A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Bruce Duffie: What do you expect of the audience that comes to hear the music of Vaclav Nelhybel?

Vaclav Nelhybel: Really, the bottom line is I don’t know. What is audience? Let’s put it this way – I don’t think of the audience while composing.

BD: Then for whom do you write?

VN: Those answers are all kind of big labels. In my case, composing is the thing I like the most to do, and – I am not improvising this answer – to compose music is the best means to manifest my existence as human being. I feel that is my function as a person, and if something excites me, it is much more complex. I must talk in specifics. For example, I am delivering today a commissioned work I started working on one and a half years ago, but I will be working now on something that will be performed in about two and a half years, a concerto for organ and orchestra. I am in this kind of vacuum a little bit; ideas come in because I am not under pressure. I do function as a composer and as a person; the person and the composer is somehow identical. I never said it, I never thought it, but that’s how it is. So, for whom am I composing? Again, those words sound so big and so fantastic. I am trying to share my experiences, etc. Finally, that’s what it is! If something excites me, I try to freeze it into paper, to have it there.

BD: It’s interesting that you would say you’d “freeze

it” onto paper, because then the sound isn’t frozen,

it’s a living thing.

BD: It’s interesting that you would say you’d “freeze

it” onto paper, because then the sound isn’t frozen,

it’s a living thing.

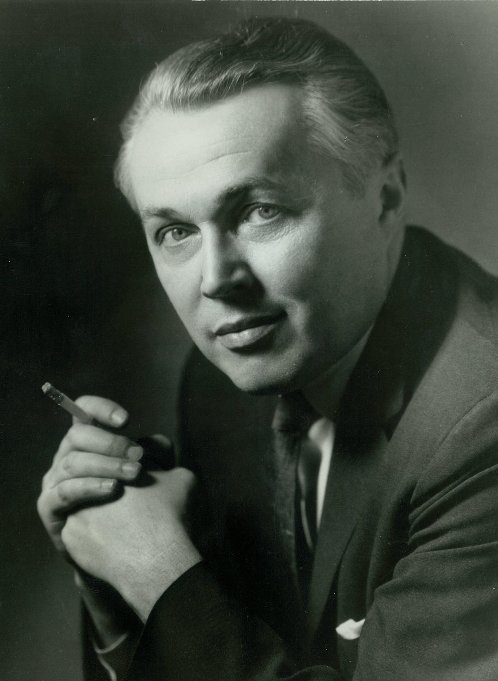

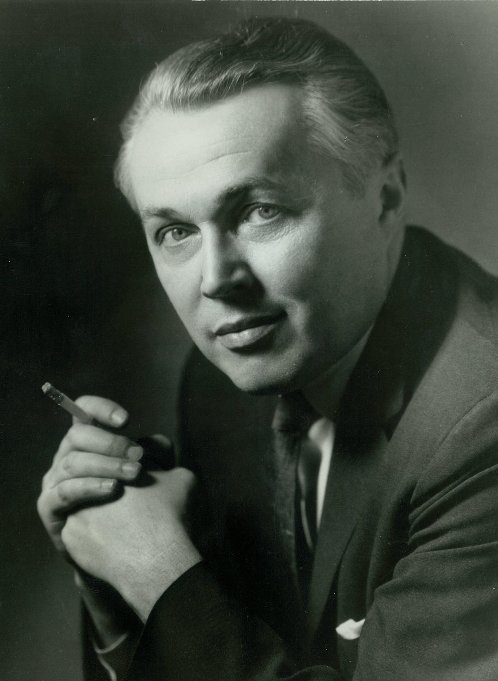

[Photo at left and

the next where he is conducting show Nelhybel with the Fifth U.S. Army Band

in the mid-1960s]

VN: But I don’t think

so. We can say [sings a musical passage quickly]; do you know how long

it takes to write [sings the same passage very slowly]? This is something

that floats very fast, and it’s funny that when you compose it, it’s in slow

motion. I have two pianos at home, but I never touch the instrument.

I compose in total silence; I don’t sing for myself. Of course, when

I was eighteen, nineteen, twenty, the piano used to be my best friend, my

best helper. But then, having conducted for twenty five years in

BD: In composing, where is the balance between inspiration and technique?

VN: Who knows? Period. There will be very few answers. I may have some strong opinions, but then I will laugh because how does one get an idea? What is inspiration? Would you say the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is a really inspired composition? There was a manuscript sketchbook of Beethoven’s Fifth – about twelve or thirteen pages – and during the Second World War they put it underground. I saw it! There were pages of sketches until finally the theme was [sings the opening theme]. For pages he had written [sings different ideas similar to the familiar opening] until finally he had it with all the drama in it. That’s inspiration. How much sweat and blood there was, changing and correcting it. I am saying Beethoven knew – because he was a great composer – that there was gold in this little theme, and he was working on it and working on it. For years I wanted to save every little piece of paper I sketched on, and then show a commissioner my suitcase full of ideas and the enormous pile of sketches. But there must be some definitive idea in a composer. Beethoven worked until he got it – resting on the strong beat and entering on the weak beat; there’s so much drama in it! To some degree, everybody probably has some sort of idea in them. Young composers, when they grow older and then look back at the composition they composed a decade ago, will say, “How did I let this go? This composition is awful!” That is because the youngsters were very anxious, very hurried, and had no time.

BD: Now that you’re a mature composer, do you feel that works you wrote ten, fifteen, twenty, thirty years ago are of lesser quality?

VN: No. I was

very fortunate to have one man who had an enormous influence on me.

A choral man, he taught conducting technique – not conducting, but conducting

technique. He was probably the best choral conductor in

BD: Do you not feel that you have a responsibility to the music?

VN: I don’t feel it; it’s there! It’s my life, and this is what I fill my life with! So would I cheat on it? Heck no!

BD: You can work on a composition as long as you want, so how do you know when each one is finished?

VN: That is the most awful thing. As long as the “inspiration” starts running, I write it as fast as I can. Then I start working on it, and comes the devil’s advocate. I get started and go on and on, and then get stuck, and you feel what there should be but it doesn’t come. Then when it finally comes, it can be fast, it might be moderately fast, it can be very slow. Finally the composition is finished, and then I put it away. I’m not involved right away in composing a new piece; I can’t be! But there is much to do. I do proof reading, I clean up orchestration; whatever it is where there is no involvement creatively directly. Then I go back, and of course I’m cool by now. The heat of the creativeness is gone and I am now the devil’s advocate; I am the critic. Fortunately we have copying machines now, so I make always three copies and very often I need a fourth. I make changes, sometimes complete changes, working with three different colors - green, blue, and red. Then I have a list on which I state, “So-and-so: see also sixty measures later, where it’s changed and shouldn’t be the same.” Then comes really slaving on it. Finally you have a feeling that it’s it! It’s polished, it’s exactly what I want. But then you say, “No, it’s not yet! Go back!” It’s an addiction, a terrible addiction. Sometimes when it’sVN: Well, yes.

BD: How do you decide which pieces you will do and which pieces you will not do?

VN: The past one and

a half years was my orchestral period. I had one commission from

BD: Are you basically pleased with the performances you hear of your music?

VN: There’s no answer, basically. You have the whole scale, from suicidal to elated. I still have an opinion about it... There are certain things that I expect to happen, of course. The conductor has absorbed my composition and identified himself with it, even though his metabolism was different than mine.

BD: Do you expect interpreters to work with your music?

VN: Oh, I like it! When they ask, “How should we do it?” I say, “I don’t know!” I don’t like metronomic markings, because if you have sixteenth notes and you take it so fast that it is only mumbled, then of course you need to do it slower.

BD: Are you pleased with the recordings that have been made

of your music?

BD: Are you pleased with the recordings that have been made

of your music?

[Photo at

right taken during recording sessions with the Fifth U.S. Army Band]

VN:

I have two answers. One answer is a personal one, and is quite

often, yes. If you ask why, I will say I like a particular recording

because it has a touch of personality. If it sounds very “this is how Nelhybel

would do it”, God forbid! I am a different animal than you are!

If you are a squirrel, try to be the best squirrel there is, not an elephant,

and vice-versa. I do like it if somebody identified themselves with

the piece and made it his own. The important thing to me is that there

is the life in it, there is drama in it. My second answer is that today

the very important criterion is sheer perfection. If somebody cracks

a wrong note, it should not be so important as long as the tension and the

smoothness of the piece was there.

BD: Do concerts work well on television? Have you seen them, and do you think they’re a good thing?

VN: To me, a live performance is a live performance, period.

* * *

* *

BD: Your compositions are in a very tonal idiom, which is

very unusual today.

VN: I would not call me tonal what-so-ever. I am not a tonal composer ever, never have been. When you say tonal, I think dominant, sub-dominant, etc. God forbid! I have a few favorite composers including Machaut, Monteverdi and Bach. Monteverdi is one of my passionate loves and a passionate hate, because Monteverdi was the no-good guy who introduced tonic, sub-dominant. The Germans jumped on that, and what is tonic remains forever. But if you play a major triad or a minor triad, you can hear dissonance in it. The subdominant means to relax. Then comes the guy who says get up – the dominant – and go to the tonic. My music I call panchromatic; I use all twelve notes. For instance, in my Symphonic Requiem, in the first one and a half minutes all twelve notes are constantly hanging somewhere all over the range. It ends in F, and even though all twelve notes are in it, you still know it’s in F. You can have clusters and orchestrate it in such a way that you stop it, but when three people play a certain chord, you have the feeling, “Oh yes, this was it.” What my music has is gravitational pull. I participated once in something done by CBS or 20th Century Fox or some group like that, on background music for films and such. There were twenty people – truck drivers, lawyers, boxers, anybody – and we played Story of a Soldier. It meant different things to different people.

BD: Have you ever gotten involved in electronics?

VN: No.

BD: Why?

VN: I have absolutely nothing against it. I have no philosophies about orchestras dying out and what-not because when I came here, I was so fascinated with this country, I was on the moon in a totally different world. Twice I was invited to participate in a synthesizer event where I’d be given one and my name would be placed on it. I said no.

BD: Where is music going today?

VN: Who am I to know???

[Ponders a moment] Well, yes, I do have an answer. After the

Second World War, Germany,

BD: Is rock-and-roll

music?

VN: I don’t know; I

don’t know what music is because it is used for so many things. One

time we were adding an addition onto our house, and we had the radio on for

about eight hours a day. Unbelievable what I heard! I discovered

one piece of rock-and-roll that had virtual elements of Monteverdi in it.

I know what rock and roll is because I have two kids, almost sixteen and

eighteen years, [laughs] and their musical tastes are awful! My daughter

is a brilliant classical musician, but she’s two different people.

She’s very intense with the rock and roll, but also plays in an orchestra.

*

* * *

*

BD: I understand you wrote an opera early in your career?

VN: It was ballet with

singers in it, and also dancers. It’s called The Cock and the Hangman, and it’s based

on Slavic folklore. There are different types of characters

– those who are human, those who are more than human, and those

who are less than human. Those who are human sing; those more than human

and less than human dance. It was done in the National Theater in

BD: Do you feel you are part of a lineage of composers?

BD: Do you feel you are part of a lineage of composers?

VN: I don’t know; I

don’t think so. I am not a Czech composer – I am modal. My tale

is squeezed in the fourteenth century, or even earlier. I am fascinated

by the Middle Ages. I am not a tonal composer like Smetana or Dvořák.

I was born about twenty five kilometers from Janáček, where people

there talk funny, very shortly, have funny accents, and so and so.

My only closeness to any Czech composer would have to be Janáček,

but not necessarily that my music sounds like his. Janáček created

his own modality and certain things. I am a more Slavic composer, more

of an Eastern composer, more of a Russian composer. People ask if there

is a composer who was my greatest influence, and I reply nobody, not one.

When I discovered music, I would discover one, then throw him away, then

the next, and the next. The Middle Ages is what really got to me; don’t

ask why. As I mentioned before, I love Machaut, Monteverdi, and Bach,

then Stravinsky. It is interesting – everything might have been different

if there had not been the Second World War. I had just come in contact

with Stravinsky about two months before Hitler occupied

BD: Is music ever political?

VN: How can it be? You can use a whole scope of paint colors – is it evil or is it good? No, though, that’s not a very good metaphor. Two people can have very different reactions from a piece of music – one may have a belly ache, the other may say “I love you” for it. You can put any three or five words for a title and it still doesn’t change anything, and after a year you will probably say, “No, I shouldn’t have used this title.” It’s interesting you say “political.” Yes, they can take a political slogan and add music to it, and then it takes on a new dimension. It’s not political per-se, but it can be used for political purposes; it’s manipulated.

BD: Do you expect your music to last?

VN: [Surprised at the question] How do I know? I do not have any of this kind of suicidal or messianic thought. I function, I am here. No, how can I know?

BD: Does it please you, though, to have a piece twenty, thirty, or forty years old still played?

VN: [Sarcastically]

Oh heck no! Why would you ask me such a silly question sir???

[Both laugh] But, of course.

BD: What’s the role of the critic?

VN: I don’t know, I really don’t know. I have had some marvelous experiences with critics and I’ve had some experiences that were not so good. I cannot complain too much. There have been some total misunderstandings, such as when somebody said “This is the Opus Finale of Nelhybel.” The critic wrote that I didn’t show anything of my technical skills. Well, this was a piece for junior high school. When I write on the school level, I put myself into the strait-jacket and then dance. If you go and run a mile (which I never did in my life), they say there comes a moment when your metabolism starts glowing, and it’s a fantastic feeling. For those little kiddies, the music for them is glowing.

BD: Is the act of composing

fun?

VN: No. I heard somebody say, once, that it’s rather suicidal. I wouldn’t say that. If it were not fun, who would do it???

BD: Is each one of

your pieces then like an offspring?

VN: Yes. I made

it somehow. It’s a chunk of you, yes. Is it fun? What is

fun? To me, as a foreigner, the word fun implies, “Oh lets go and drink

beer.” To me the really beautiful thing is if it produces joy.

Though I have never taken drugs, I know that you can get high and it can

be fun, but it’s not joyful. After joy doesn’t come a complete collapse.

Is it fun to have kids? No, it’s awful! But it’s also the most

wonderful thing there is.

BD: Do performers ever find things in your music that you

didn’t know were there?

VN: Yes, absolutely. I hope it is something that is a plus, not a minus, but what is more important is that he found, somehow, a different soul. It was his soul, and it worked – my soul and his soul. We are different souls, yet they could burn with the same flame somehow, metaphorically speaking.

BD: Do you ever revise your scores?

VN: I’ve done it many times.

BD: Even after they’re

published?

VN: This is rather tricky – just try to do it and you will see what the publisher tells you. In my case, it is really very much a definite form. Somebody might say, “Nelhybel, I didn’t like this section here.” He will say it’s not properly put together – like the thumbs are too big on a small hand – but I will say no, because I take enormous time. One composition could take me two and a half years.

BD: Do you work on just one thing at once, or do you have several things going at the same time?

VN: I have different stages. During the creative stage, I come up with ideas and put them into my folder. As I said, Beethoven knew [sings the first four notes of the Symphony No. 5] was brilliant.

BD: Is that what makes music great, what is done with the small ideas?

VN: I have virtually

no answers – I don’t know. If twenty people heard that, it would mean

twenty different things. Some would be very categorically against it,

and some would say, “Oh yes!”

*

* * *

*

VN: It all depends.

If you work with the university level, it’s quite close to the professional

level. I try to find what produces a certain something in a performance,

to see if I can plan it or manipulate it. In any rehearsal I try to

show them what it means to have a total climax of dynamics. Then when

you hear them do it, it changes to a completely different sound. I

conducted the All City Houston Orchestra – a magnificent

orchestra, one of the best youth orchestras ever – in

a twenty minute piece of mine in

BD: When you set out to write a piece, do you know how long

it’s going to be?

BD: When you set out to write a piece, do you know how long

it’s going to be?

[The photo at left was

taken at the University of Scranton just a few days before the composer's

death]

VN: You know something. Very often they will commission and say, “I want something that is fifteen minutes.” Don’t ask me how you know. I am not describing any kind of method – there is no such thing.

BD: When arranging concerts of your music, is it better to have all contemporary music, or to put your piece among Beethoven, Haydn and Shostakovich?

VN: I do whatever they want for whatever reasons they have, because everybody has their reasons.

BD: Are you the ideal interpreter of your music?

VN: Oh gosh, that’s a funny question. First of all, I am not an interpreter. I don’t know to what degree a conductor is an interpreter!

BD: Do you ever make suggestions to conductors?

VN: No. I try not to, unless they do something very basically wrong, and it’s somebody where I can talk and say it to them. Physically, I don’t go into situations where I would have to do it. I never judge.

BD: Do you ever judge competitions?

VN: No. I did once, and never again.

BD: You find it impossible to look for greatness in music?

VN: What is greatness, what is it?

BD: Is it not something that you strive for?

VN: Who doesn’t? Without exception, we all do. We are all so limited. We see limits, but we all want to surround them and go around it.

BD: You’re not looking for fame?

VN: What is fame?

BD: I suppose most people are thinking about notoriety.

VN: I really don’t

have the answer.

BD: Thank you so much

for speaking with me today. I wish you luck with these upcoming concerts.

| Internationally renowned composer

Vaclav Nelhybel was born on September 24, 1919, in Polanka, Czechoslovakia.

He studied composition and conducting at the Conservatory of Music in Prague

(1938-42) and musicology at Prague University and the University of Fribourg,

Switzerland. After World War II he was affiliated as composer and conductor

with Swiss National Radio and became lecturer at the University of Fribourg.

In 1950 he became the first musical director of Radio Free Europe in Munich,

Germany, a post he held until he immigrated to the United States in 1957.

Thereafter, he made his home in America, becoming an American citizen in

1962. After having lived for many years in New York City, he moved to Ridgefield

and Newtown, Connecticut, and then, in 1994, to the Scranton area in Pennsylvania.

During his long career in the United States he worked as composer, conductor,

teacher, and lecturer throughout the world. At the time of his death on March

22, 1996, he was composer in residence at the University of Scranton. A prolific composer, Nelhybel left a rich body of works, among them concertos, operas, chamber music, and numerous compositions for symphony orchestra, symphonic band, chorus, and smaller ensembles. Over 400 of his works were published during his lifetime, and many of his over 200 unpublished compositions are in the process of being published. (Nelhybel's passion for composing was all encompassing and left him little time for "marketing" his works; for this reason, many of his compositions, though commissioned and performed, remained unpublished.) Although Nelhybel wrote the majority of his works for professional performers, he relished composing original, challenging pieces for student musicians and delighted in making music with young players. Nelhybel was a synthesist and a superb craftsman who amalgamated the musical impulses of his time in his own expression, choosing discriminately from among existing systems and integrating them into his own concepts and methods. The most striking general characteristic of his music is its linear-modal orientation. His concern with the autonomy of melodic line leads to the second, and equally important characteristic, that of movement and pulsation, or rhythm and meter. The interplay between these dual aspects of motion and time, and their coordinated organization, results in the vigorous drive so typical of Nelhybel's music. These elements are complemented in many of his works by the tension generated by accumulations of dissonance, the increasing of textural densities, exploding dynamics, and the massing of multi-hued sonic colors. Though frequently dissonant in texture, Nelhybel's music always gravitates toward tonal centers, which makes it so appealing to performers and listeners alike. Nelhybel received numerous prizes and awards for his compositions, among them, in 1947, a prize at the International Music and Dance Festival in Copenhagen, Denmark, for his Ballet In the Shadow of the Limetree, in 1954, the first prize of the Ravitch Foundation in New York for his opera A Legend, and, in 1978, the "Oscar" of the band world, an award from the Academy of Wind and Percussion Arts. Four American universities honored him with honorary doctoral degrees in music. The many music reference books that have entries about Nelhybel include Alfred's Essential Dictionary of Music, Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, International Who's Who in Music, The Heritage Encyclopedia of Band Music, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Nelhybel's music is performed all over the world, and the list of countries where his works are played is ever growing. -- From the Official Website, maintained

by the University of Scranton

|

This interview was recorded in suburban Chicago on October 25, 1986.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB 1989, 1994, and 1999.

This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2011.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.