|

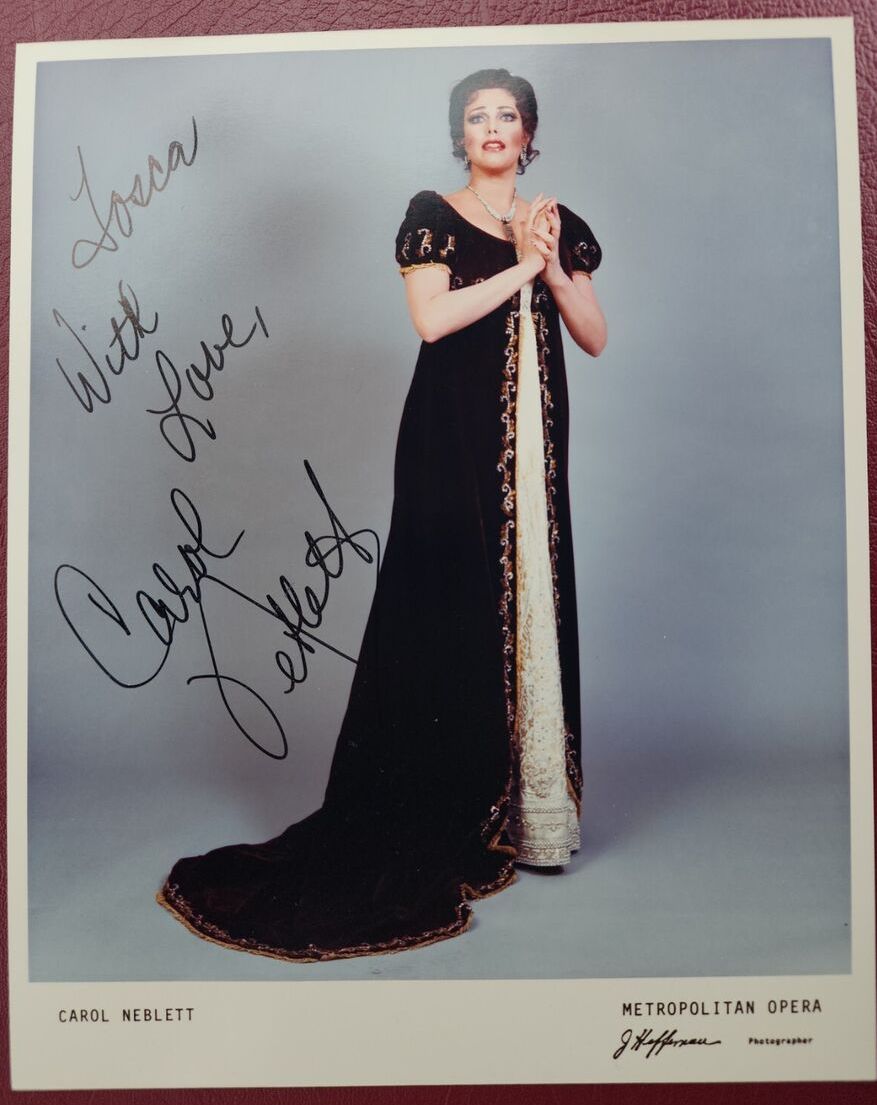

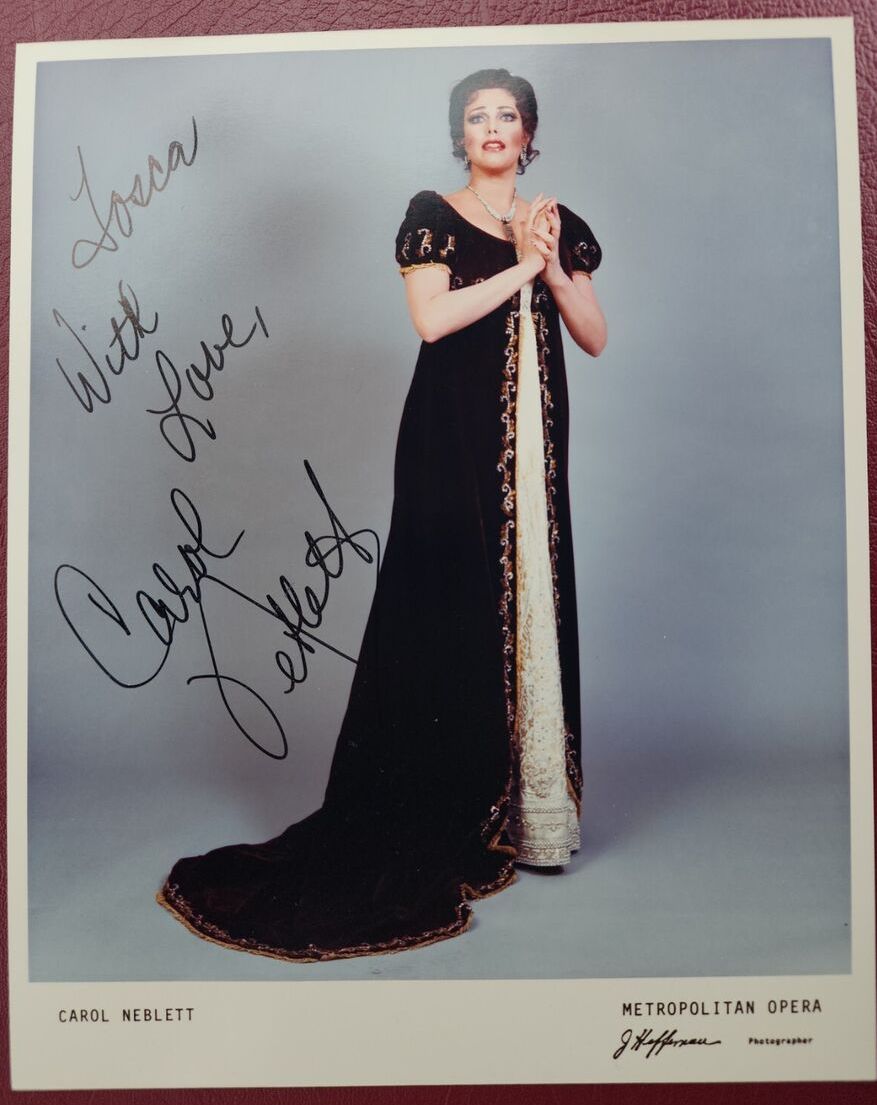

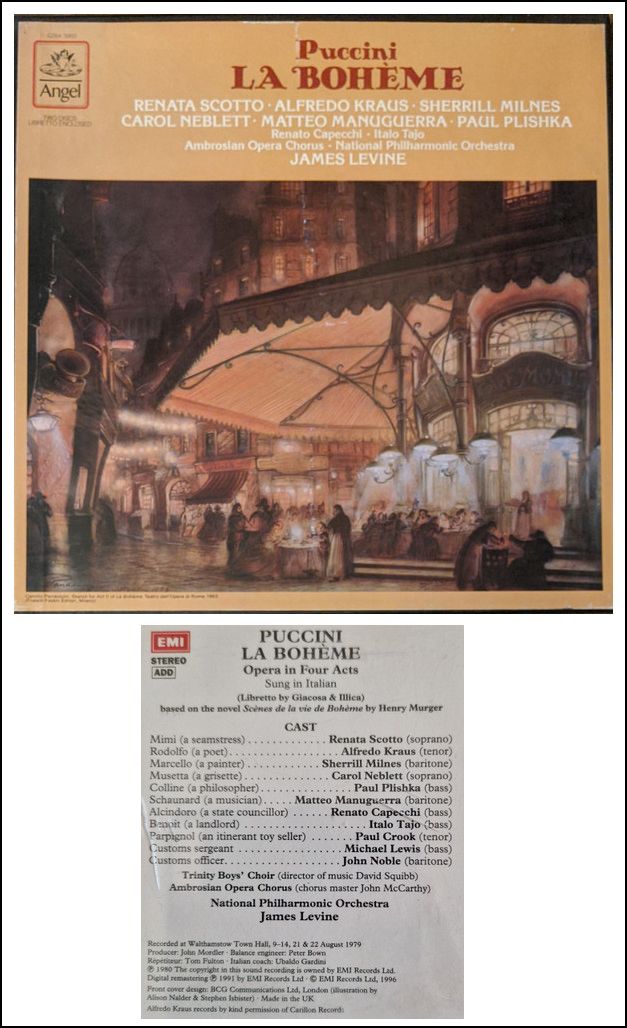

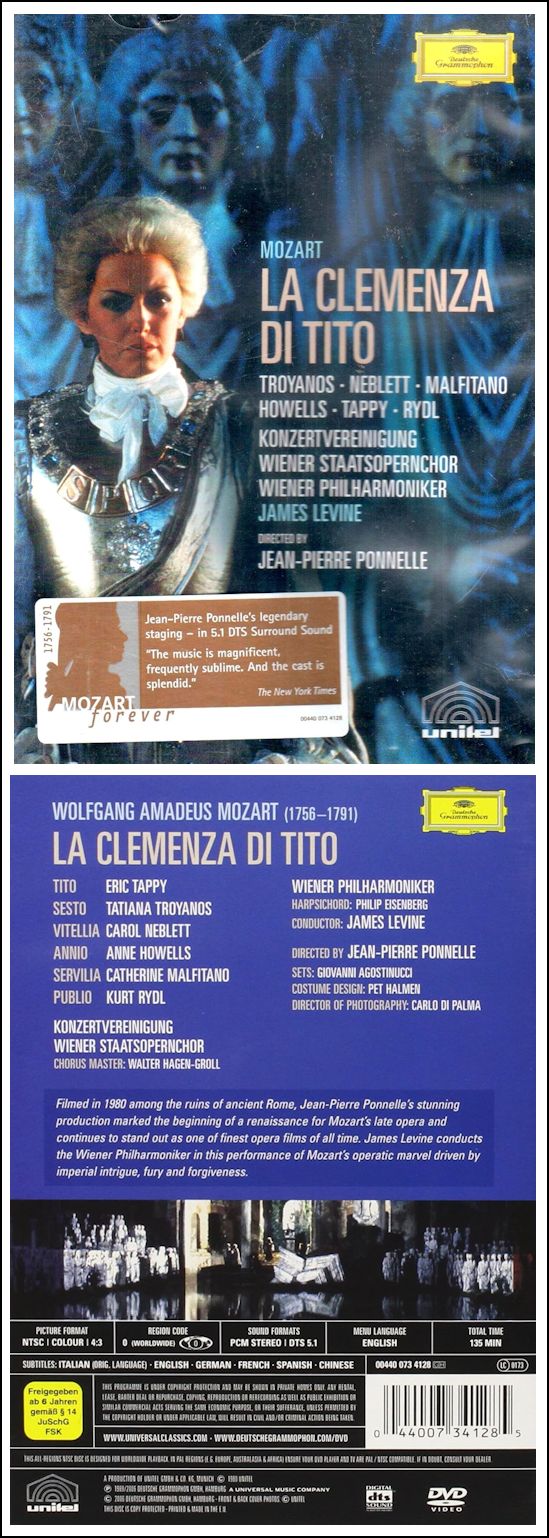

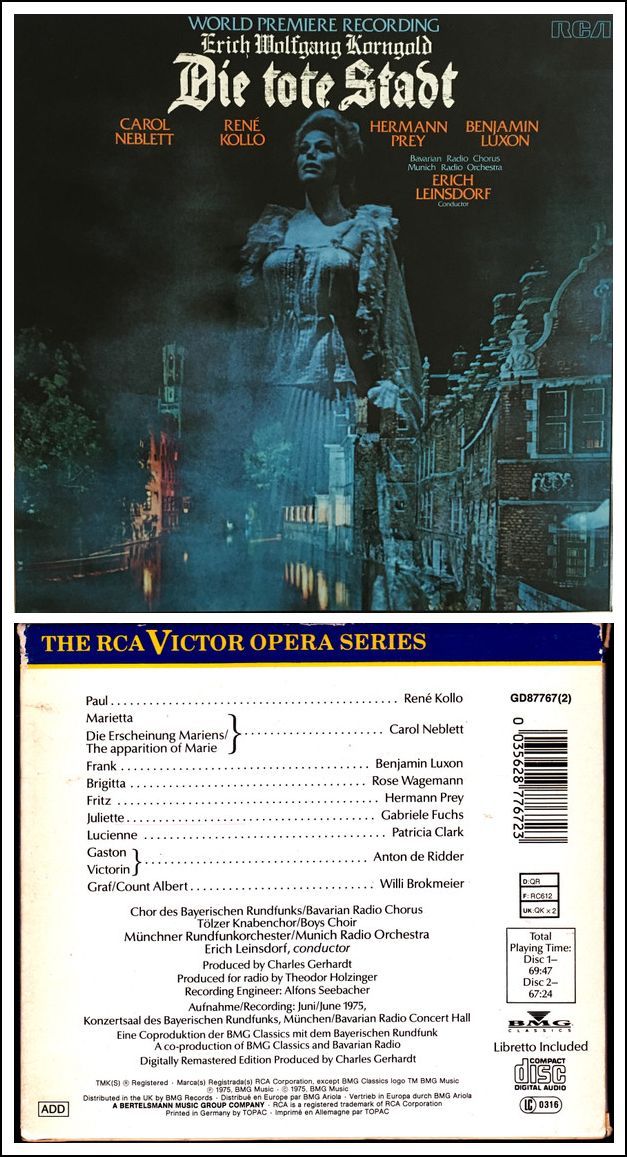

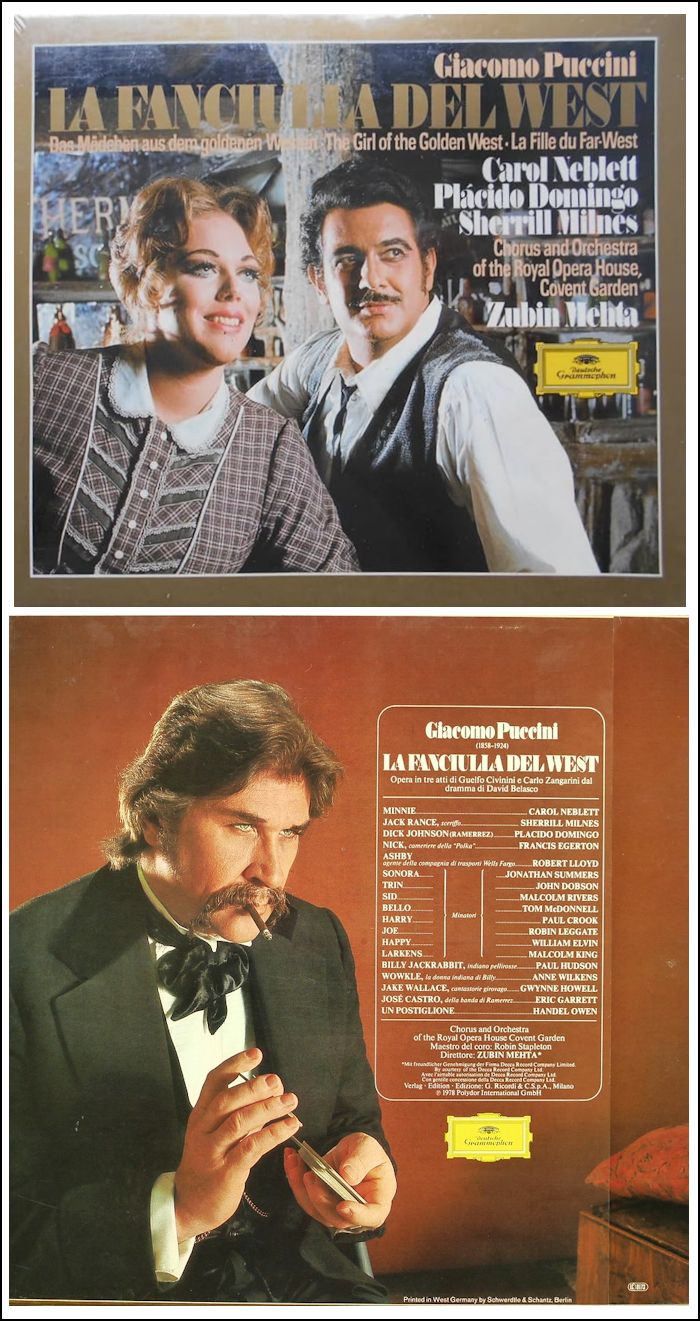

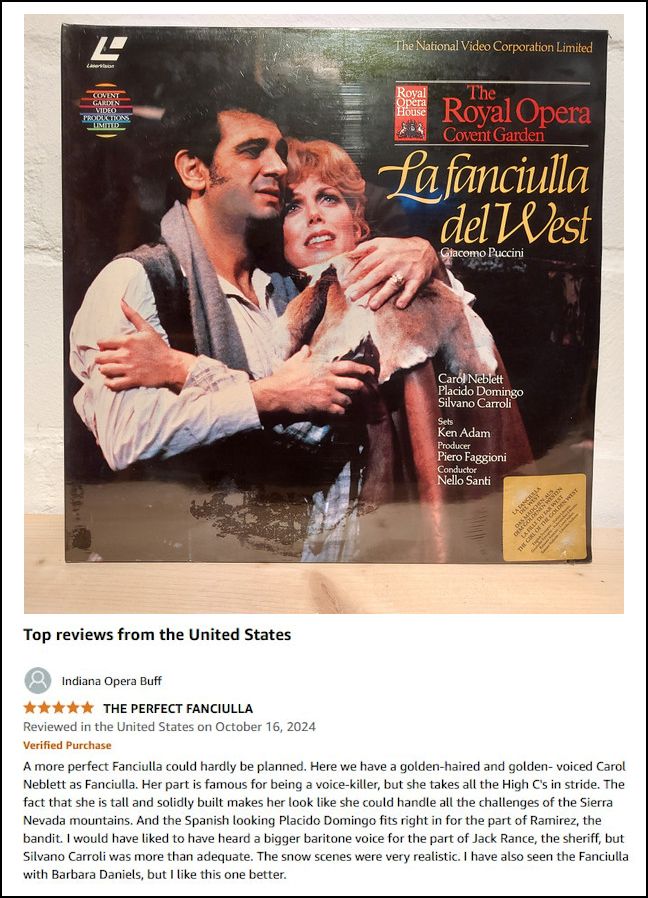

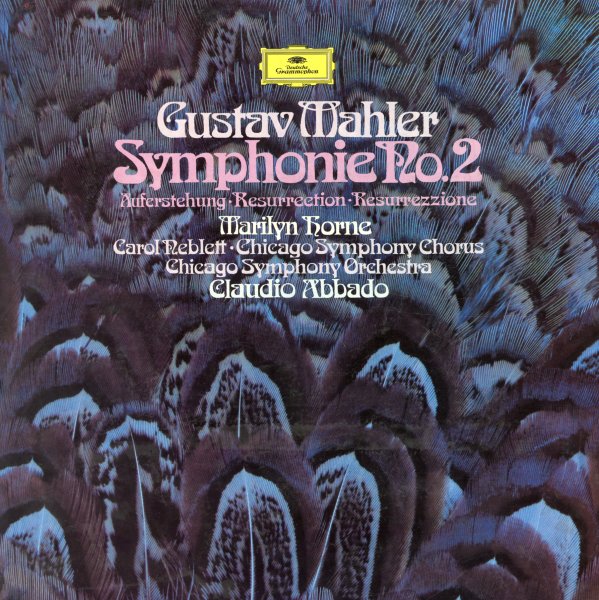

Carol Neblett (February 1, 1946 – November 23, 2017) was born in Modesto, California and raised in Redondo Beach. She studied at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1969 she made her operatic debut with the New York City Opera, playing the part of Musetta in Puccini's La bohème. With that company, she continued to sing many leading roles, in Mefistofele (with Norman Treigle), Prince Igor (conducted by Julius Rudel), Faust, Manon, Louise (opposite John Alexander, later Harry Theyard), La traviata, Le coq d'or, Carmen (as Micaëla, with Joy Davidson, staged by Tito Capobianco), The Marriage of Figaro (as the Contessa Almaviva, with Michael Devlin and Susanne Marsee), Don Giovanni (as Donna Elvira), L'incoronazione di Poppea (with Alan Titus as Nerone), Ariadne auf Naxos (directed by Sarah Caldwell), and Erich Wolfgang Korngold's Die tote Stadt (in Frank Corsaro's production). Her brief nude scene in a 1973 staging of Massenet's Thaïs, for the New Orleans Opera Association, made international headlines. In 1976, she performed Tosca, with Luciano Pavarotti, at the Lyric Opera of Chicago. In 1977, she sang the part of Minnie in La fanciulla del West (one of her great successes), with Plácido Domingo, for Queen Elizabeth II's 25th Jubilee Celebration at Covent Garden. In 1979, she made her Metropolitan Opera debut as Senta in The Flying Dutchman, in Jean-Pierre Ponnelle's production, opposite José van Dam. She sang with the Met until 1993, in such operas as Tosca, La bohème, Un ballo in maschera (with Carlo Bergonzi), Don Giovanni, Manon Lescaut, Falstaff (with Giuseppe Taddei), and La fanciulla del West. During her career, she sang all over the world, including in San Francisco, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, Buenos Aires, Salzburg, Hamburg and London. Her recordings include Musetta in La bohème, with Renata Scotto, Alfredo Kraus, Sherrill Milnes and Paul Plishka, for Angel/EMI, James Levine conducting (1979); La fanciulla del West, with Domingo and Milnes, Zubin Mehta conducting (DGG, 1977); Gustav Mahler's Symphony No.2 ("Resurrection") with Claudio Abbado, Marilyn Horne, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (DGG, 1977); and Marietta in Die tote Stadt, with René Kollo, Hermann Prey, Benjamin Luxon, and Erich Leinsdorf conducting (RCA, 1975). She appeared in several performances on television, including a tribute to George London at the Kennedy Center, Washington, D.C. She also appeared as a guest on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. In 2012, Neblett made her musical theatre debut in a production of Stephen Sondheim's Follies. Neblett was an artist in residence and voice instructor at Chapman

University in Southern California. She was also on the faculty of the International

Lyric Academy in Rome. == Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Carol Neblett with Lyric Opera of Chicago 1975 - Elektra (Chrysothemis) with Brenda Roberts/Schroeder-Feinen, Boese/Mignon Dunn, Stewart/Tyl, Little; Klobucar/Bartoletti 1976 - Tosca (Tosca) with Pavarotti, MacNeil, Tajo, Andreolli; Lopez-Cobos, Gobbi 1977 - Idomeneo (Elettra) with Tappy, Ewing, Eda-Pierre/Shade, Shirley, Little, Kuhlmann; Pritchard, Ponnelle - Callas Tribute Concert with (among others) Vickers, Fournet 1978 - Fanciulla (Minnie) [Opening Night] with Cossutta, Mastromei, Andreolli, Voketaitis, Ballam, Kuhlmann; Bartoletti, Prince 1980 - Don Giovanni (Donna Elvira) with Stilwell/Morris, Dean, Tomowa-Sintow, Winkler, Buchanan, Macurdy; Pritchard, Ponnelle - Italian Earthquake Relief Benefit Concert 1989-90 - Tosca (Tosca) with Jóhannsson, Nimsgern, Tajo; Bartoletti As shown in the LP cover at right, Neblett also sang the Symphony #2 of Mahler with the Chicago Symphony in February of 1976, conducted by Claudio Abbado. The CSO Chorus was under the direction of Margaret Hillis. While Marilyn Horne was on the recording, Claudine Carlson sang the performances at Orchestra Hall. |

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 10, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that evening, and again in 1991 and 1996. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.