Sandra Walker Brown, 75, of Augusta,

GA passed away on August 3, 2022 in Augusta. Sandra was born in Richmond,

VA to Phillip Loth Walker and Mary Jane Behymer on October 1, 1946.

She graduated from Sanford Central High School in Sanford, NC in 1964

and from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG) in 1969

with a Bachelor of Music in Performance. She later studied at the Manhattan

School of Music where she met her husband and fellow opera singer

Melvin Brown.

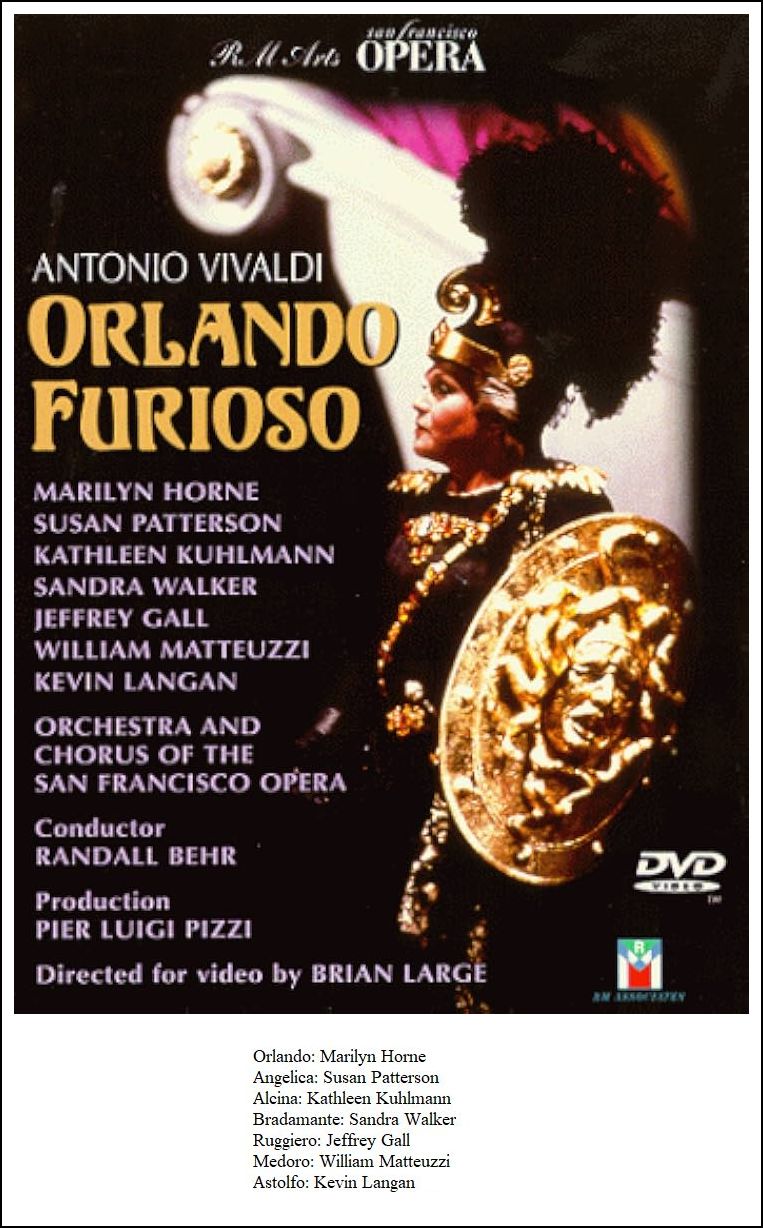

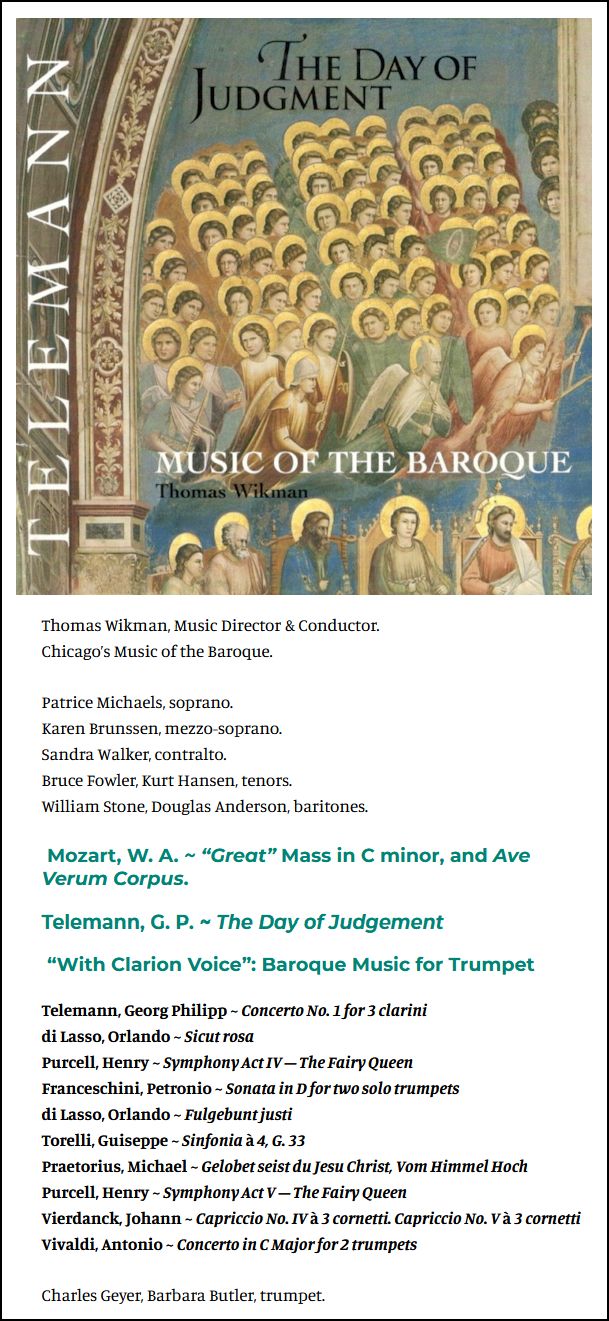

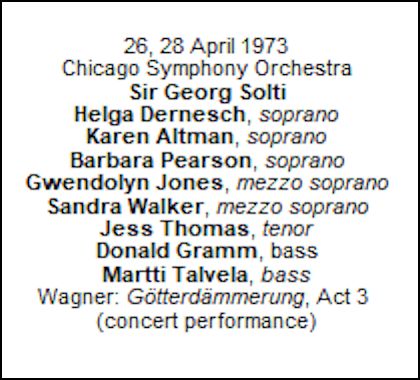

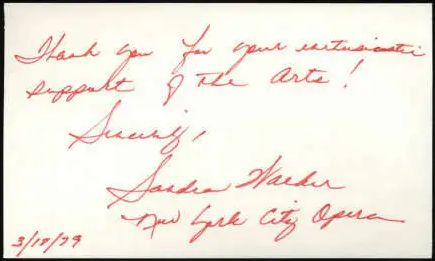

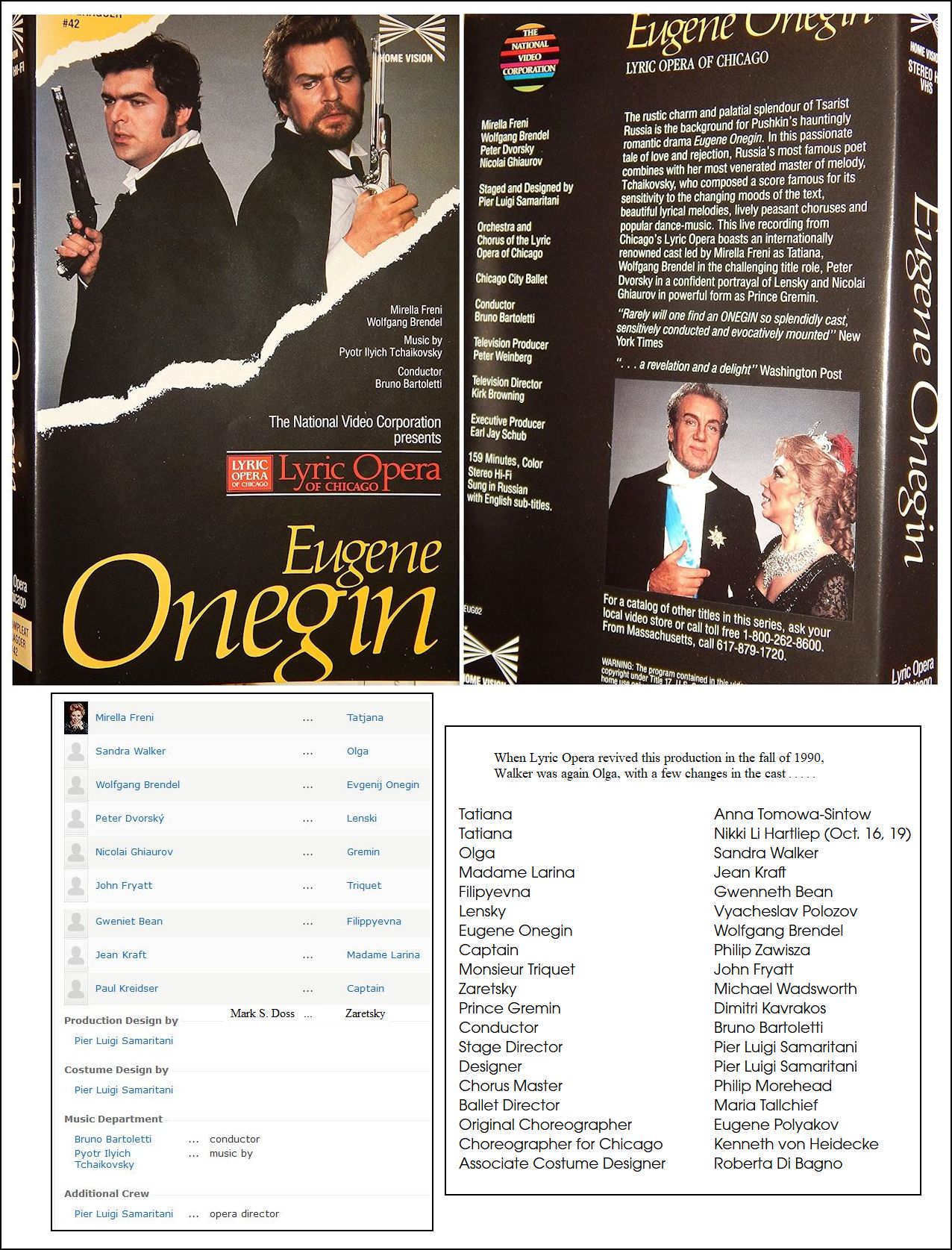

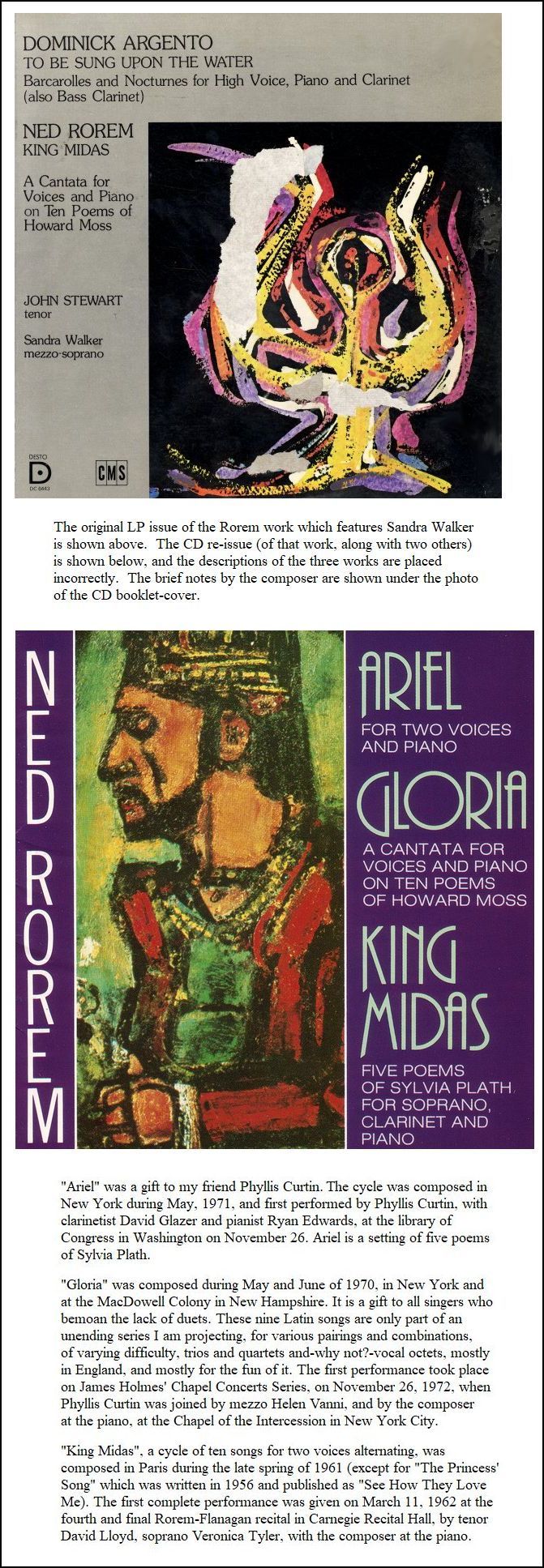

While a student at UNCG, Sandra participated in a performance of 'Messiah' at the National Cathedral in Washington DC, the result of placing third in the Friday Morning Music Club competition. Fellow Augustan Jessye Norman placed first. Still, it was Sandra that National Symphony Orchestra Howard Mitchell tagged to perform with the orchestra. Soon, Sandra, still a young performer, found herself a mezzo-in-demand, performing roles with the Metropolitan Opera in New York, the Chicago Lyric Opera, the San Francisco Opera and the New York City Opera where she often performed with Beverly Sills. She appeared with many regional opera companies and orchestras in the US and Canada, including the Virginia Opera, Baltimore Opera, Montreal Opera, Augusta Opera, Richmond Symphony, and Boston Symphony. Notable roles included Micah in Handel's 'Samson' which she performed with the Chicago Lyric, San Francisco Opera, and was her debut at the Met, and Olga in 'Eugene Onegin' with Mirella Freni at the Chicago Lyric, San Francisco Opera and the Met. She also performed the title role in 'Carmen' with the New York City Opera, Bradamante in Vivaldi's 'Orlando Furioso' (San Francisco Opera) and Maddalena in 'Rigoletto' for the Met. Over the course of her career, she also performed in Geissen, Gelsenkirchen and Frankfurt in Germany where she lived with her husband and gave birth to their son, Noel. In 1983 She was a featured performer at Spoleto Festival Italy, performing the title role in 'Rape of Lucretia' by Britten. She continued to perform after settling in Augusta, GA in 1988, appearing in concerts and operas with symphonies and companies all over the world. At the same time, she found a new career as an educator. A celebrated private voice teacher and a member of the faculty at the University of Alabama Tuscaloosa, she taught the next generation of singers, and the generation after that, the many lessons she had learned on the great stages of the world. Those are the facts and figures - the status details of Sandra's life telling her biography in finite events and accomplishments. But Sandra's story is more than performances placed on a resume. Because although a gifted singer, singing was not her greatest gift. Blessed with a surplus of care, concern and charisma, she was a true influencer. Her approach to performance, her enthusiasm for music of all stripes and her unabashed affection for her students made her much more than merely an entertainer or teacher of technique. She was a true master of music, a rare individual who understood its power and used it to engage and often forever change the lives of others. She understood the mathematics of music, but she relished the magic. Sandra was preceded in death by her husband Melvin Brown. She is survived by her son Noel Christian Brown, brother Phillip Loth Walker, Jr. and spouse Patricia of Brunswick, GA, brother Robert Holton Walker of Southport, NC, sister Carolyn Walker Kopcho of Fairhope, AL, and granddaughter Eden Parker Brown. Memorials may be given to Concerts with a Cause, Music Memorials at St John UMC, the Augusta University Department of Music, or the Metropolitan Opera. A Memorial Service will be held at 11 am Saturday, August 13 at St John United Methodist Church with the Reverend Jenny Anderson of St John UMC officiating. Arrangements are by Platt's Funeral Home. == From We Remember by Ancestry (with

slight corrections)

|

|

Born in Vienna on March 20, 1941, Uwe Mund is an Austrian conductor. At the age of fourteen he gave his first concert as solo pianist, and at sixteen he began his studies as a conductor and composer. At the age of twenty he became conductor of the Vienna Boys' Choir, with which he toured Europe and America. He also conducted the Viennese Hofmusikkapelle, a court orchestra dating back to the Middle Ages. He became solo répétiteur for the Vienna State Opera, and assistant conductor of the Wiener Singverein in 1963. He was music director at Musiktheater im Revier in Gelsenkirchen from 1977 until 1988, where his work and passion are considered to have defined an era. He was music director at Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona, from 1987

until 1994, and from 1998 at the Kyoto Symphony Orchestra. He was also guest

conductor at numerous other (opera) houses. He made several CD and video recordings. |

|

Hans Zender (November 22, 1936 in Wiesbaden - October 22, 2019 in Meersburg) attended the Maifestspiele at age 13, listening to concerts conducted by Carl Schuricht, Karl Böhm and Günter Wand, among others. He took piano lessons and learned to play the organ. From 1949, he went each year to the Darmstädter Ferienkurse, where he got to know trends in new music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Olivier Messiaen and John Cage. He studied piano, conducting, and composition (the latter with Wolfgang Fortner) at the Hochschule für Musik Frankfurt and the Hochschule für Musik Freiburg from 1956 to 1959. He was trained as a concert pianist by Edith Picht-Axenfeld.

Zender's opera Stephen Climax, with his own libretto based on James Joyce and Hugo Ball, was premiered on 15 June 1986 at the Oper Frankfurt, staged by Alfred Kirchner and conducted by Peter Hirsch. His third opera, Chief Joseph, was premiered in June 2005 at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden, staged by Peter Mussbachand conducted by Johannes Kalitzke. From 1988 until 2000, Zender taught composition at the Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst in Frankfurt. Among his students was Isabel Mundry. Invited by Walter Fink, he was in 2011 the 21st composer featured in the annual Komponistenporträt of the Rheingau Musik Festival. Music in a chamber concert included denn wiederkommen (Hölderlin lesen III) for string quartet and speaking voice (1991) and Mnemosyne (Hölderlin lesen IV) for female voice, string quartet, and tape (2000), performed by Salome Kammer and the Athena Quartet. A symphony concert was given by the SWR Vokalensemble and SWR Symphonieorchester conducted by Emilio Pomàrico, including Schubert-Chöre, featuring Zender's adaptations of four Schubert choral works with orchestral rather than the original piano accompaniment, written in the 1980s. |

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 23, 1985. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.