Conversation Piece:

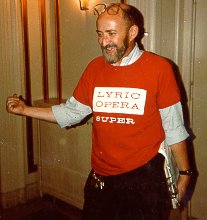

Captain of Supers KEN RECU

By Bruce Duffie

Conversation Piece:

Captain of Supers KEN RECU

By Bruce Duffie

When we watch (and listen) to a theatrical production, our concentration is, naturally, on the principal players, and often on the scenery and stage mechanics. Occasionally there will be an outstanding "Cameo" appearance, which in opera is done by a comprimario singer. But the whole thing would be somewhat shallow if the rest of the scene were not populated by ordinary people. Most of the time, the chorus will take care of that quite nicely, but sometimes you just need more bodies on the stage. In film they're called "extras;" in opera, they are "supernumeraries" or more familiarly, "supers."

The word "super" can be either a noun or a verb. Supers are the spear-carriers, the rabble, the army, the bystanders. When you super, you never sing or make any kind of verbal sound, but you are what makes the difference between a chamber scene and a Grand Spectacle. And just like in real life, somebody's got to organize and run this piece of the opera fabric. At Lyric Opera of Chicago, Ken Recu (pronounced REH-cue) did just that from 1977 through 1983. The task was delegated to him and began to grow - not only because of the growing demands of the directors, but also because of his own enthusiasm.

As an automotive engineer by trade, Recu developed a huge interest in

opera long before actually setting foot on the stage, and this ebullience

has stayed with him several years after retiring from this often-overlooked

position. We had been friends for a long time (though I, myself have

never supered), and I finally asked him to chat with me (and a tape recorder)

about the ins and outs of his specialty. We both rambled and got off

the track many times, but here is much of what was discussed.

Bruce Duffie: We read that many years ago, guys would just show up at the stage door before the show and be hired on the spot for that night. I trust that is not the case these days.

Ken Recu: Hardly. We're needed for the whole rehearsal schedule, depending on what the director has in mind for the use of supers. During my decade, I noticed that supers were used more and more for intricate and complex play-off between supers and major singers. Opera has become the directors' playground, and the trend is to use everyone more for the action. Regulars were paid $5.00 per call, and the call could be a short rehearsal, a costume fitting, or a performance. Eventually, I ran the whole operation using a card file, so I could be at my other jobs and check in with the opera house. In the event of a schedule change, I could phone 20 guys and take care of it. Later, I would have a sheet for each show and not have to sort through cards each time. Now it could easily be done with a computer.

BD: So how do these people get hired in the first

place?

Recu (center) as one of the Swiss Guards in Tosca

KR: You go to a "Casting Call." The director looks at a group to pick out ten soldiers, for instance. One's too fat and another's too thin and another's too old or whatever, but they get ten guys who will fit the costumes. That's the important thing because wardrobe doesn't like altering costumes all the time for supers. Eventually, I knew my people and could produce whatever special type the director was looking for. When you are picked, you go upstairs and get a costume and a rehearsal schedule. Depending on the director, that could be 3 or 4 rehearsals, or 15 rehearsals before opening night. There might be two on a day - 5 PM to 7 PM, then a break and again from 8 PM to 10 PM. Big shows with lots of crowd scenes would need these. For Boris Godounov, we had a week of double calls. That's why a big show would generally open the season so there's nothing else being rehearsed at that time. However, unless the director is really good, he has more time than he knows what to do with. I got to know some directors very well, and many were wonderful to work with. Others were awful. I preferred working with those who had a game-plan before they got there, rather than those who stood and "created great art" as they wasted time at rehearsal. My supers would sit in the auditorium and read, but they were paid for the call!

BD: Is that the difference between a good and a bad director?

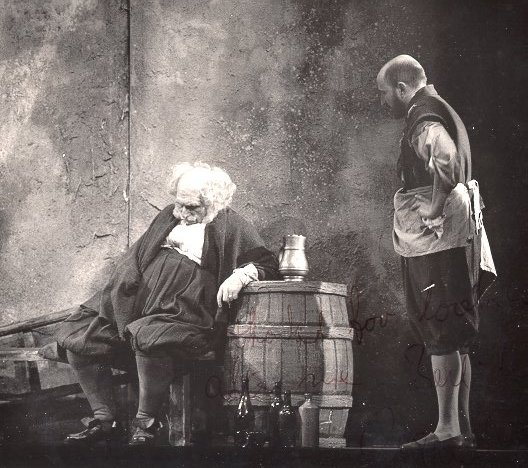

KR: Bad directors figure that supers have nothing else to do in their lives other than super. To be a good director, one needs an understanding of what motivates people, and also a good sense of humor and knowledge of the material. I remember Tito Gobbi would say, "Engage this space over here." A group marching on and off by themselves is one thing, but when the supers interact with the principals, it requires more rehearsal. The waiters in La Bohème, for example, had to play the scene with them, so when the principals rehearsed the second act, you have to have the waiters there to serve the food. As the Captain, I could put myself into any show I wanted, provided the costume fit and the director approved, so I was the Head Waiter once [see photo below]. Anyway, the piano run-through is important because that's the first time you'd work in costume and under the stage lights rather than just some work lights. By the way, when I first took over as the Captain of the Supers, there was no set job description, so I figured out what the necessities were. The task was something that management was glad to shove off into a corner someplace and hope it ran OK. I decided that I'd be in the house any time a super was working.

Recu (center) as the Head Waiter in Act II of

La Bohème,

with Italo

Tajo as Alcindoro and Elena Zilio as Musetta

BD: Were they glad that you took such an interest in the job?

KR: I was told several times that they were glad I was running the Super Department because they knew then they'd have supers!

BD: Did you decide how many to hire?

KR: No. How many go into each show is a function of the director. He will send a list - hopefully earlier rather than later - of the requirements. After they worked with me once or twice, some directors would send specific lists of how many they needed and what special ideas they had, and I'd have specific supers in mind for that show. But the director might not pick those I'd selected. Once, Nathaniel Merrill even asked me to pick the ten soldiers since he knew my guys were good. But I insisted he had to do the picking. When I took a backstage tour of the new Met in New York, Merrill was walking by and said, "Hi, Ken." The rest of the tour group flipped out, and the docent leading the tour asked me who it was, and I said it was the director of that night's performance! He was a pleasure to work with. Anyway, the director decides what he's going to use supers for and how he's going to use them, and that is what really controls how many rehearsals there are, and how intense they will be. Once in awhile, they are mentioned in the libretto, like the Hairdresser in Der Rosenkavalier. I'm not sure if it's specified that there be eight Hungarian Officers, but that's how many costumes there were. In Verdi's Falstaff, you have to have four guys to lift the basket because Alice Ford calls Ned, Will, Tom, and Isaac. The character of Ambrosio in Rossini's Barber of Seville can be sung, or if the music is cut, it can be played by a super. In Carmen, you can have 10 or 80 lance dragoons. How many soldiers you use in Aïda depends on how many you have room for.

BD: So it's not a case of budget consideration?

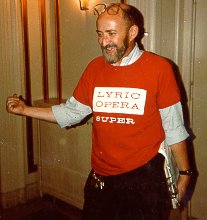

KR: It is if you're building a new show and are deciding how many costumes you'll build. If you borrow a production, there are a certain number of costumes and you can use up to that number. I needed about 50 supers in Boris for soldiers and policemen and others. But the audience doesn't come to see marching soldiers, they come to see and hear the principals. The supers only add spectacle, so you want to get all those costumes out onstage all the time. Production values must be maintained, so if someone couldn't be there on a given night, I'd get a substitute. Pretty soon, I had a free hand in doing that because the directors and stage managers knew that anyone I got would be good. A lot of times I'd do it myself, so I got to do a lot of roles. I had my first solo as the Innkeeper in Falstaff with Sir Geraint Evans [shown in photo below]. He was a pleasure to work with and just that little bit of experience working one-on-one with the director taught me a great deal about stagecraft. It gave me great insight. When I became Captain, I decided to build a nucleus of good, reliable people. I started with 25 regulars and by the time I left there were 40. When someone would call me about becoming a super, I could tell in the first 30 seconds whether they were any good or not.

Recu (right) with Sir Geraint Evans in Act III of Falstaff

The inscription reads: Thanks for looking

after me. Best wishes, Geraint

BD: Were you looking for knowledge or enthusiasm?

KR: A little of both.

KR: A little of both.

BD: So how did you actually get started?

KR: After being in the audience at Lyric since its very first performance in 1954, I eventually supered myself. In the middle of the 1973 season, they needed extra soldiers for Carmen, so I answered an ad on the radio knowing full well that I'd be hooked, and I was. We were paid $2.00 per call, and I was asked back for the next production, which was Der Rosenkavalier. I was one of the Hungarian Officers with the fancy white jackets and the boots and the horsehair cape hung over one shoulder, and the coin purse, white gloves and scimitar [shown at right]. The costume was a knockout. You wanted to rent a horse, ride up Rush Street, go into a bar, take the sword out and clear the glasses away, grab a bottle of Vodka, break the neck off, drink some, give it to your buddy, throw some gold coins at the bartender (who would be cowering, terrified), and then ride off in a blaze of glory! I also worked La Bohème that year, which was Pavarotti's debut at Lyric and the American debut of Ileana Cotrubas. The next year I was asked back as a regular, since I knew so much about opera. Some of us were real opera junkies, and others knew next to nothing about it. I supered through the 1976 season, and the following year, they asked me to be Captain, a position I held through the 1983 season.

BD: Do a lot of people want to be supers? I heard an ad once which touted the novelty of standing on the stage next to Pavarotti.

Recu (left) in Rigoletto with Donnie Rae Albert as

Monterone, and Pavarotti as the Duke

KR: You get some people who want that, but not as many as you would think. During my last couple years, they were knocking the door down, but that wasn't what I wanted. I needed people who would stand next to Pavarotti one night and next to Joe Dokes the next night because they love the artform and not necessarily the singer. The one thing that makes a good super is reliability. That's all. They have to show up on time, all the time. If you can't march, we'll teach you to march. If you can't stand up straight, maybe we can teach you to stand up straight. If you have an open mind and can follow instructions, a good director can get you to do what he or she wants. You do need the ability to take direction from a director and be able to step outside of yourself so that you can watch yourself do something. Some people have that ability and some don't. There is a natural feel to that. By the end, my guys were so loyal that they'd do whatever it took to be there at odd times when necessary. It was my responsibility to disseminate the schedules as best I could so they could arrange their lives around what was needed. In return for that loyalty, I initiated the policy of putting the regulars' names into the program. I had one who was a lawyer, who'd tell his secretary he was going to court. He'd then jump in a cab, get out of his suit coat and vest, put on his rehearsal tee shirt, and be ready to go. When the call was over, he'd go back to the office. I had guild members who were contributors to the company. One guy would donate his check back to Lyric, and it amounted to $400 or $500.

BD: Would the regulars be in every opera in a season?

Recu (right) in Gluck's Orfeo

KR: In a season with 8 operas, they might wind up in 4 or 5. But even with the advanced pay, they must not rely on supering for the rent. Supers have to have other livelihoods, and just want to contribute or experience it firsthand. I initiated the method of paying at the end of the run of each show. Nothing was withheld; it was looked at as an honorarium. We left it to the individuals to report the income for tax purposes. When the company went to computer, supers were vendors supplying a service. As Captain, I had a salary.

BD: Are there any operas where there are no places for supers that you wish had at least an indication for them so they could be used?

KR: Directors come up with that all the time.

We had 30 guys in Salome who came out to open the cistern by physical

force. Out of the sightlines there were crew members operating a counter-weighted

winch, but it looked like all of us who were barefoot and dressed in burlap

were actually lifting this massive grate which covered the cistern.

These 30 are in addition to the three that Herod calls by name at the end

to extinguish the torches. For the big scene in Boris, the tenor

singing Dmitri was brought in on a litter. He told me that at the Metropolitan

Opera in New York, the litter was perched on a riser so the supers could

just walk under and pick it up at shoulder-height after he walked up a few

steps to get on.  Here in Chicago, my guys could pick it up from the floor with him on it,

and that really impressed him. During the Inn Scene, the character

tenor, Florindo Andreolli,

was Missail, and he would do something different every night and you'd learn

to play off of him. One night, he picked up a chair and threatened

me with it. There was a great deal of chasing and running around.

I went out through the window in that scene [shown at right].

Another guy who would surprise you was Nicolai Ghiaurov.

In the ballet scene in Khovanschina, I stood behind him when he sat

on the couch and had his mead-pot. Usually he would reach out with

his cup and I'd refill it, but one night he tossed the cup and I caught it.

[Note: In a very recent interview with the Ballet Master Maria Tallchief, she

also mentioned that Ghiaurov was particularly adept at gracefully interacting

with her corps.] In the Lohengrin in 1980, the director used

26 guys who had to stand absolutely motionless for almost the entire first

act, each holding a 15-foot lance. They also had to wave and drop and

raise their lances on cue to the music. It looked beautiful from the

audience, but it was some of the toughest duty you could do. We had

a lot of tough things, and that was definitely the longest.

Here in Chicago, my guys could pick it up from the floor with him on it,

and that really impressed him. During the Inn Scene, the character

tenor, Florindo Andreolli,

was Missail, and he would do something different every night and you'd learn

to play off of him. One night, he picked up a chair and threatened

me with it. There was a great deal of chasing and running around.

I went out through the window in that scene [shown at right].

Another guy who would surprise you was Nicolai Ghiaurov.

In the ballet scene in Khovanschina, I stood behind him when he sat

on the couch and had his mead-pot. Usually he would reach out with

his cup and I'd refill it, but one night he tossed the cup and I caught it.

[Note: In a very recent interview with the Ballet Master Maria Tallchief, she

also mentioned that Ghiaurov was particularly adept at gracefully interacting

with her corps.] In the Lohengrin in 1980, the director used

26 guys who had to stand absolutely motionless for almost the entire first

act, each holding a 15-foot lance. They also had to wave and drop and

raise their lances on cue to the music. It looked beautiful from the

audience, but it was some of the toughest duty you could do. We had

a lot of tough things, and that was definitely the longest.

BD: I talked with Hans Sotin who was singing King Henry in that production, and he mentioned that he was scared to death that he might accidentally get clobbered by one of those lances.

KR: I can understand the trepidation. Plus the costumes were warm and one guy fainted at a rehearsal. The chorus lost some people, and one of the trumpets walked off the stage one evening after feeling like he was going to lose it. One of the things you learn how to do as a super is to stand. You learn right away not to lock your knees. You can then shift your weight from one knee to the other, and depending on the costume, you can do a lot of surreptitious moving around. Sometimes it can get boring. In one of my early seasons, during Favorita I had to stand there and hold a lance for 23 minutes! I could see the clock behind the conductor in the pit, so I knew it was all of 23 minutes! It's largely a function of the director and how innovative he is with the supers, within in the constraints of the period of the piece. For me, it should be theatrical.

BD: Did you ever have someone move from super to chorus?

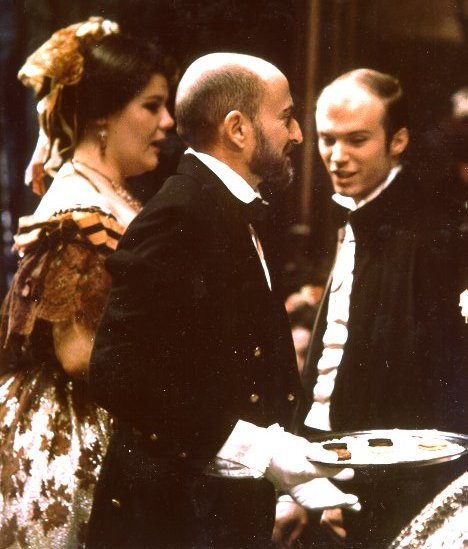

Recu (center) serving the guests at Violetta's party in

La Traviata

KR: Rarely, but because of the people I was getting, there started to be a lot more rapport with the chorus. One of my guys even married a chorister! Occasionally a principal singer will be asked to make an appearance in a scene where there is no singing to be done, and that's supering. As Ulrica, Beverley Wolff was asked to re-appear at the end of Un Ballo in Maschera with her hand raised indicating that her prophecy has been fulfilled. She had to stay in costume for the rest of the evening just to appear at the end, so we awarded her a sweatshirt making her an honorary super, and she loved it! Whenever she returned to Chicago, she always socialized with us.

BD: Did the supers ever work with the conductor or was it always with the director?

KR: Always with the director. Only rarely did the conductor have anything to do with the supers. I remember in the Faust (which was later televised by PBS) we had to carry the dead Valentin off, and because of the stage set and the ground covering and the slippers we were given, the conductor complained we were making too much noise. So we arranged to go barefoot and just wear black socks. That worked, and we were absolutely silent over the very soft orchestral postlude to the scene. I had worked with the baritone previously, so he know I would have guys who wouldn't drop him. The bass who sang Abimilech in Samson weighed 235 pounds, and we had to get to him, fold his arms over his chest, put his whip on top of him, cover him with a cloth, pick him up from far downstage and get him into the temple - all in about 45 seconds of music, and make it look stately! And our own costumes could easily get tangled up in his arm, so it was fraught with danger. When I saw the tape from the San Francisco production, the guys who carried Abimilech off didn't wear those particular costumes - theirs were much simpler and didn't have the decorative streamers. Live theater is the most exciting thing you can do. Every performance is different. Out front, they don't know that. We want to make it the same every time, but it's always going to be different.

[To see more pictures of Recu in costume, click HERE.]

* * * * *

Now in his 20th year at WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago, Bruce Duffie

spent the first week of August in Beijing, China, traveling with an orchestra

that merged with Chinese musicians for a Cultural Exchange. Next time

in The Opera Journal, an interview with the distinguished stage director

Bodo Igesz on his 60th

birthday.

* * * * *

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on July 18, 1985. The transcription was made and published in The Opera Journal, #4, 1994, and subsequently posted on this website. Photos have been added for this presentation, and to see more pictures of Recu in costume, click HERE.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.