A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

FP: That is a problem in many cases, yes.

The listening? No, it’s not only audiences or the lay audience, but

a lot of critics. I don’t think they have the patience, or they can’t

sit down and listen to a piece through that’s more than three minutes or five

minutes or seven minutes. It becomes too long. Whenever we write

a piece, it has to have a beginning, a middle, and a conclusion, and it has

to end when it’s ready to end, not because three minutes is up or seven minutes

or half an hour is up. I’ve written pieces, long involved works.

A few years ago I wrote a cello concerto which is about a half an hour long,

which is a long piece by today’s standards. Not a dramatic piece, not

an opera, but a concerto! Max Rudolf, who is a fabulous

musician in my opinion, has been an influence on me for the past twenty years

or so. He’s retired now, but he says to me, “Whatever you write, send

it to me. I want to hear it.” I trust his judgment because he

made his mark doing Beethoven and the German repertoire, but he’s very open-minded.

He listens to the most crazy jazz piece with the same ears that he listens

to the Eroica. I was very concerned

about the cello concerto because the assignment was for twenty minutes, and

here it was half an hour. He wrote back that he liked the piece very

much. He said the only trouble was it ended too soon. I’m thinking,

it ended too soon??? What do you mean? So he said, “It felt to

me like you had to end the piece because of time constraints.” I said,

“You are absolutely right,” and he said, “You shouldn’t let that happen.”

FP: That is a problem in many cases, yes.

The listening? No, it’s not only audiences or the lay audience, but

a lot of critics. I don’t think they have the patience, or they can’t

sit down and listen to a piece through that’s more than three minutes or five

minutes or seven minutes. It becomes too long. Whenever we write

a piece, it has to have a beginning, a middle, and a conclusion, and it has

to end when it’s ready to end, not because three minutes is up or seven minutes

or half an hour is up. I’ve written pieces, long involved works.

A few years ago I wrote a cello concerto which is about a half an hour long,

which is a long piece by today’s standards. Not a dramatic piece, not

an opera, but a concerto! Max Rudolf, who is a fabulous

musician in my opinion, has been an influence on me for the past twenty years

or so. He’s retired now, but he says to me, “Whatever you write, send

it to me. I want to hear it.” I trust his judgment because he

made his mark doing Beethoven and the German repertoire, but he’s very open-minded.

He listens to the most crazy jazz piece with the same ears that he listens

to the Eroica. I was very concerned

about the cello concerto because the assignment was for twenty minutes, and

here it was half an hour. He wrote back that he liked the piece very

much. He said the only trouble was it ended too soon. I’m thinking,

it ended too soon??? What do you mean? So he said, “It felt to

me like you had to end the piece because of time constraints.” I said,

“You are absolutely right,” and he said, “You shouldn’t let that happen.”

Frank Proto was born in Brooklyn,

New York in 1941. He began piano studies at the age of 7 and the double bass

at the age of 16 while a student at the High School of Performing Arts in

New York City. After graduating he attended the Manhattan School of Music

where he earned his bachelor's and master's degrees. As a student of David

Walter, Frank performed the first solo double bass recital in the history

of the school. As a composer he his self-taught. For his graduation recital

in 1963, Proto confronted the typical bass player’s problem - there was very

little literature for the instrument. He programmed a baroque work, a romantic

piece, and an avant-garde composition using electronic tape, but he wanted

a contemporary composition in a more American style. Unable to find one he

liked, he decided to write his own. The resulting piece — Sonata 1963 for Double Bass and Piano

— was his first composition. It has subsequently been performed hundreds

of times worldwide by scores of bassists, and has entered the standard double

bass repertoire. During the early 1960s Frank earned his living as a free-lance bassist in

New York City, performing with such organizations as the Symphony of the Air,

American Symphony, the Robert

Shaw Chorale, and — as one of the original members — the Princeton Chamber

Orchestra. He also played with various Broadway and Off-Broadway show bands

and in many of the jazz clubs that were a mainstay of New York nightlife

at the time.

During the early 1960s Frank earned his living as a free-lance bassist in

New York City, performing with such organizations as the Symphony of the Air,

American Symphony, the Robert

Shaw Chorale, and — as one of the original members — the Princeton Chamber

Orchestra. He also played with various Broadway and Off-Broadway show bands

and in many of the jazz clubs that were a mainstay of New York nightlife

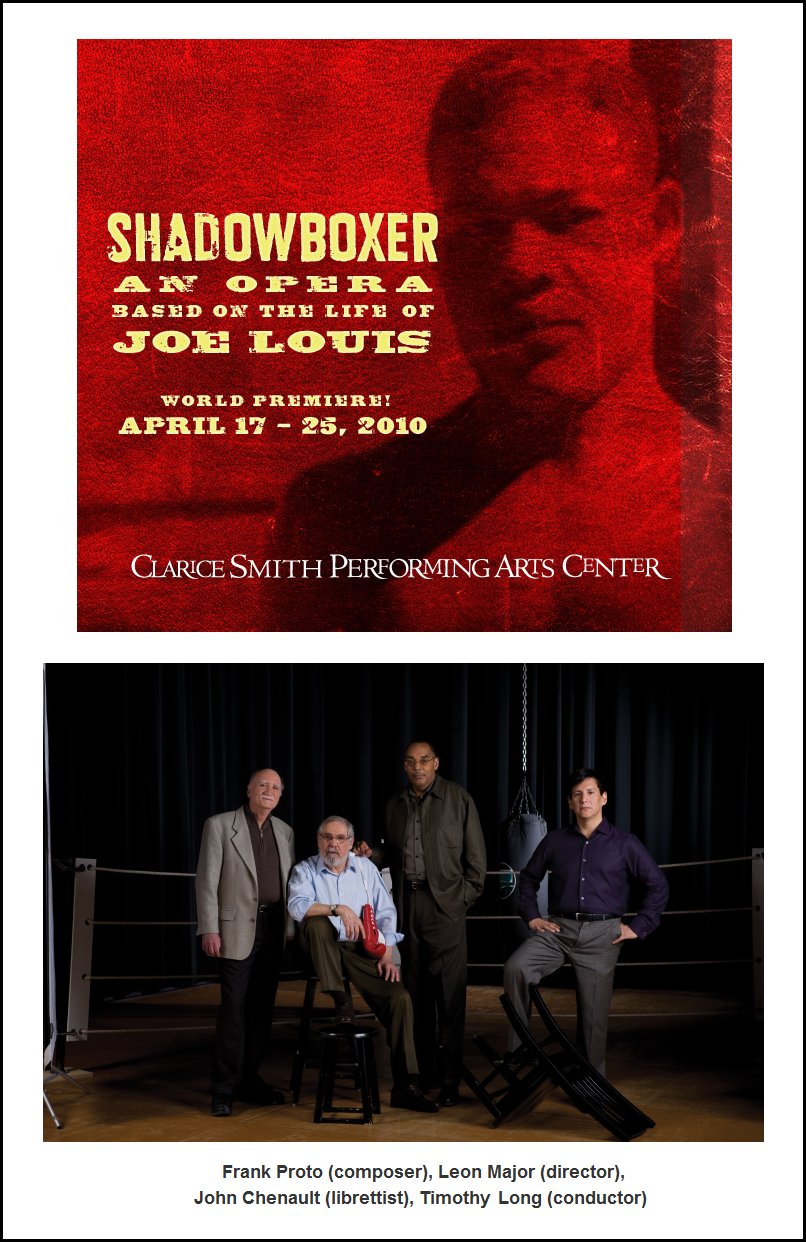

at the time.In 1966 he joined the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra where, with the help and encouragement of CSO Music Directors Max Rudolf and Thomas Schippers, he began to bloom as a composer. The early opportunities given him by the CSO to compose and arrange for the orchestra resulted in a 30 year stay in which the orchestra premiered over 20 large works and countless smaller pieces and arrangements composed for Young People’s concerts, Pop’s concerts, tours and special occasions. Frank was appointed Composer-in-Residence by Thomas Schippers in 1972 and during his tenure with the orchestra every music director commissioned him to compose works to feature various principal players, visiting guest soloists or the orchestra itself on its subscription concerts, including Max Rudolf (Concerto No. 1 for Double Bass and Orchestra), Thomas Schippers (Concerto in One Movement for Violin, Double Bass and Orchestra, and Concerto for Cello and Orchestra), Michael Gielen (Dialogue for Synclavier and Orchestra), Jesús López-Cobos (The New Seasons for Tuba, Percussion and Orchestra, Hamabe No Arashi and the Music Drama Ghost In Machine.) Writing for the Pops, his Casey at the Bat has been performed over 500 times and has been recorded twice, while his Carmen Fantasy for Trumpet and Orchestra — commissioned and recorded by Doc Severinsen — recently received its 400th performance. His Fantasy on the Saints, An American Overture and Variations on Dixie have become standards in the Orchestral Pops repertoire. Working in such an all-encompassing musical atmosphere, both as a player and a composer, has resulted in Proto being able to become as comfortable with the large orchestra as he is with a jazz rhythm section. The result is as exhilarating as it is natural. He has written music for such artists as Dave Brubeck, Eddie Daniels, Duke Ellington, Cleo Laine, Benjamin Luxon, Sherill Milnes, Gerry Mulligan, Roberta Peters, François Rabbath, Ruggerio Ricci, Doc Severinsen, Richard Stoltzman and Lucero Tena. Since leaving the Cincinnati Symphony in 1997 Proto has continued to work in a wide variety of styles and sizes including the Violin Concerto Can This Be Man? - a Music Drama for Violin and Orchestra for Alexander Kerr, Concertmaster of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam, 3 Divertimenti for Solo Violin for the young virtuoso Eric Bates, Yesterday's News - a Satire for Jazz Band and Actors for the Jazz Band at the University of Cincinnati's College-Conservatory of Music, The Creatures in Room 642 for the Dayton Symphony Orchestra's Young People's programs, Four Scenes after Picasso - Concerto No. 3 for Double Bass and Orchestra for François Rabbath and Paganini in Metropolis for Clarinet and Wind Symphony and/or Clarinet and Orchestra for Eddie Daniels. Proto and Daniels also collaborated on a year-long DVD project: Bridges - Eddie Daniels plays the music of Frank Proto, which features the world premiere performances and recordings of Sketches of Gershwin and Sextet for Clarinet and Strings. The Red Mark DVD/CD was rewarded with a 2008 Grammy Nomination. In 1977 he began a collaboration with the Syrian-French double bass virtuoso François Rabbath. He has written Rabbath four major compositions — with a fifth in the works — with orchestra that span a musical landscape from the most contemporary and serious - Four Scenes after Picasso - to the most unusual Carmen Fantasy that anyone is likely to encounter. Rabbath, whose musical appetite is as wide-ranging as Proto’s has recorded all of the pieces and continues to perform them worldwide. In 1993 Proto began another collaboration — with poet, playwright and author John Chenault. To date they have written eight works together, the most notable being Ghost in Machine - an American Music Drama for Vocalist, Narrator and Orchestra. Commissioned by the Cincinnati Symphony for the its 100th anniversary in 1995, the work brought Proto and Chenault together with the vocalist Cleo Laine and actor Paul Winfield for the first time. Ghost is a work that is not easily pigeon-holed. It is a large-scale orchestral work that uses elements from a wide spectrum of the musical landscape woven around an equally wide-ranging text that explores contemporary society’s problems with racism, religious intolerance and gender warfare. The success of Ghost resulted in two new commissions for the pair. The Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C. commissioned a work for Cleo Laine to celebrate the new millennium. The result - The Fools of Time - is a jazz-based work and was premiered in February 2000. At the other end of the musical spectrum is My Name is Citizen Soldier, commissioned by the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra to celebrate the orchestra’s 10th anniversary and the opening of the National D-Day Museum in New Orleans. The work, a tribute to the veterans of World War II, was premiered in September 2000 with actor Paul Winfield as the soloist. Working with Chenault has brought an added dimension to Proto’s music — the visual. Their pieces bring a more all-encompassing, quasi theatrical experience to audiences. Together they have explored various ways to utilize the orchestra in ways beyond the traditional. Their techniques have enabled them to bond in new ways with audiences, resulting in spectacularly-successful performances. Their most recent collaboration, The Tuner, a Musical Prophecy in Seven Scenes for Vocalist, Actors and Musicians, is a musical what if centered around the events of the present time. In 2009 the pair finished their largest project to date: Shadowboxer - an opera based on the life of Joe Louis. Commissioned by the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center and the University of Maryland School of Music, the two-act, two and a half hour production was directed by Leon Major and was given it's premiere production in April of 2010.

Proto believes strongly in maintaining the connection between composing and performing — a tradition that once was the norm but is now the exception outside of the jazz and pop fields. He does not hesitate to pick up his bass to play with a jazz or chamber music group or travel near or far to play a solo recital. "It helps a great deal to experience what a soloist feels when under the lights," he says. Currently in a long-term project to record all of his chamber music for the Red Mark label — Eight CDs and Four DVDs have been released to date, with several more in various stages of production — he continues to maintain his double life as both a composer and performer. In November 2006 Proto was awarded the Grand Prize in the First New Orleans International Composer Competition for his Fiesta Bayou and Kismet. The prize included a commission for a major orchestra work. The Dalì Gallery, a 6-movement, 30-minute orchestral suite based on the paintings of Salvadore Dalì was premiered by the Louisiana Philharmonic, conducted by Klauspeter Seibel on May 7, 2009. Proto is also passionate in his belief that performing artists and composers should not hesitate to tackle the pressing issues that confront society today - the controversial social and political issues that most artists in this supposedly free society of ours are loathe to confront with their art. Examples of his work in this area include the chamber works; Afro-American Fragments (poetry by Langston Hughes), Mingus - Live in the Underworld (Text by John Chenault), Four Rogues - a Mystery for Double Bass and Piano and The Games of October for Oboe and Double Bass (after the Anita Hill, Clarence Thomas Supreme Court hearings). Orchestral works include; Can this be Man?, Ghost in Machine, My Name is Citizen Soldier, Four Scenes after Picasso, and The Profanation of Hubert J. Fort - an Allegory in Four Scenes for Voice, Clarinet (doubling) Tenor Saxophone and Double Bass. Proto composed both the Music and the text for the piece. -- Biography form Liben Publishers

website (with slight corrections, and the addition of links and photos)

|

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on June 15, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1991 and 1996. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2014.To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.