|

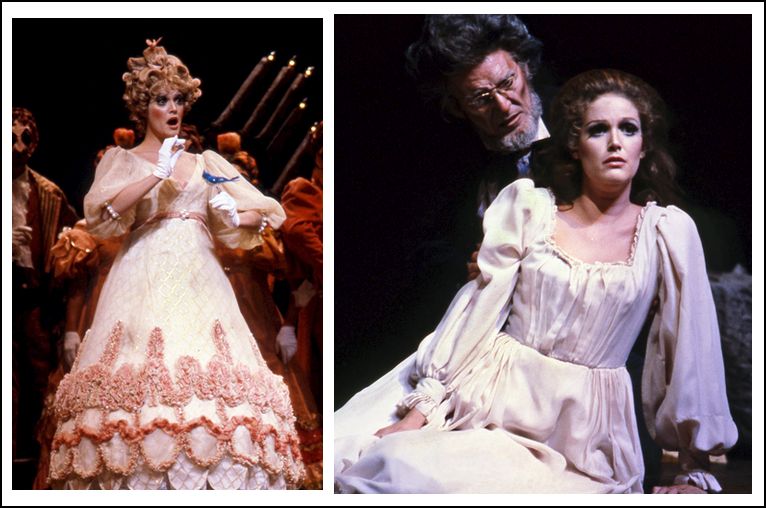

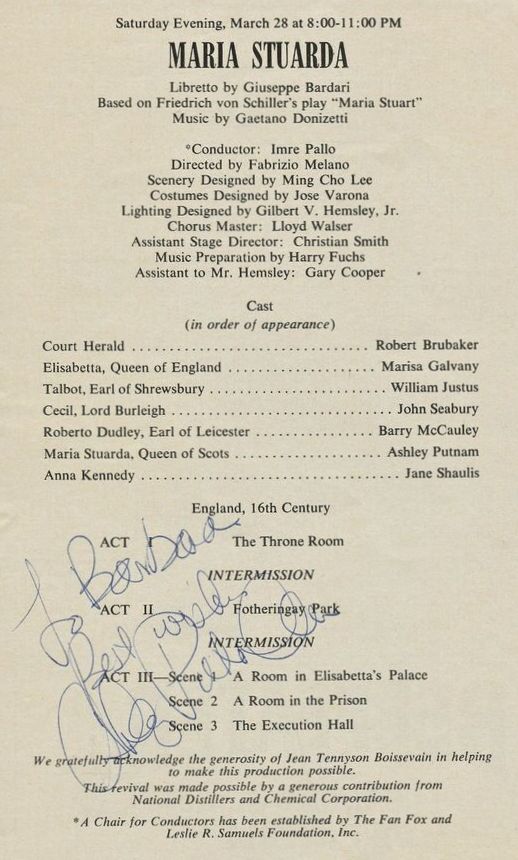

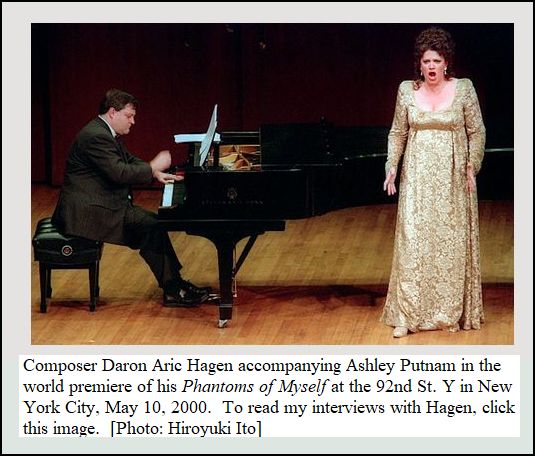

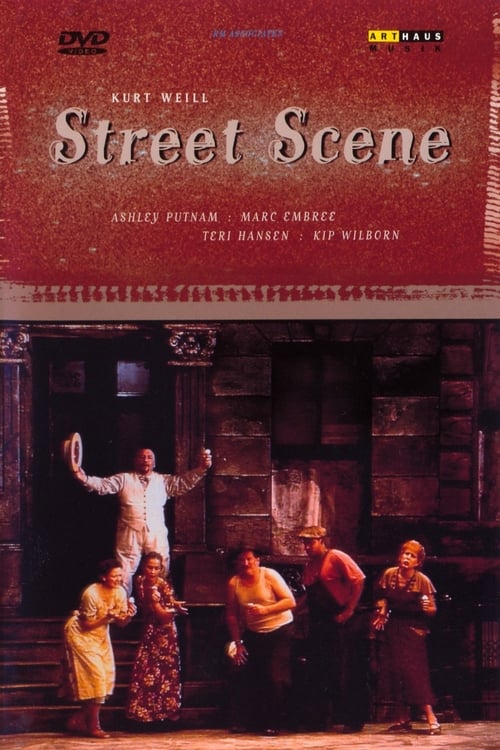

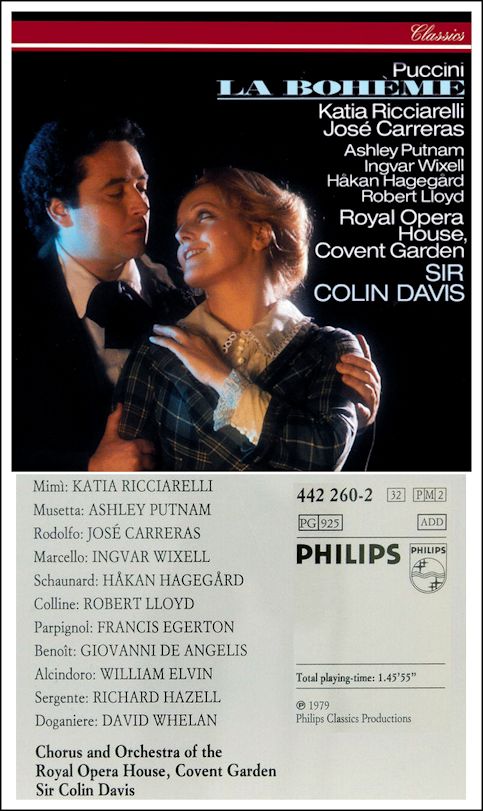

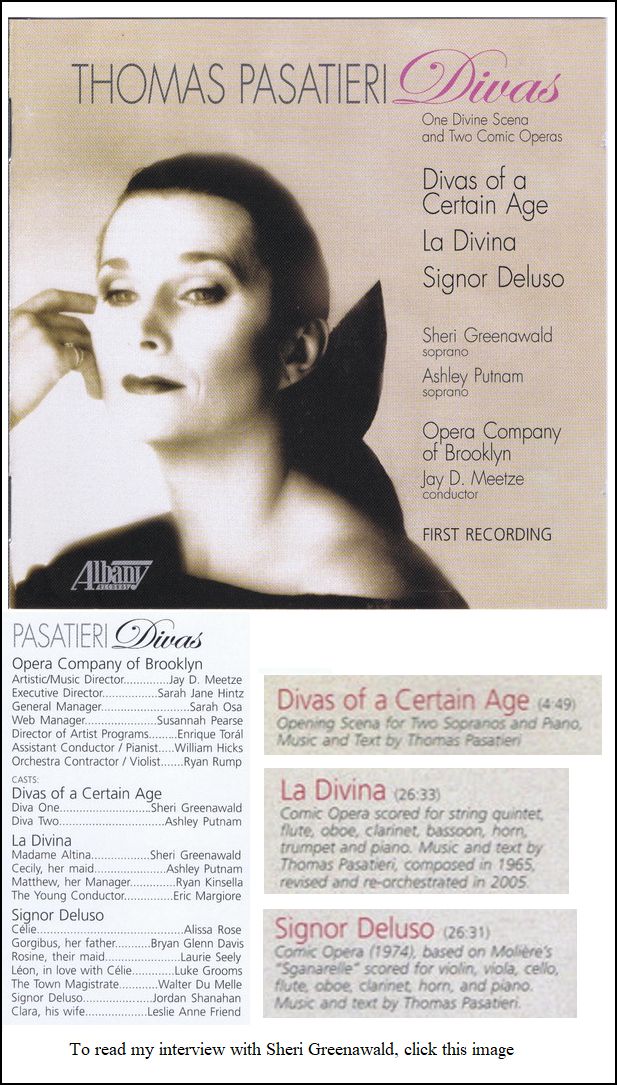

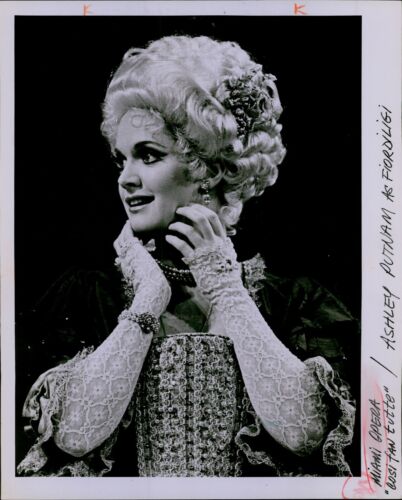

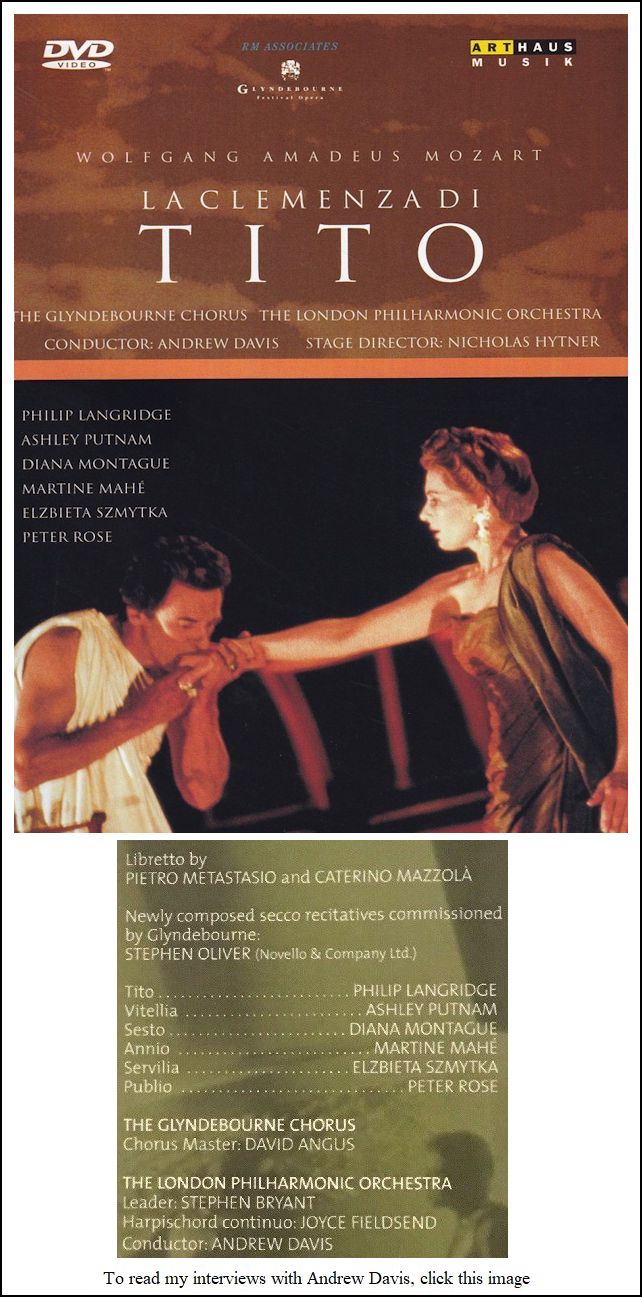

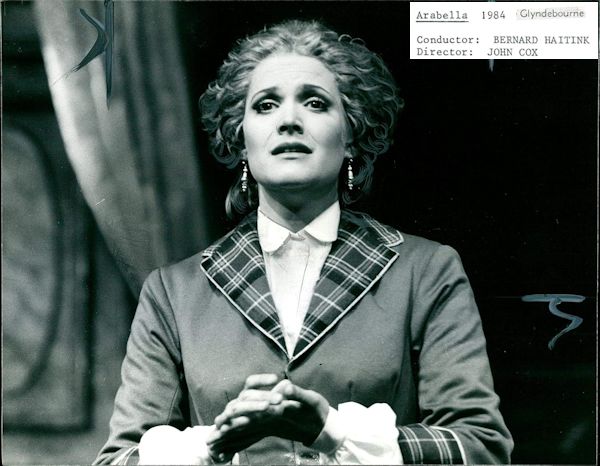

Ashley Putnam (born August 10, 1952) is an American soprano from New York City. Her professional singing career began in 1976 and has spanned over 30 years. She began her music career playing the flute. Her mother was an amateur singer and was a regular soloist at the church where she also sang in the choir. The young Ashley began playing the flute and attended the Interlochen Center for the Arts in the summers during high school. Upon graduation from high school, Ashley enrolled at the University of Michigan School of Music as a flute major. There she sang in the university choirs and realized she had vocal potential when she was given solos in choir. She soon switched to a vocal major, and in 1973, was an apprentice singer with the Santa Fe Opera during its summer festival. She completed her Bachelor of Music degree program in May, 1974, and then began her graduate studies at UM. She returned to Santa Fe's Apprentice Singer Program in the summer of 1975, and then finished her Master of Music degree in December. She studied singing with Ellen Faull, and in the spring of 1976 was one of two winners of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. After winning the MET Auditions, Ashley's career took off. Her operatic roles have included Violetta (La traviata), Mimì and Musetta (La bohème), Lucia (Lucia di Lammermoor), Arabella (Arabella), Fiordiligi (Così fan tutte), Vitellia (La clemenza di Tito), Anna Maurrant (Street Scene), and many others. She also gave memorable performances in contemporary operas, including the American premieres of Musgrave’s Mary Queen of Scots and Henze’s Das Verratene Meer. She also sang Czech repertoire, performing Jenůfa, Kat'a Kabanová, and Rusalka. In addition, she was invited to sing at the White House for Presidents Carter and Reagan. Known for her wide-ranging repertoire, expressive acting, and glamorous presence, Putnam has performed in the world's most prestigious opera houses, including Covent Garden, Vienna Staatsoper, Berlin Staatsoper, La Fenice, and in the US, the Metropolitan Opera, Chicago Lyric Opera and San Francisco Opera. Her concert credits include performances with the New York Philharmonic, the Concertgebouw, and the San Francisco Symphony. Putnam is now [2024] a member of the voice faculty at the Manhattan

School of Music, and has a private studio in New York. She has taught masterclasses throughout

the country, adjudicates for the Metropolitan Opera National Council

Auditions, and has served on the voice faculties of DePaul University

and the Eastman School of Music of the University of Rochester. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 20, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later in the year, and again in 1997. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.