Bass Jan - Hendrik Rootering

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Jan-Hendrik Rootering (born 18 March

1950 in Wedingfeld near Flensburg) is an operatic bass, son of the Dutch

tenor Hendrikus Rootering from whom he had his first lessons. After further

study at Hamburg's Musikhochschule he began singing minor roles

with the Staatsoper Hamburg and made a debut at the Bayerischen Staatsoper

München in 1982 as the Spirit Messenger in Die Frau ohne Schatten.

In 1987 he received the title of Bayerischer Kammersänger.

Rootering was the bass soloist in the Beethoven Ninth Symphony conducted

by Leonard Bernstein in celebration of the fall of the Berlin wall in the

no-longer-divided city of Berlin, on Christmas 1989.

|

Jan-Hendrik Rootering graced Lyric Opera of Chicago with his artistry

on three occasions, all of which are enumerated in the course of our conversation.

However, when we met, it was in June of 1992, and he was performing

in the Symphony #8 of Mahler with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

at the Ravinia Festival. James Levine conducted,

and the other soloists were Helen Donath, Andrea Gruber, Heidi Grant

Murphy, Hitomi Katagiri, Jane Shaulis, Gary Lakes, and Bryn Terfel, along

with the Chicago Symphony Chorus, Margaret Hillis, director,

the Milwaukee Symphony Chorus, Margaret Hawkins, director, and the Chicago

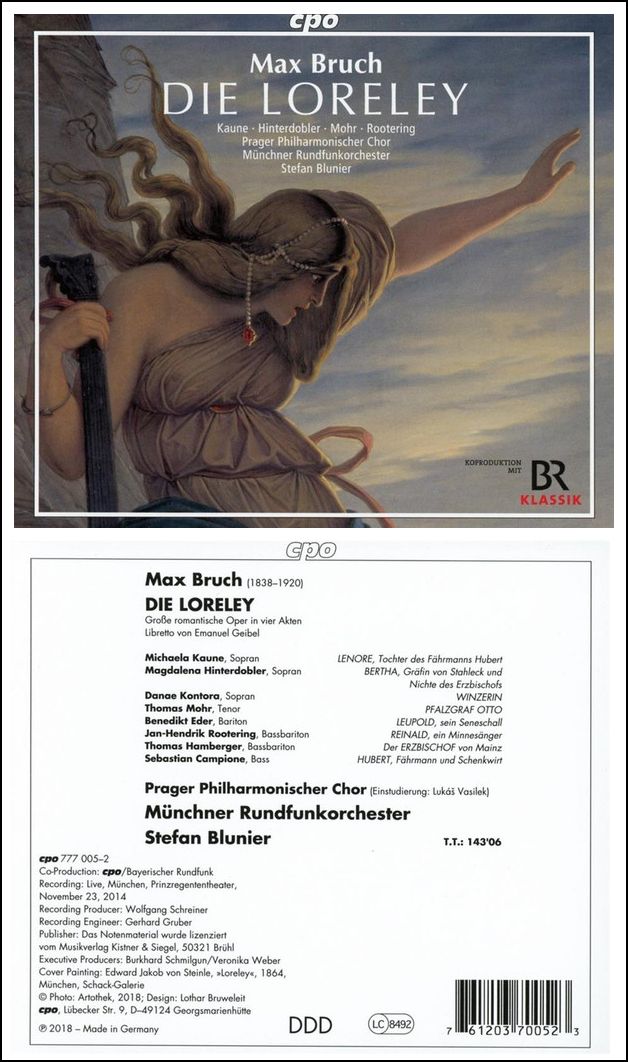

Children’s Choir, Lucy Ding, director. [As shown above, Rootering

appears in two different recordings of the Mahler 8th. Names which

are links on this page refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.]

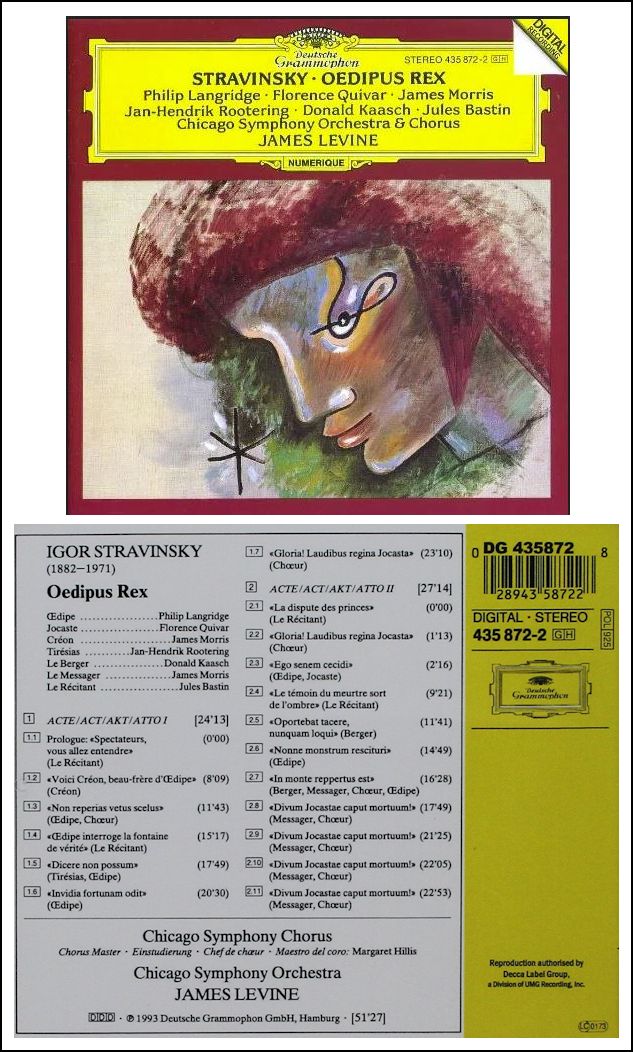

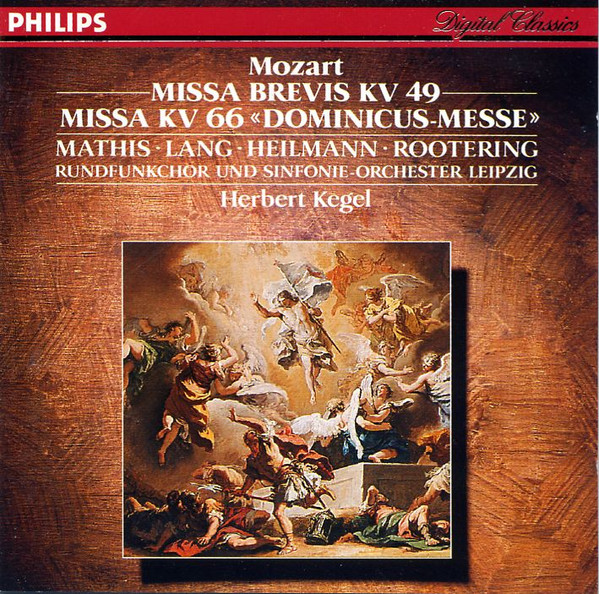

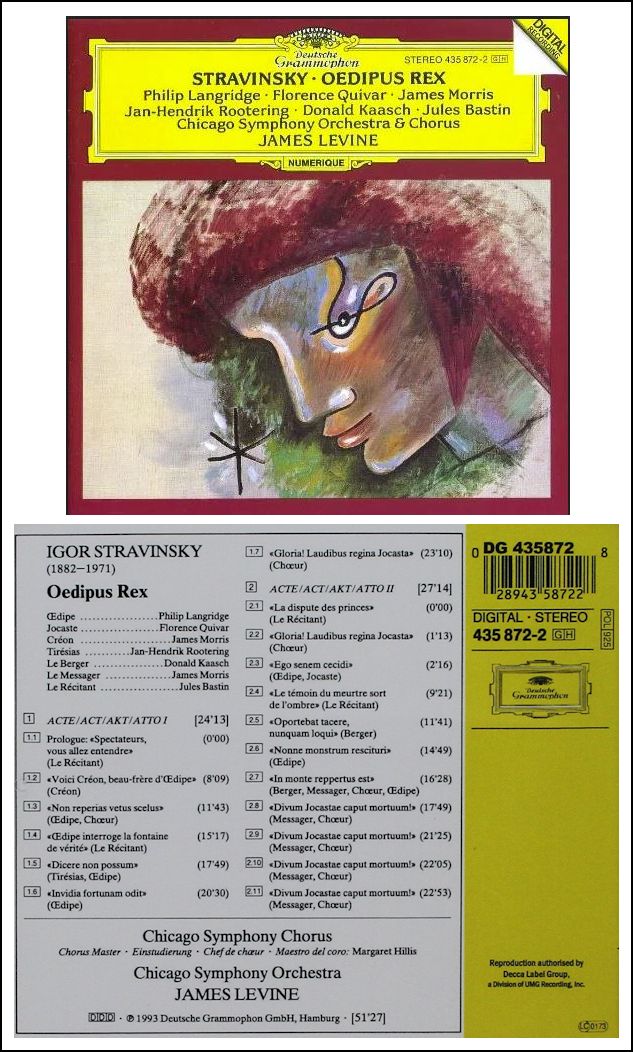

The previous year, Rootering had been in the performance and recording

of Oedipus Rex of Stravinsky (which is shown at right). [See

my interviews with Florence

Quivar, and Donald

Kaasch.]

Portions of this interview were used several times on WNIB, Classical

97, and now [2024] I am pleased to present the entire chat.

Bruce Duffie: You are both an opera and concert

singer. How do you divide your career between those very taxing

activities?

Jan-Hendrik Rootering: Actually, not at

all. I don’t think it is dividing. It’s more combining.

BD: Then how do you combine them?

Rootering: In choosing carefully what

to sing when and where, basically.

BD: [Gently pressing the point] What

goes into choosing carefully?

Rootering: You must know exactly what

kind of repertoire you sing at what point. I wouldn’t want to

sing Hans Sachs today and a Mahler Eighth Symphony tomorrow, for

instance.

BD: Would you sing a Mahler Eighth

Symphony today, and Hans Sachs tomorrow?

Rootering: No. It’s

the same thing. [Laughs]

BD: Sometimes one before the other is

different.

Rootering: Yes, but especially these pieces,

you need to have rest for the voice. That’s why I say to choose

carefully what you do and when.

BD: What about Fasolt [Rheingold]

today and Mahler Eighth tomorrow?

Rootering: That is something you could

consider.

BD: So when you’re scheduling the roles,

you make sure to have plenty of rest?

Rootering: Yes.

BD: Do you limit the number of engagements

you have year to year?

Rootering: Certainly, but it’s not limited

just by a number. It is more limited by difficulty in terms of

singing, in terms of traveling, and in terms of rehearsing.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You don’t

want to be a jet-setter?

Rootering: [Laughs] I guess everybody

who is in this business nowadays is a jet-setter to some extent, but

while you’re young, you don’t feel what it does to your body.

Even flying from New York to Chicago there is a time-difference, and

even though you don’t feel it immediately, at some point you are going

to feel it, and I don’t want end up suffering from it.

BD: Do you get jet-lag?

Rootering: Not the jet-lag at the moment,

but what it eventually does to your whole system.

BD: Oh, resetting your clock?

Rootering: Yes. That effects the

body-metabolism, and that then effects the voice, your highs and

your lows. This is not in terms of high notes and low notes,

but in terms of active highs and active lows.

BD: High and low energy?

Rootering: Yes!

BD: Do you always want to make sure that

you give the public as much energy as possible?

Rootering: Exactly!

BD: Despite this, do you like singing

in different places around the world?

Rootering: Yes. It’s wonderful to

meet a great variety of people who, most of time, always are after

the same thing. But they’re just so different, and it’s wonderful.

BD: What is it they’re after?

Rootering: Ways of making music, and getting

a wonderful product for ourselves and for the audiences.

BD: How much of music is art, and how

much of music is product?

Rootering: [Smiles] It depends on

how you look at it. All of music is art, and all of music is

product. There is the individual art of playing an instrument

in the orchestra, or singing as a soloist or in a chorus, as well as

being a conductor. Without that art, you can’t produce anything,

and without the producing factor, art is bound to go down the drain, because

if we don’t have an audience to perform for, then it’s a self-satisfying

circle, and that stops pretty soon. Plus you need the energy that

comes from the hall. You can immediately feel an outstanding performance

because it always has an outstanding audience. So it’s a give-and-take

effect. It’s not only the performers who are brilliant. The

audience is also brilliant, and then the performance is better.

BD: Then let me leap to a different situation.

How can you get that same kind of a performance on a recording, when

there is no audience to feed off of?

Rootering: That is something that you

have to learn as a professional. You have a drawer of feelings

that you have to reproduce, and I admit it’s more difficult in a cold

impersonal studio to do something like that. But it is possible.

It’s harder work, but it’s possible. It’s a lot better, and a lot

of recordings are done where you first do a couple of concerts, and then

you go to the studio and record it. Then it’s reproducing the feelings

you just had.

BD: When you’re making a recording, are

you conscious of the potential audience?

Rootering: You always have that in mind.

You always project to reach out to somebody, even if it’s just in

the imagination. There’s always somebody there you want to reach

as an instrumentalist and as a singer. You direct your sound,

your tone, to a point, and this point is not the microphone, but through

the microphone to the person who is going to listen.

BD: Do you picture the person sitting

in their living room listening to it?

Rootering: Yes.

BD: When you’re performing for a live

audience, are you more conscious of them in a concert than you are

in an opera?

Rootering: Yes. In a concert the

lighting situation is different, so you see them. Some have their

scores, and sometimes you see them yawning sometimes. [Laughs]

BD: Hopefully not very often!

Rootering: No, but I don’t find a person

who yawns is not telling me that it’s boring. It’s just a complete

relaxation, and I find that in a way a positive thing to see.

But still, it is very difficult when you sit on stage and see somebody

right in front of you taking a big yawn. [Both laugh] In that

respect, opera performances are easier because the audience is further

away, with the orchestra pit in between.

BD: Is there more lighting in your eyes?

Rootering: Yes, but I tend not to take

too much into my eyesight. I try not to see the people.

* * *

* *

BD: Let’s talk a little bit about opera.

When you’re on the stage, are you portraying the character, or do

you actually become that character?

Rootering: I do think that I become the character,

but again, it’s a little bit of both. Of course, you’re portraying.

I’ve never been a king in my life, and I probably won’t be one!

I also haven’t been a killer in my life, and I hope I’ll never

be one of those. But I have portrayed both, and you work yourself

into the role so much. As King Philip, for instance, you walk differently

and you act differently. It’s something that gets to you. Sparafucile

in Rigoletto, on the other hand, does things that I wouldn’t do

in my private life! [Laughs] But it certainly is a little

bit of both, and probably more of trying to be the person, and then portraying

it.

BD: You’re on stage for a few hours being

this character. How long does it take you after the final curtain

to throw off the character and get back to being just you?

Rootering: The character goes pretty fast,

but it takes me about an hour or two to get rid of the adrenaline. I

can’t sleep right away. I sleep in the afternoon to be fit for

the performance in the evening. Then after the performance, it’s

just like coming home from work at five o’clock in the afternoon.

You don’t go to bed at six. I usually stay up until two or three.

I’m doing just normal after-work things, like watching TV, listening

to some music, reading the paper.

BD: Do you listen to more opera music,

or do you listen to a different kind of music?

Rootering: I listen to a lot of chamber

music, and a lot of symphonic music. That’s my favorite.

Actually, I hardly ever listen to opera music at home.

BD: You’ve already had too much of it?

Rootering: Well, no. I can’t get

enough, but that’s completely different. As a singer, if you listen

to an opera, you listen to the singers in a different way. You’re

trying to find out how they did that. It’s a professional listening,

whereas I bet colleagues that play in the symphony would say the same.

If they listen to a symphony, they hear this oboe player doing

this and that, and know if it is a Dutch player or a French player. I’m

friends with some of them, but for me a symphony is just enjoying the

beautiful music.

BD: As it was intended?

Rootering: Yes.

BD: Do you hope that the audience who

comes to hear you takes it in as a totality?

Rootering: Definitely, yes. I really

see every single one of us as a little wheel in a huge clockwork, and

only if everything works together is it a wonderful performance.

If it’s not together, it’s not good.

BD: It has to be a cohesion?

Rootering: Yes.

BD: You’re a bass, so your voice dictates

that you sing kings, and murderers, and fathers, and priests.

Rootering: Yes. [Laughs]

BD: Do you ever wish you got the girl?

Rootering: I was very upset! My

father is a tenor [Hendrikus Rootering], and for the longest time

in my life, I thought I was a tenor, too. I knew all his parts,

so I had to learn my bass parts, and I was extremely upset. But

now I’m very, very comfortable with it. [Leaning in and speaking

softly] I do get the girls, but not necessarily on the stage. [More

laughter]

BD: Do you like playing fathers and kings

and priests?

Rootering: It is something that grows on

you. In the beginning, when I started singing, I was pretty

old professionally. I was thirty years old, and to be the wise

father of a forty-five-year-old tenor is a little awkward.

But with the years, you grow into it. You walk slower and talk

slower... [Both laugh]

BD: You’ve done quite a number of Wagner

roles. You mentioned Hans Sachs, which is the biggest Wagner role

for the low voice...

Rootering: I mentioned it, although I haven’t

sung it yet. I’m studying it at the moment, and have the part

ready. I’m going to sing it in a new production in Amsterdam in

1995. This may sound far away from now [1992], and in a way it

is, but in our business it’s just around the corner. The role is

so demanding that I want to have a few years so that the voice has the

chance to grow into it before I do it on stage. [After Amsterdam,

Rootering would do the role in several places, including Chicago in the 1998/99

season, with Nancy Gustafson,

Gösta Winbergh,

René Pape, Eike Wilm Schulte, Michael Schade, John Del Carlo, and

Robynne Redmon,

conducted by Christian

Thielemann.]

BD: As you do Pogner, are you specifically

watching the man singing Hans Sachs to learn a little bit more about

it each time?

Rootering: As Pogner you’re not on stage

all the time with the guy who sings Hans Sachs. I’ve done research

in that respect, but my basic view is different. I’ve been working

with coaches wherever I am, and I get different ideas. I’ve also

worked with a conductor, and from that I get to a point where I want

to start with that role.

BD: Will you now approach Pogner a little

differently knowing what you know about Hans Sachs?

Rootering: No, I don’t think so.

But I have sung all the other Wagner parts that are suitable for my

voice. It’s not that I’m not running around with a piece of paper

saying that I need this role to make it complete. This last role

has been a wish, a dream, and I wanted to wait for a good opportunity

to do it for the first time. It needs to be some place where it’s

big enough to have the seriousness of a big house, but not in a house

where you don’t have the rehearsal time to get the chance to do the role

for the first time, and really have everything settled in six weeks of

work before you go on stage. Then I will sing a run of ten performances

in Amsterdam, which gives a good solid foundation from then on to continue.

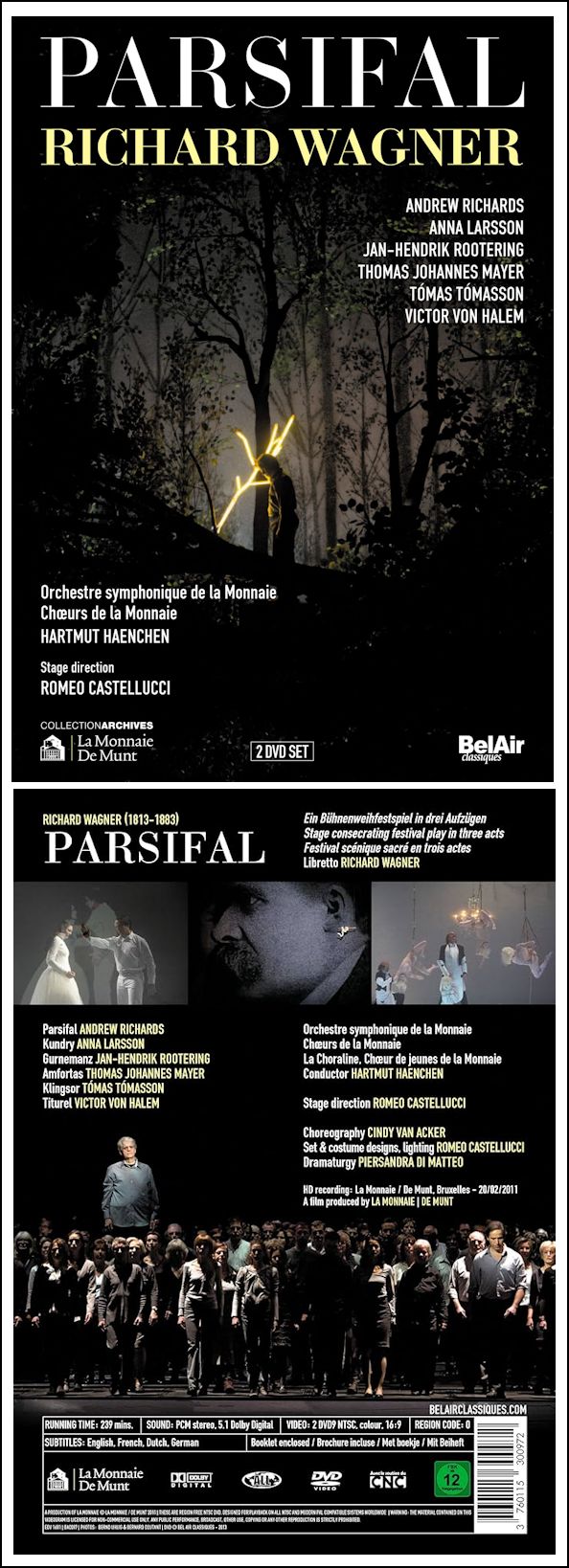

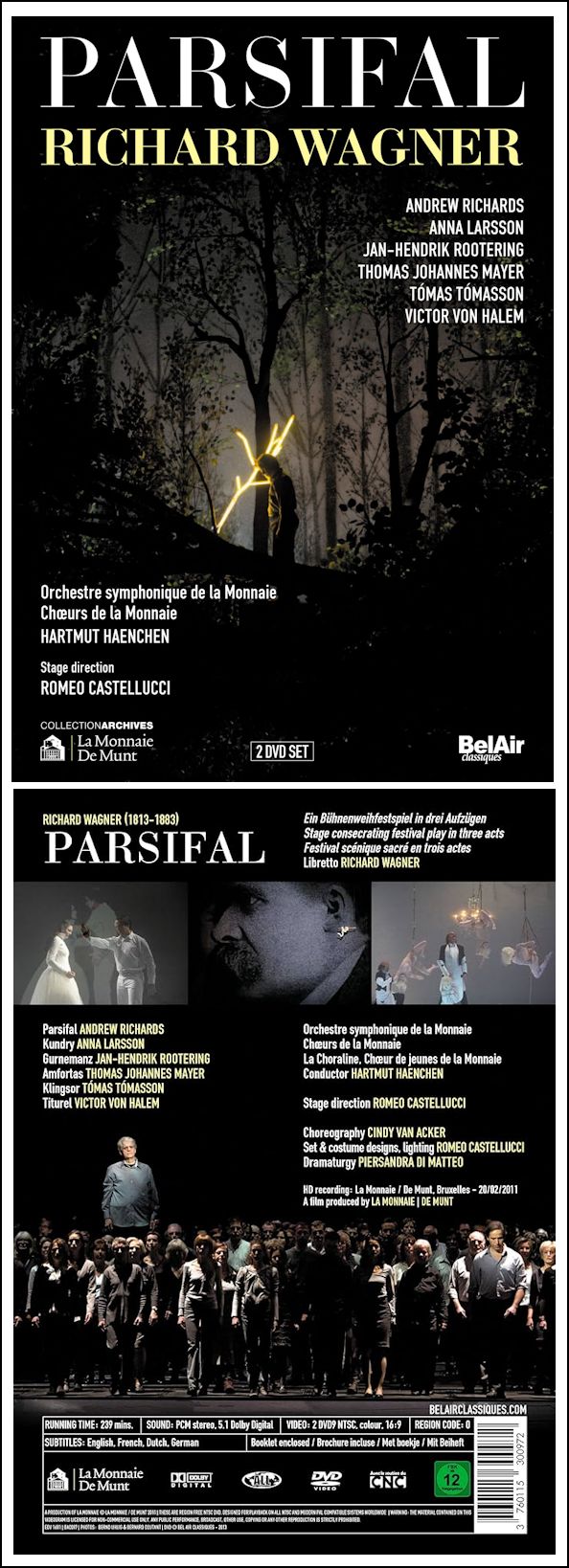

It happened the same way with the role of Gurnemanz in Parsifal,

which I also debuted in Amsterdam, and then sang in Hannover, and Munich,

and then at the Met. Now I can say this is my role, and I’m at

home with it.

BD: Did Wagner know how to write well

for the voice, and particularly for the bass voice?

Rootering: I think so. I probably shouldn’t

say it, but there is a conception that Wagner has only written music

that you have to scream. I don’t believe that. It is beautiful,

lyrical music, and if it’s sung in a positive Italian approach with

lots of legato, it’s wonderful. It can be done that way, and there

are examples of singers who do just that. The difficulty in Wagner’s

music is that he wrote the voice as an instrument into the orchestral

harmony, so it’s harder to do that than to have a carpet orchestra

where you sing the top line.

BD: [With a wink] You don’t want

to be just another trombone?

Rootering: [Smiles] We’re all part

of something big, and if you see that, it works well. In some pieces

the triangle has to do one little thing, but if it’s not there, it’s

not there.

BD: It makes the whole performance?

Rootering: Exactly.

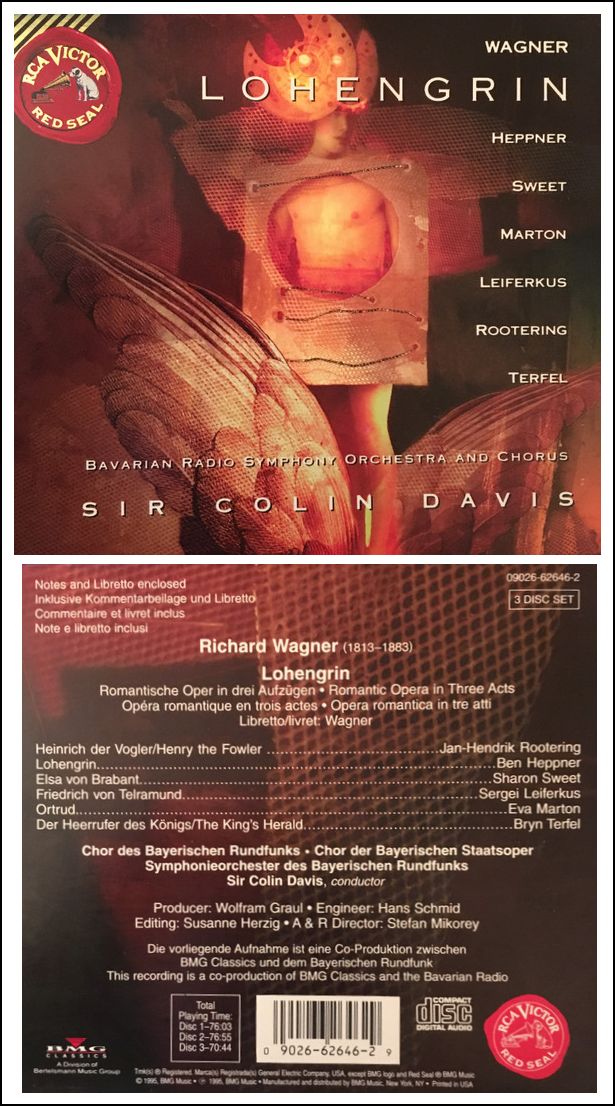

BD: Have you sung at Bayreuth?

Rootering: I haven’t, no. There

were two requests, but it didn’t work out time-wise, which I find very

sad. I’m very sorry about that. I think it’ll come pretty

soon.

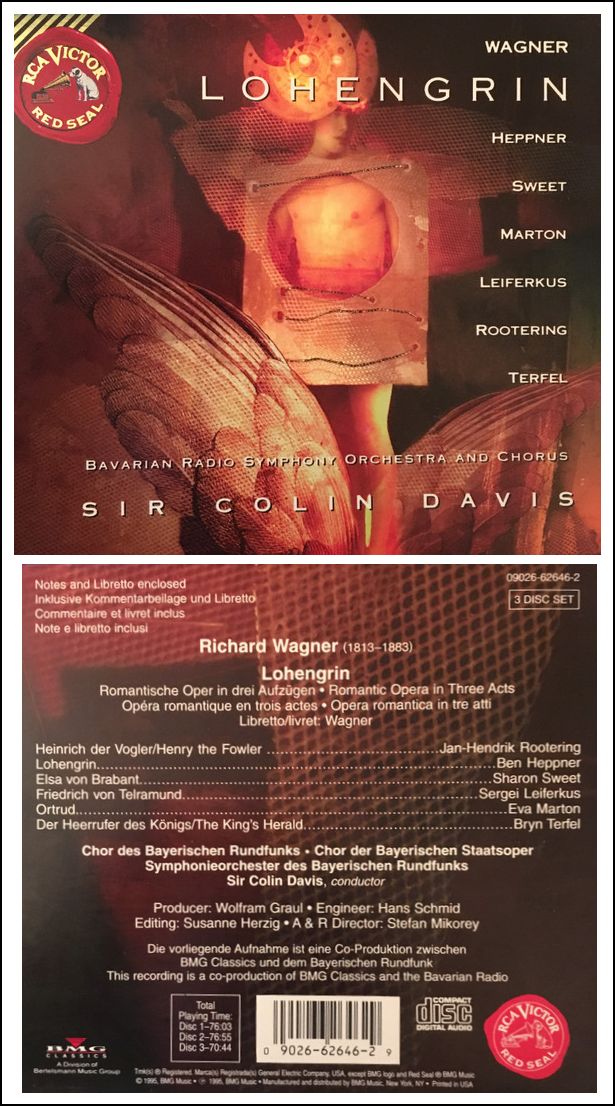

BD: When you sing Wagner in standard houses

with the great big orchestra, without naming names, are the conductors

able to keep the orchestra down enough so that you can soar over the

sound and not be swallowed up?

Rootering: Thinking of Bayreuth, it has

a unique way of building the orchestra. I don’t like the word

‘pit’, but that is what we call it. There, the heavy brass is way

down so they can really play fortissimo, and it comes out as a fortissimo

but not overpoweringly loud. In every other pit in the world, you

have this huge wall of sound in front of you. It is difficult even

if a person is standing in front of the orchestra. When they play

a pianissimo, it would be too loud because of the broadness of the harmonic

complexity of sound. It’s unfortunate that sometimes you’re on

the stage twenty yards back from the orchestra, which itself is a few

yards across. So you’re that distance to the first person who will

listen to you.

BD: Then occasionally you might also have

a scrim in front of you.

Rootering: Right, which also takes away

a little brightness. But basically I don’t mind it. It’s

something you hardly see when you’re on the stage.

BD: Even with the lights shining through

it?

Rootering: Sometimes I’ve worked on stages

where only after the second performance I noticed that there was a scrim.

BD: Some singers have said that they can’t

see even the conductor.

Rootering: With certain lighting, definitely.

But if it’s lit in a good way, you don’t even notice it.

* * *

* *

BD: Let’s talk about some of the individual

Wagner parts. You’ve sung Pogner in Die Meistersinger.

Have you sung any other roles in Meistersinger?

Rootering: No.

BD: Every once in a while, someone will

start out as the Nightwatchman...

Rootering: [Correcting himself] Oh,

I’m sorry, yes, I have sung the Nightwatchman. I sang my first

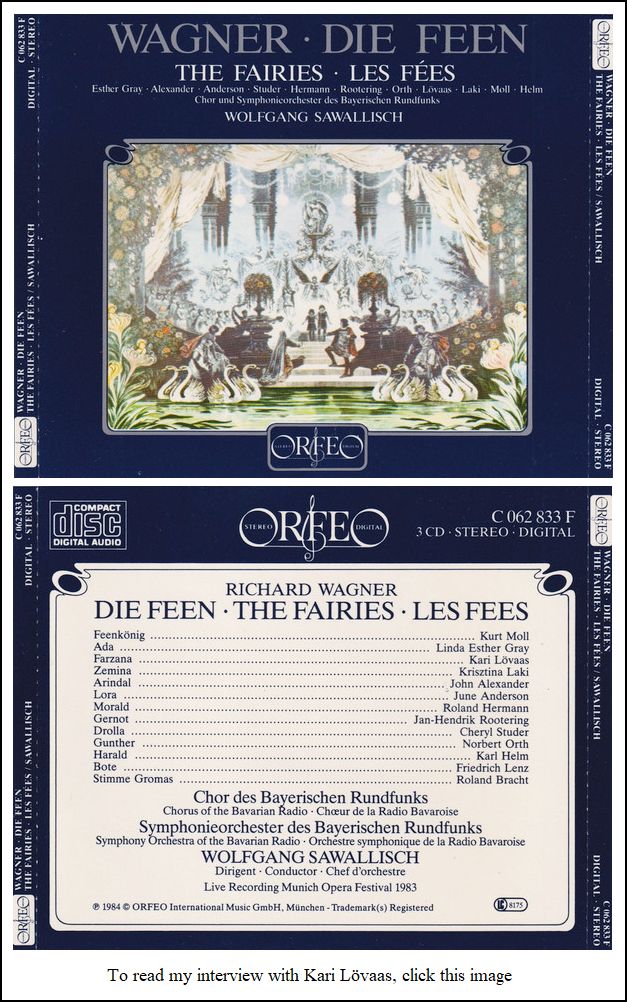

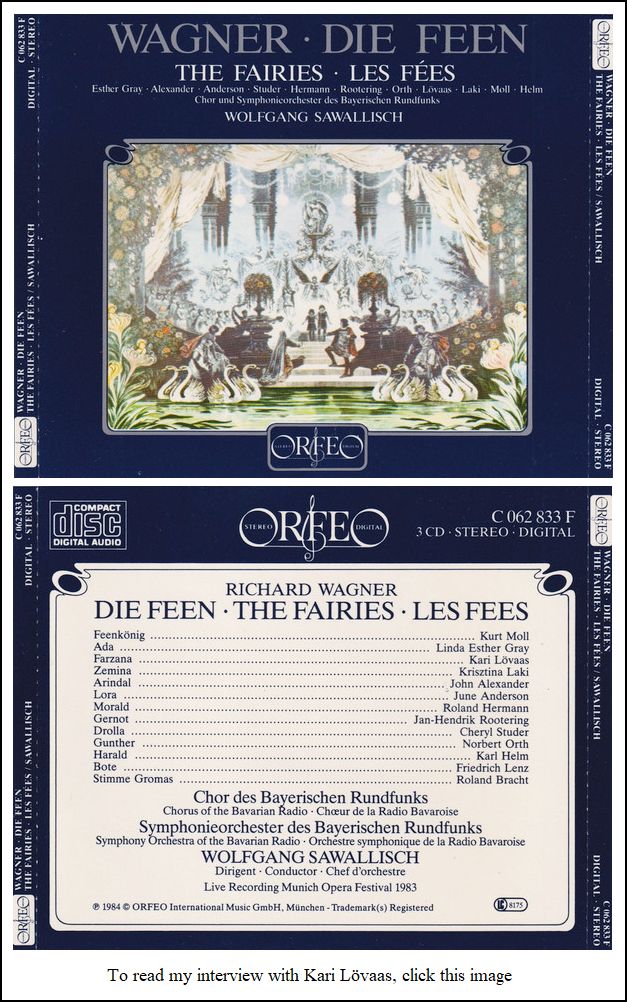

Pogner at La Scala in Milan with Wolfgang Sawallisch,

and then we went with the Munich opera to Tokyo, and there we had

two Pogners, Kurt Moll

and myself. There were two performances in Tokyo, and Mr. Sawallisch

asked Kurt Moll and me if we would agree that, on the evening where we

were not singing Pogner, we would sing the Nightwatchman. So there

was one performance where Kurt Moll was Pogner and I was the Nightwatchman,

and the next performance I was Pogner and he was the Nightwatchman.

BD: Then, of course, you could both cover the

other in case of illness...

Rootering: Yes, that was the reason, plus

he wanted those two performances to have everything really super in

the cast. That was his explanation.

BD: It is very luxurious to have a major

singer in what is a smaller role. [Vis-à-vis the recording

shown at left, also see my interview with June Anderson.]

Rootering: Yes, and we had a ball.

It was wonderful. That was my role debut as the Nightwatchman.

I’d never done that before.

BD: Was it terribly difficult?

Rootering: It’s got to be sung well, and

it sticks out terribly. No, it’s not terribly

difficult, but it was nerve-wracking. [Both laugh]

BD: It’s one of the few places in the

whole opera where it’s almost silent.

Rootering: Exactly, and then it’s either

good or bad! [Both laugh] There is no chance to make up for

an error.

BD: You didn’t play your own horn, did

you?

Rootering: No, no, thank God! [Laughs]

It would have sounded [makes a crude noise]. [More laughter]

BD: You should take a few lessons, and

learn from a horn player. I can understand Siegfried not playing

his own horn, but the Nightwatchman just has the one note.

Rootering: [Continues laughing] Well,

I was very nervous, I tell you.

BD: More so than for the whole role of

Pogner???

Rootering: Yes!

BD: That should give encouragement to

others who are singing the Nightwatchman. If they’re nervous,

they would know that you also were.

Rootering: It belongs with the artistry.

I wouldn’t want to lose being nervous or being excited.

I think it’s a positive thing.

BD: [With a wink] Then you should sing

the Nightwatchman once a year for the rest of your life! [Both

laugh] If you were alternating casts, would you would accept

this again?

Rootering: No, not really. This

was a special occasion, just like at the Metropolitan Opera where I

was asked the day before the Parsifal broadcast to jump in as

Titurel. Because of sickness of a colleague I agreed to do that.

It was for video and for radio. I’d never sung the part in my life.

BD: Did you have any rehearsal?

Rootering: As Gurnemanz you hear it all the

time, but James Levine and I walked on the stage before the broadcast,

and I sang it. It went well. It’s a very short role, and

you think it’s easy, and that you can do that any time. Yes, it’s

easy, but it’s also something where you know there are a few people listening!

[More laughter]

* * *

* *

BD: Let’s come back to Pogner. He seems

to be a rather nice man. He’s willing not to force Eva into an

unhappy marriage.

Rootering: Yes, he’s rather nice, but

still concerned about how he comes across in his community as the

richest of all the Masters.

BD: Is he conscious of that?

Rootering: I think so because in his speech

in the first act he even says that. He talks about it, not in

a bad negative way, but he knows what he is.

BD: He’s very self-confident?

Rootering: Yes.

BD: Is he overbearing?

Rootering: No!

BD: Is it particularly gratifying to know that

you’re going to sail up and have this nice high F?

Rootering: Oh, I like it! [Both laugh]

I know exactly that it’s coming, and it’s fun! [More laughter]

BD: Would he have been happy if Sachs

had won the Song Contest?

Rootering: [Thinks a moment] That’s

a good question. I think so. If you think about the time,

people were concerned to bring their kids into a marriage where they

have safety. They’re looking to be settled, and Sachs definitely

is a settled person. He is loved by everybody, so Pogner wouldn’t

mind too much.

BD: Would he have been upset if Beckmesser

won the contest?

Rootering: Beckmesser is not really somebody

who comes over that well in that community, so that would be the one

person where Pogner would probably not have been pleased.

BD: But he’s qualified to win the contest, so

it’s a possibility.

Rootering: Not only from Pogner’s point

of view, but also from the point of view of life in general in those

days, he would have accepted it. In those earlier days, kids

weren’t even born and they already knew who was going to marry whom sometimes.

BD: Pogner’s wife is gone. Does

he ever remarry?

Rootering: There are a lot of theories

and thoughts about him and the other woman in the piece.

BD: Magdalena?

Rootering: Yes. There are thoughts

about that. I don’t share them, but the thoughts are there.

BD: I would think that all the women of

the town would be clamoring for Pogner.

Rootering: Yes, but then again Nuremberg

is a small city where you have to be careful with your reputation.

That is a big point.

BD: I wish you lots of luck with Hans Sachs.

It seems to be a trend these days that the man who sings

Hans Sachs will be the same bass-singer as Hagen and Pogner, rather than

a baritone who does Wotan and the Dutchman.

Rootering: Yes. In my conception, Hans

Sachs is a bass role. It has the warm richness of a bass voice.

There are a lot of examples in the past, and I just like that sound

better. This doesn’t say that a dark baritone should not sing it.

It sounds just as good, but you need a certain quality.

I can think of a lot of voices I wouldn’t like to hear, because then you

get another sense in the part. He’s a simple, loving down-to-earth

person. He’s warm hearted, and there’s something in a bass voice

that has that. If you have a basso cantante, that’s the right

voice-type, and I like to hear that quality.

* * *

* *

BD: The other long part in your repertoire is

Gurnemanz. Is that role too long?

Rootering: No! [Both laugh]

It is very long, and what I found the most difficult of that role is

remembering all the words. Sometimes the sentences are so long

that you don’t know which tense you started in, present or past. Especially

with a person like myself, who is used to speaking German, it could

go either way, and you come to a point where you wonder what it was I

was talking about. [Both laugh] But, no, it’s not too long.

BD: Do you use a prompter?

Rootering: I sang the role for the first

time in Amsterdam without a prompter. It is something where you

really have to have your mind together. In New York and in Munich

there was a prompter, and it helps. It takes a lot of nerves away.

BD: Can you then concentrate a little

more on the music?

Rootering: The music is so complex that

you have to concentrate on it anyway. In the first act, during

the long speech where he talks to the Knappen (Squires), you can

have a blank in that moment, and then you’re just gone. From

that point of view, it’s really good to have a prompter just to reassure

that you were right with what you just said. You have to know

it anyway. You have to know the part. You can’t rely on

a prompter without knowing the part. That’s logical, but just

tiny little things are where a prompter can really help a lot... when

it’s good! I’ve also worked with bad prompters and they

should better stay home! [Much laughter]

BD: Have you been involved in any staging

where you put your foot on the prompter’s box?

I was thinking of Papageno, who sits on it, but that’s not your role.

Rootering: No, but I’ve done Leporello

in Munich, and in two scenes it’s constantly around there. [Both

laugh]

BD: Coming back to Gurnemanz, how Holy a man

is he?

Rootering: I don’t know. He’s a true believer

of the Holy Grail, and he is a knight, and a servant of Titurel. He

keeps the whole thing together until they find the new leader.

He is, I believe, a kind of head of the family for this opera. He’s

not a person who would wag a finger at somebody else, and he’s not a person

who is dictating something. I believe he’s a person who is telling

something, and if you follow it closely, you’ll see that he starts and

stops a few times, telling them they shouldn’t ask that. He catches

himself talking about something he didn’t actually want to talk about,

but then he starts again and gets carried away in talking about it. It’s

a spinning mind, and the others are just accidentally overhearing in his

thoughts.

BD: Does he like having that role

thrust upon him?

Rootering: I don’t know whether he likes

it or not, but it’s something I don’t think he thinks about. He

thinks this is what he has to do. He has to keep on. He has

to teach, but in a way to let them see how he lives, and then they can

do it or not.

BD: He will teach by example?

Rootering: Yes, right.

BD: Is it a grateful role to sing?

Rootering: I love it. I love every

second of it. It’s really beautiful.

BD: What do you do during the second act

[where his character does not appear]?

Rootering: It depends! [Both laugh] I’m

usually laying on a couch...

BD: Do you let the voice cool down and

re-warm it, or do you keep it idling the whole time?

Rootering: No, I let it cool down, and

warm up again.

BD: Is Parsifal an opera, or is it a sacred

work?

Rootering: What is sacred? To me it’s a

piece of music which is wonderful in its own point, not to be compared

with anything else. But then the others aren’t to be compared

either. It has a point of its own, and it should be seen like

that. I don’t think you should make it too Holy.

BD: Should there be applause after Act

One?

Rootering: If the people like it, why

not? That’s something I’ve never been able to understand.

I know where that custom comes from, and I understand the idea, but

applause is where people are relieved. After that time they’ve

been sitting there stunned or not able to do anything, and the applause

helps the people to off-load their energy, let alone their excitement

that they’ve just seen something beautiful. It shows their emotions

that they have been saving for about two hours. If they want to

be Holy, don’t go to the bar to grab a drink!

* * *

* *

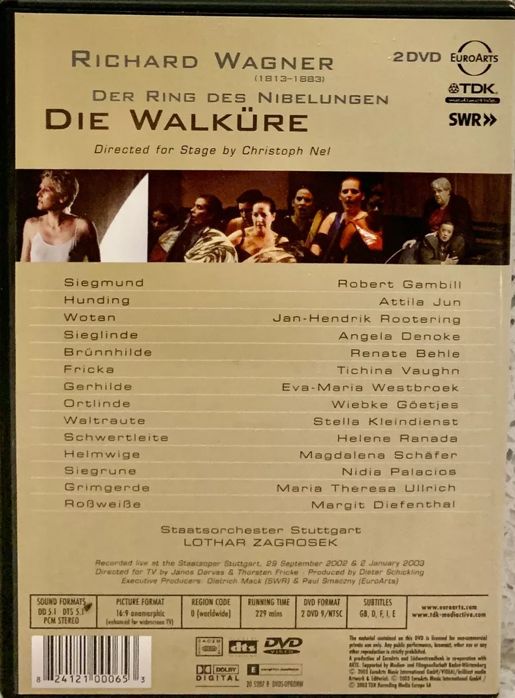

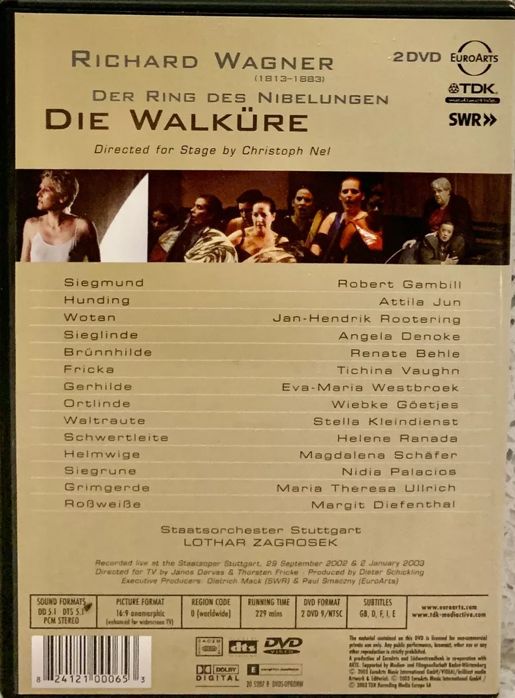

BD: Let’s move to the Ring. What

are the parts you sing?

Rootering: Fasolt. I’ve also done

Fafner and Hunding.

BD: No Hagen?

Rootering: I haven’t done that yet, and

quite frankly I don’t have an offer to sing it. Otherwise, I

would. Sometimes offers come and sometimes not. You never know.

That is a question of taste. Some conductors, some heads of

opera houses, some stage directors like the Hagen to have a hard, loud

sound, which I do not. I have a kind of mellow voice, and I’ve heard

Hagen that way, and I personally like it. But then again, I don’t

think that because Lady Macbeth has an ugly personality, she has to sound

ugly. I say this without pointing at anyone in particular. This

is plainly how you want to see it.

BD: You would be a little more sinister

and more subtle as the Hagen, rather than more brutal?

Rootering: Yes. I see him as much more friendly.

Siegfried is not particularly stupid, so if Hagen is such a brute,

Siegfried would sense something and run away. You have to be extremely

friendly to get this person as a friend, and then you can do everything

behind his back. That’s how I look at it.

BD: In Rheingold, how do you

decide which giant you will sing, or is it just whichever is offered?

Rootering: No, again it’s a question of

voice. Fasolt is the more lyrical, more basso cantante,

and Fafner is a basso profundo. This is also a question

of taste. I ended up mostly singing the Fasolt, but I have sung Fafner

on stage a few times, and I’ve also recorded it.

BD: Have you done the Fafner in Siegfried?

Rootering: Yes.

BD: Is that at all grateful, or is that

just something to sing through and get it over with?

Rootering: Again, I always insist on

coming back to this, of where there is a question of what is grateful

and what is not grateful. If we all only want to do what is grateful,

then there’s no opera. A small part is something you can do beautifully,

and where you have a distinct important point. I have worked in

houses where the main soloists are top-of-the-line, and then you have

— pardon my expression

— some crap doing

the small parts. That drags down the whole thing. The

better the small parts are, the higher the whole production is. If

the person who is singing a small part has a wonderful voice, you sit

in the audience and appreciate him or her. It’s better if the people

want to hear more of him or her, instead of going [gives a big sigh]. The

question is what is more rewarding for yourself. I know what you’re

getting at, and I certainly prefer singing Gurnemanz than Titurel.

But I’m not putting Titurel down in any way. It’s a very, very

important part, and has to be sung beautifully.

BD: It’s very encouraging

that you’re such a team player. You won’t let the team down

if you are singing Gurnemanz or if you’re singing Titurel.

Rootering: Yes. I grew up like this.

I learned it from my father. I’ve seen operas since I was two.

I didn’t particularly like them then, but that’s something else!

[Laughs] The chain is as strong as the weakest link.

BD: For me, the best operas are ones which

are cast from strength top to bottom.

Rootering: Exactly, and then you have

those moments where you have goosebumps, and you feel chilled to the

bone. That’s wonderful.

BD: One last Ring role, Hunding.

Is he evil, or just put in a bad situation?

Rootering: He’s a strong, honest believer.

He believes what he does is the right thing, and he does that until

he dies. He believes he’s absolutely right.

BD: Would he have been better off if he had been

paired with just an ordinary woman, rather than with a Völsung?

Rootering: In terms of the outcome of

the story, probably yes. But he’s a hunter.

BD: Is he happy in his marriage?

Rootering: I don’t think so, but I don’t

know. One has to constantly consider the facts that we were talking

about earlier. The writing and the story have taken place a long

time before. He comes home, and tells his wife to have food and

drink on the table, and if that’s there, I think he’s happy.

BD: He doesn’t look beyond that for happiness?

Rootering: I don’t think so.

BD: [With a wink] He’s not a philosophical

kind of guy?

Rootering: No, I don’t get that impression.

[Both roar laughing]

BD: Is there anything that you can or

should do to project these characters from long ago to audiences

that are living in the 1990s?

Rootering: I have been part of a lot of tryouts

where things were moved into our times. The most famous one is

this area is certainly the Tannhäuser here in Chicago. I

don’t want to get into that much deeper, but what does it do?

Wagner did not write about Jimmy Swaggart, and I personally don’t think

Jimmy Swaggart is that important that we should do an opera about him.

But fine, if it’s done and I’m hired to do something, I can choose

to leave. But I didn’t, because the person who did the staging

[Peter Sellars] is

an intelligent man who had certain ideas, which I didn’t necessarily agree

with. [The cast included Nadine Secunde, Richard

Cassilly, Marilyn Zschau/Sharon Graham, Håkan

Hagegård, Ben Heppner (Walther), conducted by Ferdinand Leitner.]

BD: But you projected these ideas as best

you could?

Rootering: Yes. That’s my job, and

that’s what I’m doing.

BD: If you were offered that production

again...

Rootering: No, because I don’t see the

point where an audience leaves the house saying it was fun. It’s

not necessarily fun in terms of being an entertaining evening. It’s

beautiful music, but the story is not funny, and it has nothing to

do with any kind of respect for Wagner. I cannot find the combination

of the Wartburg and the Crystal Cathedral.

BD: Where should be the balance then between

the artistic achievement and the entertainment value?

Rootering: Of course it’s entertainment, but take

for example the Aïda which was placed in a high-rise, and

Aïda is a cleaning woman. How far do you want to go, and how

stupid do you think the audience is? This is something I really think

a lot about. Audiences nowadays are so well-trained and prepared,

that a stage director who does that takes twenty facets away which

that piece has, and shows just one or two. It’s a lot better if

you allow the audience to think. If you follow just the words of

Wagner’s Ring cycle, you’ll find out it’s nothing but today’s

corporate business.

BD: But you don’t need to put them in

business suits?

Rootering: Not necessarily, because you can figure

that out if you read the words. It has been done in a brilliant

way by Patrice Chéreau in Bayreuth, which was such a remarkable

production. But he did not change the story to an extent where

you don’t see the story anymore.

BD: For Tannhäuser Sellars

changed the story?

Rootering: I think so.

BD: Do you mind if a director shakes

the audience up?

Rootering: Oh no, on the contrary! Speaking

about this Tannhäuser, the most beautiful thing was the third

act, where the Pilgrims came back from Rome on a very well-known American

airline, which is okay. Why not? It did not change anything.

There were a bunch of people who went to Rome for a certain reason,

and then they came back, and one was missing. There was a woman

who was sitting at the airport waiting for them, and her beloved wasn’t

there. That’s what the story is.

BD: I thought it was a good touch that

the security people came and dragged him out of the plane.

Rootering: I loved that! It was great. There

I say, yes, mission accomplished. Although it is completely

modernized, and has nothing to do with his feet hurting because he didn’t

walk on the easy road, but still, that is something which is a big

capital YES! The second act, no, and the first act, no!

BD: Maybe he should keep the third act

and rework one and two? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown

at right, see my interviews with Eva Marton.]

Rootering: That would be a good idea,

but I had lots of fun. It was probably one of the most enchanting

times I had. Lyric Opera is a marvelous place to work, and I’m

happy to be coming back in 1994. I’m a thinking person, and if you’re

not allowed to think and reflect on these things, then I don’t want to

do it. Then you’re a puppet on a string, and I don’t want to be

that.

BD: What is the role you’ll be singing

in 1994 [two years hence]?

Rootering: This is a new production of

Capriccio, and I’ll do La Roche. I’m really looking forward

to it. [The cast would include Felicity Lott, Kurt Streit, Gerald Finley,

Rodney Gilfrey, Cynthia

Lawrence, Bonaventura Bottone. Andrew Davis conducted the

John Cox production.]

BD: Do you like having the supertitles?

Rootering: Yes and no. They are

very helpful because the audience understands a lot more, but they’re

also, at the same time, very distracting because people don’t see

the action any more on stage. They constantly watch the little

screen, and if it’s done like it was in the Tannhäuser production,

it says something different than what was being done on stage, and I don’t

like that.

BD: Don’t people just look to see the

text, and then come back to the stage?

Rootering: Yes, but it really depends

on the translation. I’ve seen it a lot of times where people laugh

at completely different points, and if the translation is bad, then the

people laugh at the punch lines before or after the action, and that is

extremely difficult for us.

* * *

* *

BD: Another of your noble characters is King Marke

in Tristan.

Rootering: Yes. I’ve done that quite

a lot.

BD: How can you keep him from just pontificating?

Rootering: It’s just a feeling of a human being

who is hurt by whatever reason. His friend, who has offered himself

to do that favor, has betrayed him in the ugliest possible way. Yet,

at the end he says he didn’t mean that. He wanted to get them together.

BD: That’s because he finally understands

why it happened?

Rootering: Yes, he knew what had happened.

He says that.

BD: Would you perform any of these operas

in translation?

Rootering: No, purely because it would

be so much work to put them into other words. I don’t see the

necessity. If you feel that singing it in English means the audience

can really understand it, I won’t believe it, because I do speak German,

and I don’t understand all the German that’s being sung in Germany! [Both

laugh]

BD: Do you work harder at your diction

in Germany knowing that some of it can be understood?

Rootering: I personally work hard on my diction,

period! One of the reviews that made me jump high was after Billy

Budd at the Metropolitan Opera. It said that I was among the

ones who were able to be understood, and that’s a very, very good compliment.

But it’s a problem with singers, especially in the high range, to keep

the diction working.

BD: Claggart is a really good role.

Rootering: Yes, and it’s

the role where I’ve suffered the most.

BD: Why?

Rootering: I will never forget it...

After one rehearsal, when Billy kills Claggart accidentally, and is

then sentenced to death, I went home and was crying my eyes out. I

was devastated, really. There’s this beautiful aria Billy sings

when he is down in the hold of the ship. I was finished, but I stayed

to listen. My dear friend, Thomas Allen, who sang

Billy, touched me in a way that I’ve never experience before. I

went home crying. I was just devastated. It was something I

hadn’t thought could hit me that way.

BD: It shows that you can be caught up in the drama

and the music.

Rootering: Right.

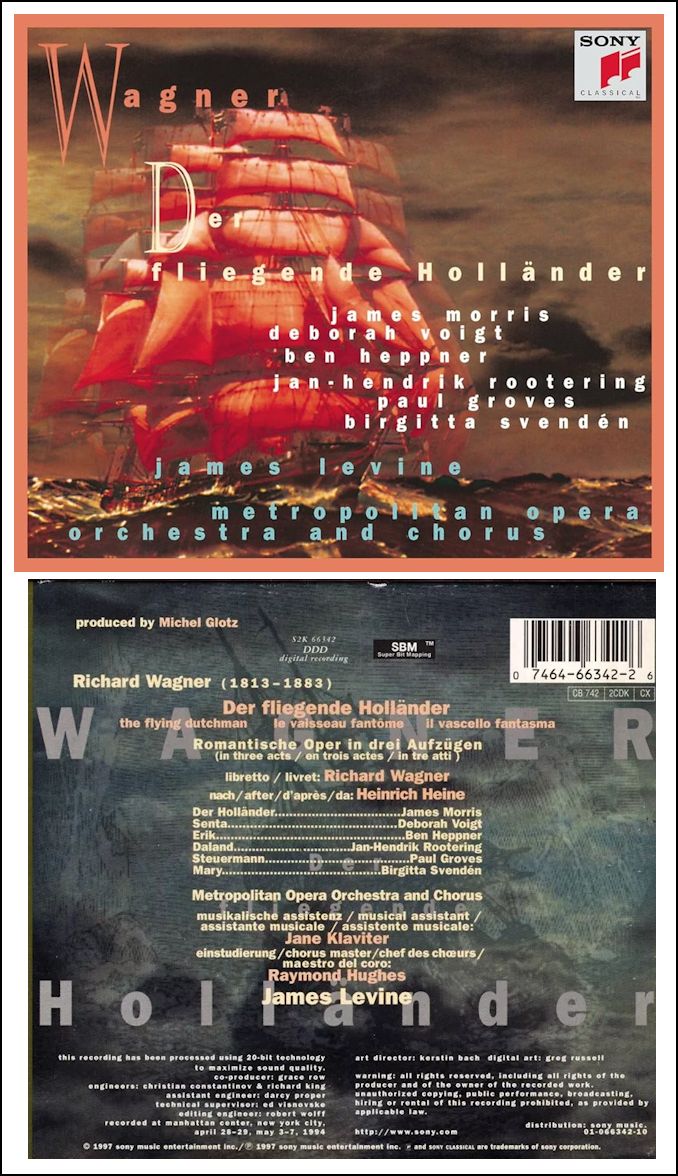

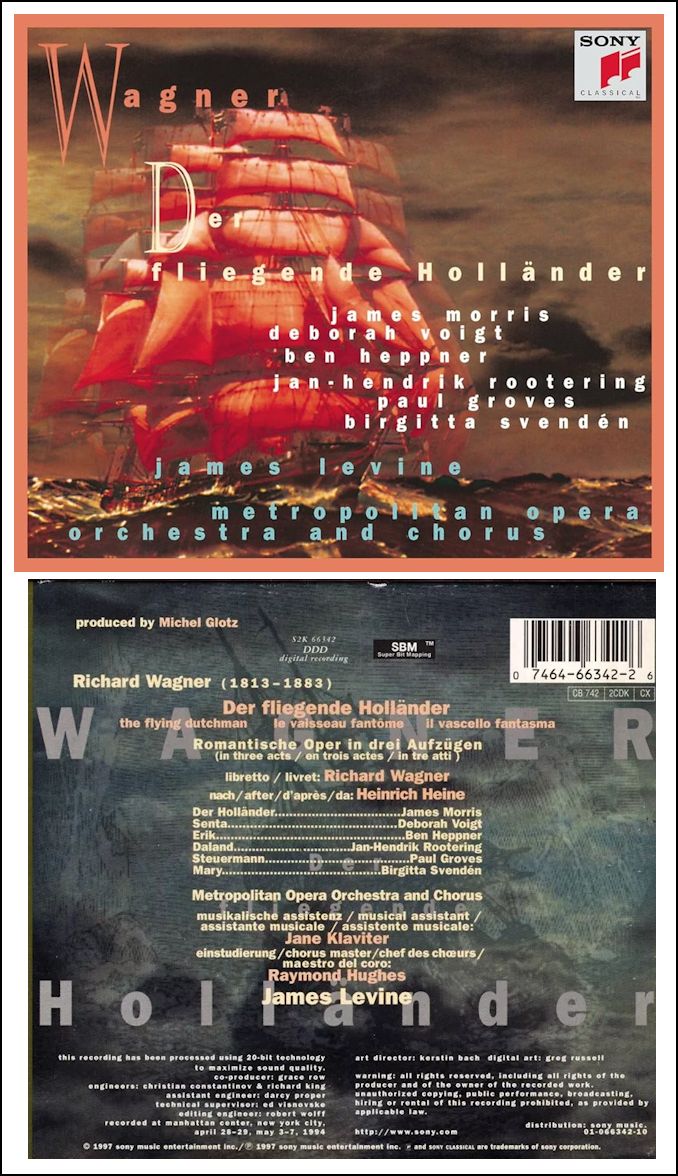

BD: One last Wagner role, Daland.

Rootering: I’ve just done it just recently.

BD: Is he a nice fellow?

Rootering: He’s a sailor, and he can

make money easily.

BD: Is he greedy?

Rootering: Yes, a little bit. The way

he offers his daughter would be disgusting nowadays, but back then,

again in those days, if you read the history books this was just

common.

BD: Then the question becomes, would Daland

knowingly offer his daughter to someone he knew was evil or cursed?

Rootering: No, no, no.

BD: So Daland is not terrible, he’s just

an opportunist? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right,

see my interviews with Deborah

Voigt, Paul Groves,

and Jane Klaviter.]

Rootering: If he would know that this

was the Flying Dutchman, he wouldn’t even be there and talk with him.

Daland would be far too afraid.

BD: And yet the Flying Dutchman is the

one right person for Senta?

Rootering: Yes.

BD: Is Senta nuts?

Rootering: No, she’s caught up in a story, in a

fairy tale, and is possessed with the wish to heal this poor soul.

BD: She succeeds in that wish theoretically.

[Both laugh]

Rootering: Yes, but I don’t think you

can call that nuts. It’s a little hysterical maybe, but it’s

a great opera plot. It has four very different characters, and

it’s very well put together.

BD: Should it be done in one piece or

three?

Rootering: I’m used to doing it in one,

so I can’t judge how it would feel in three. If you hear it

straight through, the story is much more compact, and it flies by.

Something hits you, and you really go out thinking. This

music is so strong, and the story is good, and I like it when it just

goes on without stopping.

* * *

* *

BD: Of the non-Wagner, you sing a lot of Mozart?

Rootering: Yes.

BD: Is there a secret to singing Mozart?

Rootering: No. There’s a secret to singing,

and that’s how we started out. I don’t see Wagner parts as having

to be screamed necessarily. Mozart is the judgment day for

every voice, because you can’t get by with a lot things you could probably

get by in other operas. Mozart shows everything.

BD: Do you like singing Mozart?

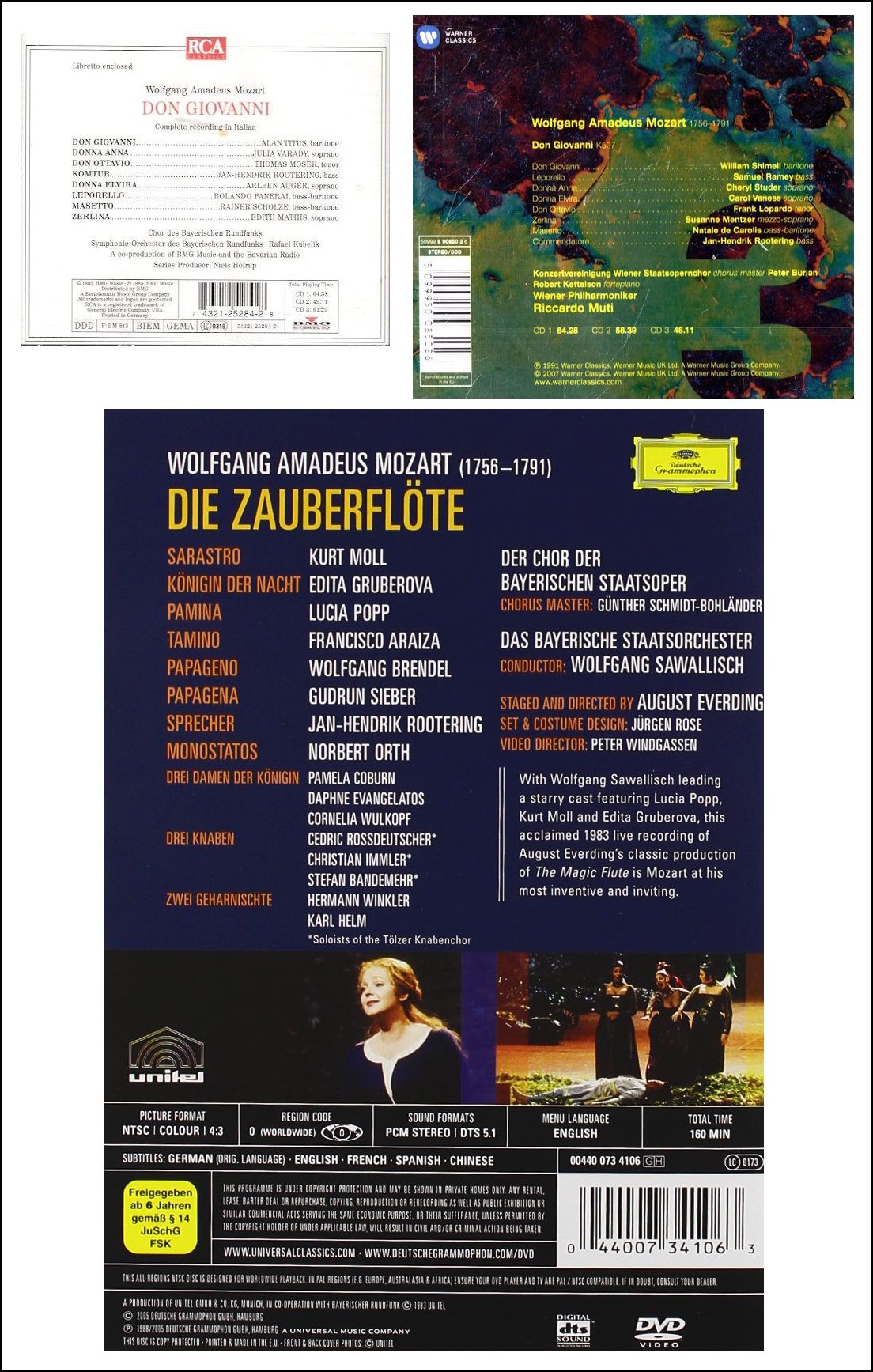

Rootering: Oh yes. I’ve done Leporello,

I’ve done the Commendatore, and I’ve even done Masetto in the beginning

of my career.

BD: Will you do Don Giovanni?

Rootering: Maybe later. I don’t

want to say no. [We then mention the other roles, including

the female parts, and even being the conductor, and have a huge laugh.]

I’ve done Sarastro, of course, and the Speaker in The Magic

Flute, as well as the Second Armed Man. In Così, I

have sung Don Alfonso.

BD: Would you ever do Guglielmo?

Rootering: No.

BD: It’s too high?

Rootering: Right. I’ve

also done Bartolo in The Marriage of Figaro.

BD: What about Osmin?

Rootering: That’s a role I don’t sing.

I’ve never done that.

BD: Why not? [I look down at

a few notes I had made, and saw that this role was listed in one of the

books.]

Rootering: This is wrong information.

[Thinks a moment] It could be because I was scheduled to sing it

at the Munich Opera, and as you know, our contracts run ahead a lot

of time. I had decided a year before it was to happen that I wouldn’t

do it.

BD: Why not?

Rootering: I don’t know. I can’t

give you a logical answer. [Laughs]

BD: You just didn’t feel you should do

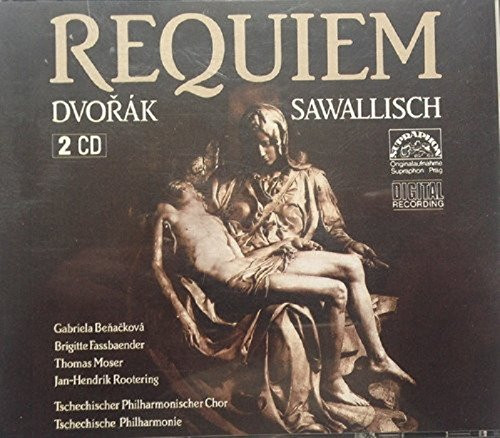

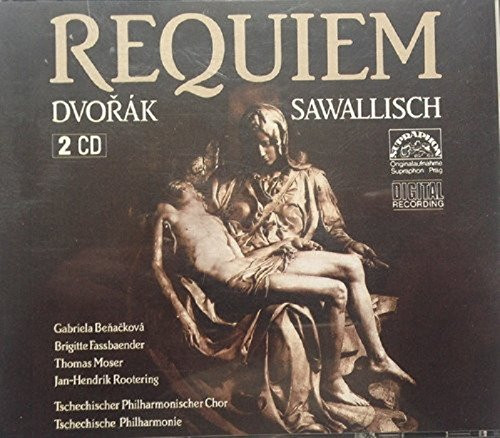

it? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interviews

with Brigitte Fassbaender,

and Thomas Moser.]

Rootering: My teacher is my father, and

he once said that if you have the slightest doubt, don’t do it!

I keep that as my biggest advice, and when I have doubts, and I don’t

do it.

BD: Do you like being booked a long time in

advance?

Rootering: Yes and no. Yes, because

it gives you the time to know what to study when, and also the security

of income, to be very frank, and no, because it takes away the possibility

for nice things that come too late that you would like to do, but you

are already on a contract.

BD: You don’t like to shuffle things around?

Rootering: No, I don’t. Once I’ve

signed a contract, I’ll stick to it.

BD: One other role, Baron Ochs. Tell me

about him.

Rootering: Yes, one of my favorites. He’s

just the sweetest guy. He doesn’t know he’s so obnoxious.

He’s just himself, and he tries to be very elegant and very cordial,

but he makes mistakes left, right, and center. I don’t think he has

anything mean in him. It’s just this is a country bumpkin, and

he smells the big city, and thinks this is the way to do things. But

then again, if you look at the Marschallin, it’s certainly not the first

time and it’s certainly not going to be the last time they get together.

In a way they’re very, very close. It’s just that the Marschallin

has a little more education than Baron Ochs.

BD: Do you purposely try to make Leopold

look like you?

Rootering: So far it’s only happened once

that I had a Leopold who really looked like my son, but most of the

time it’s not that way. [Both laugh]

BD: Do you sing the [optional] low C when

you exit in the first act?

Rootering: Yes, but you really cannot

always count on it, because it is at a moment in the piece where you’ve

worked so much, and you’ve sang a lot of high notes. It’s always

there, but sometimes it’s loud and sometimes it’s not. [Laughs]

* * *

* *

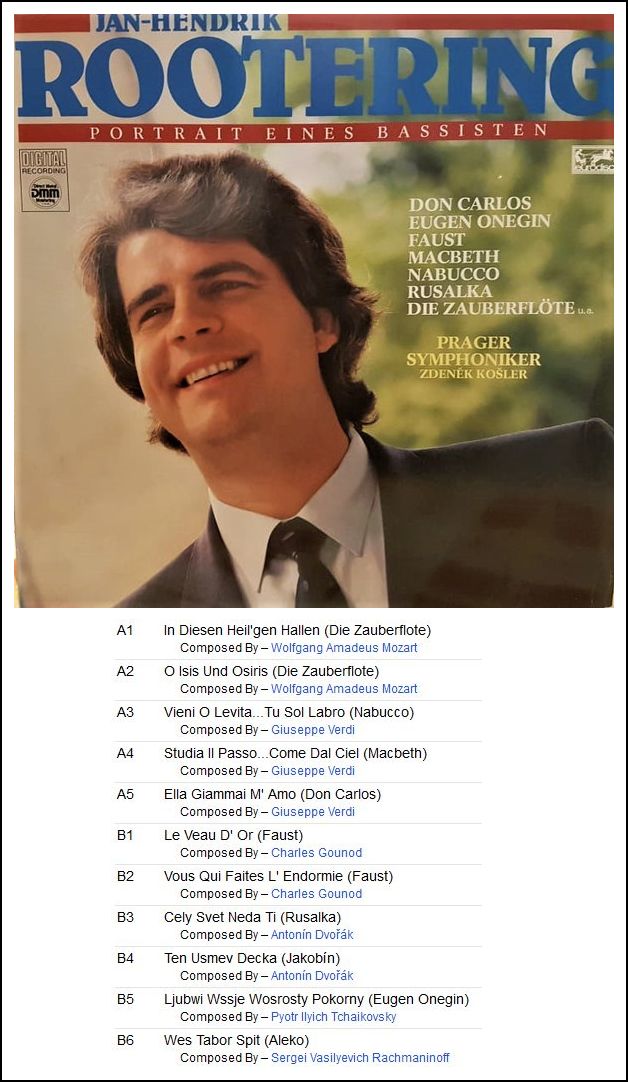

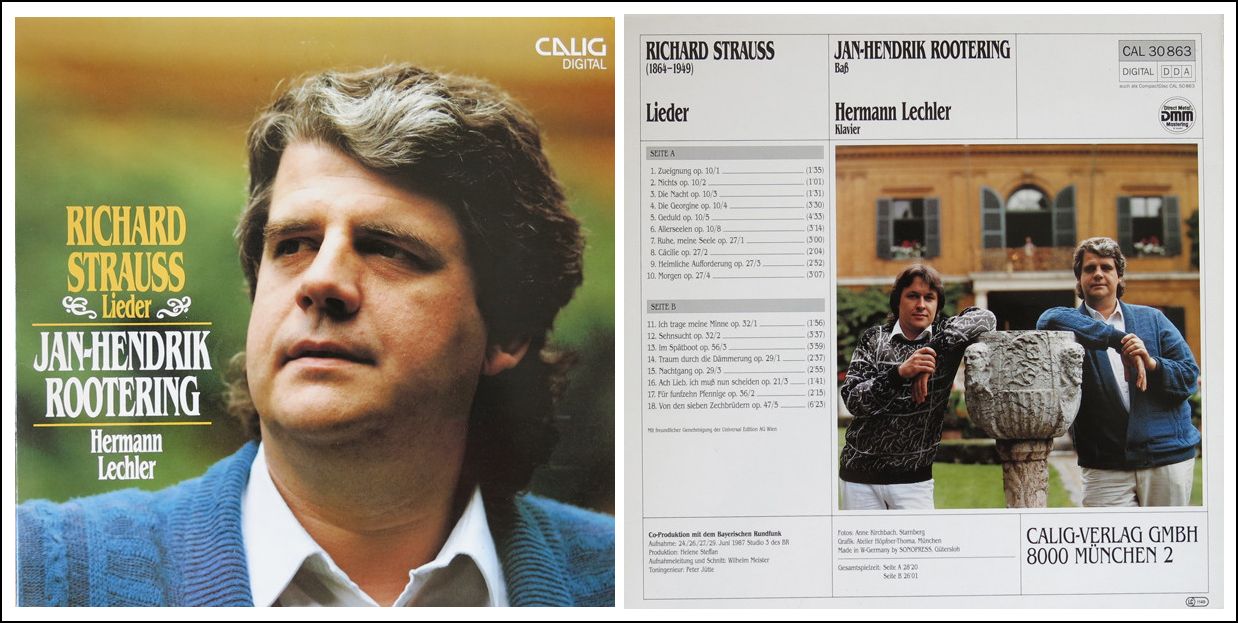

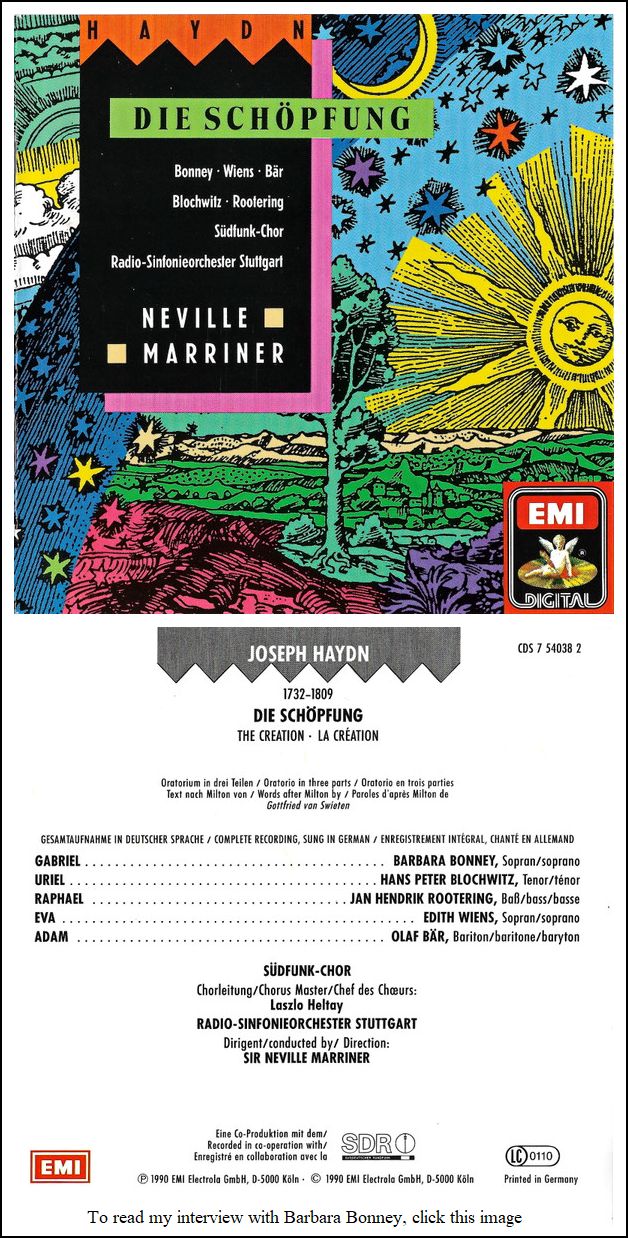

BD: You’ve made some recordings...

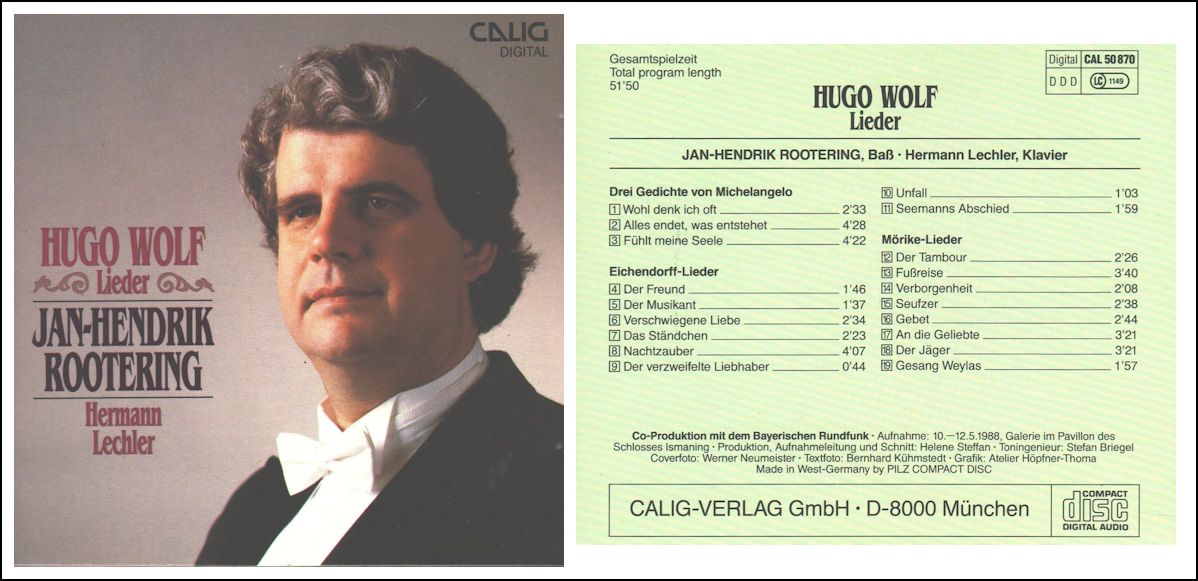

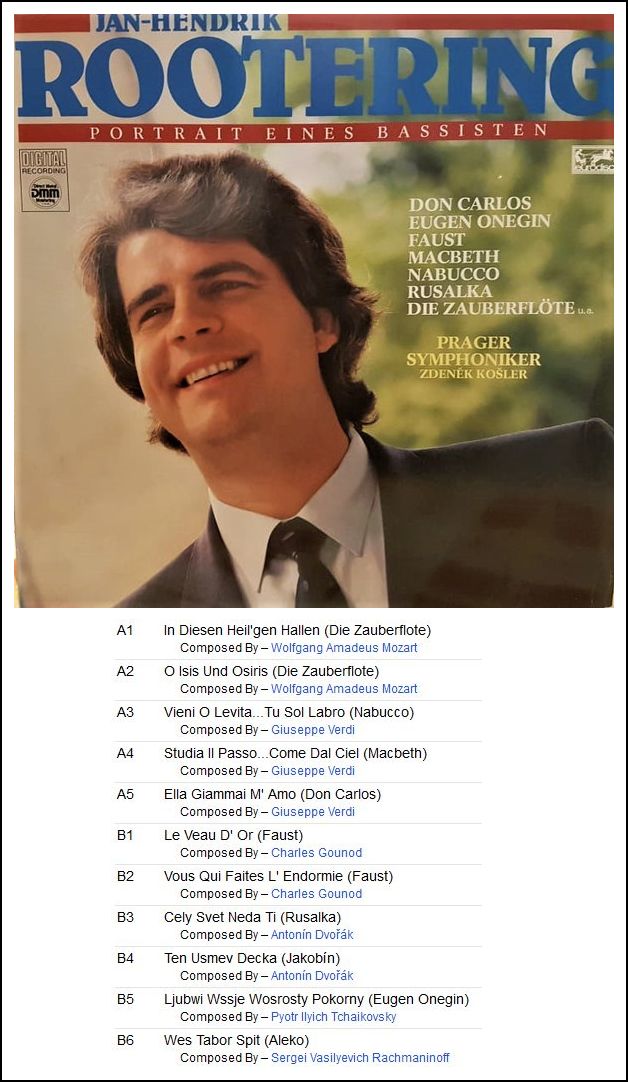

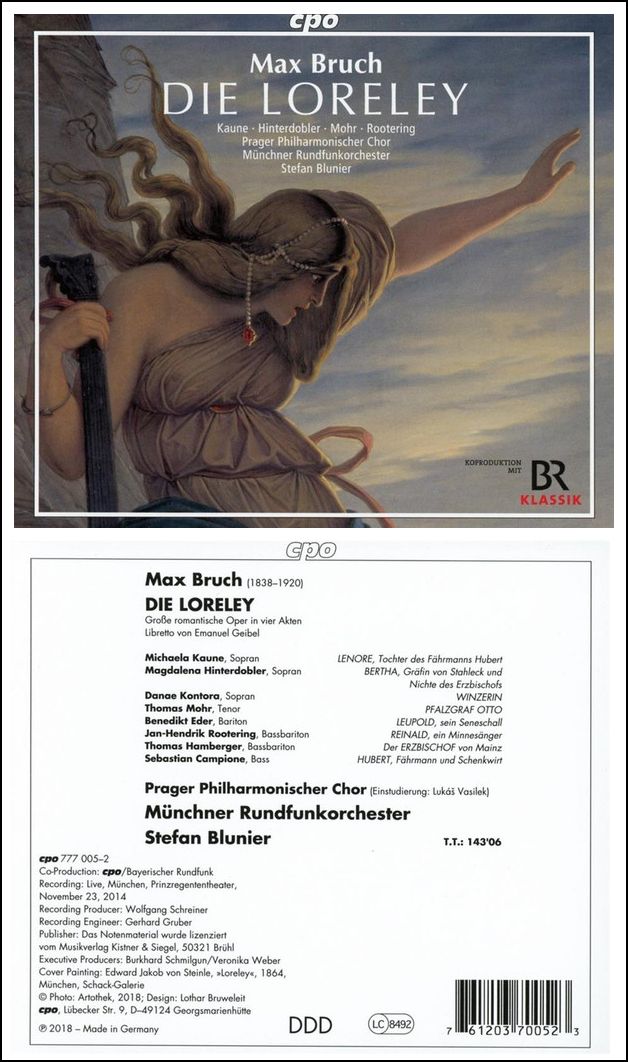

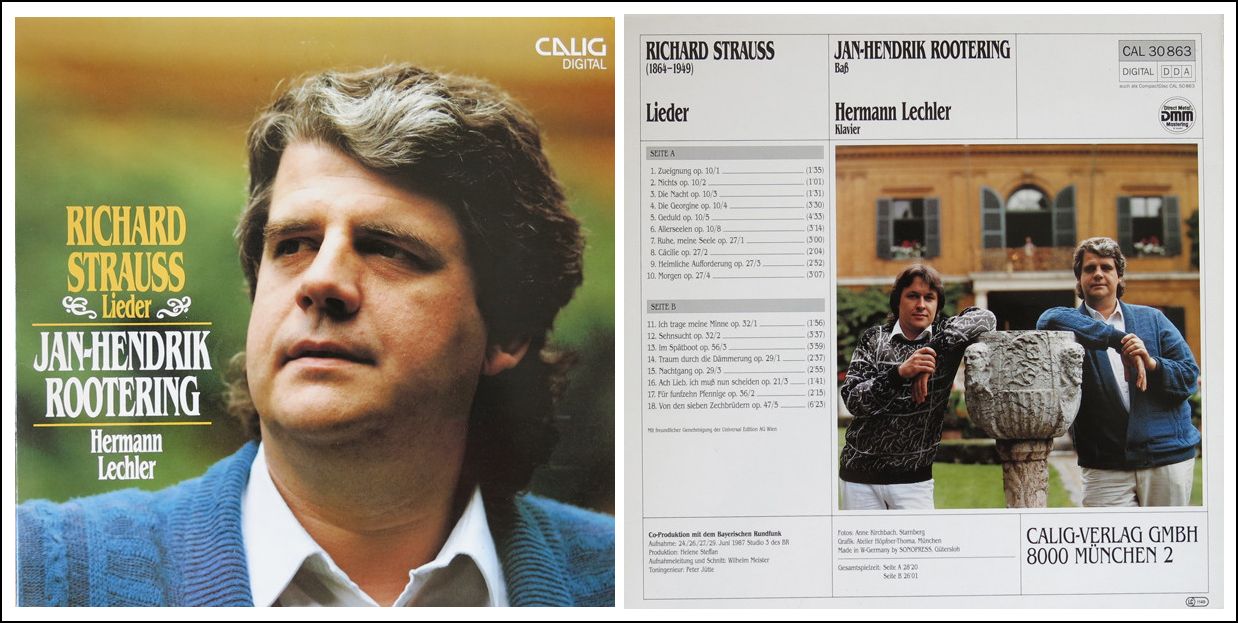

Rootering: I recorded a solo album with

opera arias, and I’m doing Lieder recordings with a small label

in Germany that specializes in chamber music, which I really find

wonderful. I can choose the program and the pianist. This

is a very important point. I have done Liederabends with

Wolfgang Sawallisch, which were fantastic. I would work with him,

or James Levine, or Daniel

Barenboim any time. I don’t know if they’d work with me...

[Laughs] The pianist I work with is a friend. We

have known each other for about fifteen years, and we have always worked

together. For the past six years we have recorded together, and

we have reached the point where working with him is easy. He knows

exactly how and when I breathe, and I know exactly how he hits his keys.

It’s a lot easier to work with him than with people you don’t know

on a day-to-day basis.

BD: It’s comfortable?

Rootering: Right, but not in a way that

he only does what I want. Not at all. We fight about it,

and we discuss it. We work hard, and the outcome is something that

we both can deliver any time. I certainly don’t see the pianist

as the servant of the singer. It’s very much a duo, and if that’s not

there, then it’s boring. Why do it? You could just as well

put on a tape-recorder and sing to that. [Both laugh] It has

to be different every evening. You get up in the morning, and

you’re in a good mood or a bad mood, or this or that happened, and all

of it has to have some kind of influence on your evening’s performance.

BD: Are you pleased with the recordings, because they

will always be the same?

Rootering: Oh, yes! We work until

a point that we feel it is what we can listen to for the rest of our

lives. [Both laugh] I have now Winterreise which

is going to be released soon, and which I’m particularly proud of, if I

may say so. It comes to a point where even the cover photo has

been made by a friend of mine, which is nice. It’s weird, but I

really like that.

BD: Thank you so much for speaking with me today. I’ll

get several uses out of this material, on the radio and in print.

Rootering: Great. Thank you.

© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at the Ravinia Festival in Highland

Park, Illinois on June 18, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB

in 1994, 1995, 1997, and 2000. This transcription

was made in 2024, and posted

on this website at that time.

My thanks to British soprano

Una Barry

for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these

interviews for print, as well as a few

other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie

was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until its final

moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have

also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his

broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited

to visit his website for more

information about his work,

including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of

his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information

about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive

field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.