Soprano Luciana Serra

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Serra as the Daughter of the Regiment

Soprano Luciana Serra appeared with Lyric Opera of Chicago in

two seasons. First, she sang the title role of Lakmé,

by Leo Delibes in 1983. Also in the cast were Barry McCauley, Sharon Graham, and

Dmitri Kavrakos, conducted by Michel Plasson. She

returned in 1986 for the opening night production of The Magic Flute

with Francisco Araiza,

Judith Blegen, Timothy

Nolen, Matti Salminen, Thomas Stewart, Anthony

Laciura, and Kathryn Gamberoni. The Three Ladies were Janice Taylor, Wendy White, and Barbara

Daniels. The conductor was Leonard Slatkin, and

the director was August

Everding. [Names which are links on this page refer to my interviews

elsewhere on my website.]

In between the Flute performances, Serra graciously allowed

me to visit her backstage at the opera house for an interview. She

was happy and enthusiastic throughout our conversation, often relating details

and stories of her performing adventures. Portions were subsequently

aired on WNIB, Classical 97, and now I am pleased to present the entire conversation.

The soprano spoke a bit of English, but we relied on Marina Vecci of

Lyric Opera to translate throughout the meeting.

Since she was our Queen of the Night, I began by asking about Wolfgang

. . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Tell me the secret of

singing Mozart!

Luciana Serra: I think the secret for singing

Mozart is that we have a technique, and above all a lot of style.

BD: How does one learn the Mozart style?

Serra: By work with a specialist in the art

of Mozart. I have lived outside of Italy a long time, and I’ve

had the chance to study with German teachers, particularly people who specialize

in Lieder and in Mozart technique. Also, I found bel

canto, which is my specialty, and is very suitable to the legato

Mozart line of singing.

BD: Is it possible with such coloratura usage,

to bring a lot of characterization to the part?

Serra: Certainly, because the coloratura

should never be an end to itself. I’ve always noticed that each

bit of coloratura writing expresses a different state of mind.

There’s always a reason behind it.

BD: Do you find something new each time you

sing the role? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see

my interviews with Kurt Moll,

Peter Schreier, Margaret Price, Marie McLaughlin, and

Ann Murray.]

Serra: It is always different, yes.

Every time I take up an opera that I’ve already done, I find something

new and different about it.

BD: Do you ever feel that all of the high

notes, especially in The Magic Flute, are like an athletic contest?

Serra: It’s more than pure athletics.

It’s acrobatics! [Much laughter] Even in the Queen of the

Night, the two arias are so different from each other that you can see

this. The first one you can define as needing an agility of grace,

and the second one you can define as needing an agility of strength.

They give you a different characterization, and they express

totally different states of mind. The first one is an expression

of force, or a full explosion of joy, whereas in the second one there

is this anger that appears. So it’s coloratura with character

and expression.

BD: Do you ever find that the audience is

waiting just to see if you will make it up to the top F?

Serra: Certainly, there is this feeling of

great expectation. I feel the audience sits there waiting somewhat!

[Much laughter] It’s not enough, so you need to bring something

else to the aria. I want to add something to it, and then I am very

content. I am very happy about having done this particular Magic

Flute here in Chicago, having gone beyond what my label was before

of being a bel canto singer, and just having this great ability.

I’m going to do the same role at La Scala with Wolfgang Sawallisch.

I have worked with him before, and he told me that he was afraid

that I was too much of a bel canto singer to get the real bite to

it. He felt I was too sweet, and too beautiful, and too delicate,

and not harsh enough, or not menacing enough, or not threatening enough.

I feel that I have reached this in doing the role here in Chicago, and some

of the reviews have noticed that, and have pointed out that I do have the

bite to it.

BD: Do you like playing someone who is evil?

Serra: I like roles that show some temperament!

[Much laughter] I am not bad tempered! I am sweet

and quiet and not harsh, or tough, but I like to be bad tempered on

the stage. [More laughter] When I get the chance of doing

it, I love doing it.

BD: Are most of the roles that your voice

dictates going to be characters who are not quite stable in the head?

Serra: Not, usually. We had the example

of Callas who interpreted many of those roles that I have been doing,

like Amina and Lucia, who sort of go crazy, but this is because they

are victims of a very dramatic situation. They do not themselves

create the tragedy and the drama, but they are victims of it. So

they have to show in their character how they are the focus of all this

drama, because this has all happened to them, and they go crazy because

of the situation. There are very frail women that provoke the drama

and the tragedy around them.

BD: When you’re singing one of these fragile

ladies, do you speak to the women of 1986 who are in the audience, and

who feel that women should not be so fragile?

Serra: It’s true that these ladies and these

roles belong to a different time. Therefore, it’s very hard to

bring them up-to-date, and communicate their feelings to today’s audience.

However, these are not heroines just because they go crazy and

are afraid. It doesn’t mean that they are without character or

without temperament. They have it. It’s just that the tragedy

and what’s happening to them is too hard, and too much for them to bear.

So they break. Suicide and madness are things that are happening

today to men and women. They were not just happening in those days

when women were frailer. In the second act of Lucia di Lammermoor,

in the duet with her brother, I just feel like turning into a tiger. I

want to scratch his eyes out because I’m so mad, but there is no point.

The whole thing is just too much for Lucia. In fact, every time I’ve

done Lucia, the second act duet has always been very much full of drama

because I get really into it. [Playbill from her Lucia at

La Scala is shown at the bottom of this webpage.] But any violence

and rage and anger is not enough. It doesn’t serve any purpose.

I am annihilated by this, and when I get to the wedding, I’m almost doing

everything in a state of sleep or hypnosis, and that is perceived as madness.

BD: After the end of the performance, does

it take you a long time to throw off the character and again become Luciana

Serra?

Serra: It’s a difficult question. I have learned

from many very good directors with whom I have had the good luck to

work with that you can never ever forget yourself, or who you are.

Naturally, there are some roles that really involve you completely,

and sometimes I have found myself on the stage having to really just

think that I’m Luciana Serra. You’re on the stage doing something,

so I have to just go back to Earth and remind myself of who I am really,

and that I’m not the character that I’m doing!

BD: Are there any characters that are perilously

close to your ordinary life?

Serra: [Hesitates] I am quite at a

loss at answering this completely. There are situations in operas

that are similar to what one could experience in life, but on the other

hand, it’s true that they are far away from us today. Perhaps if

I were to sing in a verismo opera where you can find situations

that are a little bit similar to what you could experience today, but

the roles I usually do are a little bit remote.

BD: Do you ever have any longing to sing

verismo works?

Serra: I would love to do that, but I don’t

know if I could. I don’t know if my voice would fit it very well.

This technique of bel canto is typical of what I sing, and I’m

just not quite sure that I should do verismo. My technique

can certainly constitute a base for the future, if I was to go into different

repertory...

BD: [With a wink] Brünnhilde?

Serra: No! [Much laughter] My

God!

BD: [Suggesting roles that might be possible]

What about Mimì or Tosca?

Serra: I like Tosca! Tosca and Carmen

and Turandot are my favorites. It’s just a matter of doing them

because I really like the roles that show great temperament.

BD: Would you be able to project your voice

across an orchestra of eighty or ninety players?

Serra: Why not? It depends on the opera

and on the orchestration. I have had many proposals to do things

of a different nature, and enter a different repertory. There are

lots of singers who change repertory very easily, and so there is no real

reason why I couldn’t change repertory just because I have very easy coloratura.

It’s just that by thinking what I have ahead of me, what is planned and

scheduled... There is that Queen of the Night at La Scala with Sawallisch,

and I’m having my debut at the Met next year in Rigoletto, and

then of Queen the Night in San Francisco. So all the things that are

required are more in my present repertory, and I have no time to think

about doing other things right now. As a student, I started off

with La Traviata, and with Mimì. My professor said

I was a coloratura soprano, and when you’re a coloratura soprano, you

go slowly, slowly. Then later you can sing Manon, Traviata, Mimì.

I have plenty of time, I hope! I have done other things like

Torquato Tasso, which is Donizetti, and is a more dramatic role

[shown at right].

BD: Was this a performance or a recording?

Serra: Both! We did the recording,

and it had a very good success, so we’re now doing it in performance.

After that I have to do Queen of the Night again, so I’m just going to

pursue the coloratura line. It’s not that I haven’t done different

things, or that I cannot do different things. The first time that

I did this role in Torquato Tasso, I played it a lot harder,

a lot harsher and a lot more dramatic, and a lot more imposing. Also,

because I had gained ten pounds, she couldn’t die of consumption at that

time. [Much laughter] So this time I’m going to play it a little

bit frailer, a little bit more consumptive! In view of the fact

that then I have to do more Queen of the Nights and more coloratura parts,

this goes back to what we were saying before, that for the same opera

it would be a new way of viewing it, a new study while adding different

things or changing it slightly.

BD: Are there any roles you sing which you enjoy

because of the vocal technique, but you hate the character?

Serra: No, I don’t hate any character that

I do, because I create them with much love when I’m thinking of a character,

or studying a character. Also, if there was a character I didn’t

really like, I wouldn’t do the role. I wouldn’t be able to do

it with much will and conviction, so there would be no point in doing

it. In all the roles that I have done, I was always trying to

pinpoint the character in a dramatic form, and in such a way that’s

consistent with the music and with the whole character. For instance,

when I was doing Dinorah [Meyerbeer], there the girl suffers from

amnesia, and she is seen dancing in the woods with a goat. So I

made the whole role sort of like dancing throughout. I learned to

dance, and learned all the steps, and I did it throughout the opera so

that the character was totally consistent. When I did The Daughter

of the Regiment, I was a tomboy while I stayed with the regiment,

so I characterized it that way [photo shown at the top of this webpage].

I learned how to play the drums, and do all of these things so that

it was really consistent from the beginning to the end with the music and

the character. It was the same way when I was doing The Golden

Cockerel [Rimsky-Korsakov]. I learned how to do belly dancing,

and I did a lot of that throughout just to focus on the character! [Demonstrates

momentarily, and everyone applauds] It’s a finishing touch for

the character that will really make an impression on the audience in a

convincing way.

* * *

* *

BD: Let’s look at a little of the French repertoire.

How do the French composers compare in their vocal writing to

the Italian bel canto?

Serra: In French music, the way the passaggio

of the voice is written is totally different from the Italian technique.

I like the French repertoire very much.

BD: Is it better or worse for your voice?

Serra: Oh, it’s beautiful, but they are both

different. The French vocal technique is totally different from

the Italian, so that one style of music is written for the French kind

of voice, and the other is for the Italian kind. I had a confirmation

of this difference in techniques when I sang Dinorah, which unfortunately

I only did once. Of that opera we only know the aria [the Shadow

Song (Ombre légère)], but the opera is fantastic because

Meyerbeer lived in all three places

— France, Italy and Germany.

I found in this opera all the true techniques of the three ways of singing

— Lieder

technique, bel canto, and French music. It’s the most difficult

opera I ever sang. The first time I sang it, there were no cuts,

and it lasts four and half hours. It’s very difficult, but I found

it musically very rich, and technically very complete. Of course,

you can sing it all in the same way if you choose, but if you really want

to give the different flavors, then you should really strive to use the

three techniques that are in there.

BD: Should we push for a Meyerbeer revival?

Serra: A festival! [Much laughter] Why

not? You should be happy with that because it’s very, very difficult.

If one wants to do it in the true sense, then it’s very hard, but,

of course, you can sing it in any kind of way.

BD: You don’t need to give names, but are

there directors today who go against the bel canto style, or against

the French style, and are completely wrong-headed?

Serra: No, I’ve always had experiences of great

openness and mutual respect. Many times what I have had from stage

directors is just an indication of what they wanted, and then they left

it to me to develop the character. For instance, I worked with

John Schlesinger, who was doing his first opera. I did Olympia

with him, and he let me do whatever I wanted. He let me build my

own character, but, of course, following his suggestions and hints, and

more or less what he thought I should be doing. It was a good experience,

and he’s a very intelligent man. However, I have worked

with many people who are reputedly very difficult...

BD: Do you sing any contemporary

operas?

Serra: I sang The Last Savage of Menotti, but I don’t

think this is quite the thing for me.

BD: If a composer came to you and said, “I’d

like to write an opera around your voice,” what would you say?

Serra: A tailor-made opera is the best thing

one could have! Franco Mannino wanted to compose an opera for

me, but he hasn’t done it yet.

BD: Returning to the French repertoire, let

me ask you a little bit about the character of Lakmé.

Serra: Lakmé is a character you have

to build anew. There are some operas, like Rigoletto, where

one puts on the same gesture, and in Butterfly one puts on the

kimono and learns the gestures, and you have the character. I had

never seen Lakmé before I did it, so I had no role model

to look up to, or to model myself after. I had no point of reference,

so I had to build it from nothing. Also, we’re talking about a character

that undergoes a radical change. You start with this girl who was

brought up as a princess or a goddess in this garden, knowing nothing

of life. Then, all of a sudden, you have an encounter with a man

and they fall in love. There you have a totally different character

of the woman. I always think of Lakmé the same as what somebody

said in connection with La Traviata. From the vocal point

of view, you need three different kinds of sopranos. You need

the coloratura soprano in the first act, then you need a lyric soprano

in the second, and you need a dramatic soprano at the end. The same

is true of Lakmé, because you have the best song, which is this

huge coloratura thing after you’ve sung already a lot of the role in a different

way. Then you continue singing something which is again totally

different. So it’s just the coloratura thrown into a dramatic role.

BD: Do you sing any Massenet?

Serra: Yes, I am scheduled to sing Manon

next year in Italy, but I haven’t quite decided yet, because for next

year, in addition to Manon, I would have to learn four new operas, which

is a lot. So I don’t know if I can fit it in. I feel that

I should devote a whole month to prepare something like Manon, and I don’t

have that kind of time next year to fit it in completely. It will

be another début, but it’s not like I’ve never done that kind of

repertory. But anyway, I will have to think about it very carefully

before I do it.

BD: Are you singing too much?

Serra: I don’t think so! I never sing two

operas at the same period of time. I always try to get some rest,

however short, between the end of one project and the beginning of rehearsal

for the next one. Naturally, it’s very hard to say no to many things,

but I feel it’s necessary.

BD: Is it comforting to be booked two or

three years ahead?

Serra: I find it very reassuring, yes. But

I also want to live, and not only to sing and work! [Laughs] I

don’t know how to explain it, but I feel that when I’m on holiday I

can stay immersed in a bath of ice for an hour and never get sick! However,

when I start singing, I have to be careful with air-conditioning, and

with the air drafts. This thing of being prone to health problems

is not only something that’s on my mind, but I really get ill if I’m careless.

Perhaps I’m too studious about my profession, but there is no other

way. That is the way I am, and I can’t do otherwise. I feel

a great sense of responsibility towards the audience, and the commitment

that I have taken. So I have to go through with it.

* * *

* *

BD: Do you sing any roles in translation?

Serra: My preference is the original, of

course, and I’ve almost always done whatever the role is in the original

language. But I have done The Golden Cockerel in a new

translation by Fedele D’Amico, who is a very important Italian musicologist.

It was a very good experiment, and an excellent translation, made

with a lot of good judgment.

BD: Do you work harder at your diction when

you know the audience is going to understand every word?

Serra: I take particular care in my diction every

time, no matter what language the opera is in, because I feel that diction

is part of voice production and technique. I had a very good satisfaction

recently when I did Lakmé in French in Bologna. I

had done Lakmé here in French, but before then they had

done it in Italian in Italy. That was another opportunity for me to

do a role in translation, but I insisted that they do it in French in this

particular version. The public of Bologna is a very warm audience,

but not always too ready to accept things that are not in Italian. But

this time I had unanimous consensus from the public, saying that even

though they didn’t know the opera very well, and they didn’t know French

necessarily, they felt they understood everything I sang, and that my diction

was excellent, and they could hear every word.

BD: Do you like this new gimmick of having

supertitles in the theater?

Serra: Yes. I like it because I can see

that the audience really takes part a lot more in the opera when there

are supertitles than when they aren’t used. I realize that it’s

a very good thing.

BD: What do you expect of the pubic that comes to see

you?

Serra: I ask a lot more from myself than from

the public. If you ask a lot from yourself, then the audience usually

follows.

BD: Do you think opera works on television?

Serra: The television has had a great role in bringing

opera to a lot of people. Lots of people actually started liking

opera because of television. However, unless an opera is made

for television or is to be done in a TV studio, it’s very hard to catch

the whole picture. For instance, in the video that they did of

The Tales of Hoffmann in London, I could see how it does kind

of betray what was happening on the stage. It had a very, very complex

staging, and when I saw that video, they could only capture a part

of what was happening. So it was not as good as the real thing.

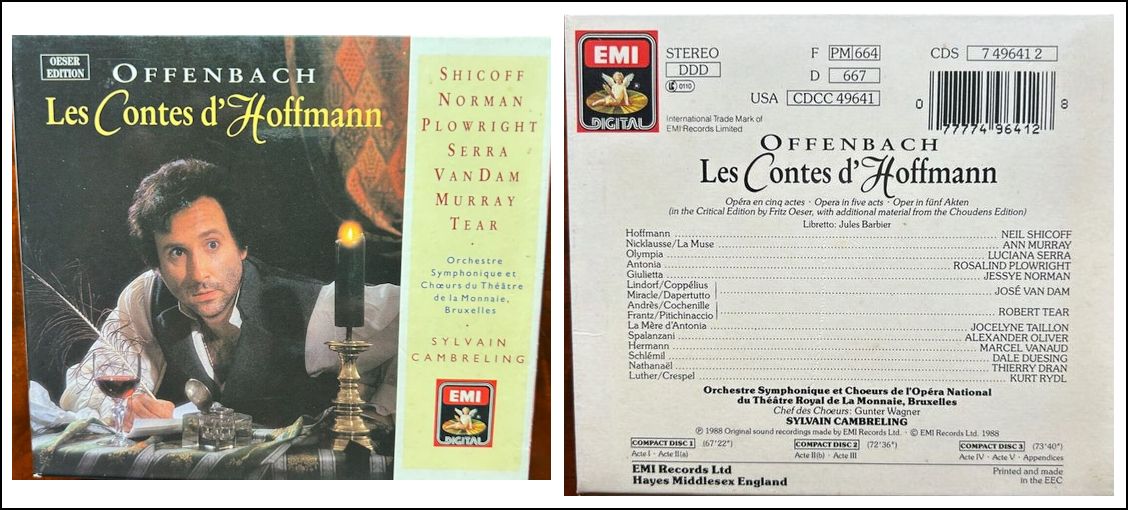

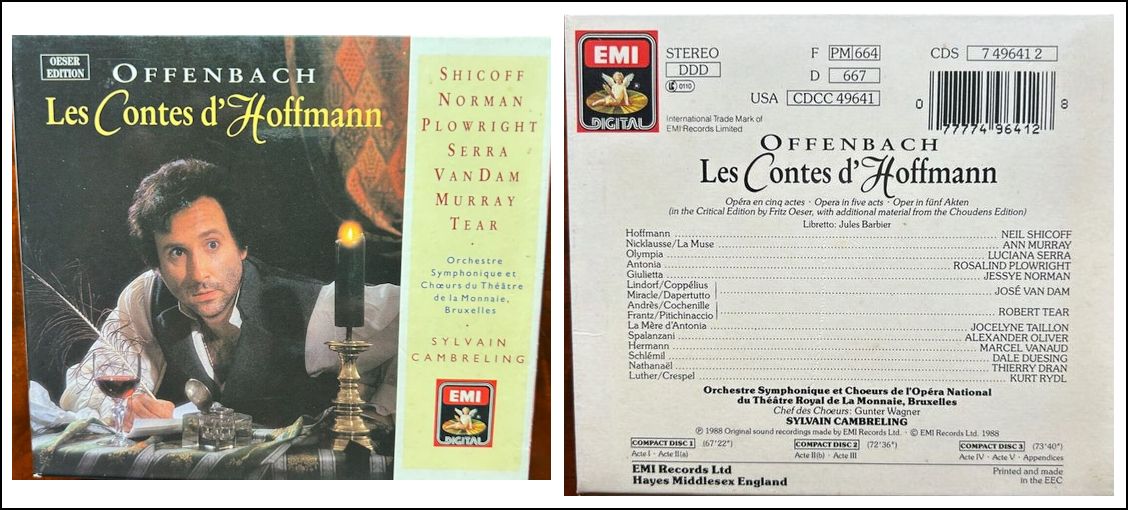

BD: Let me ask about some of your studio

recordings.

Serra: I did The Magic Flute with

Sir Colin Davis [shown above-left], and I also did The Tales

of Hoffmann with Sylvain Cambreling

[shown immediately above. Also, see my interviews with Neil Shicoff, José van Dam, and

Dale Duesing.]

BD: Did you sing one role or three?

Serra: Just one, Olympia. That’s my specialty!

Then I have some live recordings like Fra Diavolo by Daniel Auber,

and L’Ajo nell’Imbarazzo of Donizetti, which were recorded live

from theaters. There is a series by Fonit Cetra which collects rare

or lesser known operas, and great productions, and L’Ajo

is one of the best things the Italian Radio did.

Fonit Cetra was founded in 1957 from merging

two already existing labels: Cetra (acronym from Compagnia per edizioni,

teatro, registrazioni ed affini), owned by RAI and previously EIAR, and

Fonit

(acronym from Fonodisco Italiano Trevisan), founded in 1911

in Milan. Both labels had already been popular. Fonit Cetra continued

to use the two old names on their records, and maintained two different

offices in Turin and Milan, until the 1970s, when the main headquarters

were relocated to Milan. In July 1987, the company's name was changed

to Nuova Fonit Cetra. In 1997, it became part of RAI Trade. Then in 1998,

it was sold to Warner Music Group which acquired its catalogue.

|

I also did Aureliano in Parmira [shown at left], which

was one of the first operas written by Rossini, and was last given in

the theater in 1836. It was written for Giovanni Velluti, who

was a famous [alto] castrato of the time. A big surprise when they

did it five years ago was that it uses the same overture that appears in

Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra,

and The Barber of Seville! The only difference is two more

dramatic trombones in this one. The opening chorus is the same

[sings a few measures], and the Cavatina [Una

voce poco fa] is the same

as Rosina! [Starts singing again!] [With a wink]

Rossini was very lazy, and was pulling things from one opera and

putting them in another!

I also did Aureliano in Parmira [shown at left], which

was one of the first operas written by Rossini, and was last given in

the theater in 1836. It was written for Giovanni Velluti, who

was a famous [alto] castrato of the time. A big surprise when they

did it five years ago was that it uses the same overture that appears in

Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra,

and The Barber of Seville! The only difference is two more

dramatic trombones in this one. The opening chorus is the same

[sings a few measures], and the Cavatina [Una

voce poco fa] is the same

as Rosina! [Starts singing again!] [With a wink]

Rossini was very lazy, and was pulling things from one opera and

putting them in another!

BD: It’s not a pastiche, is it?

Serra: No, this is a very interesting work,

and the role of Arsace [in Aureliano] is a beautiful part. Then

there are works like Torquato Tasso which I did. I also

have many recitals, records, and then I have a concert that I’m preparing

for right now which will be coming out in recording. Then I have

a record of great arias of the French and Italian repertories with the

orchestra, where these new crazy cadenzas have been created for me [shown

above].

BD: Can the commercial recordings be too

perfect?

Serra: I’m not very fond of digital recording.

I find it to be too perfect, a little bit too antiseptic, and not live

enough. I heard this last record of mine

— the arias with orchestra

— and it is an

analogue recording which I like very much. You can feel the presence

there, and the atmosphere is good. But the digital recordings are

just a little bit dead, a little bit too perfect. [Pauses a moment]

Philips and EMI will be mad at me for saying this, so perhaps I shouldn’t...

The sound technician, who is a very famous guy, and a great guy himself,

agrees that the analogue is better than the digital. But he says

it’s his job, and he makes a living out of doing this. I like live

recordings a lot. I feel that perfection is a very good thing to

have and to achieve, but when you have a recording of something that happened

live, you have the feeling of being there. You close your eyes, and

you hear all the noises in the theater, and the applause, and it gives you

the impression of being part of it.

BD: With all of your experiences, is singing

fun?

Serra: Yes! I love in particular comic opera,

as I’m good at that! If it were not such a hard work to do comic

opera, I would have even more fun with that. I had particularly

a very good time in Turin when we did the L’Ajo nell’Imbarazzo.

There is a final Rondo in three parts which is about women, and how they’re

treated as servants, but they’re born to rule and to command.

This modern theater is very open at the sides. They put the maestro

— who was playing

the recitatives on the fortepiano, and who was dressed like Donizetti

— outside of the

pit and into the audience. For the first part of the Rondo, I went

out into the audience! I stepped down off stage, and I addressed

the women in the audience. I sang about the women being treated as

servants, but being born to rule. Then I stepped back into character,

and addressed the maestro who gives the tempos, and then came back to the

stage. That’s the finale, and it was an enormous success. As

you know, Papageno steps out in The Magic Flute. The men

usually do that stepping into the audience, but women never have done

that before to my knowledge. One evening, it was not a public performance,

but was by invitation. There were about 95 mayors of European cities.

I stepped into the audience, and they picked up my dress and started

touching me. I was embarrassed over this because I didn’t quite

know how to react. But they were really caressing her dress because

they’d never seen a prima donna so close within the performance.

[Much laughter]

BD: Are you coming back to Chicago?

Serra: I hope so! I like Chicago very

much because I have my friends here, and Marina [who was translating]

is the first! Normally when I go to a place to stay for a month or

a month and a half, as it is here, I find it extremely long. But

going to Chicago, it feels like I’ve just arrived here and it’s almost

time to start packing again! The time just flew by. I’ve had a

nice time. It’s a very nice company, with a

very nice theater. It’s all a very nice place with many friends, and

all of that helps.

BD: I’m glad we make you feel welcome.

Serra: Absolutely!

BD: Thank you for being a singer.

Serra: Oh, thank you! Thank you very

much! It’s the best compliment I have ever received.

See my interview with Peter Maag

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 4, 1986.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989 and 1996.

This transcription was made in

2024, and posted on this website at

that time. My

thanks to British soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here.

To read my thoughts

on editing these interviews for print, as

well as a few other interesting observations,

click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce

Duffie was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until its

final moment as a classical station

in February of 2001. His interviews

have also appeared in various magazines

and journals since 1980, and he now continues

his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more

information about his

work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a

full list

of his guests. He would also like

to call your attention to the photos

and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive

field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and

suggestions.

I also did Aureliano in Parmira [shown at left], which

was one of the first operas written by Rossini, and was last given in

the theater in 1836. It was written for Giovanni Velluti, who

was a famous [alto] castrato of the time. A big surprise when they

did it five years ago was that it uses the same overture that appears in

Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra,

and The Barber of Seville! The only difference is two more

dramatic trombones in this one. The opening chorus is the same

[sings a few measures], and the Cavatina [Una

voce poco fa] is the same

as Rosina! [Starts singing again!] [With a wink]

Rossini was very lazy, and was pulling things from one opera and

putting them in another!

I also did Aureliano in Parmira [shown at left], which

was one of the first operas written by Rossini, and was last given in

the theater in 1836. It was written for Giovanni Velluti, who

was a famous [alto] castrato of the time. A big surprise when they

did it five years ago was that it uses the same overture that appears in

Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra,

and The Barber of Seville! The only difference is two more

dramatic trombones in this one. The opening chorus is the same

[sings a few measures], and the Cavatina [Una

voce poco fa] is the same

as Rosina! [Starts singing again!] [With a wink]

Rossini was very lazy, and was pulling things from one opera and

putting them in another!