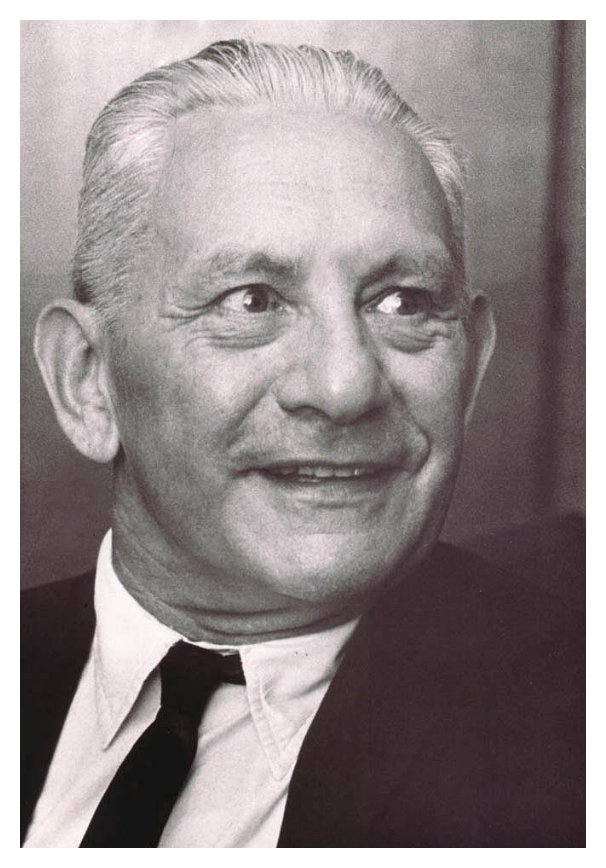

| Paul

Amadeus Pisk was born on May 16, 1893, in Vienna, Austria, and died

on January 12, 1990 in Los Angeles. He earned his doctorate in musicology

from Vienna University in 1916, studying under Guido Adler. Afterwards he

studied conducting at the Imperial Academy of Music and the Performing Arts

graduating in 1919. His teachers there included Franz Schreker (counterpoint).

Pisk also studied privately with Arnold Schoenberg from 1917 to 1919. He

then taught at the Vienna Academy and gave adult education lectures, especially

at the Volkshochschule Volksheim Ottakring, where from 1922 to 1934 he was

director of the music department. He also taught at the New Vienna Conservatory

from 1925 to 1926 and the Austro-American Conservatory near Salzburg from

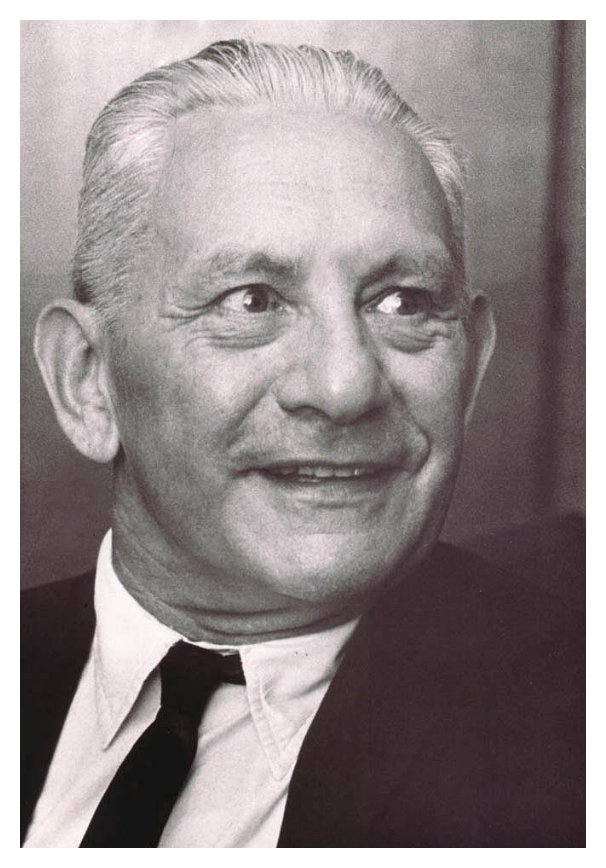

1931 to 1933. He was also a board member, secretary, and pianist in Schoenberg's Society for Private Musical Performances. He was among the founding members of the International Society for Contemporary Music and from 1920 to 1928 was coeditor of Musikblätter des Anbruch and music editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung. Dr. Pisk immigrated to the United States in 1936. He taught at the University of Redlands, where he served four years as director of the music school. He joined the faculty of The University of Texas at Austin in 1951, teaching until his retirement in 1963. After that he was a visiting professor at Washington University in St. Louis until 1972. An internationally renowned composer, he completed thirty-six opuses between 1920 and 1936. The String Quartet, Op. 8, was awarded the Composition Prize of the City of Vienna in 1925. Twenty-four critically acclaimed works were premiered in Europe. He also published operatic, orchestral, ballet, folk dances, ballads, and works for piano and chorus. In addition to his work as a composer, Pisk was a music critic. He co-authored A History of Music and Musical Style, a music theory book. Paul A. Pisk: Essays in his Honor, a collection of 26 pieces written by colleagues and noted musicologists, was published by the College of Fine Arts in 1966. He was awarded a golden doctoral diploma by the University of Vienna in 1967. A prize named in his honor is the highest award for a graduate student paper at the annual meeting of the American Musicological Society. |

BD: Being both a musicologist and a composer, did

understanding musicology help you be a better composer?

BD: Being both a musicologist and a composer, did

understanding musicology help you be a better composer? Gerhard Krapf was born on December 12, 1924 in the small German town of Meissenheim.

After many years of piano and organ instruction, Gerhard was drafted into

the German army in 1942. He was wounded four times during his course of military

service and was unaware that the war had ended when he was captured by the

Russians on May 10, 1945. Years of hard labor followed. During this period

of mental and physical agony, Gerhard began composing. Paper was in short

supply, so he wrote his scores on old cement bags! Although he believed that

his life would end in central Russia, he was freed on July 3, 1948. By 1950k

Gerhard had completed his music education and received the Staatsexamen-Diplom

in organ and music theory from the Hochschufe fur Musik, Karlsruhe.

Gerhard Krapf was born on December 12, 1924 in the small German town of Meissenheim.

After many years of piano and organ instruction, Gerhard was drafted into

the German army in 1942. He was wounded four times during his course of military

service and was unaware that the war had ended when he was captured by the

Russians on May 10, 1945. Years of hard labor followed. During this period

of mental and physical agony, Gerhard began composing. Paper was in short

supply, so he wrote his scores on old cement bags! Although he believed that

his life would end in central Russia, he was freed on July 3, 1948. By 1950k

Gerhard had completed his music education and received the Staatsexamen-Diplom

in organ and music theory from the Hochschufe fur Musik, Karlsruhe.Gerhard then came to the United States to study at the University of Redlands where he received his Master of Music degree in 1951. His limited visa forced him to return to Germany, but he was able to immigrate to the United States in 1953, attaining citizenship in 1959. He taught in Michigan, Missouri, and Wyoming prior to his appointment in 1961 as professor and head of the organ department at the University of Iowa. Following and invitation by the University of Alberta, Canada, he taught at this institution from 1977 to the year of his retirement, 1987. He was renowned for his significant contribution to church music with prolific compositions of organ, choral, and vocal works; for the designing and supervision of the 1978 Casavant organ in Convocation Hall at the University of Alberta; scholarly works on the organ; and a decade of teaching at the University of Alberta (1977-87), for which he was named professor emeritus. He contributed significantly to the development of the graduate programs in keyboard and library resources at the University of Alberta. He died July 2, 2008. |

PP: Not really. Not real composers.

Many people compose but shouldn’t.

[Both laugh] But the young people are the leading composers.

In my time, for instance, Ives was a great composer, and in my opinion Carter

is a fine composer, along with several others. But there are young

people coming up who, I think, have not enough direction. Somebody

composes like the minimalist Philip Glass, and somebody composes like Milton

Babbitt with electronic instruments. [See my Interviews with Philip Glass,

and my Interview with Milton

Babbitt.] So we cannot — at least I cannot — find

a line of continuation historically because there are too many different

paths which are like the strings of a piano when they are loosened.

PP: Not really. Not real composers.

Many people compose but shouldn’t.

[Both laugh] But the young people are the leading composers.

In my time, for instance, Ives was a great composer, and in my opinion Carter

is a fine composer, along with several others. But there are young

people coming up who, I think, have not enough direction. Somebody

composes like the minimalist Philip Glass, and somebody composes like Milton

Babbitt with electronic instruments. [See my Interviews with Philip Glass,

and my Interview with Milton

Babbitt.] So we cannot — at least I cannot — find

a line of continuation historically because there are too many different

paths which are like the strings of a piano when they are loosened. PP: In Vienna was a big daily called the Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers Newspaper). It was an organ

of the Social Democratic Party, and in Vienna I was the representative for

public music from the Social Democratic Party, and was music critic for this

time with the consent of Schoenberg. Schoenberg was very autocratic,

and I had to ask him if I can accept this. He said, “This paper doesn’t

accept the advertising of concerts and concert agents, so you can go there

and be objective.” He knew that I was for new music, and this journal

was very widely read because in Vienna it is a plurality. Still, the

city of Vienna is Social Democratic. So I wrote reviews, sometimes

for Schoenberg — which was kind of audacious

— and several others.

PP: In Vienna was a big daily called the Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers Newspaper). It was an organ

of the Social Democratic Party, and in Vienna I was the representative for

public music from the Social Democratic Party, and was music critic for this

time with the consent of Schoenberg. Schoenberg was very autocratic,

and I had to ask him if I can accept this. He said, “This paper doesn’t

accept the advertising of concerts and concert agents, so you can go there

and be objective.” He knew that I was for new music, and this journal

was very widely read because in Vienna it is a plurality. Still, the

city of Vienna is Social Democratic. So I wrote reviews, sometimes

for Schoenberg — which was kind of audacious

— and several others.This interview was recorded on the telephone on October 22, 1986.

Segments were used (with recordings) on WNIB in 1988, 1993 and 1998.

A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. The transcription

was made and posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.