| [Portions of two brief biographies] George Rochberg (Composer) Born: July 5, 1918 - Paterson, New Jersey, USA Died: May 29, 2005, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, USA The American composer, George Rochberg, attended the Mannes College of Music, where one of his teachers was George Szell. George Rochberg abandoned serialism after 1963 when his son died, saying that serialism was empty of expressive emotion and was inadequate to express his grief and rage. By the seventies he was causing controversy with often obviously tonal music. He compared atonality to abstract art and tonality to concrete art, and compared his artistic evolution with Philip Guston's, saying, "The tension between concreteness and abstraction" is a fundamental issue for both of them. George Rochberg is perhaps best known for his String Quartet No. 6 which includes a movement of variations on the Johann Pachelbel's Canon in D. A few of his works were musical collages of quotations from other composers. Contra Mortem et Tempus, for example, contains passages from Pierre Boulez, Luciano Berio, Edgard Varese and Charles Ives. [Names which are links refer to interviews by BD elsewhere on this website.]

George Rochberg was the chairman of the music department at the University of Pennsylvania until 1968, and continued to teach there until 1983. His later works tend to be neo-romantic (and even neo-Mahlerian) in style. === === ===

=== === === ===

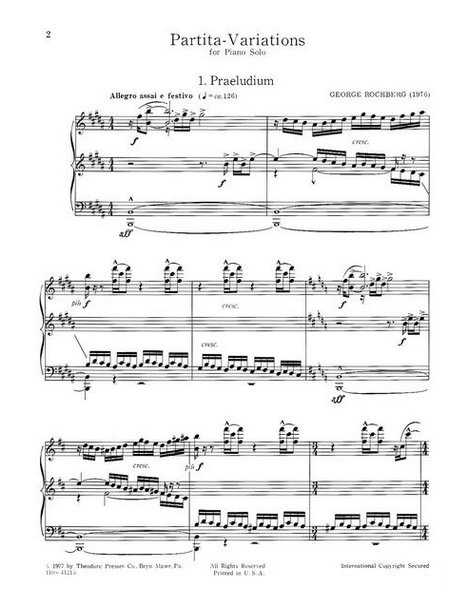

Born in 1918, Rochberg received a bachelor's degree from Montclair State Teacher's College and subsequently enrolled at the Mannes School of Music, where he worked with Georg Szell and Leopold Mannes himself. After serving in the military during World War II, Rochberg studied at the Curtis institute until 1947, when he received a Bachelor of Music degree. A year later he received a master's degree from the University of Pennsylvania and returned to the Curtis Institute to teach. Impressed by the power of serial music during a 1950 stay at the American Academy in Rome, he befriended 12-tone composer Luigi Dallapiccola. Rochberg then began to explore twelve-tone procedure in his own music, eventually producing a string of expressive works in that language, including the Second Symphony, (1956), and the Twelve Bagatelles for Solo Piano, (1952). Also from the 1950s come a number of important theoretical treatises on aspects of twelve-tone technique, specifically the ramifications of what is known in modern music theory as the hexachord. By the early 1960s Rochberg was becoming increasingly frustrated with the limitations of strict serialism, and his last truly twelve-tone work, a piano trio, was completed in 1963. Experimentation with quotation (i.e. the presentation of a snippet of older music within a newly composed framework), as in the Music for the Magic Theater, left Rochberg dissatisfied. With the Third String Quartet of 1972, Rochberg publicly rejected the musical status quo, returning instead to a thoroughly tonal idiom, juxtaposed with bitter, often violent atonal music. The slow movement of the quartet is a set of variations composed in a style reminiscent of Beethoven, while the finale seeks to replicate Mahler. While the quartet was hailed by some as a masterpiece and as the best hope for music in the future, others were less impressed, seeing instead a motley compilation of stylistic cliches which added up to something less than the sum of its parts. Masterful performances by the Concord String Quartet, for whom many of Rochberg's subsequent chamber works would be written, did a great deal to promote Rochberg's new musical aesthetic. Subsequent works, often cast in staggeringly large molds, such as the 50-minute, seven-movement Piano Quintet of 1975, follow in much the same vein as the Third Quartet.

During his long career Rochberg served in a number of administrative and faculty positions. From 1951 to 1960 he worked for the Theodore Presser publishing house. He maintained a faculty position at the University of Pennsylvania from 1960 until the mid-'90s. |

BD: You don’t feel it’s good for audiences to hear

a little bit of discussion?

BD: You don’t feel it’s good for audiences to hear

a little bit of discussion? BD: Do you ever do any conducting?

BD: Do you ever do any conducting? GR: Mostly. There are some which I think

are terrible, but no point in mentioning which ones they are. But for

the most part I’ve been very lucky, very lucky. Of course, one of the

advantages these days of the recording industry and the whole electronic

process of recording is that composers are generally invited to, as they

say, “supervise” recording sessions. So by now I’ve been at I don’t

know how many, and usually, of course, those are the ones that I feel best

about because I had a lot of input. As it turns out, it’s rare that

I end up feeling, “Well, that’s really not it.” One can change one’s

mind, you know. You can have another feeling about how it came out,

not in a sense that you made a mistake, but that your feeling about it is,

“Well, if I could do it now, I would do it differently.”

GR: Mostly. There are some which I think

are terrible, but no point in mentioning which ones they are. But for

the most part I’ve been very lucky, very lucky. Of course, one of the

advantages these days of the recording industry and the whole electronic

process of recording is that composers are generally invited to, as they

say, “supervise” recording sessions. So by now I’ve been at I don’t

know how many, and usually, of course, those are the ones that I feel best

about because I had a lot of input. As it turns out, it’s rare that

I end up feeling, “Well, that’s really not it.” One can change one’s

mind, you know. You can have another feeling about how it came out,

not in a sense that you made a mistake, but that your feeling about it is,

“Well, if I could do it now, I would do it differently.”A select few of the many recordings

of music by George Rochberg

which also have music by some of my other interview guests . . .

To read my Interview with Robert Palmer, click HERE. To read my Interview with Roque Cordero, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Bernard Heiden, click HERE. To read my Interview with Elliott Carter, click HERE.

To read my Interview with William Bergsma, click HERE. To read my Interviews with Gunther Schuller, click HERE. To read my Interview with William Schuman, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Isaac Stern, click HERE. To read my Interview with André Previn, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Miklós Rózsa, click HERE.

To read my Interviews with Zubin Mehta, click HERE. To read my Interview with Jacob Druckman, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Maurice Wright, click HERE. To read my Interview with Joseph Schwantner, click HERE. To read my Interview with David Gordon, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Miriam Gideon, click HERE. To read my Interview with Ursula Mamlok, click HERE. To read my Interview with Yehudi Wyner, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Lowell Lieberann, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Harold Shapero, click HERE. To read my Interview with Andrew Imbrie, click HERE. To read my Interview with Cecil Effinger, click HERE. To read my Interview with Lukas Foss, click HERE.

To read my Interview with John Harbison, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Robert Muczynski, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Ned Rorem, click HERE. To read my Interview with Menahem Pressler, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Neva Pilgrim, click HERE. To read my Interview with Ernst Krenek, click HERE. To read my Interview with Richard Wernick, click HERE.

To read my Interview with George Crumb, click HERE. To read my Interview with John Cage, click HERE. To read my Interview with Phyllis Bryn-Julson, click HERE. |

This conversation was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on March 11,

1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that year, and again in

1988 and 1998; also on WNUR in 2007 and 2013. A copy of the unedited

audio was placed in the Oral History of American

Music archive at Yale University.

This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that

time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.