|

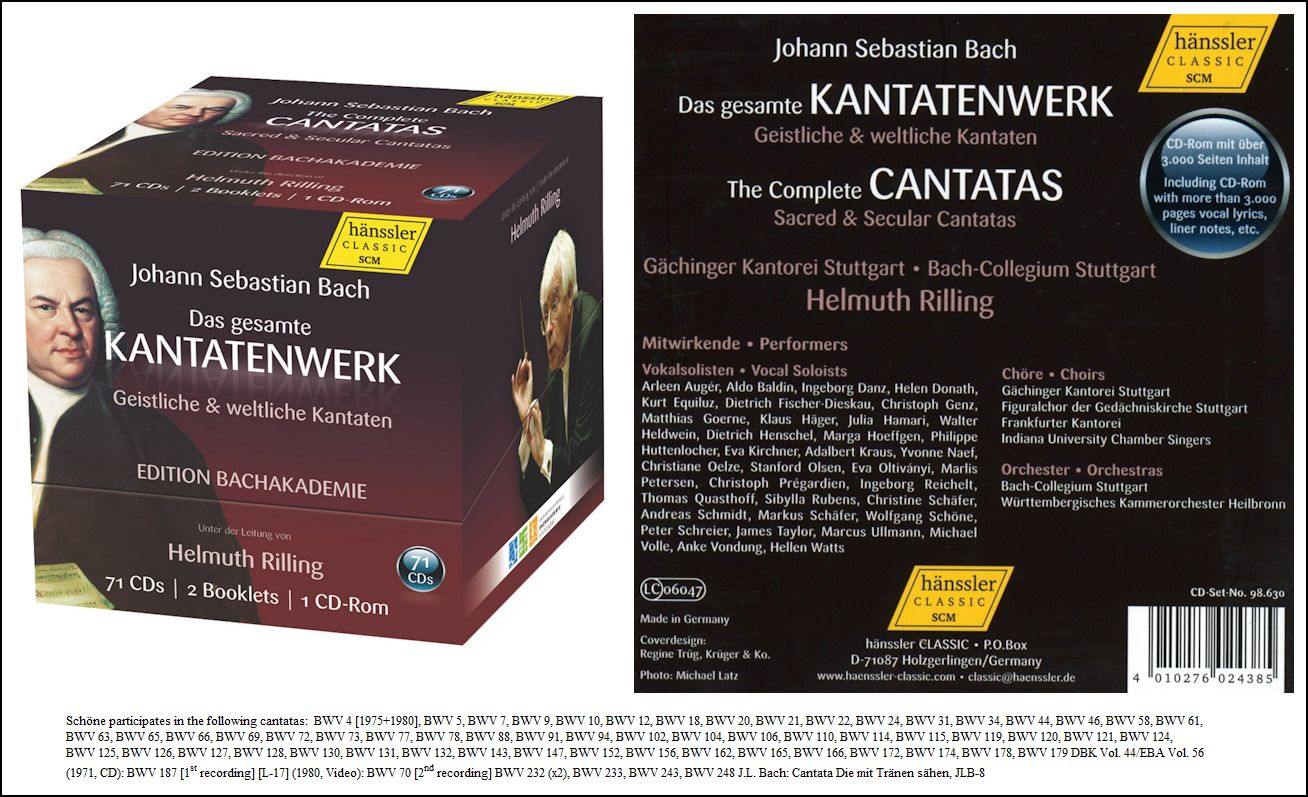

*Note that the Bach Cantatas website, from which the

brief biography above is taken, uses the designation bass-baritone, but,

as he says in the interview, he is a baritone! He also speaks about

being listed as a bass on some recordings. A more detailed biography from another source follows

in this box.

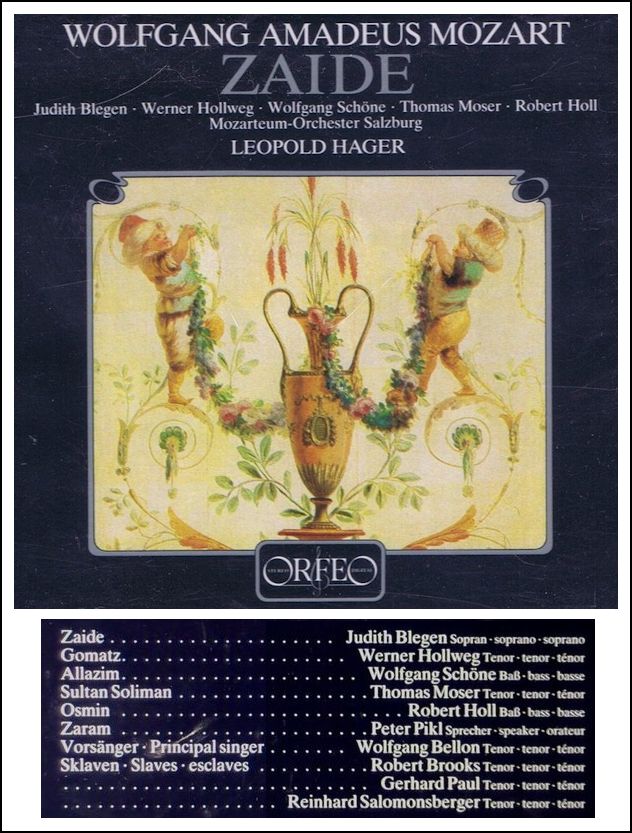

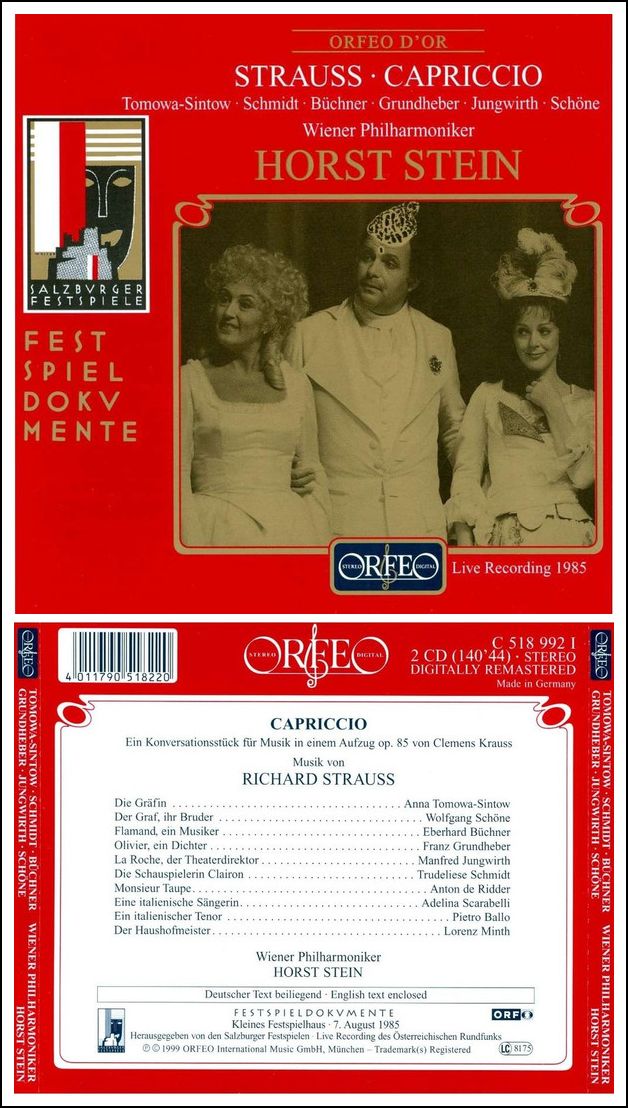

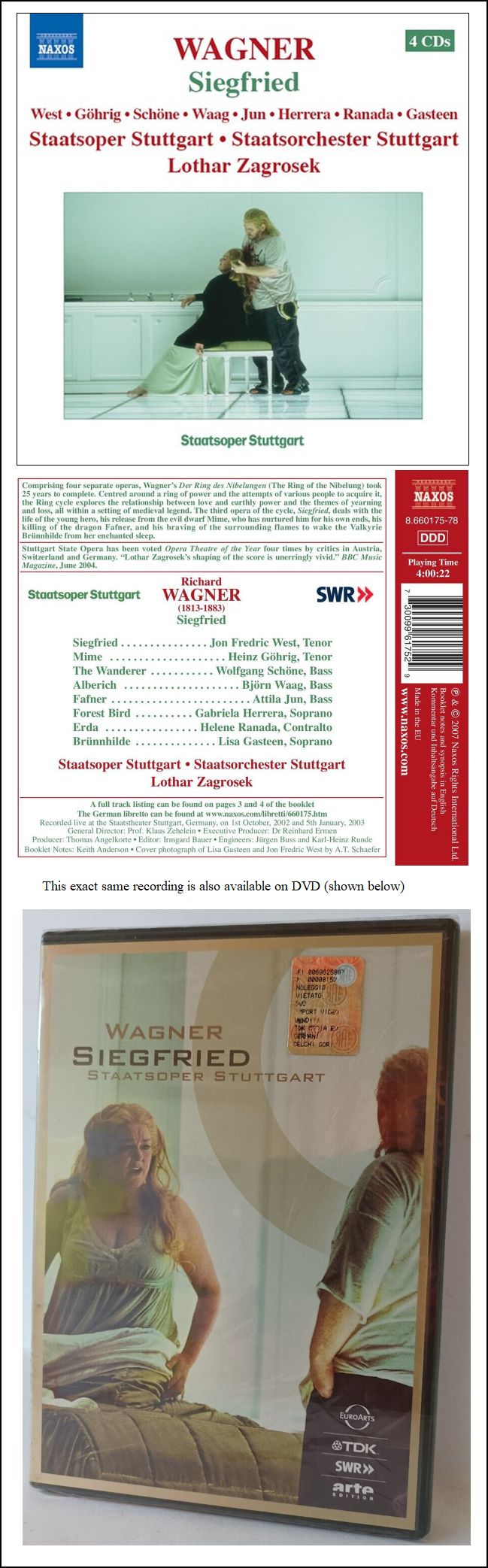

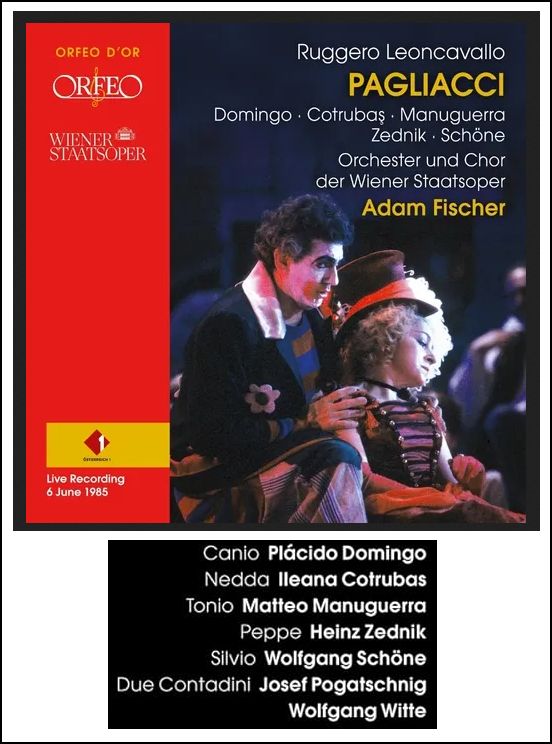

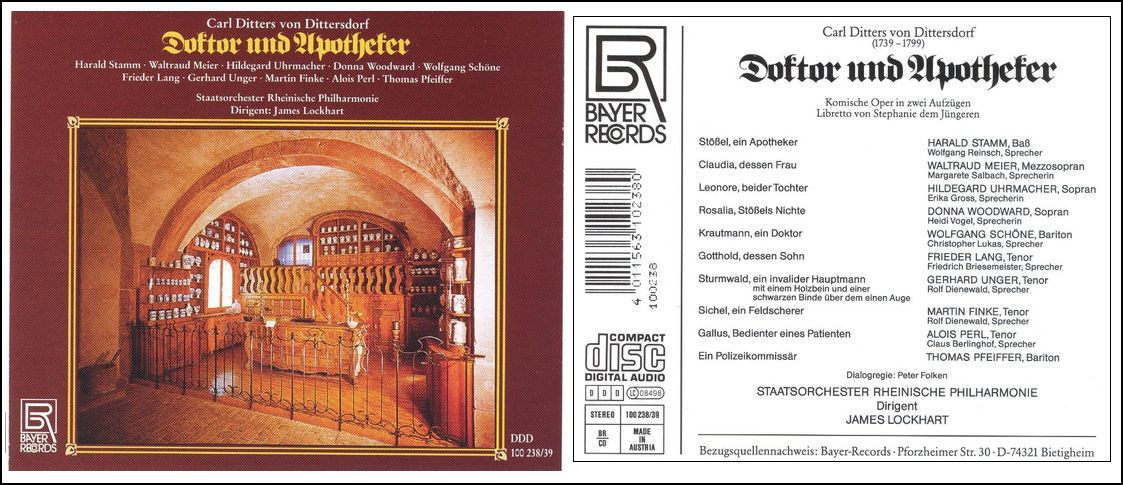

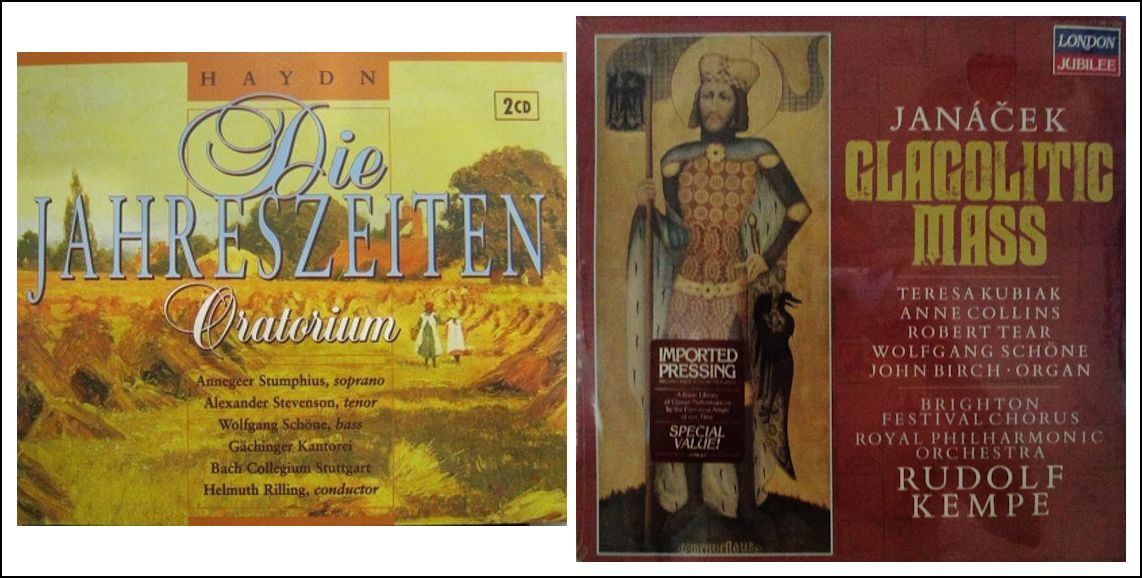

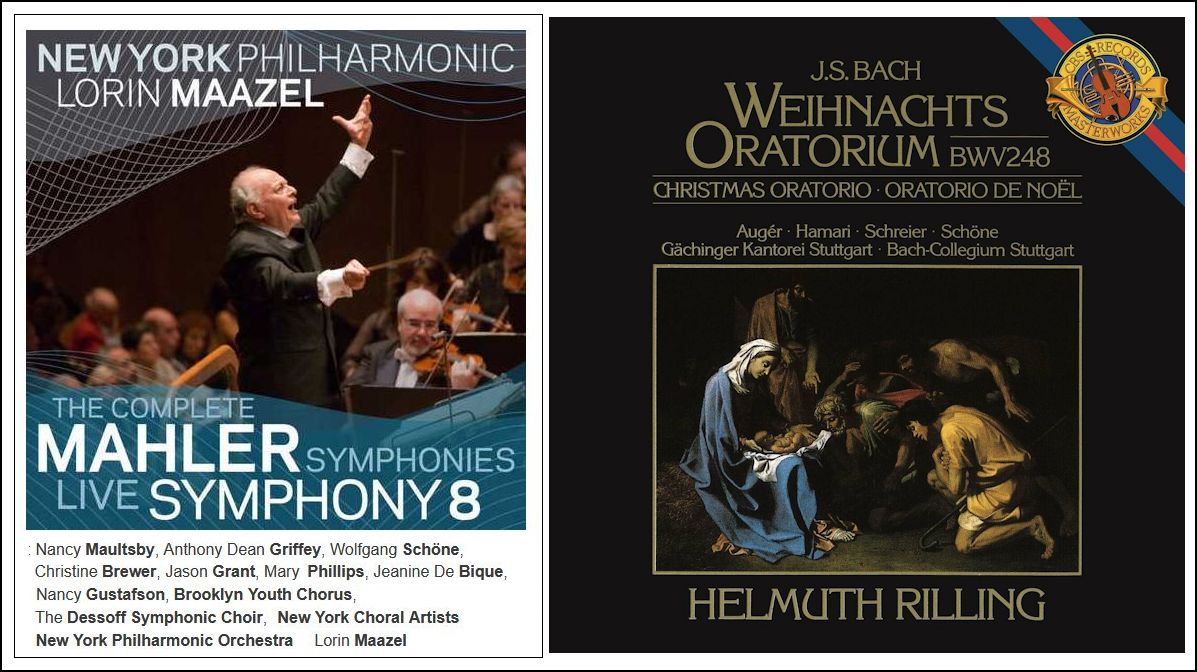

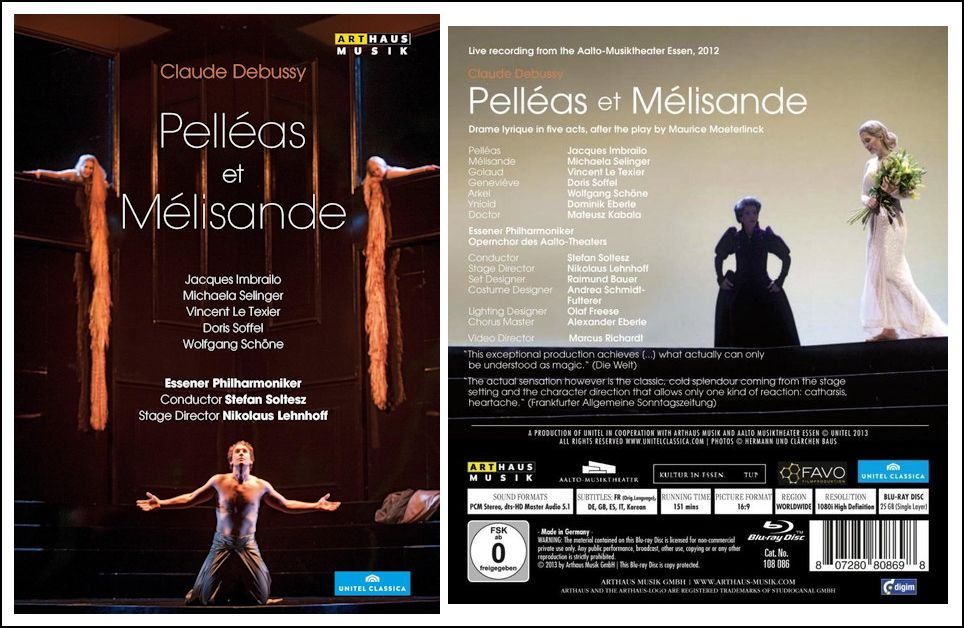

* * * * * Wolfgang Schöne (born February 9, 1940 in Bad Gandersheim, Lower Saxony) is a German baritone who made an international career in opera and concert, based at the Staatsoper Stuttgart from 1973 to 2005. He created roles in world premiered of operas, in Josef Tal's Die Versuchung at the Bavarian State Opera in 1976, in Hermann Reutter's Hamlet in Stuttgart in 1980, in Henze's Die englische Katze at the Schwetzingen Festival in 1983 and K. in Aribert Reimann's Das Schloß at the Deutsche Oper Berlin in 1992. Schöne first worked as a primary school teacher, and then began his studies of voice at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hannover with Naan Põld in 1964. He moved with him to the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg in 1986, achieving his diplomas as a concert singer and music teacher in 1969. He first performed recitals and concerts, touring internationally. Schöne made his debut as an opera singer in 1970 the role of Ottokar in Weber's Der Freischütz at the Eutin Festival. He was engaged at the Stadttheater Lübeck and at the Wuppertal Opera. After performing the role of Guglielmo in Mozart's Così fan tutte as a guest, he was engaged at the Staatstheater Stuttgart in 1973, remaining a member until 2005. He was awarded the title Kammersänger in 1978 and became an honorary member of the Staatsoper Stuttgart in 2007. Schöne appeared regularly at the Vienna State Opera from 1974

to 1993. In 1976, he performed the role of Chorèbe

in Les Troyens by Berlioz, conducted by Gerd Albrecht. Schöne appeared regularly at the

Salzburg Festival where his roles included Almaviva in Mozart's Le nozze

di Figaro (1985–1987, 1990) and Alidoro in Rossini's La Cenerentola

(1988–1989). He sang there in a 1988 concert performance of Gottfried von

Einem's Der Prozeß and in 2002 the role of Gyges in Zemlinsky's

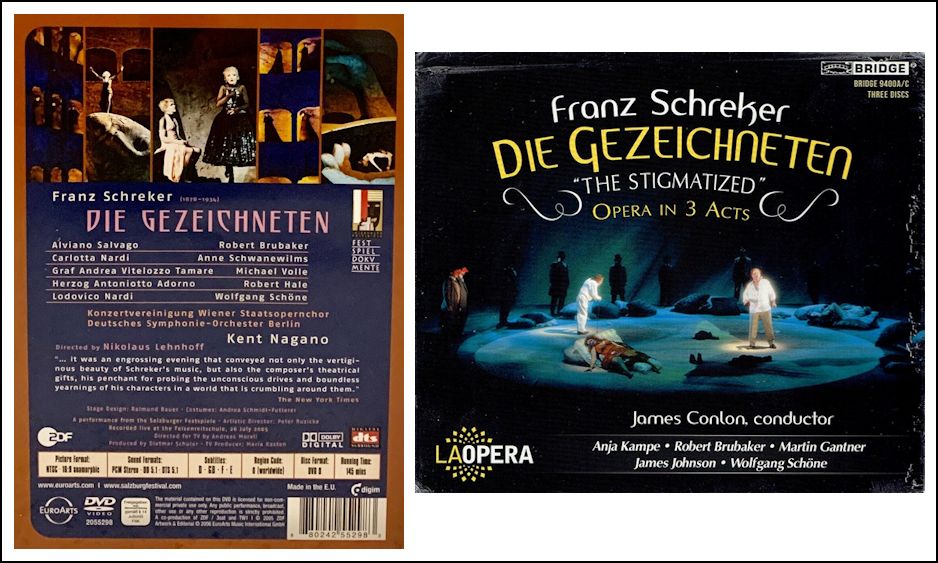

Der König Kandaules, conducted by Kent Nagano. In 2005 he appeared as Ludovico Nardi

in Schreker's Die Gezeichneten, conducted by Nagano, in a production

that was recorded as DVD, and in 2010 a production by the LA Opera, led

by James Conlon, and

released on CD. [Both are shown below]

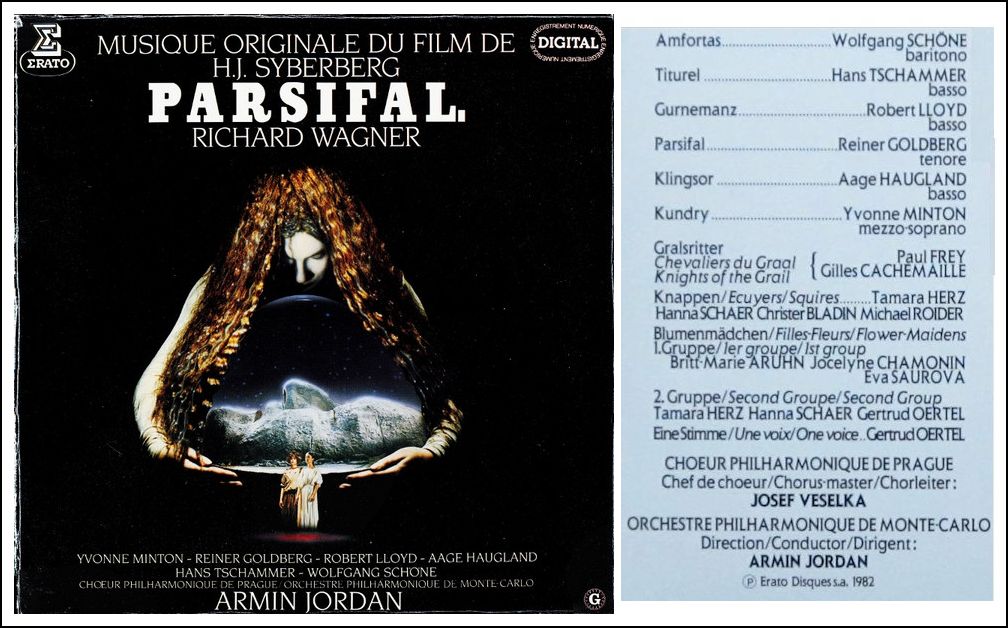

Schöne was a guest at the Semperoper in Dresden in 1999 as Barak in Die Frau ohne Schatten by Richard Strauss and in 2000 in the title role of Wagner's Der fliegende Holländer. In 2002 he performed for the first time the role of Hans Sachs in Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, at the Hamburg State Opera. In 2003 he portrayed Moses in Schoenberg's Moses und Aron in Stuttgart. In 2008, he first performed as Scarpia in Puccini's Tosca in Stuttgart. In 2009, he appeared at the Semperoper as Der alte Mann (The old man) in Henze's L'Upupa und der Triumph der Sohnesliebe. Schöne took part in world premieres of Josef Tal's Die Versuchung

in 1976 at the Bavarian State Opera, and Hermann Reutter's Hamlet

in 1980 in Stuttgart. He also created the role of Tom, Minette's

lover in Henze's Die englische Katze, with Inga Nielsen as Minette,

at the Schwetzingen Festival in 1983, and the leading role of K. in Aribert

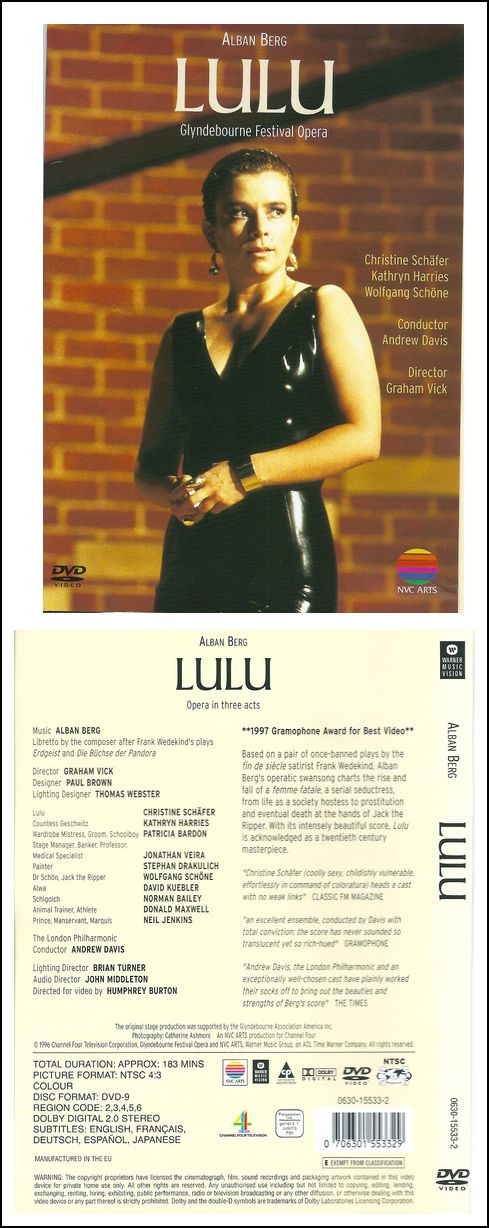

Reimann's Das Schloß in 1992 at the Deutsche Oper Berlin. Schöne performed at international opera houses as Dr. Schön in Berg's Lulu in 1996 at the Glyndebourne Festival and in 1998 at the Opéra Bastille, as well as Chicago Lyric Opera in 2008. He sang Barak in Die Frau ohne Schatten in 2000 at the Liceu in Barcelona, and Amfortas in Wagner's Parsifal in 2003 and 2004 at La Fenice in Venice. He also sang this role in Hans-Jürgen Syberberg's film, although he did not appear on screen. == Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

See my interviews with Nancy Maultsby, Nancy Gustafson, and

Lorin Maazel

© 2008 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 20, 2008. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.