Composer / Pianist Lionel Nowak

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

At the end of July of 1987, I made contact with Lionel Nowak, and

he graciously permitted me to call him on the telephone for an interview.

Portions were used (along with recordings) three times on WNIB, Classical

97, and now (mid-2024) I am pleased to present the entire encounter on

this webpage.

As I was adjusting the equipment to make the recording of our conversation,

I asked about his teaching of composition . . . . .

Lionel Nowak: I haven’t taught composition in

twenty years. I am essentially a piano teacher.

Bruce Duffie: But you have taught composition?

Nowak: I have taught composition, and several

of my students are around the country doing well.

BD: I always like to ask people who have taught

composition whether it is something that can be taught, or if it must be

innate within each young student.

Nowak: The reason I stopped teaching twenty years

ago was that I said to myself, I can’t teach it unless there is a personal

energy and thrust to want to do it. Just to have control of certain

techniques doesn’t really allow a personal statement to be involved.

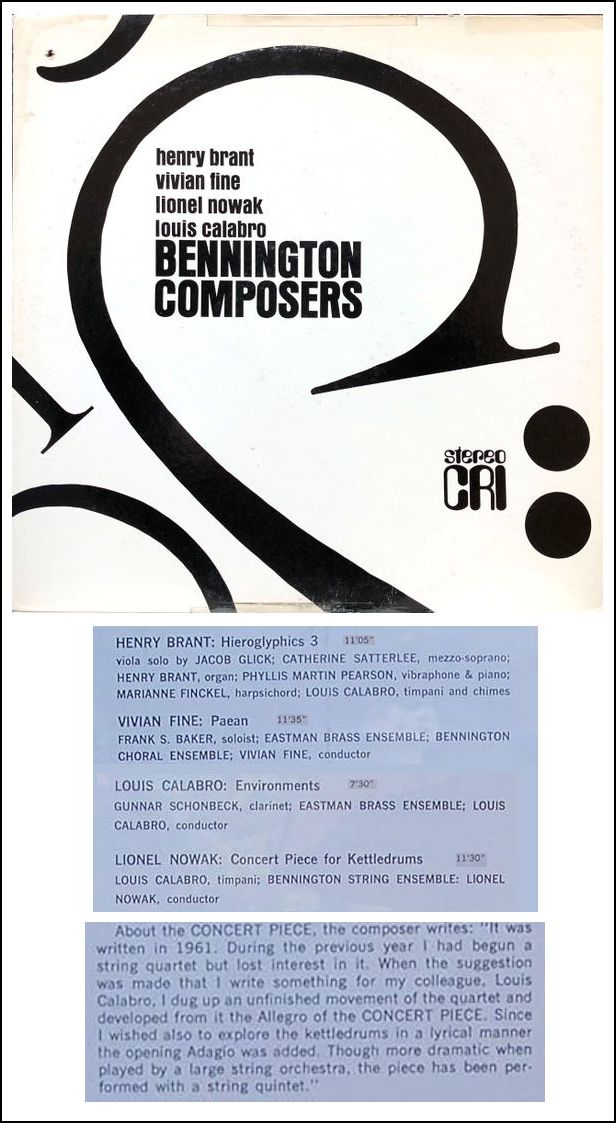

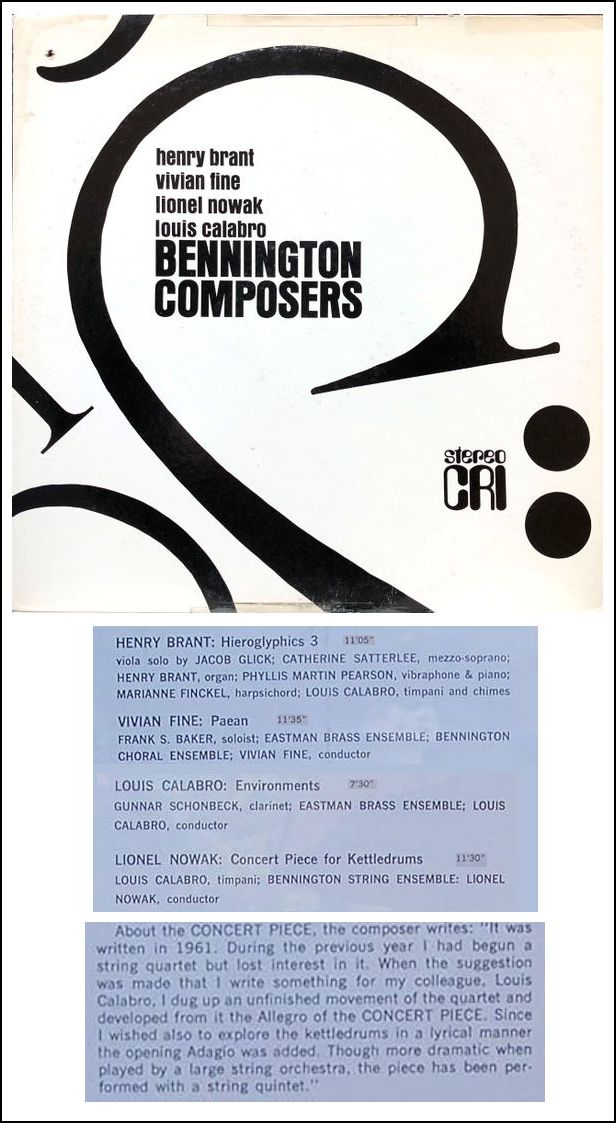

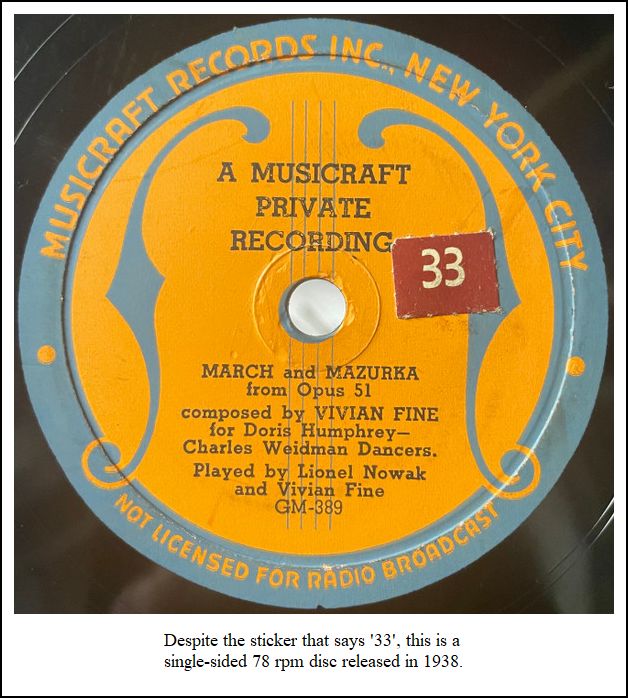

BD: How much should be the techniques, and how

much should be inspiration? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown

at right, see my interviews with Henry Brant, and Vivian Fine.]

Nowak: I can tell you one thing, there must be

a certain talent, and also experience. This also relates to one reason

I took the position here at Bennington almost forty years ago. As

soon as a student enters their first year of college, we allow them to

begin studying music, and they are very interested. In that first

year, they have to compose, whether they’ve ever seen any notes or not.

As they begin to worry themselves about the process, they begin to

have questions about things like harmony and counterpoint. That means

that in their third or fourth year, they may study those courses tutorially.

In other words, all the things that are used in a conservatory as a foundation

for composing, we think should be what the composer finally discovers

he ought to know more about while he’s getting to discover his own sense

of communication.

BD: Are they told to compose, say, a string quartet,

or just compose a piece?

Nowak: It all starts on a primitive level. The

first classes are usually to compose something for a single instrument.

Then maybe the next assignment is for two instruments, and it would

go up the ladder like that.

BD: Each piece would be getting more and more

complicated?

Nowak: Yes, because the means are more complicated,

and more questions arise. During this they discover that what they

had thought was something esoteric is really a matter of being acquainted

with sounds, and deciding what it would be like to shape these into some

sort of a communicative state.

BD: Do you feel that this is a good way to jump

into music, no matter whether you’re going to be a composer or not?

Nowak: Yes, because the composition problems

help them see that in their performance. There is more just set

before them. There are some matters of understanding what is important,

and, having done it themselves, they begin to take a little more interest

in the shaping what they see as notation.

BD: You’ve been observing this for nearly forty

years. Do you feel that the young students coming along have a better

flare for this today than before?

Nowak: On the whole, though the music scene has

been developing more to the personal view of things, rather than to the

traditional assumptions, I think that is one of the good things about

the musical society right now. People who would never have thought

to put notes on paper are suddenly becoming willing to get them down

for some of their friends. Making music is more of an interpersonal

thing than some abstract art in which somebody’s a composer and somebody

else is the performer. We’re trying to suggest that music is a language,

like the English language, and we all can make statements because we want

to say something to somebody. Just as we can do it with words, we

can also learn to do it with sounds if we’re given that opportunity.

BD: It’s

a very admirable way of training youngsters.

Nowak: [Chuckles] Well, we thought so, and

of course, during the 1960s, we worked on the idea in concert with quite

a number of elementary and high school teachers around the country.

We developed what became known as the Manhattan New Music Project, which

had been sponsored by the Office of Education in Washington. We worked

under their funding for six or seven years. The central point was

that the students in the music classes learned how to compose at the first

instance.

BD: Is there any chance that we are getting perhaps

too many composers coming along today?

Nowak: I must say the nature of a competitive society

makes quite a complication for those who would like to think that it

is their business. I don’t know that there are too many composers,

because it’s not a matter of just saying, “I’m a

composer, and I’m going to get acclaimed.”

It’s a matter of music composition for the audiences to decide.

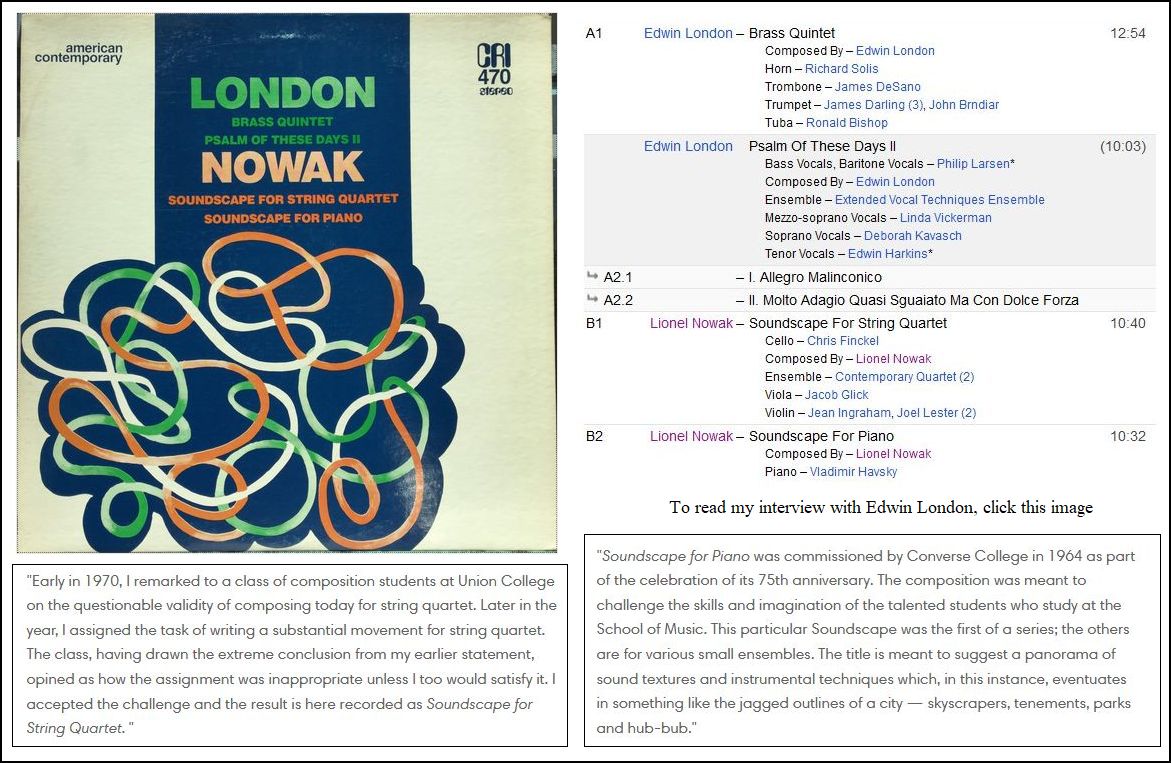

In the 1960s, Henry Brant and I were part of a discussion which was published

in the journal of the American Composers Alliance. We spoke of music

being straight out of Main Street. In other words, music that is

highly publicized, but made so that people can share it with the school

children in their district, and also for the churches which they attend.

Our aim was to make music a natural side of life, rather than letting it

become a special kind of thing.

BD: Then let me ask a great big philosophical.

What is the ultimate purpose of music in society?

Nowak: [Thinks a moment] It gives the person

a further way of discovering who he is, and how he would like to communicate

with people around him.

* * *

* *

BD: I want to go back to some of your early years,

and ask you what you learned specifically from Quincy Porter.

Nowak: Well, let’s see... that’s about sixty

years ago.

BD: Was he a good teacher?

Nowak: I think he was a good teacher, but I don’t

think he was the kind of a teacher that Roger Sessions or Arnold Schoenberg

would have been. At that time I wasn’t particularly interested in

anything like composition. I didn’t take the whole operation as seriously

as I might have.

BD: At that time you were more into the piano?

Nowak: I was really just practicing the piano,

yes!

BD: Are you a better composer because you are also a

first-rate pianist?

Nowak: I don’t know that those necessarily go together.

It’s very important that a composer has some performance skills so he

understands the nature of performing, and how to make a statement for an

audience. But otherwise, I don’t necessarily think there’s a connection,

except if a performer keeps his performance alive, and has so a chance to

play with other people, he becomes acquainted with the timbre and the textures

of instruments. To that extent, being a performer is useful in composition.

BD: Then let me turn the question around. Did

your performing improve because you were also actively involved in composing?

Nowak: I can answer that more clearly and positively.

I tried to manage greater insight in the things that I was playing.

It suddenly become apparent to me that as I was playing the music

of colleagues and friends and contemporary musicians, when I would go back

to playing Schubert and Mozart and Beethoven, I discovered I could take

comfort in the fact that I had studied them when I was a pianist.

BD: When you were writing a piece of music, how

did you know when you had finished? How did you know when you should

put the pen down and say it was done?

Nowak: [Laughs] This is one of the difficult

things to do, particularly when there are no standard forms! This

is part of the decision of the whole of each moment that happens. As

in life, other events come into play. At any given moment, you’re

making decisions, and finally you say that this is the final decision.

You’ve been searching to see all the possibilities, and today you’re

going to sign something. To some extent, what can be an important

part of this whole process is to have a performance, so I have to make

sure I’ve something ready to be performed. I’ve said what I’ve had

to say, and I’ve realized the material so that I haven’t lost my way. But

this is just an observation I make. I don’t think you can measure

it.

BD: Do you ever go back and revise the scores

after you’ve had them played or published?

Nowak: I make small revisions, but nothing really

basic. I might change some of the details in the relationships

of some of the instruments, or change pitch level, or maybe make a few

rhythmic changes here and there, but nothing substantial.

BD: Have you basically been pleased with the performances

you have heard of your music over the years?

Nowak: I haven’t heard them all, but the ones

I’ve heard I’m generally pleased. Since so much of the performance

of my music takes place at the college where I know my colleagues, they’re

first-rate musicians, and I have every reason to be satisfied with them.

BD: Are you ever surprised by their interpretation?

Nowak: There are moments when I hear something that

I hadn’t realized the possibility of in a certain piece, and that is

often very exciting. It’s necessary to have a piece played by

different people. That way you become aware that what is on the

paper is very static, and unless it is brought into motion you could

lose part of the basic intent of the piece. The motion which is

brought into the work, and the balances you put into the score are somehow

understood by the player, and those present new moments you hadn’t realized

were there. I enjoy hearing my music played by people, so a lot

of my things are played by my students as well as my colleagues. Student

performances are very imaginative. They may not always be professionally

exact, but from the point of view of musicality, young people have insights

which they should have an opportunity to explore.

BD: It sounds like composing is fun.

Nowak: Well, it’s fun! Sometimes it becomes

very trying when things get a little complex. The decision-making

process becomes more complicated, and that presents moments of frustration.

Then, tomorrow is a fresh day, and it will bring some new concerns

in your mind.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

Nowak: That all depends on what you mean by music!

[Both laugh] I’m sure the structures of sound will always be important

and also exciting to people, but if you mean as music as a business, this

will always have its ups and downs. That part of music has hardly

ever attracted me at all.

BD: Is there too much business creeping into

music?

Nowak: Whatever has been creeping into it has been there

for a long time. I’m sure there was a lot of business in the past,

even during the time of Mozart and Salieri. But to the extent that

music has become a kind of commodity, we’ve lost the broad view that music

is a universal kind of language. It is a special usage of sound,

and that’s why it’s been important to all cultures, so that we see what

we call music is a small incident of a large musical world.

BD: What is next on the calendar for Lionel Nowak?

Nowak: I can never answer that. If I review

my past, it looks like my composing goes in fits and starts. When

I was active as a touring pianist, composing had really taken a secondary

part in my life. Then in the last forty years, I dedicated myself

to teaching. The music energies and the musical imagination has turned

so much to teaching that most times composing falls by the wayside. I

learned that when I wouldn’t be able to meet a deadline, that’s okay.

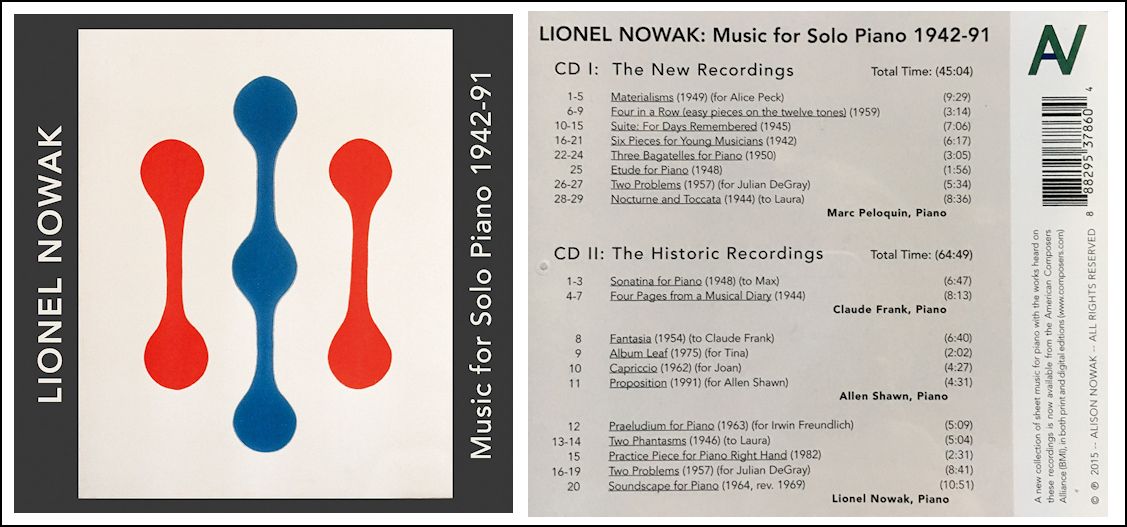

When the time comes, I’ll get something done. At the moment I’m trying

to complete a piano piece. I haven’t written a piano piece in a long

time. I wrote one in 1981 and one in 1974, and those are the only

piano pieces I’ve written in the past ten or fifteen years.

BD: [Being on radio, I asked him how he preferred

his name to be pronounced, and he said Noh-vahk.] I certainly

appreciate your spending the time with me this evening. I know it’s

been an effort, and I feel I’ve learned a lot about you and your ideas.

I look forward to being able to put your music and thoughts on the station

and a number of times. [As noted at the top, and specified at the

bottom of this page, I did programs in 1989, 1991, and 1996.]

Nowak: I appreciate it very much. Thank you.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on July 25, 1987.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, and again

in

1991 and 1996. This transcription

was made in 2024, and posted on

this website at that time. My

thanks to British soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these interviews

for print, as well as a few other interesting

observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie

was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until its final moment

as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since

1980, and he now continues his broadcast series

on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited

to visit his website

for more information

about his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also like to

call your attention to the photos and

information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than

a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.