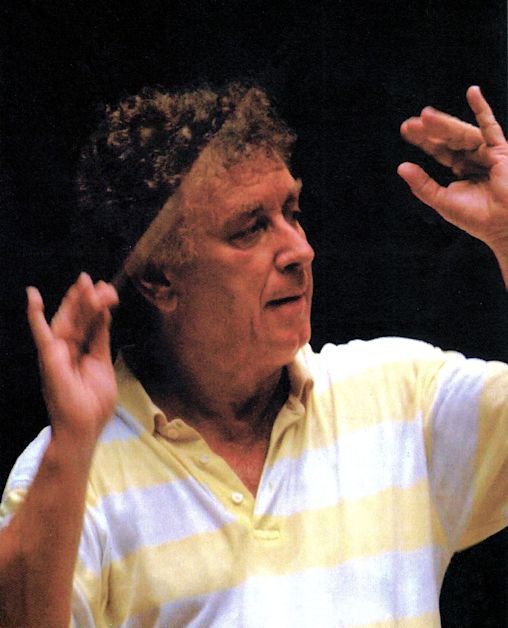

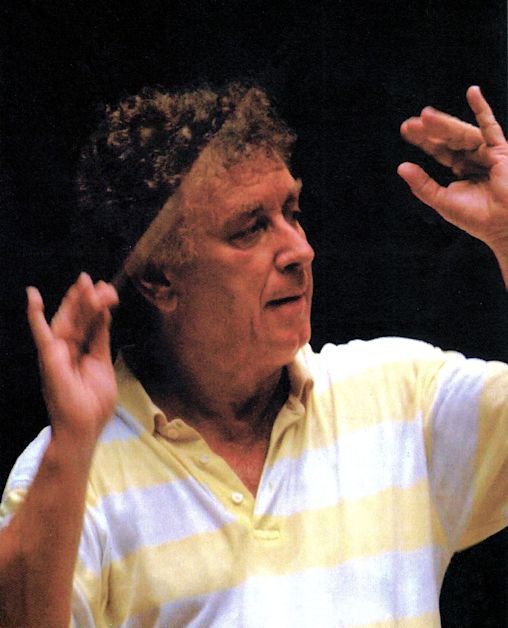

| Christof Perick

is the former Chief Conductor of the Beethoven Orchester Bonn. He

was Music Director of Germany’s Nuremberg Philharmonic and Opera from

2006 through 2011 and Music Director of the Charlotte Symphony from

2001 through 2010. He completed his post as Principal Guest Conductor

of the Dresden Semper Opera at the close of the 2007/2008 season.

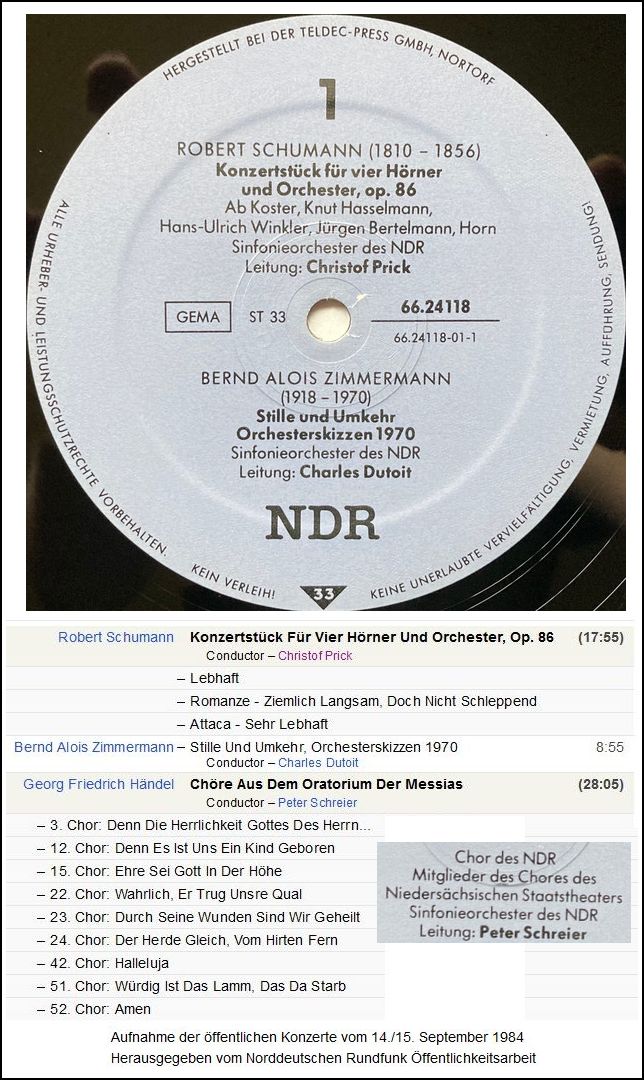

Other former positions include Music Director posts with the Niedersaechsisches

Staatsorchester and Staatsoper in Hannover, Germany from 1993-96; the

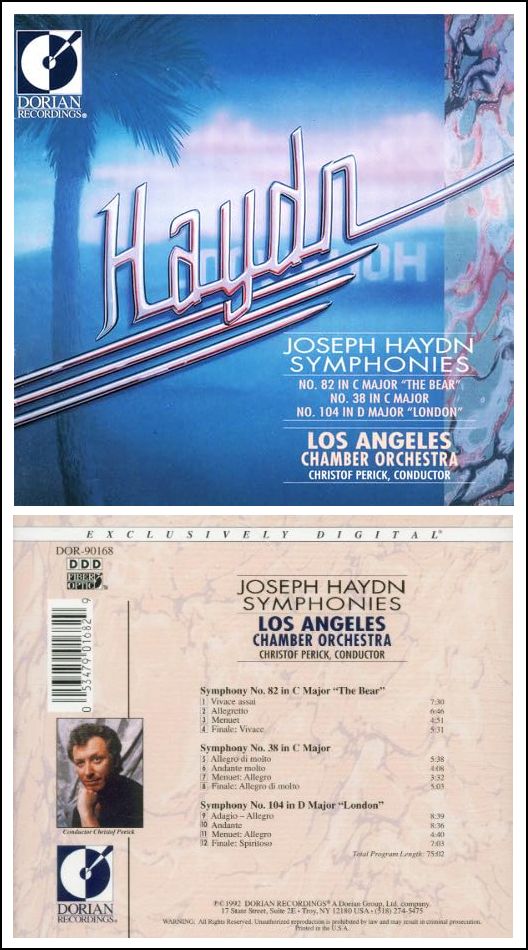

Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra from 1992-95; the Badische Staatskapelle

Karlsruhe, Germany from 1977-1986; and the State Orchestra and Opera Saarbrucken,

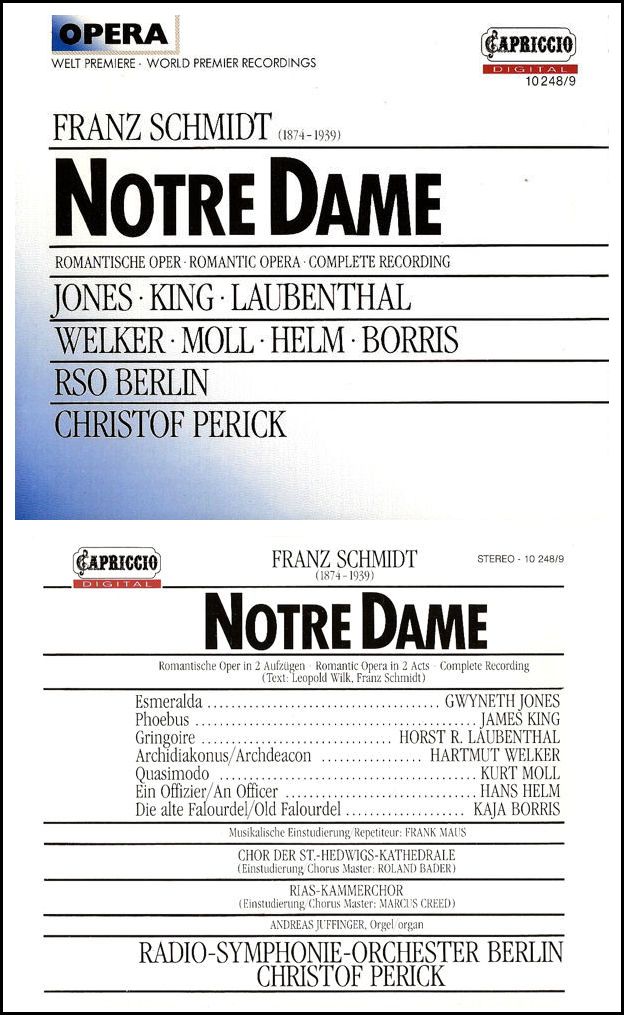

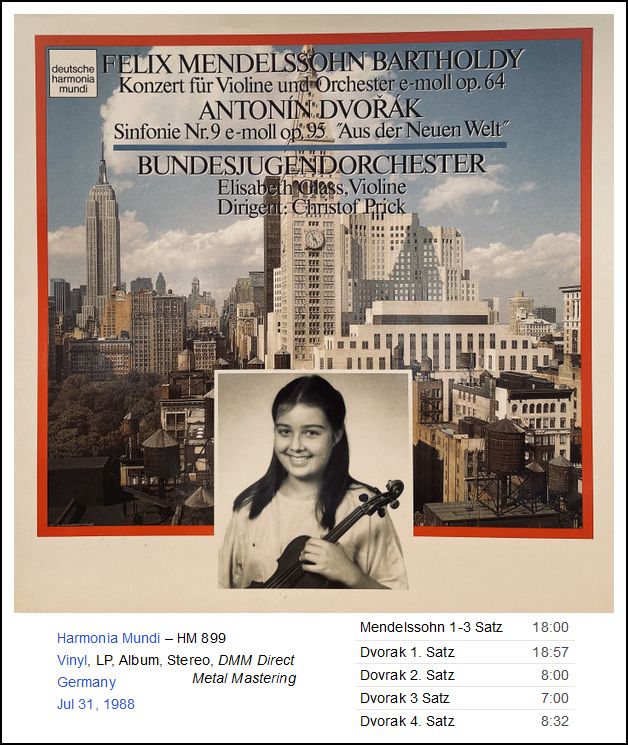

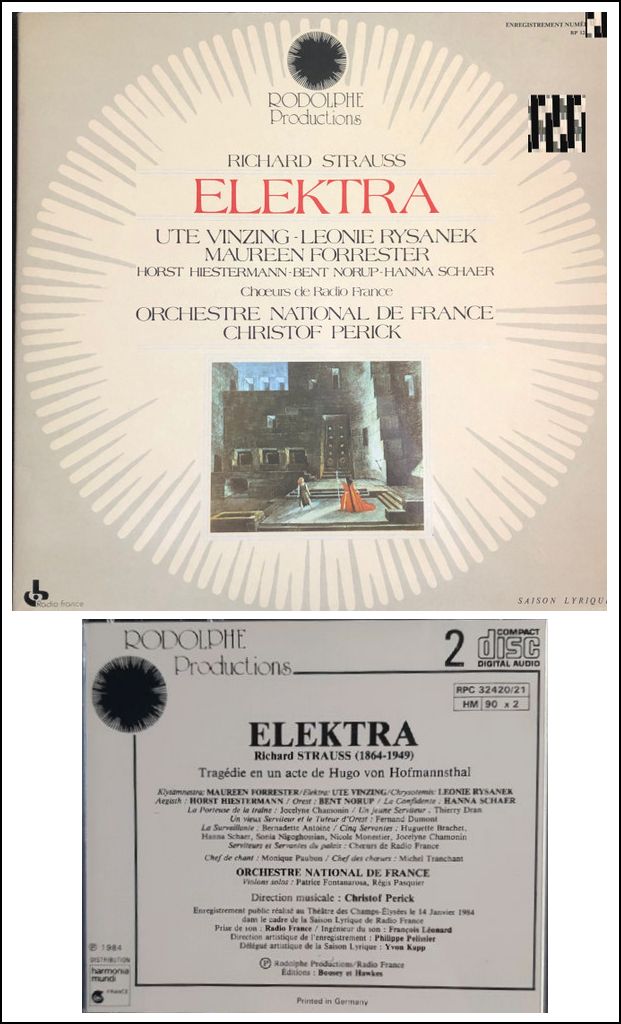

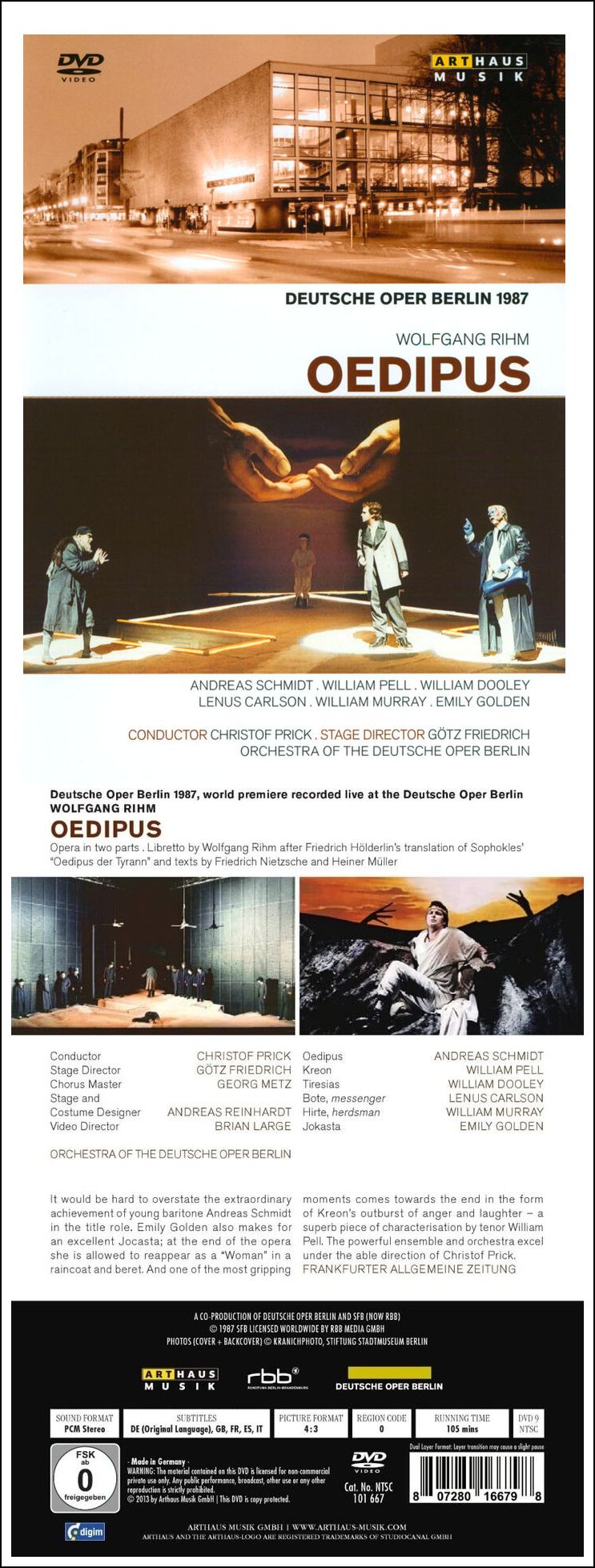

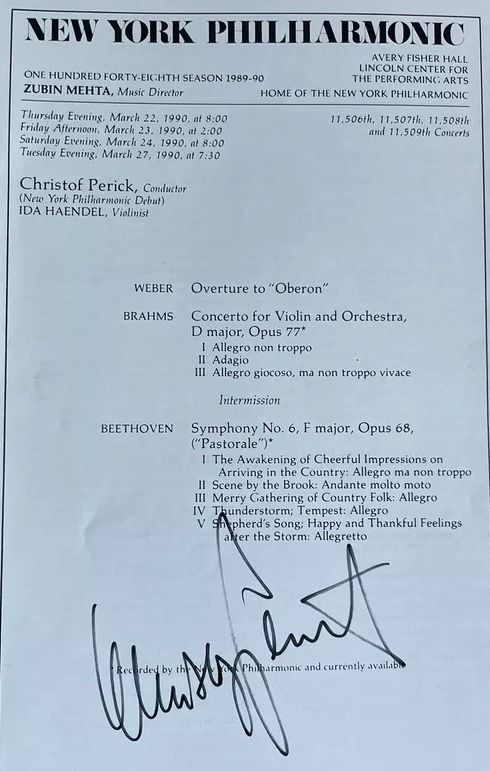

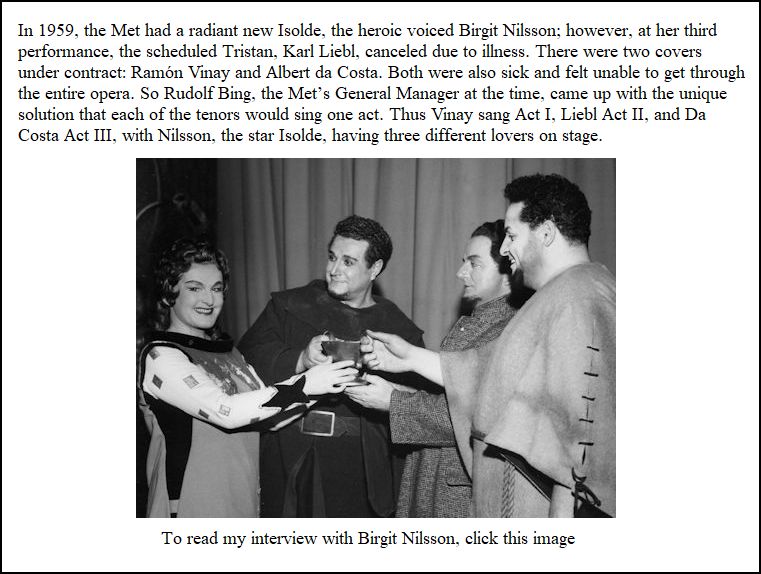

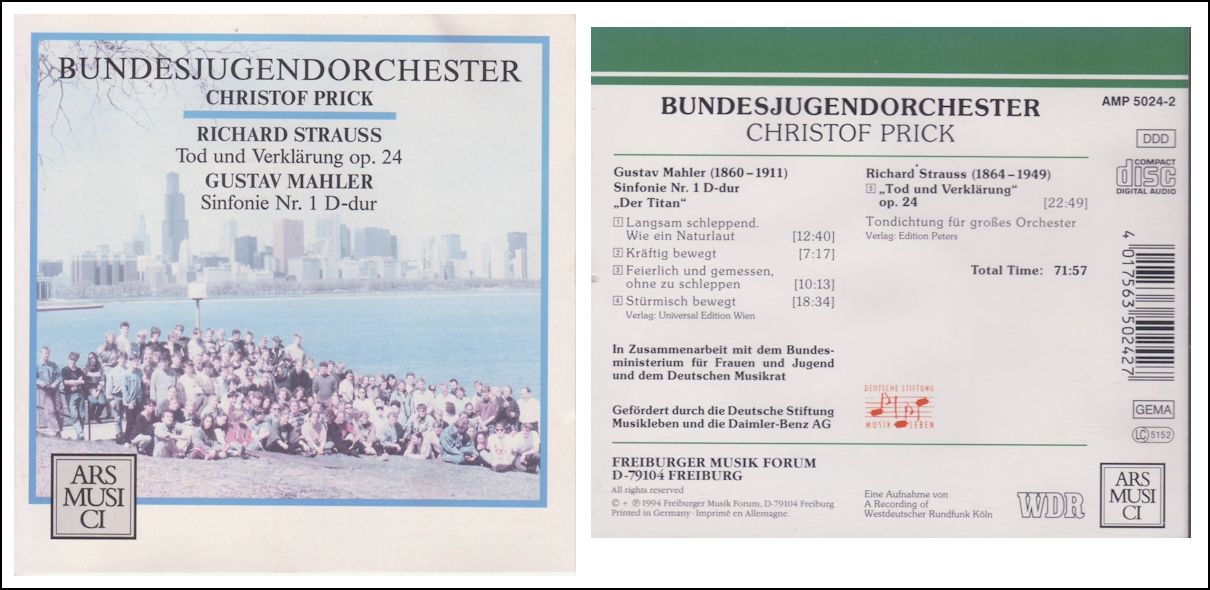

Germany from 1974-77. In recent seasons, Mr. Perick’s engagements have included productions with the Dresden Semper Oper and the Hamburg Staatsoper, and engagements in North America with the New York Philharmonic, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Washington’s National Symphony and the Symphonies of Boston, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Houston, Dallas, Indianapolis, Atlanta, Detroit, Seattle, Milwaukee, Phoenix, San Antonio, San Diego, Montreal and Toronto; summer Festivals that include the Mostly Mozart Festival at New York’s Lincoln Center and the Grant Park Music Festival of Chicago. He conducted the first ever US tour of the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie, Germany’s leading national Youth Orchestra. At New York’s Metropolitan Opera, Christof Perick has conducted productions that include Fidelio, Tannhauser, Die Frau ohne Schatten, Hansel und Gretel and Die Meistersinger. He also has led productions including Der fliegende Hollaender and Parsifal with the Lyric Opera of Chicago; and he conducted the San Francisco Opera in a production of Der fliegende Hollaender. Mr. Perick also conducted the Los Angeles Music Center productions of Cosi fan tutte and Ariadne auf Naxos and the San Diego Opera’s productions of Fidelio, Magic Flute and recently Der Rosenkavalier. Abroad, recent new productions at Dresden include Puccini’s Il triticale, Weber’s Freischütz, Strauss’ Die schweigsame Frau, Salome, Capriccio, Parsifal, Tristan und Isolde, and Fidelio; a ring cycle at Hannover, and concerts with the Orchestre National de France and the Orchestre National de Lyon. Future and recent-past engagements include returns to the Cincinnati Symphony, the San Diego Symphony and the Charlotte Symphony, plus conducting productions at the Cincinnati Opera (Rosenkavalier and Der Fliegende Hollaender), Britten’s War Requiem at the Crane School of Music, SUNY Potsdam, the Chamber Orchestra of the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University, and the Chautauqua Symphony. Christof Perick became a regular guest on the podium of Staatsoper Hamburg as well as Volksoper Wien. == Biography from Kaylor Management Inc.

|

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 23, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1996. This transcription was made at the end of 2024, and posted on this website at the beginning of 2025.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.