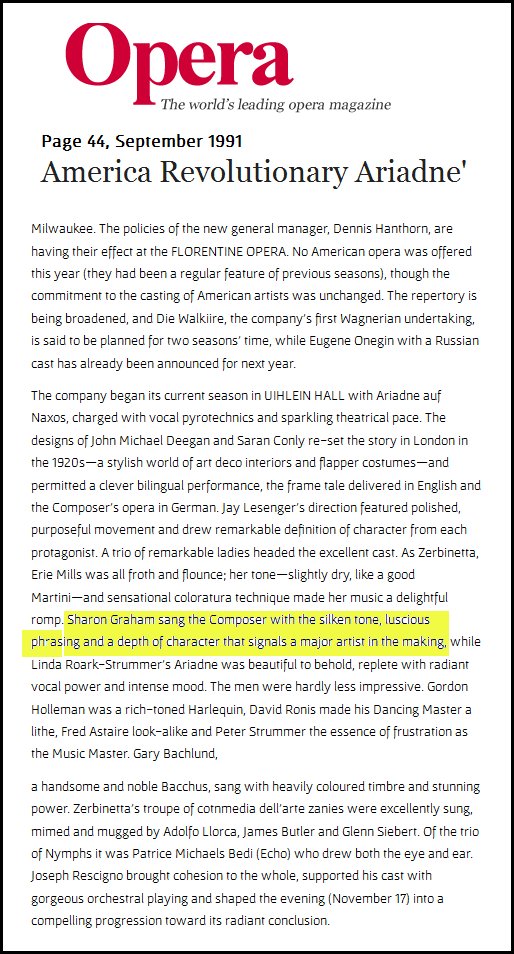

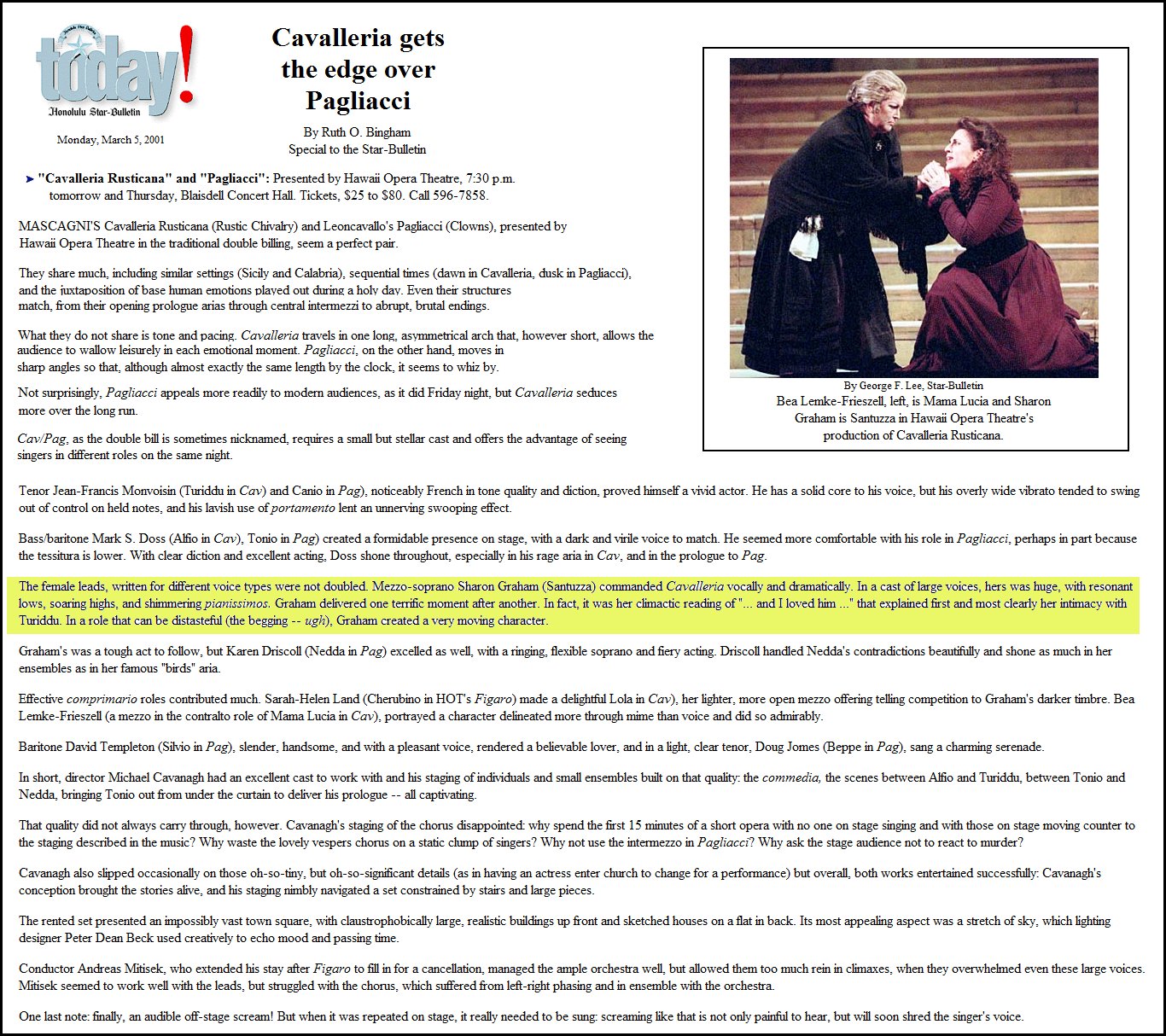

Can Sting January 06, 1986|By Richard Christiansen, Entertainment editor. ``Complete libretto for the opera on sale here,`` announced the vendor, ``and the Bears are winning 21 to nothing.`` On such a note, just before the start of Sunday`s matinee, customers were greeted in the lobby of the Civic Opera House for the first staging in Lyric Opera`s last cycle of ``Madama Butterfly`` performances for this season. Less triumphant and certainly more placid than the Bears` playoff victory, this production of Giacomo Puccini`s opera nonetheless had its own shards of newsworthiness for its customers. Chief among these were the Lyric Opera debuts of Yoko Watanabe, a Japanese-born soprano, in the title role, and Ermanno Mauro, an Italian tenor, as her faithless lover, Lt. Pinkerton. Watanabe, who quite naturally has made a reputation for herself in this role in European opera houses, brings to it a slender figure, an occasional touch of poignance in her acting and a voice that, starting out reedy and shrill in its upper registers, warmed up into a strong instrument in the second act. Unfortunately, for her first performance in this production, she also kept her eyes glued on conductor Miguel Gomez-Martinez in the pit, no matter what events were taking place on stage. This had the effect of giving her portrayal the air of a one-woman dramatic recital, with the other singers and actors vainly trying to relate to her. When the stolid little Christopher Michael Pessetto came out in the second act as her young son, he didn`t look at her either, but just calmly scratched one of his ears while she sang straight ahead and past him in her final aria of grief. As for Mauro, he is a sturdy tenor with a voice that carries forcefully over the footlights and a personality that just lies there. Besides the two principals, this season`s-end re-entry of ``Butterfly`` into the Lyric repertory also had several supporting roles taken by singers other than those who had opened the season last fall with the initial performances. Mezzo-soprano Sharon Graham, vocally and dramatically strong as Butterfly`s devoted servant Suzuki, has a clear, powerful voice that sounds as if it`s on its way to much bigger roles. And the veteran Sesto Bruscantini brought a welcome poise to the theatrics of the proceedings in his role as Sharpless, the U.S. consul at Nagasaki. Back again were the peppy little Florindo Andreolli, in his checked suit, as the sly marriage broker Goro; Catherine Stoltz as Pinkerton`s blond American wife; Paul Kreider as Butterfly`s rejected suitor Prince Yamadori; and John Del Carlo, in his florid Kabuki makeup, as her angry uncle. Director Harold Prince`s generally handsome production in the classic Japanese style, first seen in 1982, still suffers from overkill in the gimmicky use of its turntable scenery, which after a while begins to remind one of a revolving restaurant at the top of a motel. The real standouts of this performance were Gomez-Martinez and the Lyric orchestra, who drew abundant drama and beauty from Puccini`s peerless score. = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = =

`Baby Doe' Is A Great Evening In The Theater By STEVE METCALF; Hartford Courant Music Critic, March 7, 1997 In the minds of most opera goers, the term American opera tends to mean ``Porgy and Bess'' and not much else. Connecticut Opera's charming and poignant production of Douglas Moore's ``The Ballad of Baby Doe,'' which opened at The Bushnell Thursday night, will serve as a powerful corrective. Until Thursday night, the opera had been seen in this city exactly once, in a touring version 37 years ago. In light of its attractive music, colorful setting and, most of all, its stirring and ultimately heart-tugging story -- all the more effective for being true -- it perseveres that the opera still lives only at the edge of the active repertoire. Then again, a few more productions like this one and that may change. For those who haven't been paying attention, ``Baby Doe,'' written in 1956, tells the story of Horace Tabor, a Vermonter who, in the middle of the 1800s, went to Colorado seeking gold, but who found silver. Rich and celebrated, Tabor divorced his wife of nearly three decades and married Elizabeth ``Baby Doe,'' a transplanted Midwesterner and herself a recent divorcee. In the end, the bottom falls out of the silver market and Tabor is ruined. But Baby Doe, the one- time ``miners' sweetheart,'' faithfully stands by her man, broke and broken. Almost everything about this presentation was good. The production itself was a joy: Willie Waters' crisp and sensitive conducting, Ellen Schlaefer's deft understated direction, the handsome sets (borrowed from ``Chautauqua''), the sumptuous costumes, imported from Seattle. But it was the singers who really ignited the show. As the company has acknowledged, this production was explicitly mounted for soprano Mary Dunleavy, as Baby. Dunleavy was worthy of the gesture. From her ``Willow Song,'' (in which, for the record, she soared easily to a high-D) to her scalp- tingling goodbye to her dying husband, Dunleavy was in complete control, vocally and dramatically. It was another triumph in her amazing, and ever lengthening, Connecticut Opera legacy. As the swaggering but oddly sympathetic Tabor, Kimm Julian turned in a richly varied performance, highlighted by his riveting, hallucinatory final scene. Thom King did a fine turn as the silver-tongued presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, to whose star Tabor disastrously attached himself. Anna Maria Syilvestri, a commanding singer who is also a born actress, furnished most of the evening's humor as Baby's plain-spoken mama. But in many ways, it was Sharon Graham, as Tabor's cast-out first wife, Augusta, who proved to be the show's central heart and dramatic fulcrum. In the remarkable scene in which Augusta warns Baby of Horace's impending fall, and later, in a regretful soliloquy near the end of her life, Graham's performance was nothing short of phenomenal. The choral work was strong (it's some of the show's nicest music) and there was solid singing from the Tabor daughters, played by Elizabeth Schmidt and Courtney Ryan. There are those who insist on calling this the Great American Opera. It isn't, and there really isn't such a thing anyway -- not even ``Porgy.'' But ``Baby Doe'' is a great evening in the theater. And great evenings in the theater are not so easy to come by that we should have to wait 37 years between them. THE BALLAD OF BABY DOE -- music by Douglas Moore, libretto by John Latouche; directed by Ellen Douglas Schlaefer; conducted by Willie A. Waters; scenery design by Erhard Rom for Chatauqua Opera; costume design by Kurt Wilhelm for Seattle Opera; lighting design by James Franklin; chorus master, Neely Bruce. Presented March 6 and 8 at The Bushnell in Hartford by Connecticut Opera, George Osborne, general director. |

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 16, 1982. The transcription was made it was published in The Opera Journal in December of 1986. It was slightly re-edited, the photos and liks were added and it was posted on this website in 2016.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.