|

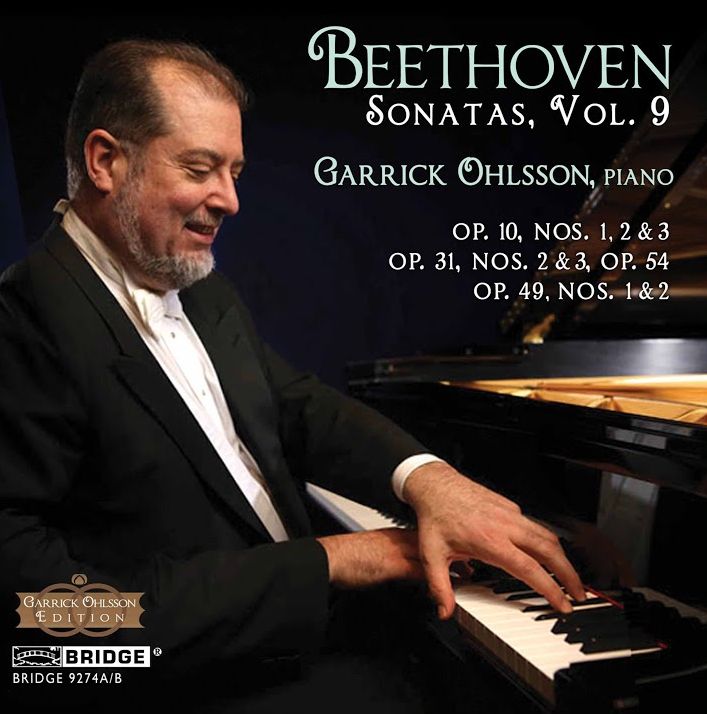

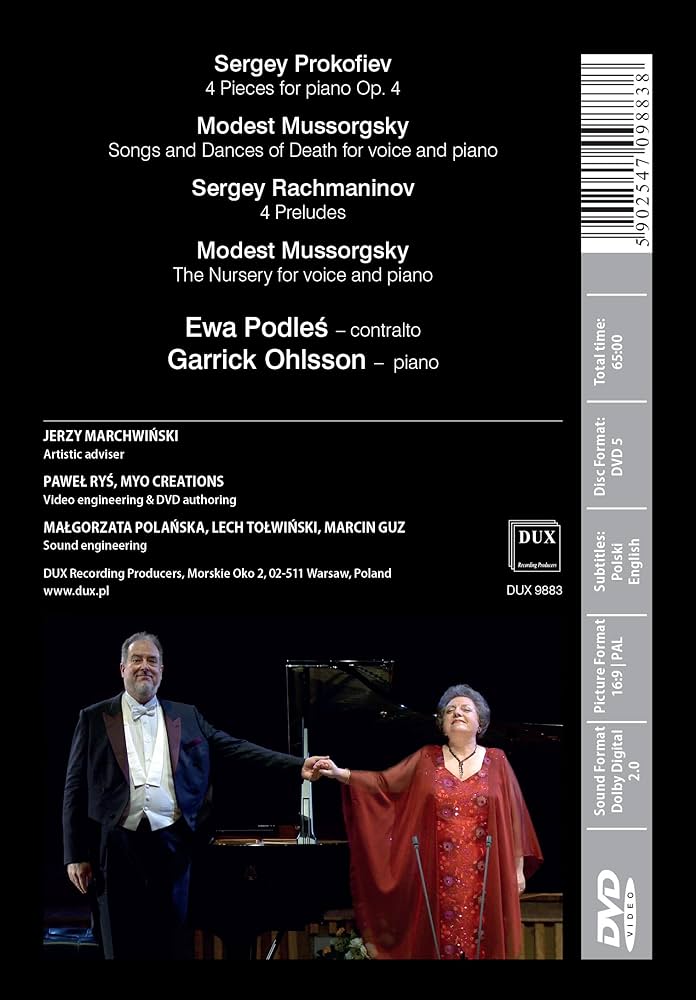

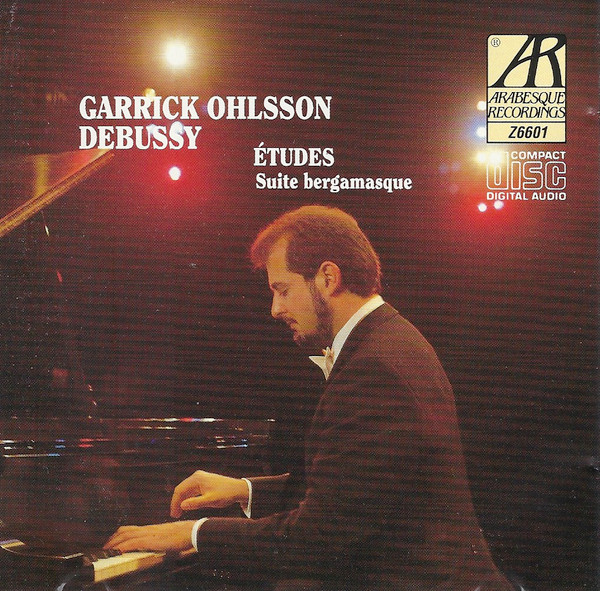

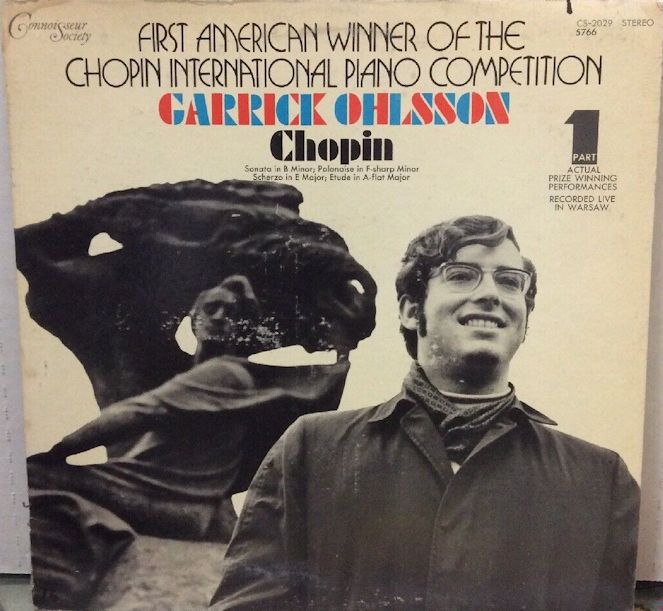

Garrick Olaf Ohlsson (born April 3, 1948) is an American classical pianist. In 1970 Ohlsson became the first, and remains the only, competitor from the United States to win the gold medal awarded by the International Chopin Piano Competition, at the VIII competition. He also won first prize at the Busoni Competition in Bolzano, Italy and the Montreal Piano Competition in Canada. He was awarded the Avery Fisher Prize in 1994 and received the 1998 University Musical Society Distinguished Artist Award in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Ohlsson has also been nominated for three Grammy Awards, winning one in 2008. In 2018, in Warsaw, Ohlsson received the Gloria Artis Medal for Merit to Culture, conferred by the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. Born in Bronxville, New York, the only child of a Swedish father, Alvar Ohlsson, who emigrated from Sweden after World War II, and Sicilian-American mother, Paulyne (Rosta), born in New York City, Ohlsson grew up in White Plains, New York. He began formal piano lessons at the Westchester Conservatory of Music with Tom Lishman at age eight. At the age of 13 he began studying with Sascha Gorodnitzki at the Juilliard School, and later with Rosina Lhévinne. His musical development has been influenced in completely different ways by a succession of distinguished teachers, most notably Claudio Arrau, Olga Barabini and Irma Wolpe. Although Ohlsson is especially noted for his performances of the works of Chopin, Mozart, Beethoven, Liszt and Schubert, his range of repertoire is broad, extending from Bach and Busoni to Copland, Griffes, Debussy, Scriabin, Gershwin, Rachmaninoff, and contemporary composers who have written new works for him. His repertoire includes no fewer than 80 concertos. He is also known for his exceptional keyboard stretch (a 12th in the left hand and an 11th in the right). Ohlsson has performed in North America with symphony orchestras of Atlanta, Charlotte, Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Boston, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, Houston, Detroit, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, Seattle, Denver, Washington, D.C., and Berkeley, among others, at the National Arts Center, with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and with the London Philharmonic at Lincoln Center in New York. He has also accompanied violinist Hilary Hahn and contralto Ewa Podles [as shown in the DVD below-right.]. Ohlsson is an avid chamber musician, having collaborated with the Cleveland, Emerson, Takács and Tokyo string quartets, in addition to other ensembles. In 2005–2006, he toured with the Takács Quartet [shown below]. He is also a founding member of San Francisco's FOG Trio, together with violinist Jorja Fleezanis and cellist Michael Grebanier.

== Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Evanston, Illinois on August 15, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three weeks later, and again in 1989, 1993, and 1998. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.