|

Bass-baritone James Morris (born January 10, 1947) is world famous for his performances in opera, concert, recital, and recording. With a repertoire including works by Wagner, Verdi, Puccini, Stravinsky, Mussorgsky, Mozart, Gounod and Britten, Mr. Morris has performed in virtually every international opera house and has appeared with the major orchestras of Europe and the United States.

[Vis-ä-vis the recording shown at left, see my interviews

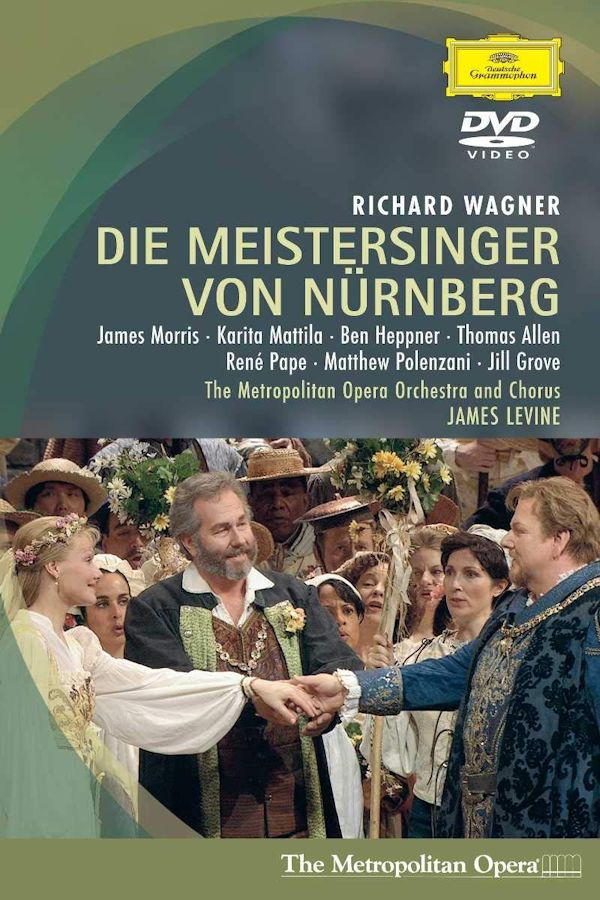

with Judith Blegen,

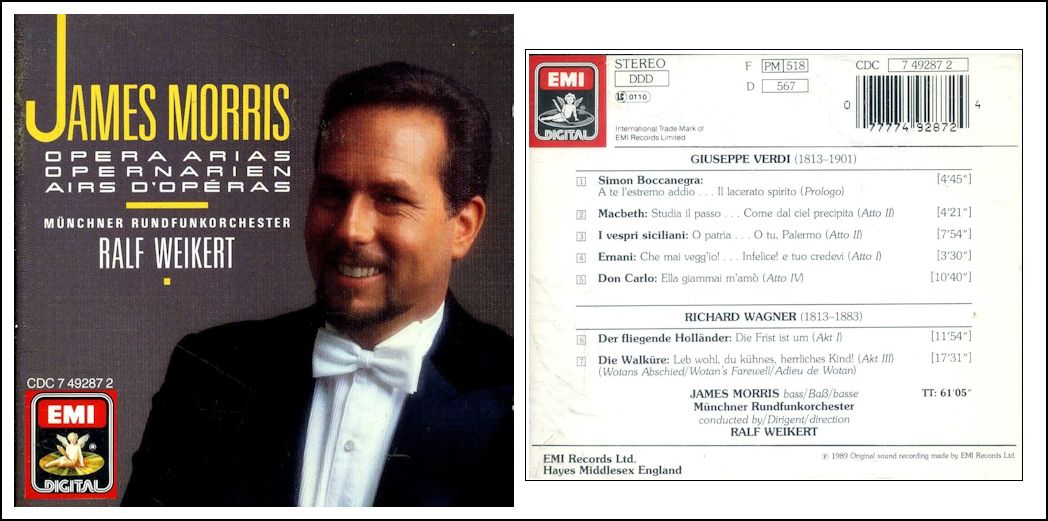

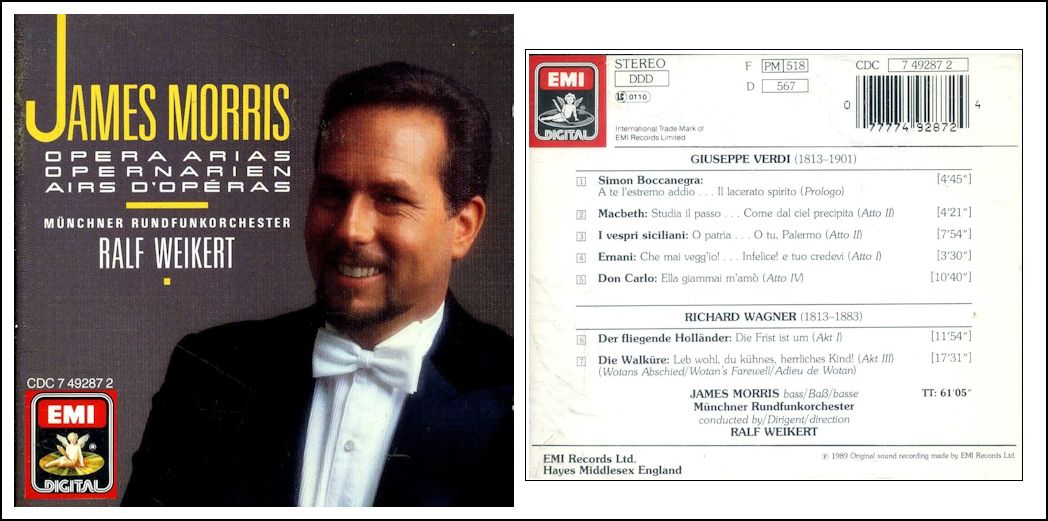

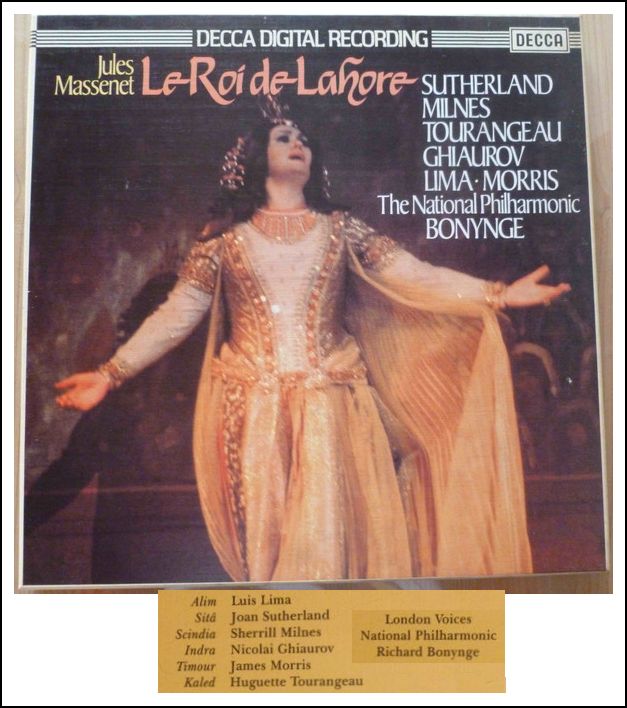

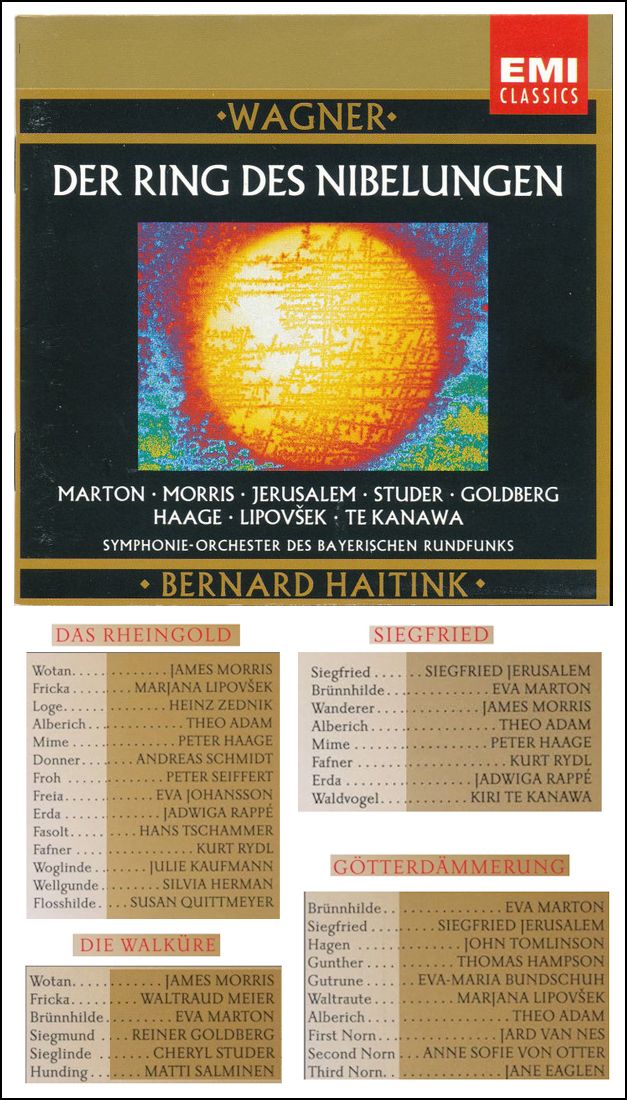

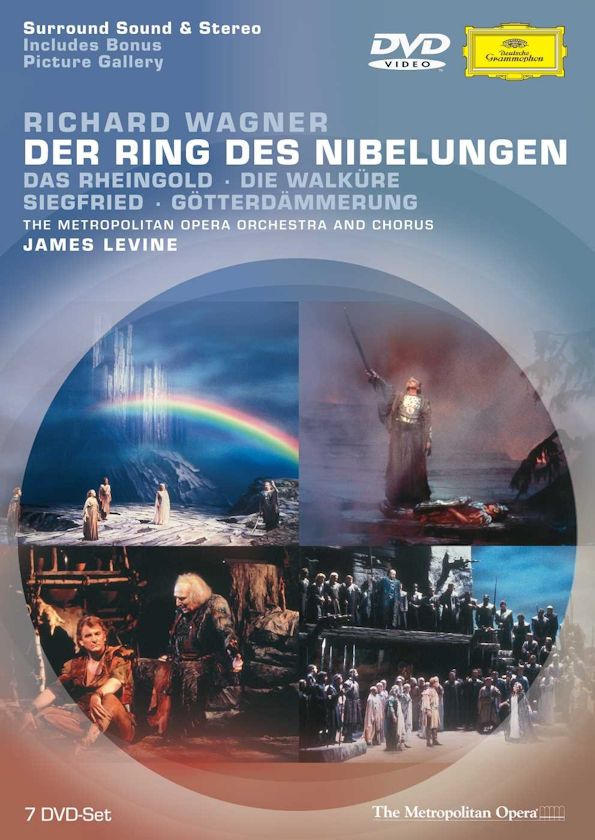

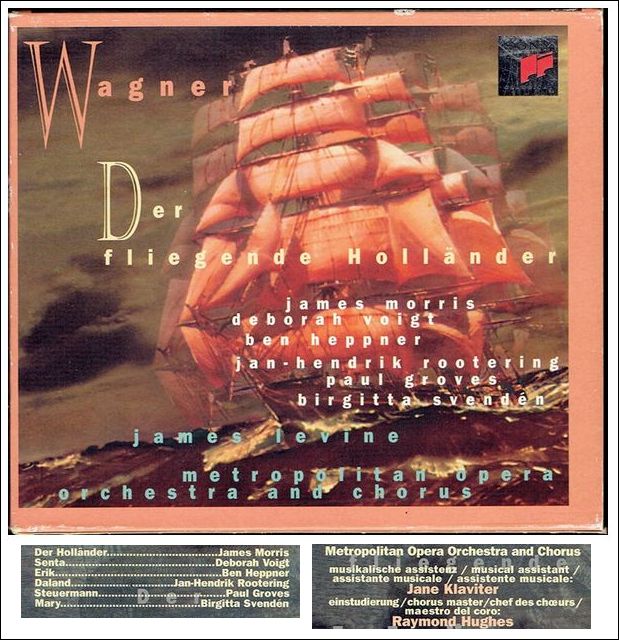

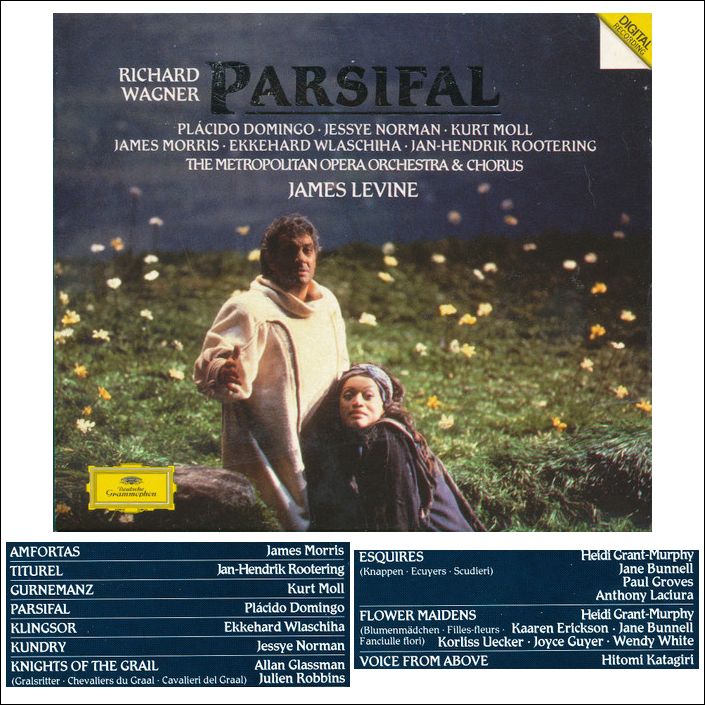

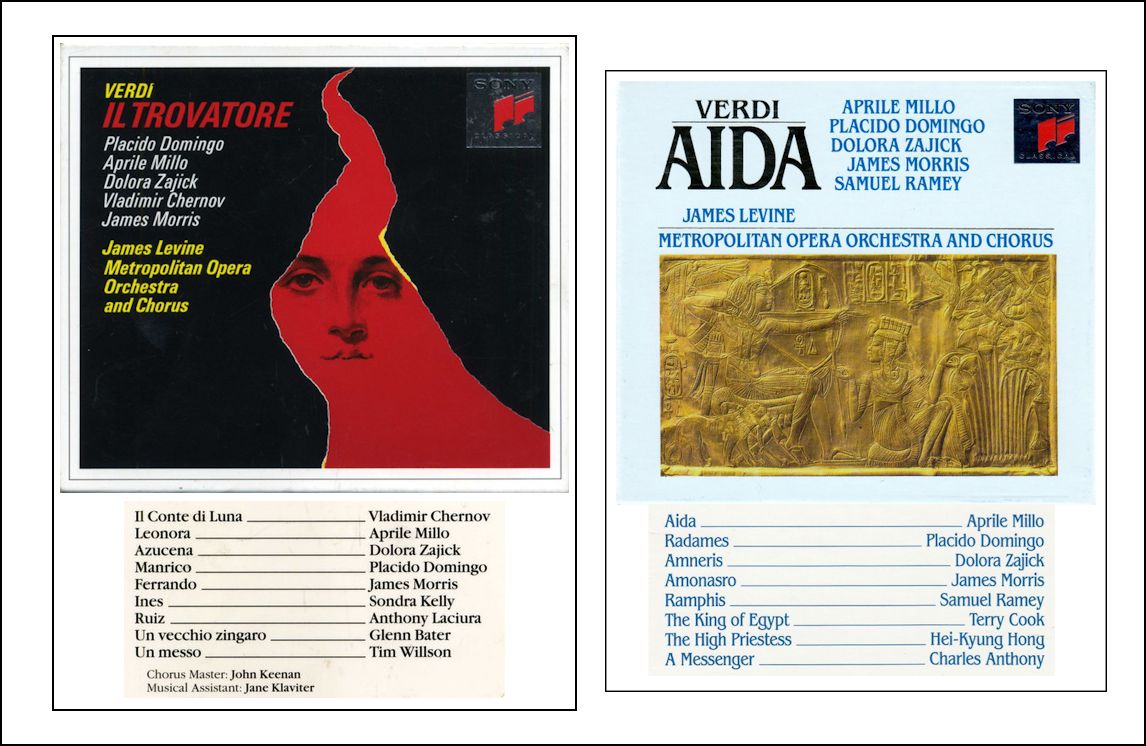

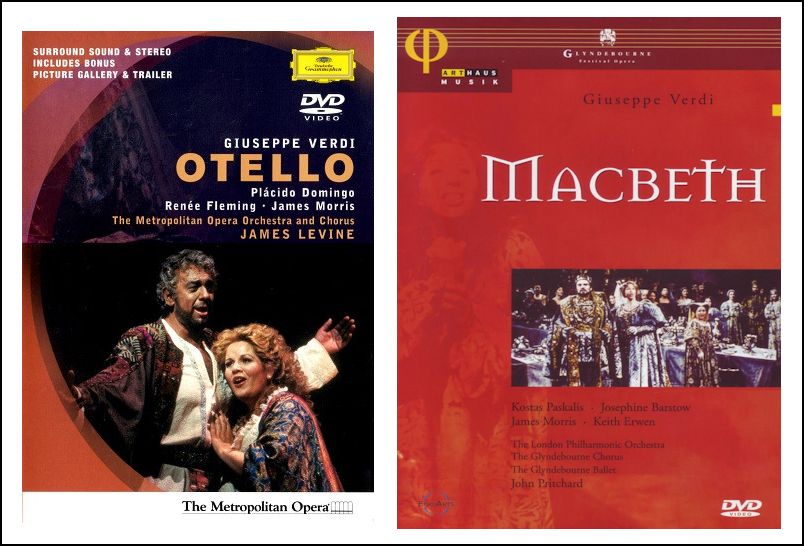

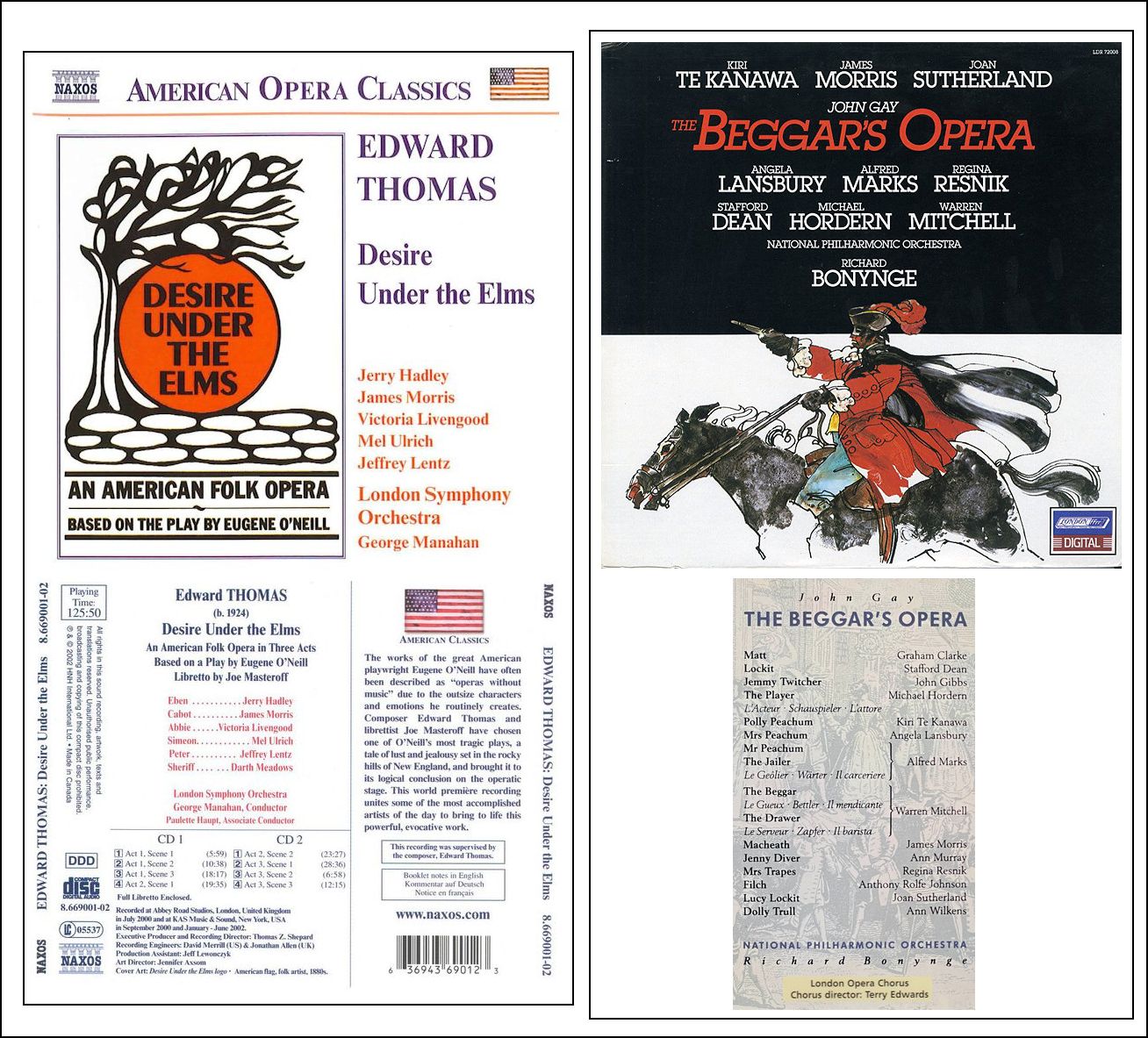

and Robert Shaw.] Mr. Morris’ celebrated career at the Metropolitan Opera has included three complete cycles of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, and Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, both recorded for television and available on DVD. He originated the role of John Claggart in the MET premiere of Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd and has repeated the role in each revival. Frequently performed roles at the MET include the title role in Der fliegende Holländer (new production), Scarpia in Tosca, The Four Villains in Les Contes d’Hoffmann, and the title roles in Don Giovanni and Boris Godunov. Concert appearances have included performances with the world’s celebrated orchestras including the Berlin Philharmonic, London’s BBC Proms, the New York Philharmonic, the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl; the Chicago Symphony and several appearances at the Cincinnati May Festival. He has also appeared frequently in recitals in cities including Minneapolis, Baltimore, Washington D.C. and at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires. Mr. Morris’s extensive discography includes two complete Ring cycles, one for Deutsche Grammophon under James Levine and one for EMI under Bernard Haitink, and other operas of Wagner, Offenbach, Mozart, Massenet, Verdi and Gounod. He has recorded operas by Donizetti, Puccini, Bellini and Thomas with Dame Joan Sutherland, and his orchestral recordings include Haydn’s Creation, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 “Choral” and the Requiems by Mozart and Fauré [shown in this box]. He also has a recording of arias by Verdi and Wagner by Mr. Morris is available on the Angel/EMI label. James Morris is a four-time Grammy winner: for Best Opera Recording for Die Walküre (1989) and Das Rheingold (1990) both with the Metropolitan Opera and for Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 with Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony (Best Classical Album and Best Choral Performance 2009). He was also nominated for Thomas’ Desire Under the Elms (Best Opera Recording 2003), and Siegfried (Best Opera Recording 1992). In 2014 James Morris was appointed to the faculty of the Manhattan School of Music as Professor of Voice. Born and educated in Baltimore, Maryland, Mr. Morris studied at the Peabody Conservatory and studied with Rosa Ponselle. He continued his education at the Philadelphia Academy of Vocal Arts where he studied with basso Nicola Moscona. == Text of biography from Colbert Artists Management

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

|

Among other companies for whom he has directed are the Caramoor

Festival, Canadian Opera, Virginia Opera, and the companies of Charlotte,

Cincinnati, Cleveland, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Portland,

Los Angeles, Seattle, Tulsa, Fort Worth, Vancouver, and Washington

Opera Society, where he was General Manager from 1960 until 1963. Recent notable engagements include a highly acclaimed production

of Der Rosenkavalier for the Florentine Opera, Salome

and Madama Butterfly for the Florida Grand Opera, La

Boheme for The Atlanta Opera, and Dallas Opera to direct La

Traviata and Turandot. His new production

of Aida has been seen at the Florida Grand Opera, Michigan

Opera, and the Florentine Opera and Cincinnati Opera. Recently,

Mr. Hebert returned to Detroit and to Atlanta to revive his famous

production of Turandot. His new production of La

Traviata has been seen at the Florida Grand Opera and the Cincinnati

Opera. This past season, his Aida was seen again in Cincinnati

and Detroit. Well-known as a pianist and vocal coach, he has been associated

with such singers as Callas, Simionato, Price,

Moffo, Tourel, Farrell,

Horne, Verrett, Vickers and Berganza. He worked

as personal music assistant to Igor Stravinsky preparing his vocal

works for performances conducted by the composer. He has staged

15 different productions of Stravinsky's operas. He has also staged the American premieres of Britten's Three

Parables, Henze's

King Stag and Boulevard Solitude, Chabrier's

Le Roi Malgré Lui and Schoenberg's Von Heute

auf Morgen. His productions of Le Rossignol and

Oedipus Rex appear on CBS Records. In addition,

he was Chorus Master on the CBS recording of Boris Godunov

starring George London, and, on other CBS recordings, may be heard

as pianist and harpsichordist in works of Bach, Schoenberg and Berg.

He is pianist on 2 Serenus recordings of contemporary songs for baritone. A native of Faust, New York, and currently residing in France, Mr.

Hebert began his study of piano at the age of 3 and at 5 was appearing

in recitals. Planning a career as a concert pianist, he continued his

musical studies at Syracuse University where he received a B.A. degree

and a Master of Music degree. He was a piano pupil of Robert Goldsand

in New York and of Leila Gousseau in Paris. == Article and photo from Pinnacle Arts Management

=== === === === === === === === === ===

Though born in Thunder Bay, Ontario, McEwen grew up in the Montreal area where he learned to love opera and listened to the Met broadcasts. Aged fourteen, he made a trip to New York one winter break to hear several of his favourite operas, which included Bidú Sayão and Jussi Björling in Rigoletto. As a singer, Sayão was forever to remain his passion, one which was accentuated by seeing her in Manon performances in Montreal. His passion for opera in general led him to visit the Royal Opera House in London and a lowly paid job with Decca Records in that city. Moving up the ranks in the 1950s, he landed in New York in 1959 and for the next 20 years made London Records, Decca's classical arm, the most significant label in the United States. After being approached by San Francisco Opera Director Kurt Herbert Adler regarding a job, McEwen moved to the city in 1980 and immersed himself in learning the operations of an opera company. By January 1982 McEwen was running the Opera. Given his expertise and background in understanding the wonders of the human voice, it is not surprising that his approach in his early years was away from the theatrical and more focused on the vocal. With his Ring Cycle, which began in the Summer 1983 and Fall 1984 seasons (and which was presented in its entirety in June 1985), McEwen demonstrated where his priorities lay: they were focused on hiring the best singers in the world. As a reaction to the economic climate of the times, in 1982 McEwen created the "San Francisco Opera Center" to oversee and combine the operation and administration of the numerous affiliate educational and training programs. Providing a coordinated sequence of performance and study opportunities for young artists, the San Francisco Opera Center includes the "Merola Opera Program", "Adler Fellowship Program", "Showcase Series", "Brown Bag Opera", "Opera Center Singers", "Schwabacher Recitals", and various Education Programs. By introducing his young singers to the great voices of the past, inviting them to rehearsals, and giving tickets to current productions, McEwen hoped to create rounded performers who could appear in the regular Fall season. Amongst his successes in this regard was the mezzo-soprano Dolora Zajick from Nevada. By "hand holding"" her through the various stages of training, he prepared her for the role of Azucena in the summer 1986 season to great acclaim. On 8 February 1988, McEwen announced his resignation. The following day his mentor, Kurt Herbert Adler, died. McEwen died in Honolulu, Hawaii at age 69. == Photo from the San Francisco Chronicle Datebook

|

James Morris with Lyric Opera of Chicago

1979 Simon Boccanegra (Fiesco) with Milnes, Shade, Cossutta, Stone, Toliver; Bartoletti, Frisell, Pizzi 1980 Don Giovanni (Giovanni) with Tomowa-Sintow, Neblett, Dean, Winkler, Buchanan, Bogart, Macurdy; Pritchard, Ponnelle 1992-93 Rheingold (Wotan) with Troyanos, Wlaschiha, McCauley, Maultsby, Petersen, Terfel, Hölle, Ryhänen; Mehta, Everding, Conklin 1993-94 Tosca (Scarpia) with Byrne, Jóhannsson, Woodley, P. Kraus; Bartoletti, Galati, Walton Walküre (Wotan) with Marton, Kiberg, Jerusalem, Lipovšek, Hölle; Mehta, Everding, Conklin 1994-95 Siegfried (Wanderer) with Jerusalem/Schmidt, Clark, Marton/Eaglen, Wlaschiha, Maultsby, Halfvarson; Mehta, Everding, Conklin 1995-96 Don Giovanni (Giovanni) with Orgonasova, Vaness, Terfel/Held, Lopardo, Mentzer/Rost, Scaltritti, Stabell; Kreizberg, Ponnelle *Rheingold (Wotan) with Lipovšek, Wlaschiha, Clark, Maultsby, Petersen, Held, Salminen, Stabell; Mehta, Everding, Conklin *Walküre (Wotan) with Marton/Eaglen, Kiberg, Elming/Anderson, Lipovšek, Salminen; Mehta, Everding, Conklin *Siegfried (Wanderer) with same cast as above without Schmidt 2000-01 Flying Dutchman (Dutchman) with Malfitano, Hawlata, Begley, Gorton, Wottrich; Davis, Lehnhoff 2002-03 Walküre (Wotan) with Eaglen, Voigt, Studebaker/Sanders, Lipovšek, Ens; Davis, Everding, Conklin 2003-04 Siegfried (Wanderer) with Treleaven/Lundberg, Cangelosi, Eaglen, Bryjak, Grove, Aceto; Davis, Everding, Conklin 2004-05 Rheingold (Wotan) with Diadkova, Bryjak, Bottone, Grove, Petersen, Rutherford, Silvestrelli, Aceto; Davis, Everding, Conklin **Rheingold (Wotan) with same principals as above **Walküre (Wotan) with Eaglen, DeYoung, Domingo, Diadkova, Halfvarson; Davis, Everding, Conklin **Siegfried (Wanderer) with same cast as above without Lundberg Fiftieth Anniversary Gala Concert 2007-08, 2009-10, 2011-12 Stars of Lyric Opera at Millennium Park Concerts 2009-10 Tosca (Scarpia) with Voigt, Galouzine, Irvin, Travis; Davis, Zeffirelli 2010-11 Mikado (Mikado) with Churchman, Davies, Blythe, Spence, P. Kraus; Davis, Griffin 2011-12 Tales of Hoffmann (Coppélius/Dappertutto/Lindorf/Dr. Miracle) with Polenzani, Christy, Cambridge,Wall, Fons, Rosel, Cangelosi; Villaume, Joël 2012-13 Meistersinger (Hans Sachs) with Majeski, Botha, Skovhus, Ivashchenko, Barton, Portillo, Silvestrelli; Davis, McVicar [* and ** indicate full Ring cycles] === === === === ===

=== ===

James Morris with the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra & Chorus

Chorus Master Margaret Hillis November, 1977 Requiem [Mozart] with

Costanza Cuccaro, Claudine

Carlson, Vinson Cole;

Carlo Maria Giulini

November, 1981 Creation [Haydn] (Raphael) with Norma Burrowes, Rüdiger Wohlers, Sylvia Greenberg, Siegmund Nimsgern; Sir Georg Solti July, 1991 Oedipus Rex [Stravinsky] (Créon & Messenger) with Philip Langridge, Florence Quivar, Jan-Hendrik Rootering, Donald Kaasch; James Levine |

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 19, 1993. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year to promote the full Ring cycle. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.