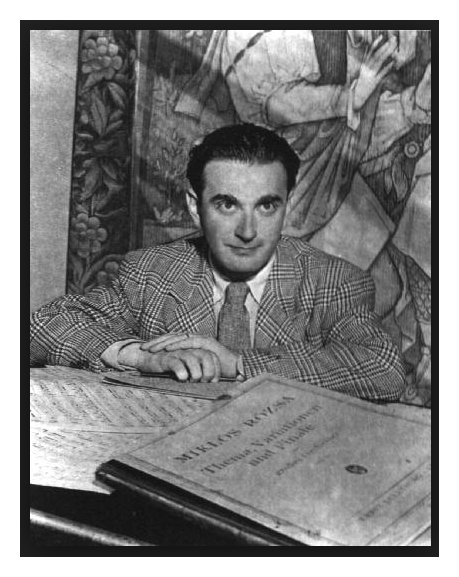

| Miklós Rózsa is the

composer most closely identified with noir. He was a Hungarian-born composer

trained in Germany, and active in France, war-time Britain, and later in

the United States, with extensive sojourns in Italy, during a career spanning

more than 60 years (1931-1995). His music was at times Wagnerian, brooding

and atmospheric, conveying the dark moods of noir, and at other times frenetic

and electrifying, suggesting the fast pace of modern urban existence. These

contrasts are clearly evident in his score for Double Indemnity. Rózsa won Academy Awards for two noir scores, Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945), and A Double Life (1947), the story of a deranged stage actor who becomes obsessed with his role as Othello. Ironically, Rózsa once described his musical career as a “double life” because, although he composed more than one hundred film scores, he maintained a steadfast allegiance to absolute concert music throughout his career. -- From a website about Film Noir

|

BD: This is Bruce Duffie, calling from Chicago.

BD: This is Bruce Duffie, calling from Chicago. BD: So it would be the plot of the film, rather than the actors

themselves?

BD: So it would be the plot of the film, rather than the actors

themselves? MR: No, no, no, no. My concerti were. The first

concerto was, the one I wrote for Heifetz. Then I wrote a double concerto

[Sinfonia Concertante, Op. 29] for

Heifetz and Piatigorsky. Then I wrote a piano concerto for Leonard

Pennario, and then came a cello concerto for János Starker,

and finally the viola concerto for Pinchas Zukerman.

MR: No, no, no, no. My concerti were. The first

concerto was, the one I wrote for Heifetz. Then I wrote a double concerto

[Sinfonia Concertante, Op. 29] for

Heifetz and Piatigorsky. Then I wrote a piano concerto for Leonard

Pennario, and then came a cello concerto for János Starker,

and finally the viola concerto for Pinchas Zukerman. MR: No, Hans Lange. [Hans Lange (1884-1960), associate

conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1936 to 1943, conductor

of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1943 to 1946] It was Theme, Variations and Finale. Later

[in 1942] he conducted the Three Hungarian

Sketches [and also the Concerto

for String Orchestra in 1945]. It was actually Stock who accepted

the pieces, but he asked Lange to conduct. Later my Sinfonia Concertante was given with Victor Aitay and Frank

Miller. [Victor Aitay (1921-2012) served the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

for fifty seasons as assistant concertmaster (1954-1965), associate concertmaster

(1965-1967), concertmaster (1967-1986), and concertmaster emeritus (1986-2003);

Frank Miller (1912-1986) served as principal cellist for the NBC Symphony

Orchestra conducted by Toscanini (1940-1954) and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

(1959-1960 and 1961-1985)] The conductor was Martinon. A couple

of years later the same soloists repeated it with Leinsdorf. Then

Sir Georg Solti conducted

my Cello Concerto with János

Starker [November, 1971]. So Chicago is very dear to me. [In

addition to his legendary international performing and recording career,

Starker was principal cellist of the CSO from 1953-1958. It's a great

orchestra, and now you have a really great conductor.

MR: No, Hans Lange. [Hans Lange (1884-1960), associate

conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1936 to 1943, conductor

of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1943 to 1946] It was Theme, Variations and Finale. Later

[in 1942] he conducted the Three Hungarian

Sketches [and also the Concerto

for String Orchestra in 1945]. It was actually Stock who accepted

the pieces, but he asked Lange to conduct. Later my Sinfonia Concertante was given with Victor Aitay and Frank

Miller. [Victor Aitay (1921-2012) served the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

for fifty seasons as assistant concertmaster (1954-1965), associate concertmaster

(1965-1967), concertmaster (1967-1986), and concertmaster emeritus (1986-2003);

Frank Miller (1912-1986) served as principal cellist for the NBC Symphony

Orchestra conducted by Toscanini (1940-1954) and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

(1959-1960 and 1961-1985)] The conductor was Martinon. A couple

of years later the same soloists repeated it with Leinsdorf. Then

Sir Georg Solti conducted

my Cello Concerto with János

Starker [November, 1971]. So Chicago is very dear to me. [In

addition to his legendary international performing and recording career,

Starker was principal cellist of the CSO from 1953-1958. It's a great

orchestra, and now you have a really great conductor. MR: Yes. Of course there is a lot of music which is un-understandable

for the people, but it was always like that. When I came to this country

in 1940, John Barbirolli was a friend of mine, and he told me that when he

played the Music for Strings Percussion

and Celesta by Bartók, half of the audience went out.

He was so mad that the next week they repeated it! [Both laugh]

MR: Yes. Of course there is a lot of music which is un-understandable

for the people, but it was always like that. When I came to this country

in 1940, John Barbirolli was a friend of mine, and he told me that when he

played the Music for Strings Percussion

and Celesta by Bartók, half of the audience went out.

He was so mad that the next week they repeated it! [Both laugh] MR: Oh, that's up to the conductor. The conductor should

take enough time to examine the works which have been sent to him.

Every conductor gets, I would say, up to hundred new compositions every year.

Now to ask a conductor who conducts in Europe and in America to take the

time to look over all these works, it's impossible. He should have

maybe an assistant who looks them over. I remember one summer, Eugene

Ormandy stayed here when he conducted in Hollywood Bowl. I went over

to him every day, and on his piano were, oh, fifty or sixty new works.

He said, "Would you help me?" and I said, "Of course." We spent about

an hour or two and looked over what was good and what should be played, and

what should be rejected. So it's up to the conductor to choose the

good music.

MR: Oh, that's up to the conductor. The conductor should

take enough time to examine the works which have been sent to him.

Every conductor gets, I would say, up to hundred new compositions every year.

Now to ask a conductor who conducts in Europe and in America to take the

time to look over all these works, it's impossible. He should have

maybe an assistant who looks them over. I remember one summer, Eugene

Ormandy stayed here when he conducted in Hollywood Bowl. I went over

to him every day, and on his piano were, oh, fifty or sixty new works.

He said, "Would you help me?" and I said, "Of course." We spent about

an hour or two and looked over what was good and what should be played, and

what should be rejected. So it's up to the conductor to choose the

good music.

BD: So then if anyone 100 years from now was to go back and

try and find the original version, you would not want that?

BD: So then if anyone 100 years from now was to go back and

try and find the original version, you would not want that? MR: Well, let's face it, the main thing you compose film music

for is money. I had no idea about film music. I was living in

Paris, and I gave an evening of chamber music together with my friend Arthur

Honegger. It was in a wonderful but small room in the hall, I would

say two or three hundred people. But it was full, and Honegger wanted

to help me, so it had my Sonata for two

violins his Sonata for two violins,

and some of my piano pieces played by Clara Haskil. It was a big success,

and after that he said, "Let's go have dinner. We earned, altogether,

about fifteen or sixteen dollars." I said, "Is that all we earned???"

and he said, "Yes, of course! We had to pay for the hall, for the artists

and publicity. So we have about fifteen dollars, and I will invite

you for dinner!" So I said, "I am young; nobody knows me in Paris,

but you're a great master. How do you make a living if that's all you

can make with a concert?" and he said, "I write film music." I said,

"This is impossible. Do you write foxtrots?" He said, "No, I

don't write foxtrots. I write serious film music." I asked if

I could hear some of it and he told me that Les Misérables was playing on

the Grands Boulevards. I went the next day and I was absolutely flabbergasted.

It was really Honeggerian music, very serious, and it was a great film.

I called immediately and I told him, "That's absolutely wonderful.

Could I do the same?" and he said, "Yes, of course you could, but how?

No producer is going to accept you because you did not write any film music

before!" If you say that you wrote a sonata for two violins, they are

not interested. So I gave it up and went to London. It was 1935

and I wrote a ballet, Hungaria, for

Markova and Dolin and company. I read in the paper that a friend of

mine, Jacques Feyder — a very well known film director

who was Belgian, actually, not French — was

in town. So I called him up and he said, "I am glad you're here.

Can you come and help me? How far are you from the hotel?" I

told him I was about ten minutes away and asked what was the matter.

He said, "I want to give out my laundry for tomorrow, and these idiots don't

understand French. Could you explain it to them?" I said I could

explain, and everything was fine. He asked me to go to dinner, but

I told him I could not because my ballet was being given and I had to let

them know how everything was going. He said he didn't know I had written

a ballet and asked if he could come. He came and he was delighted.

He invited to me in a nightclub, and it was the first time I had been in

a nightclub. He ordered dinner and a bottle of champagne. Now

I don't drink, so he drank the champagne, and as the champagne went down,

his estimation of me went up. [Both laugh] He ordered a second

bottle of champagne and drank it. By that time he felt I was the greatest

composer of the world and said, "You're going to write the music of my film."

I told him I had never did that, but he said [firmly], "Never mind.

I heard your music; that's enough. Tomorrow, my wife, Françoise

Rosay, is coming from Paris, and you will come for lunch." I went to

lunch and she was a very charming lady. It was one 1:00 and we were

waiting to eat. It got to be 1:30, then 2:00 and still no lunch.

I asked about this and Feyder said, "Oh, she is late." I had no idea

who "she" was. Finally, at 2:30, a very elegant lady with beautiful

hat and a gentleman arrived, and they were introduced as Mr. and Mrs. Sieber.

Both had German accents. Mrs. Sieber was sitting on my right, my friend

Feyder was on my left. Suddenly Mrs. Sieber said to me, "Is my song

ready?" I asked, "What song?" and she continued, "Monsieur Feyder told

me that you were going to write the music for our film." I turned to

Feyder and said sotto voce, "Who

is she?" and he said, "You idiot! That is Marlene Dietrich!"

She was married to Mr. Sieber. [Both laugh] Later he said, "Now

we are going to the studio of Mr. Korda," and I said, "Who is Mr. Korda?"

He said, "You are an idiot. He's Hungarian! He's the head of

London Films." We went to the new Denham Studios, and a half an hour

later he came back to say, "You are engaged." That was the first film,

Knight Without Armour, with Marlene

Dietrich and Robert Donat, directed by Jacques Feyder 1937. So when

you ask whether a composer should write both, I say yes if they can.

If they need the money, the film pays it. With the serious music you

earn very little. If you have the luck, as I had, then it's fine.

Also it is necessary if they have a dramatic talent. Not every composer

would be good for film music. For instance, a composer I estimate very

highly and really appreciate, is Hindemith. He would be impossible

as a film composer, and he never tried it. [Hindemith wrote music for

Hans Richter's 1928 avant-garde/dadaist animated 9-minute film Ghosts Before Breakfast (Vormittagsspuk), the soundtrack for which

was destroyed by the Nazis.]

MR: Well, let's face it, the main thing you compose film music

for is money. I had no idea about film music. I was living in

Paris, and I gave an evening of chamber music together with my friend Arthur

Honegger. It was in a wonderful but small room in the hall, I would

say two or three hundred people. But it was full, and Honegger wanted

to help me, so it had my Sonata for two

violins his Sonata for two violins,

and some of my piano pieces played by Clara Haskil. It was a big success,

and after that he said, "Let's go have dinner. We earned, altogether,

about fifteen or sixteen dollars." I said, "Is that all we earned???"

and he said, "Yes, of course! We had to pay for the hall, for the artists

and publicity. So we have about fifteen dollars, and I will invite

you for dinner!" So I said, "I am young; nobody knows me in Paris,

but you're a great master. How do you make a living if that's all you

can make with a concert?" and he said, "I write film music." I said,

"This is impossible. Do you write foxtrots?" He said, "No, I

don't write foxtrots. I write serious film music." I asked if

I could hear some of it and he told me that Les Misérables was playing on

the Grands Boulevards. I went the next day and I was absolutely flabbergasted.

It was really Honeggerian music, very serious, and it was a great film.

I called immediately and I told him, "That's absolutely wonderful.

Could I do the same?" and he said, "Yes, of course you could, but how?

No producer is going to accept you because you did not write any film music

before!" If you say that you wrote a sonata for two violins, they are

not interested. So I gave it up and went to London. It was 1935

and I wrote a ballet, Hungaria, for

Markova and Dolin and company. I read in the paper that a friend of

mine, Jacques Feyder — a very well known film director

who was Belgian, actually, not French — was

in town. So I called him up and he said, "I am glad you're here.

Can you come and help me? How far are you from the hotel?" I

told him I was about ten minutes away and asked what was the matter.

He said, "I want to give out my laundry for tomorrow, and these idiots don't

understand French. Could you explain it to them?" I said I could

explain, and everything was fine. He asked me to go to dinner, but

I told him I could not because my ballet was being given and I had to let

them know how everything was going. He said he didn't know I had written

a ballet and asked if he could come. He came and he was delighted.

He invited to me in a nightclub, and it was the first time I had been in

a nightclub. He ordered dinner and a bottle of champagne. Now

I don't drink, so he drank the champagne, and as the champagne went down,

his estimation of me went up. [Both laugh] He ordered a second

bottle of champagne and drank it. By that time he felt I was the greatest

composer of the world and said, "You're going to write the music of my film."

I told him I had never did that, but he said [firmly], "Never mind.

I heard your music; that's enough. Tomorrow, my wife, Françoise

Rosay, is coming from Paris, and you will come for lunch." I went to

lunch and she was a very charming lady. It was one 1:00 and we were

waiting to eat. It got to be 1:30, then 2:00 and still no lunch.

I asked about this and Feyder said, "Oh, she is late." I had no idea

who "she" was. Finally, at 2:30, a very elegant lady with beautiful

hat and a gentleman arrived, and they were introduced as Mr. and Mrs. Sieber.

Both had German accents. Mrs. Sieber was sitting on my right, my friend

Feyder was on my left. Suddenly Mrs. Sieber said to me, "Is my song

ready?" I asked, "What song?" and she continued, "Monsieur Feyder told

me that you were going to write the music for our film." I turned to

Feyder and said sotto voce, "Who

is she?" and he said, "You idiot! That is Marlene Dietrich!"

She was married to Mr. Sieber. [Both laugh] Later he said, "Now

we are going to the studio of Mr. Korda," and I said, "Who is Mr. Korda?"

He said, "You are an idiot. He's Hungarian! He's the head of

London Films." We went to the new Denham Studios, and a half an hour

later he came back to say, "You are engaged." That was the first film,

Knight Without Armour, with Marlene

Dietrich and Robert Donat, directed by Jacques Feyder 1937. So when

you ask whether a composer should write both, I say yes if they can.

If they need the money, the film pays it. With the serious music you

earn very little. If you have the luck, as I had, then it's fine.

Also it is necessary if they have a dramatic talent. Not every composer

would be good for film music. For instance, a composer I estimate very

highly and really appreciate, is Hindemith. He would be impossible

as a film composer, and he never tried it. [Hindemith wrote music for

Hans Richter's 1928 avant-garde/dadaist animated 9-minute film Ghosts Before Breakfast (Vormittagsspuk), the soundtrack for which

was destroyed by the Nazis.]

Miklos Rozsa, 88, Composer of Film Music

By RICHARD SEVERO Published in The New York Times, July 29, 1995 Miklos Rozsa, whose opulent scores for some of Hollywood's most lavish epics earned him three Academy Awards, died at Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles on Thursday. He was 88. He had suffered a stroke about three weeks ago and been put on life support, family members told the Associated Press. Mr. Rozsa was known for doing meticulous research before composing for his films, which included "The Four Feathers" (1939), "The Thief of Baghdad" (1940), "Jungle Book" (1942), "Quo Vadis" (1951), "Ivanhoe" (1952), "Julius Caesar" (1953), "Ben-Hur" (1959) and "El Cid" (1961). The re-creation of ancient music was his most difficult challenge, since only the most fragmentary suggestions remained of what the ancients listened to. So for "Quo Vadis" he had nonfunctioning copies of ancient Roman instruments made, then tried to imagine how they might have sounded. And for "Ben Hur," he went to Rome and stood on Palatine Hill, trying to imagine what had happened on the Via Sacra 2,000 years earlier. "I began to whistle scraps of ideas and to march about excitedly and rhythmically," he recalled years later. "Two young girls looked at me in terror and fled, muttering 'pazzo' " -- which means "madman" -- but of my lunacy was born 'Parade of the Charioteers,' which is now played at football matches and university festivities all over America." Mr. Rozsa was so prolific that he frequently competed against himself for honors. In 1945, for example, he won his first Oscar for the score for "Spellbound," but would have preferred winning the award for his music for "The Lost Weekend," nominated at the same time. Mr. Rozsa said he felt "The Lost Weekend" had "the stronger score." Both scores used large studio orchestras and featured the theremin, an early electronic instrument that wailed like a cross between a neurotic contralto and a frightened viola. He was awarded his second Oscar for "A Double Life" (1947) and his third for the music for "Ben-Hur" (1959). Although best known for his movie music, Mr. Rozsa also composed many works for the concert hall, including tone poems, rhapsodies, variations and concertos, many of them reflecting his interest in the folk music of his native Hungary. His Concerto for Violin was given its premiere in 1956 by Jascha Heifetz. His Sinfonia Concertante for violin, cello and chamber orchestra was written in 1966 for the cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. Mr. Rozsa was born in Budapest on April 18, 1907. His father was a successful land-owning industrialist who ran unsuccessfully for Parliament. His mother, born in Budapest, aspired to be a concert pianist and studied at the Budapest Academy before her marriage. Young Miklos started composing music and playing the violin when he was 5 years old. Although he showed considerable talent, his father strongly suggested that he study chemistry at the University of Budapest. The son dutifully complied, but he studied at the Music Conservatory at the same time. Later, after his father relented, he went to Leipzig, Germany, and studied composition and violin. In 1931 he went to Paris, where he wrote some chamber music that won the approval of the composer Arthur Honegger. In the late 1930's Mr. Rozsa was introduced to Alexander Korda, a fellow Hungarian who had established London Films with his brothers, Vincent and Zoltan, and was achieving considerable success. Alexander Korda commissioned Mr. Rozsa, who had seen few movies and hadn't the slightest idea how to write a score, to create the music for "Knight Without Armor," a 1937 film starring Marlene Dietrich and Robert Donat. At about the same time, Akos Tolnay, a script writer who was also Hungarian, asked Mr. Rozsa to score another movie, "Thunder in the City." He scoured bookshops on Charing Cross Road for works on film music and managed to write the two scores. After that, commissions came quickly. In the years that followed he produced scores for such well-received films as "Five Graves to Cairo," "Sahara" and "So Proudly We Hail" (all 1943); "Double Indemnity" (1944); "A Song to Remember" and "Blood on the Sun" (both 1945); "The Killers" and "The Strange Love of Martha Ivers" (both 1946); "The Red House" and "Brute Force" (both 1947), and "The Naked City" and "Criss Cross" (both 1948). Among the other films for which he created scores were "The Asphalt Jungle" (1950), "Something of Value" (1957), "The V.I.P.'s" (1963), "The Green Berets" (1968), "Time After Time" (1979), and "Eye of the Needle" (1981). Mr. Rozsa married the former Margaret Finlason in 1943 and dedicated his Concerto for Strings to her. She survives him, as do a daughter, Juliet Rozsa-Brown of West Los Angeles; a son, Nicolas, of San Francisco; a sister, Edith Jankay of Redlands, Calif., and three granddaughters. |

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on June 27, 1987.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, 1992 and 1997. A copy of the

unedited audio was placed in the Archive

of Contemporary Music at Northwestern

University, and also in the Rozsa

Archives. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on

this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.