Ivan Altchevsky (b. Moscow, 1876; died there,

1917) was one of Hammerstein's new tenors in the season of 1906-1907,

and was described as one who sang with a large quantity of badly

produced sound with dramatic intent, but with a hopelessly faulty

method. He did not stay long in America, but some time later he is said

to have lost his mind and to have been without resources. Ivan Altchevsky (b. Moscow, 1876; died there,

1917) was one of Hammerstein's new tenors in the season of 1906-1907,

and was described as one who sang with a large quantity of badly

produced sound with dramatic intent, but with a hopelessly faulty

method. He did not stay long in America, but some time later he is said

to have lost his mind and to have been without resources. Altschevsky was the son of wealthy parents and had been reared in luxury with the belief that he would inherit large property from his father. When the father died it was found that everything was spent and the property mortgaged. Young Altschevsky was thrown on his own resources. He took to singing, and was able to earn a living by his voice. When Hammerstein heard him he was singing in a cafe at Brussels. After returning to Europe he created the leading role in an opera called "Le Cobzar"' and had surprised the audience by the unusual fervor of his singing and acting. After the performance it was found that he had lost his reason completely. Chaliapin, the Russian basso, organized a benefit for him in Paris. [Bio from The Grand Opera Singers of To-day; An account of the leading operatic stars who have sung during recent years, together with a sketch of the chief operatic enterprises. By Henry C. Lahee. Revised Edition - 1922] *

* *

* *

[The following items are translations from various Russian and Soviet dictionaries and encyclopedias.] Ivan Alchevsky [abroad acted under the name of Jean Altchevsky; Alčevskij; Altschewsky] 15 (27) December 1876, Kharkov - 26 April (May 9) April 27 or May 10), 1917, Baku, buried in Kharkov) was an outstanding Russian opera singer (lyric-dramatic tenor). He was born into a wealthy family. His father was a known banker, businessman and philanthropist, mine owner Alexey K. Alchevsky, the founder of Russia's largest steel plant that he founded (with BB Gerbertsom) in 1895. The Metallurgical Plant and still bears his name - Alchevsky Steel. Ivan's mother Christina Danilovna Zhuravlev-Alchevsk was a teacher, a prominent activist of National Education, created a methodical training system. In 1862 she organized the first free Ukraine girls' school, in 1889 she was elected vice-president of the International League of Education in Paris. Ivan was the fourth or fifth child of a large family. At first Ivan studied music, thought to succeed further in life he entered Kharkov University, where he studied in 1896-1901. But he continued to make music, although intended to devote his life - as his mother did - to teaching activities. The sudden suicide of his father so affected him that he changed his mind. His older brother - who was his first teacher - insistently urged to study singing seriously. With the family in bankruptcy, he had to think about wages. After graduating from Kharkov University, Alchevsky went to Moscow to make his unsuccessful debut at the Bolshoi Theatre, but in 1901 made a successful debut at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg as the Indian Guest in Sadko. He remained for four years singing twenty roles. One critic called him the "singing Rubinstein". In the summer when the theater was not open, he went to Paris to study with Jean de Reszke. He received invitations from La Monnaie in Brussels, and in the summer of 1906 he sang at London's Covent Garden. He then was immediately invited to the Manhattan opera in New York. In 1907 he toured in Boston. Then, returning to Russia in 1907-1908 season he was soloist of the Moscow Opera. In March 1908 he was invited to the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre (Moscow Imperial troupe), however he only sang there for two months, including Hermann in Queen of Spades. In May 1908 at the invitation Diaghilev he sang in Boris Godunov by Mussorgsky in Paris, and in 1910 sang the title role in Samson and Delilah. In 1914 he appeared in Boris Godunov and The Maid of Pskov by Rimsky-Korsakov in London (Drury Lane Theater) with Chaliapin.  Along with the staged operas, he sang a variety of songs in the classical repertoire in Russia and on tour in America and Europe. This included works by his brother, as well as Sergei Prokofiev, M. Glinka, A. Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, Rachmaninov, Lysenko, Yakiv Stepovy, A. Goldenweiser, Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Camille Saint-Saëns and Russian and Ukrainian folk songs. In 1909 he organized the Moscow "Poet" circle, which invited many composers of Ukrainian songs which he performed himself. He also read lectures on musicology and Ukrainian music, and organized Ukrainian music concerts in collaboration with singer Natalia Ermolenko-Yuzhina. During his career, Alchevsky worked very hard and he always helped the needy partners and employees of the theater scene. Once during performances in the Ukraine, he learned that a stagehand died leaving a widow and children without means. The next day went to the cemetary and gave money to his family. In another instance, knowing the value of money, he decided to postpone to repayment of a debt owed to him. He worked in various private troupes just to help them survive. He knew the harsh conditions of small troupes, but understood that they performed for sometimes illiterate, provincial areas of the Russian Empire. He was tired and sick, but appeared in Odessa and was the director of The Queen of Spades by Tchaikovsky. While in Kharkov, Tbilisi, and finally in Baku, he performed even though he was quite sick and exhausted. After an appearance, he was taken to the hospital where died. He was buried in his homeland in Kharkiv.  A Russian dictionary of domestic singers wrote that "Alchevsky possessed absolute pitch, had a wonderful musical memory, used sotto voce, and had an extensive range, freely going to D and E Flat. His lower voice had a baritonal quality, and the upper range had flexibility, enduance and freedom. He sang fifty-five roles, nineteen of them in operas by Russian composers. These comprised heroic dramas and lyric characters." The Great Soviet Encyclopedia says that "Alchevsky had a wide range, a beautiful tone, and was an outstanding performer of chamber music." The magazine Soviet Music, 1949, #10, said that "Alchevsky could create complete vocal and scenic images. His performances were of high artistic culture and had great dramatic power and expressiveness." He recorded eight arias in St. Petersburg in 1903 for G & T and Zonophone and HMV. |

Fernand

Ansseau’s

background was musical. His father played the organ in the village

church of Boussu-Bois near Mons (Wallonia) where the artist was born in

1890. At the age of 17 he entered the Brussels conservatory and became

a student of the noted teacher Désiré Demest. It was in

church music

(Mozart’s Requiem) he

appeared for the first time. Demest trained him as a baritone, but

Ansseau felt that he was making too little progress. His teacher

directed him to change to tenor, noticing his student’s increasing ease

with the upper register. After studying three years with the celebrated

Flemish tenor Ernest van Dijck, Ansseau made his widely acclaimed debut

as Jean in Massenet’s Hérodiade

(the role was to become one of his most successful achievements).

During his career he appeared in roles such as Sigurd, Faust, Julien

and Don José. He was the tenor lead in Saint-Saëns’ first

performance

of Les Barbares. As a Belgian

patriot he refused to appear on the operatic stage during World War I

and sang only occasionally. After the war he resumed his operatic

career at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels, as Canio

(1918).

Particularly in Auber’s liberation opera La Muette de Portici

he was much applauded. His repertory at “The Munt” included Radames,

Samson, The Duke of Mantua, Jean, Don Alvaro, Faust (Berlioz), Des

Grieux (Manon) and Cavaradossi. He remained at this important opera

house until his retirement. 1919 saw his Covent Garden debut, singing

Des Grieux with the soprano Marie-Louise Edvina as Manon and Beecham as

conductor. Ansseau became a well-known singer at Covent Garden and

appeared as Faust, Canio, Cavaradossi and Roméo, opposite Dame

Nelly

Melba. He refused a generous offer by general manager

Gatti-Casazza in

1920 to sing at the Met, not keen to leave home for an extended period.

In 1922 he sang at the Paris Opéra as Jean, Alain (Grisélidis),

Roméo, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Admète (opposite

Germaine Lubin) and

again as Roméo. From 1923 to 1928 he was a regular member of the

Chicago Civic Opera, enjoying remarkable popularity. The “Reigning

Queen”, Mary Garden was full of praise for the tenor, becoming a

favorite partner of the Diva. He was the tenor lead opposite her in

Alfano’s Risurrezione and in

Montemezzi’s L’Amore dei tre Re.

Ansseau spent his active years in Brussels but often reappeared in

Ghent and Antwerp. His last performance at the La Monnaie was in 1939.

His rather early retirement was often linked to the war and given a

patriotic twist, also by Ansseau himself. Some people who knew him

attribute it more to saturation. From 1942 to 1944 he served as a

Professor of Voice at the Brussels conservatory, devoting the following

decades to his hobbies, fishing and gardening. He died in 1972 where

his was born, in Boussu-Bois. Fernand

Ansseau’s

background was musical. His father played the organ in the village

church of Boussu-Bois near Mons (Wallonia) where the artist was born in

1890. At the age of 17 he entered the Brussels conservatory and became

a student of the noted teacher Désiré Demest. It was in

church music

(Mozart’s Requiem) he

appeared for the first time. Demest trained him as a baritone, but

Ansseau felt that he was making too little progress. His teacher

directed him to change to tenor, noticing his student’s increasing ease

with the upper register. After studying three years with the celebrated

Flemish tenor Ernest van Dijck, Ansseau made his widely acclaimed debut

as Jean in Massenet’s Hérodiade

(the role was to become one of his most successful achievements).

During his career he appeared in roles such as Sigurd, Faust, Julien

and Don José. He was the tenor lead in Saint-Saëns’ first

performance

of Les Barbares. As a Belgian

patriot he refused to appear on the operatic stage during World War I

and sang only occasionally. After the war he resumed his operatic

career at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels, as Canio

(1918).

Particularly in Auber’s liberation opera La Muette de Portici

he was much applauded. His repertory at “The Munt” included Radames,

Samson, The Duke of Mantua, Jean, Don Alvaro, Faust (Berlioz), Des

Grieux (Manon) and Cavaradossi. He remained at this important opera

house until his retirement. 1919 saw his Covent Garden debut, singing

Des Grieux with the soprano Marie-Louise Edvina as Manon and Beecham as

conductor. Ansseau became a well-known singer at Covent Garden and

appeared as Faust, Canio, Cavaradossi and Roméo, opposite Dame

Nelly

Melba. He refused a generous offer by general manager

Gatti-Casazza in

1920 to sing at the Met, not keen to leave home for an extended period.

In 1922 he sang at the Paris Opéra as Jean, Alain (Grisélidis),

Roméo, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Admète (opposite

Germaine Lubin) and

again as Roméo. From 1923 to 1928 he was a regular member of the

Chicago Civic Opera, enjoying remarkable popularity. The “Reigning

Queen”, Mary Garden was full of praise for the tenor, becoming a

favorite partner of the Diva. He was the tenor lead opposite her in

Alfano’s Risurrezione and in

Montemezzi’s L’Amore dei tre Re.

Ansseau spent his active years in Brussels but often reappeared in

Ghent and Antwerp. His last performance at the La Monnaie was in 1939.

His rather early retirement was often linked to the war and given a

patriotic twist, also by Ansseau himself. Some people who knew him

attribute it more to saturation. From 1942 to 1944 he served as a

Professor of Voice at the Brussels conservatory, devoting the following

decades to his hobbies, fishing and gardening. He died in 1972 where

his was born, in Boussu-Bois. |

Vittorio

Arimondi

(1861 in Saluzzo - 1928 in Chicago) made his debut (1883) at

Varese in

Gomes's ‘’Il Guarany’’. He made his first La Scala appearance (1893) as

Sparafucile in ‘’Rigoletto’’. In that same year he created the role of

Pistol in the world premiere of Verdi's ‘’Falstaff’’. He then traveled

to London to appear for three seasons at Covent Garden (1894-96). He

sailed to New York and made his Metropolitan Opera debut (7 Dec 1896)

as Ferrando in ‘’Il Trovatore’’. He spent several seasons at

Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera where he was Arkel in the American

premiere of ‘’Pelléas et Mélisande’’. He spent the last

twenty years of

his life in the United States but also made appearances in Poland and

in Russia.

|

Georgy Andreyevich Baklanoff,

known as Georges Baklanoff

(sometimes spelled Baklanov; 4 January 1881 [O.S. 23 December 1880] – 6

December 1938) was a Russian operatic baritone who had an active

international career from 1903 until his death in 1938. Possessing a

powerful and flexible voice, he sang roles from a wide variety of

musical periods and in many languages. He was also highly praised by

audience and critics for his acting abilities. Baklanoff's early career was spent performing

with major theatres in

Russia; including the Bolshoi and Mariinsky theatres. In 1910 he began

performing with important opera houses internationally, and became a

member of both the Boston Opera Company (1910-1915) and the Vienna

State Opera (1912-1914). From 1917-1928 he was the leading baritone in

Chicago and in 1928-1929 he was a member of the Philadelphia Civic

Opera Company. From 1932 until his death in 1938 he was a member of

Theatre Basel. He also appeared as a guest artist with important

theatres internationally. Baklanoff's early career was spent performing

with major theatres in

Russia; including the Bolshoi and Mariinsky theatres. In 1910 he began

performing with important opera houses internationally, and became a

member of both the Boston Opera Company (1910-1915) and the Vienna

State Opera (1912-1914). From 1917-1928 he was the leading baritone in

Chicago and in 1928-1929 he was a member of the Philadelphia Civic

Opera Company. From 1932 until his death in 1938 he was a member of

Theatre Basel. He also appeared as a guest artist with important

theatres internationally.Baklanoff was born Alfons-Georg Bakkis in Riga, Latvia. In 1892 he moved to Kiev after the death of his parents. He initially planned to pursue a career as a lawyer, and studied law at both Kiev University and Saint Petersburg State University. His studies were interrupted due to financial difficulties resulting from the theft of his assets by his legal guardian; a man who eventually committed suicide. He then entered the Kiev Conservatory, and after graduating studied singing for two more years in St. Petersburg with the Russian tenor Ippolit Pryanishnikov. He pursued further training in Milan, Italy in 1902 with Vittorio Vanza. Baklanoff made his professional opera debut in 1903 in Kiev in the title role of Anton Rubinstein's The Demon. That same year he joined the newly formed Zimin Opera. In 1905 he became a member artist at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow where he notably created the title role in the world premiere of Sergei Rachmaninoff's The Miserly Knight and Lanciotto Malatesta in Rachmaninoff's Francesca da Rimini on 24 January 1906. From 1907-1909 he was committed to the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg. There he sang the role of Fyodor Poyarok in the Moscow premiere of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya. In 1910 Baklanoff made debuts with three important companies, the Boston Opera Company (as The Miserly Knight), the Metropolitan Opera in New York City (as Verdi's Rigoletto), and the Royal Opera House in London (as Rigoletto and Scarpia in Puccini's Tosca). Although he never again performed at the Met, he returned frequently to Boston for performances up through 1915. In 1911 he sang Rigoletto for his debut at the Komische Oper Berlin and the title role in Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin for his first performance in France at the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt in Paris. He was soon after engaged as a guest artist at the Paris Opera, the Frankfurt Opera, and with theatres in South America. From 1912-1916 he was a member of the Vienna State Opera. In 1914 he sang in the posthumous world premiere of Amilcare Ponchielli's I mori di Valenza at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo. From 1917-1921 Baklanoff sang with the Chicago Opera Association and from 1922-1928 he performed with the Chicago Civic Opera. In Chicago he sang in the United States premieres of Henry Février's Monna Vanna (1918), Xavier Leroux's Le chemineau (1919, title role), and Rimsky-Korsakov's The Snow Maiden (1923); all at the Chicago Auditorium. Among the roles he sang in Chicago were Amonasro in Verdi's Aïda, Athanaël in Jules Massenet's Thaïs, Escamillo in Georges Bizet's Carmen, the Father in Gustave Charpentier's Louise, King Raimondo in Pietro Mascagni's Isabeau, Méphistophélès in Charles Gounod's Faust, Nilakantha in Léo Delibes' Lakmé, Renato in Verdi's Un ballo in maschera, Rigoletto, Telramund in Richard Wagner's Lohengrin, and Wotan in Wagner's Die Walküre. In 1928-1929 Baklanoff was a member of the Philadelphia Civic Opera Company; singing such roles as Escamillo, Le chemineau, Méphistophélès, and Wotan. In 1929 he performed the title role in the United States premiere of Modest Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov in a concert version with the Philadelphia Orchestra, soprano Rose Bampton, and conductor Leopold Stokowski. He sang with the Philadelphia Orchestra again in 1935 as Agamemnon in the United States premiere of Christoph Willibald Gluck's Iphigénie en Aulide; this time under the baton of Alexander Smallens.

While mainly working in the United States from 1917–1929, Baklanoff continued to appear as a guest artist with major opera houses in Europe during those years and into the 1930s. Some of the theatres with whom he performed were the Bavarian State Opera, the Belgrade National Theatre, the Brno National Theatre, the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb, the Finnish National Opera, the Hungarian State Opera House, the Opéra-Comique, the Royal Danish Theatre, the Royal Swedish Opera, the Vienna Volksoper, and the Zurich Opera. In 1932 he moved to Basel, Switzerland; making his debut with Theater Basel that year in the title role of Mozart's Don Giovanni. He lived in that city until his death there 6 years later, having never retired. At one point during his life he was married to the soprano Lydia Lipkowska.  |

BAROMEO, CHASE

(1892–1973). Chase Baromeo, operatic bass-baritone, was born Chase

Baromeo Sikes, son of Clarence Stevens and Medora (Rhodes) Sikes, on

August 19, 1892, in Augusta, Georgia. He received B.A. (1917) and M.M.

(1929) degrees from the University of Michigan. Before going to the

University of Texas in 1938 to head the voice faculty in the music

department of the new College of Fine Arts, he had a highly successful

operatic career. He made his debut in 1923 at the Teatro Carcano in

Milan, Italy. From 1923 to 1926 he was a member of La Scala in Milan,

where he sang under Arturo Toscanini. BAROMEO, CHASE

(1892–1973). Chase Baromeo, operatic bass-baritone, was born Chase

Baromeo Sikes, son of Clarence Stevens and Medora (Rhodes) Sikes, on

August 19, 1892, in Augusta, Georgia. He received B.A. (1917) and M.M.

(1929) degrees from the University of Michigan. Before going to the

University of Texas in 1938 to head the voice faculty in the music

department of the new College of Fine Arts, he had a highly successful

operatic career. He made his debut in 1923 at the Teatro Carcano in

Milan, Italy. From 1923 to 1926 he was a member of La Scala in Milan,

where he sang under Arturo Toscanini.Because of the Italians' difficulty in pronouncing his last name, Sikes became known professionally as Chase Baromeo, and he used that name for the rest of his life. He also sang at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1924, with the Chicago Civic Opera Company from 1926 to 1931, and with the San Francisco Opera Company in 1935. From 1935 to 1938 he was with the Metropolitan Opera Company in New York. He also performed with many of the leading symphony orchestras in the United States. He was married to Delphie Lindstrom on May 12, 1931; they had three children, one of whom predeceased him. At the University of Texas, Baromeo directed and performed in many university-staged operas. He left the university in 1954 to join the University of Michigan faculty. He died in Birmingham, Michigan, on August 7, 1973. |

| Richard

Bonelli (February 6, 1889 - June 7, 1980) was an American

operatic baritone active from 1915 to the late 1970s. Bonelli was born George Richard Bunn to Martin and Ida Bunn of Port Byron, New York. His family later moved to Syracuse and soon George preferred to be called Richard. Prior to deciding on a career in music, Bonelli was a friend of race car driver and later mayor of Salt Lake City, Ab Jenkins. Bonelli studied at Syracuse University and his voice teachers included Arthur Alexander in Los Angeles, Jean de Reszke and William Valonat in Paris.  Bonelli's operatic debut came on April 21,

1915 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as Valentin in Gounod's Faust.

He toured with the San Carlo Opera Company between 1922 and 1924. He

toured Europe in 1925, making appearances at the Monte Carlo Opera and

La Scala and was eventually engaged by the Théâtre de la

Gaîté in

Paris. Between 1925 and 1931 Bonelli performed with the Chicago Opera

Company and between 1926 and 1942 frequently performed at the San

Francisco Opera. Bonelli's Metropolitan Opera debut came on December 1,

1932 as Verdi's Germont and he remained on the Met's active roster

until 1945, making his final performance as Rossini's Figaro on March

14 that year. He was the Tonio in the first ever live telecast of

opera, from the Met on March 10, 1940 alongside Hilda Burke and Armand

Tokatyan. Of his many roles, Bonelli was known best for his Verdi

roles, and also Wolfram, Tonio, and Sharpless. In Italy, he performed

under the name Riccardo Bonelli. He also appeared in two movies; a

supporting role in 1935's Enter

Madame and a cameo appearance in 1941's The Hard-Boiled Canary. Bonelli's operatic debut came on April 21,

1915 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as Valentin in Gounod's Faust.

He toured with the San Carlo Opera Company between 1922 and 1924. He

toured Europe in 1925, making appearances at the Monte Carlo Opera and

La Scala and was eventually engaged by the Théâtre de la

Gaîté in

Paris. Between 1925 and 1931 Bonelli performed with the Chicago Opera

Company and between 1926 and 1942 frequently performed at the San

Francisco Opera. Bonelli's Metropolitan Opera debut came on December 1,

1932 as Verdi's Germont and he remained on the Met's active roster

until 1945, making his final performance as Rossini's Figaro on March

14 that year. He was the Tonio in the first ever live telecast of

opera, from the Met on March 10, 1940 alongside Hilda Burke and Armand

Tokatyan. Of his many roles, Bonelli was known best for his Verdi

roles, and also Wolfram, Tonio, and Sharpless. In Italy, he performed

under the name Riccardo Bonelli. He also appeared in two movies; a

supporting role in 1935's Enter

Madame and a cameo appearance in 1941's The Hard-Boiled Canary.Totalling performances precisely is chancy, and as regards Bonelli's six prime seasons in Chicago, research has given differing results in certain instances. Numbers thus are approximate but the totals are likely lower than actual. During his heyday in Chicago, Bonelli competed with two powerhouses, each much loved especially by the Italian community. From 1925 to 1931, Giacomo Rimini sang 134 times while Formichi made 175 appearances. A third Italian, Luigi Montesanto, had 47. In contrast, Bonelli racked up 102 performances at home (give or take a few "mysteries") and a further 87 on tour for a grand total of 189. Clearly he had the lion's share, though economics must have been a factor, homegrowns presumably costing less than imports. When he joined the Metropolitan in 1932, several worthy baritones rode the roster but Lawrence Tibbett was clearly king of the roost. During twelve seasons, Bonelli clocked a combined 166 appearances in New York and on tour while Tibbett managed 191. In contrast to his action in Chicago, Bonelli it would seem was under-utilized at the Met. This theory is supported by the fact he sang eighteen roles in six seasons at Chicago and nineteen in twelve at the Met. As for the expected Verdian windfall at the Met, it did not happen, at least not in Chicago numbers. He sang Germont just nine times, Di Luna seven, Rigoletto twice and Amonasro, which gained most attention with an even dozen. In contrast, in Chicago at home and on tour, he sang Verdi's music a total of 92 times! After retiring from singing, Bonelli became a successful voice teacher at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, and in New York. Among his students were Frank Guarrera, Enrico Di Giuseppe, Lucine Amara, and Norman Mittelmann. In 1949 when Edward Johnson retired from his position of general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, Bonelli was a contender for the job though it ultimately went to Rudolf Bing. Bonelli's favorite baritone was Titta Ruffo. American baritone Robert Merrill had stated that Bonelli was his inspiration to study singing, after hearing him perform the Count di Luna at the Met alongside Giovanni Martinelli and Elisabeth Rethberg in 1936. Even after retiring from teaching, he periodically performed on stage into his 80s. His later appearances were more on the West Coast of the United States. He was actor Robert Stack's uncle. Bonelli died in Los Angeles on June 7, 1980 at the age of 91. |

Leon

Cazauran (Tenor) (Bayonne 1879 - ?)  In 1905 he appeared at the Teatro Costanzi

in Rome in I racconti di

Hoffmann

of Offenbach with Maria Farneti (Antonia/Giulietta), Amelia Karola

(Olimpia), Luisa Garibaldi (Nicklausse/madre) and Angelo Scandiani

(Coppelio/dr.Miracolo/Dappertutto). The next year he sang in

Teatro

Regio of Parma as Werther with Elisa Petri (Carlotta), Giuseppe

Giardini (Alberto) and Silvio Becucci (Johann). In 1907 he was hired

for the Manhattan Opera by Hammerstein for Les Contes d’Hoffmann and Thaïs,

but was replaced in both by Charles Dalmorès, who supposedly

learned

the tenor roles in two weeks. It appears that Mr. Cazauran visited the

Bronx Zoo Monkey House and got into the same trouble there as had

Caruso a short time earlier (accused of pinching a woman’s

derrière).

He was, as was Caruso, acquitted, but Hammerstein decided to get rid of

him anyway. Apparently, however, he did sing three performances

as Don

Ottavio in Don Giovanni in

December and January, and the performances of Alexis in Siberia by Giordano in

February. One of his pupils was french tenor Charles Burles who

made his opera debut in 1958. In 1905 he appeared at the Teatro Costanzi

in Rome in I racconti di

Hoffmann

of Offenbach with Maria Farneti (Antonia/Giulietta), Amelia Karola

(Olimpia), Luisa Garibaldi (Nicklausse/madre) and Angelo Scandiani

(Coppelio/dr.Miracolo/Dappertutto). The next year he sang in

Teatro

Regio of Parma as Werther with Elisa Petri (Carlotta), Giuseppe

Giardini (Alberto) and Silvio Becucci (Johann). In 1907 he was hired

for the Manhattan Opera by Hammerstein for Les Contes d’Hoffmann and Thaïs,

but was replaced in both by Charles Dalmorès, who supposedly

learned

the tenor roles in two weeks. It appears that Mr. Cazauran visited the

Bronx Zoo Monkey House and got into the same trouble there as had

Caruso a short time earlier (accused of pinching a woman’s

derrière).

He was, as was Caruso, acquitted, but Hammerstein decided to get rid of

him anyway. Apparently, however, he did sing three performances

as Don

Ottavio in Don Giovanni in

December and January, and the performances of Alexis in Siberia by Giordano in

February. One of his pupils was french tenor Charles Burles who

made his opera debut in 1958.Nov. 17, 1907 New York by direct wire to The Times Something curious seems to be

going on with opera tenors in the monkey house at New York’s Central

Park; perhaps there’s an atmosphere that lends itself to “annoying”

people, for the problem of mashers at the monkey house has even

inspired a 1907 movie by Biograph.

Luckily, Detective J.J. Cain is on the lookout for malefactors who make lewd advances, having arrested Enrico Caruso the year before. Cain’s latest arrests are Leon Cazauran, “a slender young man with pale face and large brown eyes” brought to New York to sing in “Thais” at Oscar Hammerstein’s Manhattan Operahouse, and his companion, Claude Modjeska, “a copper-colored young man,” The Times says. “The charge against both was that of attempting to corrupt the morals of little boys,” The Times says. Cain said he was suspicious of the men because they had visited the monkey house several times before “in the company of small boys.” Despite the language handicap (Cazauran didn’t speak English and while Modjeska only knew a bit of English, he was able to act as a translator) the men protested their innocence. Modjeska was fined $10 and the men vanished.  [The following item is from the Oregon News, November 18, 1907.] SINGER CRUSHED BY HIS ARREST Monkey-House Incident Ruins Career. LEON CAZAURAN BROKEN MAN Sits All Day in Room Wringing His Hands. DROPPED FROM THE OPERA Hammerstein Declares He Will Have Nothing More to Do With Young Tenor Court Dismisses Serious Charge. NEW YORK, Nov. 17. (Special) Trussed and spiritless, Leon Cazauran, the young tenor who came to America two weeks ago to sing in Hammerstein's Opera Company and was arrested near the monkey house in Central Park yesterday, sat all day today in his rooms wringing his hands. He is a delicate, intelligent-looking man of about 27. Mr. Hammersteln will have nothing more to do with him, he says, and that as a singer his career is blasted. "Eet is amazing," he repeated, over and over, and that is all the English he knows," though in French and Spanish he vehemently denies his guilt of the charges on which Detective James J. Cain arrested him that of attempting to corrupt the morals of boys. Finds No Balm or Gilead. The fact that the court did not hold him or his friend, Claude Modjeska, but discharged both after fining Modjeska $10 for having in his possession a bad French photograph, does not lessen his dejection. Cain says he had been watching the two young men for a long time. They had been talking to boys, and in the monkey house had stood with their hands in their coat pockets so close to the boys as to be annoying. The only boy he took along as a witness was 13-year-old Eugene Koch of Rockaway Park. Modjeska, who is a dark-skinned East Indian, born in Bombay, came to America with Cazauran. He is an impersonator, and says he earns a good salary on the stage in Europe. He had plenty of money today, showing nearly $1000 in bills. Career Blasted, Says Modjeska. "This arrest will not hurt me much, except in this country, but for Cazauran It is a tragedy," said Modjeska. "Innocent or guilty, the arrest on such a charge destroys his career. Mr. Hammerstein notified him today that he could not keep his engagement with him." Mr. Hammersteln sent out this statement simply: "A man to whom any suspicion attaches cannot find employment in the Manhattan Opera House." It was intimated, however, by a representative, that Mr. Hammersteln did not believe the charge and that he had not severed his engagement with the young man. Cazauran has a contract, it was acknowledged. |

| [This tiny bit of information is

all that could be found on the internet about this singer. There

were,

however, several photos...] COTREUIL, EDOUARD By Grove Dictionary (b . Paris, 1874), operatic bass, studied at the Paris Conservatoire and made his debut at the Theatre de la Monnaie, Brussels. On his first appearance at Covent Garden, in 1904, he sang Vulcain in Gounod's ' Philemon et Baucis ' ; and in 1919 created there the role of Don Inigo Gomez in Ravel's ' L'Heure Espagnole,' which he sang and acted with notable point and skill. Bibl .- Nokthcott, Covent Garden and the Royal Opera. H. K.     |

Armand

Crabbé

(23 April 1883, Brussels – 24 July 1947, Brussels) was a Belgian

operatic baritone. In 1904 he made his professional opera debut at La

Monnaie as the Nightwatchman in Richard Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

He was a leading performer at the Royal Opera House in London from 1906

to 1914 and again in 1937. He performed with the Manhattan Opera House

from 1907 to 1910 and with the Chicago Grand Opera Company from 1910 to

1914. He made several appearances with the Teatro Colón and La

Scala

during the 1920s. He was active at the Vlaamse Opera up until his

retirement in the early 1940s. Armand

Crabbé

(23 April 1883, Brussels – 24 July 1947, Brussels) was a Belgian

operatic baritone. In 1904 he made his professional opera debut at La

Monnaie as the Nightwatchman in Richard Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

He was a leading performer at the Royal Opera House in London from 1906

to 1914 and again in 1937. He performed with the Manhattan Opera House

from 1907 to 1910 and with the Chicago Grand Opera Company from 1910 to

1914. He made several appearances with the Teatro Colón and La

Scala

during the 1920s. He was active at the Vlaamse Opera up until his

retirement in the early 1940s. |

Désiré

Defrère

(Aug 1, 1888 - Feb 22, 1964) was a baritone and later stage director

with the various Chicago opera companies from 1910-1934. He was

also a

stage director with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.     |

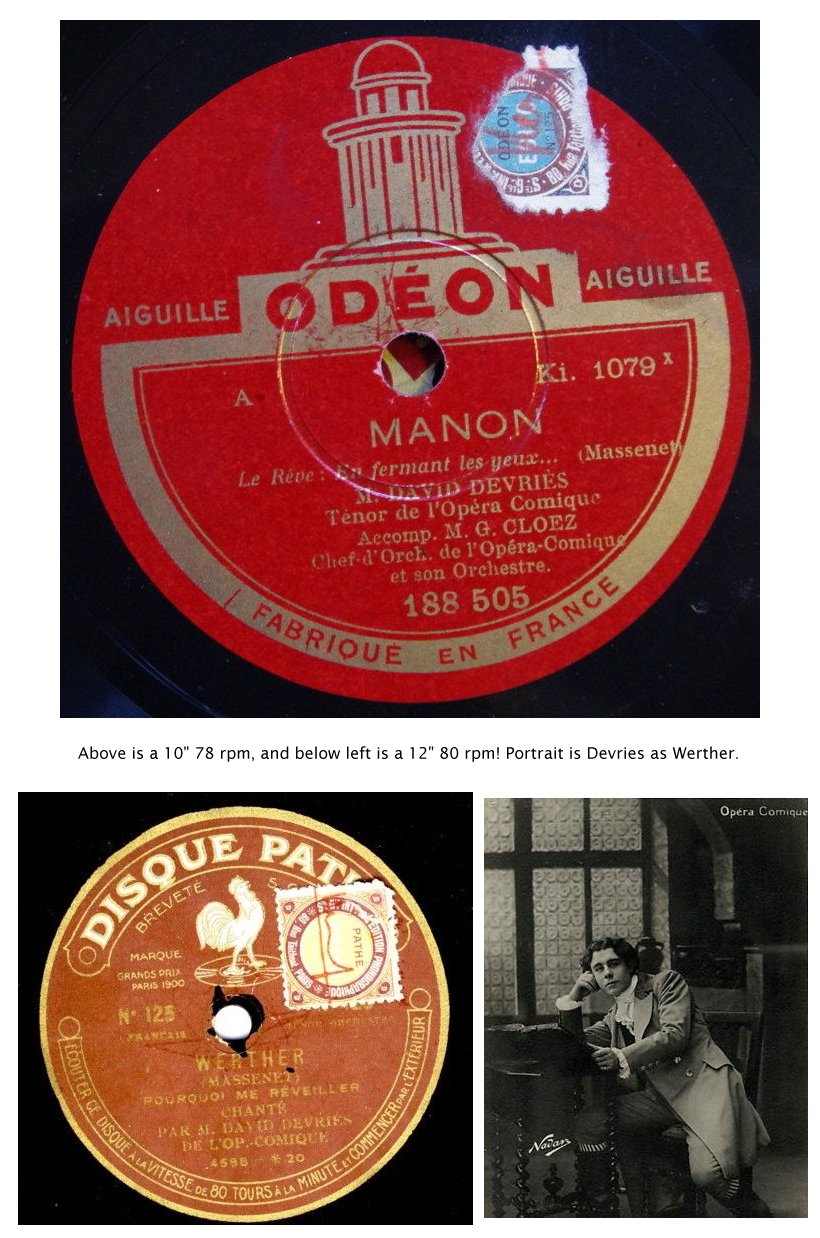

David Devriès

(born February 14, 1881 in Bagnères-de-Luchon, France, died July

17,

1936 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) was a French operatic lyric tenor

noted for his light, heady tone, and polished phrasing. He represents a

light style of French operatic singing that was popular in the 19th

century. David Devriès

(born February 14, 1881 in Bagnères-de-Luchon, France, died July

17,

1936 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) was a French operatic lyric tenor

noted for his light, heady tone, and polished phrasing. He represents a

light style of French operatic singing that was popular in the 19th

century.He was born into a family of professional singers that included soprano Rosa de Vries-van Os (1828–1889) and baritones Hermann Devriès (1858–1949) and his father Maurice Devriès (1854–1919). He studied at the Conservatoire de Paris and débuted in the role of Gérald in Delibes's Lakmé at the Opéra-Comique, where he regularly performed throughout his career. His repertoire included Almaviva, Don José, Toinet in Le chemineau, Clément in La Basoche, Armand in Massenet's Thérèse, Alfredo, Jean in Sapho, Rabaud's Mârouf, Vincent in Mireille, Wilhelm in Mignon, Pedro in Laparra's La habanera, Des Grieux, Werther, Julien, Pinkerton and Cavaradossi as well as principal roles in many forgotten works. He created roles in the operas Aphrodite (Philodème), Les Armaillis (Hansli), Circé (Helpénor), Le roi aveugle (Ymer) and La Victoire (un Brigadier), at the Opéra-Comique. He performed alongside Mary Garden, Luisa Tetrazzini and Dame Nellie Melba. He also gave the world premiere of Boulanger's song cycle Clairières dans le Ciel, which Boulanger claimed was inspired by his voice. In 1909-10 Devriès took part in the final season of Oscar Hammerstein I's Manhattan Opera Company, singing Jean in Jongleur de Notre Dame while Garden was away, thus allowing audiences to hear both versions of the opera that season. Garden and Devriès later sang together in both Grisélidis and Pelléas et Mélisande while on tour with the company in Boston. He created the role of Paco in Manuel de Falla's La vie breve. He was also a very active singer in oratorio, in works ranging from J. S. Bach's St Matthew Passion to Berlioz' The Damnation of Faust. At the Paris Concerts du Conservatoire Devriès sang in the B Minor Mass of J. S. Bach (1908, 1926 and 1931), the St John Passion also of Bach (1914), in Beethoven's Choral Symphony (1926, and at the Beethoven centenary concert in 1927) and the 2nd part of L'enfance du Christ by Berlioz (1931). His son Ivan (born Daniel) Devriès (1909–97), great grandson of Théophile Gautier and Ernesta Grisi, was a composer.  |

Octave

Dua (28 Feb 1882, Ghent - 8 March 1952, Brussels) was a Belgian

operatic tenor. Dua

had a successful career as comprimario. His real name was Leo van der

Haegen. He made his debut in Brussels (Théâtre de la

Monnaie) in 1907

as Jeník in B. Smetana’s The

Bartered Bride. From 1915 to 1922 he

had big success at the Chicago Opera House. From 1919-21 he belonged to

the ensemble of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. In 1921-22 he was

engaged again by the Chicago Opera House (under the management of Mary

Garden). Here he appeared on 30. 12. 1921 in the premiere of S.

Prokofiev's L'amour trois oranges

singing the role of Truffaldino.

In 1920 in New York he had a nasal operation and lost an eye. He had

his biggest success at Covent Garden in London, where he appeared from

1924 to 1931 and again from 1934 to 1939. Here he sang in 1919 in the

première of M. Ravel’s L'Heure

espagnole. In the 1931-1932 season

Dua again was a member of the Chicago Opera House. After 1926 he was

active as a stage manager first in Brussels, then in Ghent.     |

Jean

Duffault |

Hector Dufranne

was born in Mons, Belgium on October 25, 1870. He studied at the

Brussels

Conservatory with Désirée Demest before making his

professional opera

debut in 1896 at La Monnaie as Valentin in Charles Gounod's Faust. He returned to that opera

house several times to sing such roles as Grymping in Vincent d'Indy's Fervaal (1897), Alberich in Richard

Wagner's Das Rheingold

(1898), Thomas in Jan Blockx's Thyl

Uylenspiegel (1900), Thoas in Christoph Willibald Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride (1902),

the Innkeeper in Engelbert Humperdinck's Königskinder (1912), and Rocco

in Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari's I gioielli

della Madonna (1913). Hector Dufranne

was born in Mons, Belgium on October 25, 1870. He studied at the

Brussels

Conservatory with Désirée Demest before making his

professional opera

debut in 1896 at La Monnaie as Valentin in Charles Gounod's Faust. He returned to that opera

house several times to sing such roles as Grymping in Vincent d'Indy's Fervaal (1897), Alberich in Richard

Wagner's Das Rheingold

(1898), Thomas in Jan Blockx's Thyl

Uylenspiegel (1900), Thoas in Christoph Willibald Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride (1902),

the Innkeeper in Engelbert Humperdinck's Königskinder (1912), and Rocco

in Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari's I gioielli

della Madonna (1913).Dufranne sang at the Opéra-Comique in Paris from 1900 to 1912, making his first appearance as Thoas. He appeared in several world premieres with the company including creating the roles of Saluces in Griselidis (1901), the title role in Alfred Bruneau's L' Ouragan (1901), Golaud in Pelléas et Mélisande (1902), Amaury-Ganelon in La Fille de Roland by Henri Rabaud (1904), Koebi in Gustave Doret's Les Armaillis (1906), the title role in Xavier Leroux's Le Chemineau, Clavaroche in Fortunio by André Messager (1907), the fiancé in Raoul Laparra's La Habanéra (1908), and Don Iñigo Gomez in Maurice Ravel's L'Heure espagnole (1911). He also sang Scarpia in the Opéra-Comique’s first production of Giacomo Puccini's Tosca (1909).  Dufranne also appeared periodically at the Paris Opera

beginning in

1907. He notably portrayed the role of John the Baptist in their first

production of Richard Strauss's Salome

(1910). He also sang at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo in 1907 where

he took

part in the creation of two world premieres, the role of André

Thorel

in Jules Massenet's Thérèse

and the title role in Bruneau's Naïs

Micoulin. In 1914 he sang the role of Golaud in his only

appearance at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden in London. Dufranne also appeared periodically at the Paris Opera

beginning in

1907. He notably portrayed the role of John the Baptist in their first

production of Richard Strauss's Salome

(1910). He also sang at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo in 1907 where

he took

part in the creation of two world premieres, the role of André

Thorel

in Jules Massenet's Thérèse

and the title role in Bruneau's Naïs

Micoulin. In 1914 he sang the role of Golaud in his only

appearance at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden in London.In 1908 Dufranne went to the United States for the first time to sing with the Manhattan Opera Company in the American premiere of Pelléas et Mélisande. He returned for several more productions through 1910, appearing as le Prieur in Le jongleur de Notre-Dame (1909), Caoudal in Sapho (1909), Rabo in Jan Blockx's Herbergprinses (performed in Italian as La Princesse d'Auberge, 1909), John the Baptist in Richard Strauss's Salome (1910), and Saluces in Massenet's Griselidis (1910). He also sang with the Chicago Grand Opera Company and the Chicago Opera Association from 1910 to 1922, creating there Léandre in The Love for Three Oranges (in French) by Sergei Prokofiev, in 1921. In 1922, Dufranne returned to Paris where he continued to appear in operas in all the major houses in addition to appearing in other opera houses in France. He also spent a brief time performing in Amsterdam in 1935. In 1923 he created the part of Don Quixote in the stage première of El retablo de maese Pedro under the baton of the composer, Manuel de Falla. The performance was for a private audience and was held in the private theatre of Winnaretta Singer, Princess Edmond de Polignac; he repeated the role in a Falla triple-bill at the Opéra-Comique in 1928. In 1924, he appeared at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in the world premiere of Léon Sachs's Les Burgraves.  With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Dufranne retired from the stage, with his last performance being the role of Golaud at the opera house in Vichy. He lived in Paris where he taught singing for many years before his death on May 4, 1951. His voice is preserved on a number of historic CD recordings made between 1904 and 1928 which have been issued on CYP 3612. He can also be heard on the first full recording of L’heure espagnole (1931), and in extracts from Pelléas et Mélisande (1927).  |

Like

Fernand Ansseau, another Belgian tenor Charles

Fontaine

(1878 - June 8, 1955) was a pupil of Demest at the Brussels

Conservatory. He was born in Antwerp and after making a successful

debut there was invited to Covent Garden for the season of 1909, where

his roles included Faust, Samson and Renaud in a solitary performance

of Gluck's "Armide". The engagement was, however, premature and the

best notices he secured spoke well only of his acting. During the next

two seasons he remained in relative obscurity in the French provinces.

In 1911 he appeared for the first time in Paris, at the Opera as Raous

in "Les Huguenots", in which "his powerful voice, the manner in which

he deployed it, easy and vibrant" made a suitable impression. In the

course of the next three yerars he divided his time between Paris and

appearances at various Belgian theatres. He created the roles of

Lorenzo in “Beatrice” (Messager), Almerio in “Gismonda” (Henry Fevrier)

with Fanny Heldy and Albers. In 1912 he was chosen to record Manrico in

the first complete recording of “Il Trovatore” in French conducted by

Francois Ruhlmann (on 19 acoustic discs). At Antwerp in 1914 with

Yvonne Gall in "Romeo et Juliette", he sang "with a force that quite

subjugated the crowds", the same season at Liege he was Arnold in

"Guillaume Tell" with another leading Belgian singer, the baritone Jean

Noté'. After the German invasion of Belgium in September he

moved to

Paris. At the end of the same year he made his debut at the

Opera-Comique as Don José', after which came Dominique in

"L'Attaque du

moulin", Gerald, Pinkerton, the title role in "Le Jongleur de Notre

Dame", Des Grieux, Canio, Danielo in Leroux's "La Reine Fiammette",

Mylio in "Le Roi d'Ys", Jean in "Sapho", Cavaradossi, Rodolfo, Werther,

Hoffmann, and Armand in Massenet's "Therese". He created Almerio in

Fevrier's "Gisomonda" with Fanny Heldy and Henri Albers. By this time

his singing seems to have much improved and "Le Menestral" picked out

for special praise "his beautiful voice and restrained playing" in

Faure's "Penelope". In the autumn of 1917 he sang in a special gala

evening of excerpts from French opera at La Scala. In December 1918 he

became a member of the Chicago Opera. During his first season in which,

as a result of the presence of Mary Garden as principal prima donna,

fourteen of the twenty-nine works in the repertory were French, he

shared the principal tenor roles with Lucient Muratore and John

O'Sullivan. Although unable to produce the high notes that made the

latter celebrated and without Muratore's charm of manner or good looks,

he secured a repeat engagement the following season and appeared with

Garden in "Carmen", "Louise", "Gismonda", "Cleopatre", and "Thais". He

took the role of Toliak in Gunsbourg's "Le Vieil Aigle" with Baklanov,

and Pierre in Messager's "Madame Chrysantheme" with the Japanese

soprano Tamaki Miura. When it was repeated on tour at the Lexington

Theatre in New York, Aldrich noted that: [Fontaine] as Pierre

showed

an agreeable tenor voice, a little uneven in quality, and sometimes a

little disposed to flat but with plenty of power, and in his

impersonation was vigorous and manly. He remained active through

the

1920s in Paris and the French provinces at Bordeaux, Nice (with

Rittter-Ciampi in "Les Contes d'Hoffmann") and elsewhere. A comparison

between Ansseau and Fontaine in "O Paradis" reveals obvious

similarities in voice production but Fontaine is a cruder singer; the

intervals are not as clearly defined, the voice is rather throaty and

when he piles on the pressure, the top notes become strained.

Throughout there are signs of the disagreeable effects of the

diphthonged French vowels, and he has a tendency to articulate the

words at the expense of the quality of the tone. Next to Ansseau, or

Franz, this is dry and lacking in sonority. When a less scrupulous

delivery does not come amiss, in Sigurd's "Esprits gardiens", he makes

a brazen effect sweeping easily through the high tessitura. Like

Fernand Ansseau, another Belgian tenor Charles

Fontaine

(1878 - June 8, 1955) was a pupil of Demest at the Brussels

Conservatory. He was born in Antwerp and after making a successful

debut there was invited to Covent Garden for the season of 1909, where

his roles included Faust, Samson and Renaud in a solitary performance

of Gluck's "Armide". The engagement was, however, premature and the

best notices he secured spoke well only of his acting. During the next

two seasons he remained in relative obscurity in the French provinces.

In 1911 he appeared for the first time in Paris, at the Opera as Raous

in "Les Huguenots", in which "his powerful voice, the manner in which

he deployed it, easy and vibrant" made a suitable impression. In the

course of the next three yerars he divided his time between Paris and

appearances at various Belgian theatres. He created the roles of

Lorenzo in “Beatrice” (Messager), Almerio in “Gismonda” (Henry Fevrier)

with Fanny Heldy and Albers. In 1912 he was chosen to record Manrico in

the first complete recording of “Il Trovatore” in French conducted by

Francois Ruhlmann (on 19 acoustic discs). At Antwerp in 1914 with

Yvonne Gall in "Romeo et Juliette", he sang "with a force that quite

subjugated the crowds", the same season at Liege he was Arnold in

"Guillaume Tell" with another leading Belgian singer, the baritone Jean

Noté'. After the German invasion of Belgium in September he

moved to

Paris. At the end of the same year he made his debut at the

Opera-Comique as Don José', after which came Dominique in

"L'Attaque du

moulin", Gerald, Pinkerton, the title role in "Le Jongleur de Notre

Dame", Des Grieux, Canio, Danielo in Leroux's "La Reine Fiammette",

Mylio in "Le Roi d'Ys", Jean in "Sapho", Cavaradossi, Rodolfo, Werther,

Hoffmann, and Armand in Massenet's "Therese". He created Almerio in

Fevrier's "Gisomonda" with Fanny Heldy and Henri Albers. By this time

his singing seems to have much improved and "Le Menestral" picked out

for special praise "his beautiful voice and restrained playing" in

Faure's "Penelope". In the autumn of 1917 he sang in a special gala

evening of excerpts from French opera at La Scala. In December 1918 he

became a member of the Chicago Opera. During his first season in which,

as a result of the presence of Mary Garden as principal prima donna,

fourteen of the twenty-nine works in the repertory were French, he

shared the principal tenor roles with Lucient Muratore and John

O'Sullivan. Although unable to produce the high notes that made the

latter celebrated and without Muratore's charm of manner or good looks,

he secured a repeat engagement the following season and appeared with

Garden in "Carmen", "Louise", "Gismonda", "Cleopatre", and "Thais". He

took the role of Toliak in Gunsbourg's "Le Vieil Aigle" with Baklanov,

and Pierre in Messager's "Madame Chrysantheme" with the Japanese

soprano Tamaki Miura. When it was repeated on tour at the Lexington

Theatre in New York, Aldrich noted that: [Fontaine] as Pierre

showed

an agreeable tenor voice, a little uneven in quality, and sometimes a

little disposed to flat but with plenty of power, and in his

impersonation was vigorous and manly. He remained active through

the

1920s in Paris and the French provinces at Bordeaux, Nice (with

Rittter-Ciampi in "Les Contes d'Hoffmann") and elsewhere. A comparison

between Ansseau and Fontaine in "O Paradis" reveals obvious

similarities in voice production but Fontaine is a cruder singer; the

intervals are not as clearly defined, the voice is rather throaty and

when he piles on the pressure, the top notes become strained.

Throughout there are signs of the disagreeable effects of the

diphthonged French vowels, and he has a tendency to articulate the

words at the expense of the quality of the tone. Next to Ansseau, or

Franz, this is dry and lacking in sonority. When a less scrupulous

delivery does not come amiss, in Sigurd's "Esprits gardiens", he makes

a brazen effect sweeping easily through the high tessitura.   |

Cesare

Formichi

(April 15, 1883, Rome - July 21, 1949, Rome) was a prominent Italian

operatic baritone, particularly associated with the Italian repertory. Formichi

studied in Rome with Lombardo, and made his

debut in December 1907 at the Teatro Olimpia in Bologna as Lescaut in Manon.

He went on to appear in Italy's leading opera houses, including La

Scala in Milan. Soon, he was accepting a string of engagements to sing

outside Italy, notably in Saint Petersburg (in 1912), Buenos Aires (in

1914), Paris (in 1922), Monte-Carlo, Vienna, and London (in 1924). Formichi

studied in Rome with Lombardo, and made his

debut in December 1907 at the Teatro Olimpia in Bologna as Lescaut in Manon.

He went on to appear in Italy's leading opera houses, including La

Scala in Milan. Soon, he was accepting a string of engagements to sing

outside Italy, notably in Saint Petersburg (in 1912), Buenos Aires (in

1914), Paris (in 1922), Monte-Carlo, Vienna, and London (in 1924).He sang as first baritone at the Chicago Opera from 1922 until 1932. He sang in Berlin in October 1933 with the Italian opera conducted by Ettore Panizza. He went with a troupe of singers from La Scala on a tour of France in 1935, and later organized opera seasons in London. Notable roles of his included Ashton, Rigoletto, di Luna, Amonasro, Iago, and some Wagner parts sung in Italian (Klingsor, for example). Formichi possessed a big, rich-toned, important sounding voice which can be heard on the numerous acoustic and electrical recordings which he made during the peak of his career. Many of these recordings have been re-released on CD.  |

|

|

Gustave Huberdeau (10 May 1874 – 31 May 1945) was a French operatic bass-baritone who had a prolific career in Europe and the United States during the first quarter of the twentieth century. He sang a wide repertoire encompassing material from French composers like Gounod and Massenet to the Italian grand operas of Verdi, the verismo operas of Mascagni, and the German operas of Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss. He sang in numerous premieres during his 30 year career, including the original production of Puccini's La rondine in 1917. Although possessing a rich and warm voice, Huberdeau had a talent for comedic portrayals which made him a favorite casting choice in secondary comedic roles as well as leading roles. After retiring from opera in 1927, Huberdeau remained active as a performer in stage plays and in French cinema throughout the 1930s. Huberdeau was born in Paris, studied at the Paris Conservatoire and then made his professional opera début at the Opéra-Comique in 1898. He sang in smaller roles with that theater over the next ten years, which included a number of secondary roles in premières such as Charpentier's Louise (1900), Camille Erlanger's Le Juif polonais, Massenet’s Grisélidis (1901), Reynaldo Hahn's La Carmélite (1902), Henri Rabaud's La fille de Roland (1904), and Guillaume in André Messager's Fortunio (1907). In 1908 he joined the roster of Oscar Hammerstein I's Manhattan Opera Company in New York City where he periodically sang leading roles over the next three years. He notably portrayed the Devil in the American première of Grisélidis and sang Orestes in the American première of Elektra (1910). However, Hammerstein employed Huberdeau more frequently in productions with the Philadelphia Opera Company with which he was highly active between 1909 and 1910. In 1911 Huberdeau became a member of the Chicago Grand Opera Company, remaining with that company until it closed in 1914. He appeared in several notable productions with the company including the American premiere of Wilhelm Kienzl's Der Kuhreigen and the world premiere of Victor Herbert's Natoma. In 1914 he debuted at England's Royal Opera as a visiting artist, where he sang Méphistophélès from Gounod's Faust. That same year he returned to France and served in the First World War in the French army. After being honorably discharged in 1917, Huberdeau joined the Chicago Opera Association where he sang leading roles until 1920. He notably sang in the world premiere of Sylvio Lazzari's Le Sautériot (1918), the American premiere of Henry Février's Gismonda, and the world premiere of Reginald De Koven's Rip Van Winkle (1920). In 1917 Huberdeau sang the role of Rambaldo Fernandez in the original production of Puccini's La rondine with Opéra de Monte-Carlo. In 1919–1920 he sang with the Beecham Opera in London where he appeared as Méphistophélès, Le Comte des Grieux in Massenet's Manon, Ramfis in Verdi's Aïda, and Colline in La Bohème. He also periodically returned to Covent Garden appearing as Arkel and the Father in the British première of Mascagni’s Iris (1919) among other roles. In 1921 Huberdeau returned to France where he continued to sing throughout the 1920s in such cities as Paris, Nice, Monte Carlo, Vichy, and Brussels. He sang a wide repertory, which included everything from lead roles to character roles to mute roles. In 1922 he sang in the world premiere of Massenet's Amadis. In 1924 he left France for one year to perform in a number of productions in Amsterdam which included Zuniga in Bizet's Carmen and Golaud in the Dutch premiere of Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande. In 1927, Huberdeau sang his last season in Monte Carlo, which included a portrayal of Hunding in Wagner's Die Walküre. After his opera career ended, Huberdeau continued to perform as an actor on the stage in spoken plays and in French films. His first film role was in the 1931 movie Ronny. His other film appearances include Boule de gomme (1931), Le Million (1931), Mistigri (1931), La Dame de chez Maxim's (1932), Prisonnier de mon coeur (1932), Georges et Georgette (1933), Les Nuits moscovites (1934), Tarass Boulba (1936), and À Venise, une nuit (1937). With the outbreak of World War II, Huberdeau's acting career ended. He died in Paris in 1945. Huberdeau was among the first generation of musicians to be recorded. He recorded only a few arias around 1910 on Edison cylinder. His recordings show a sturdy voice that is somewhat dry in quality given the limited technology of day. [Photo below: Huberdeau as Palemon in Thaïs.]  |

Marcel

Journet

(July 25, 1868 – September 7, 1933), was a French, bass, operatic

singer. He enjoyed a prominent career in England, France and Italy, and

appeared at the foremost American opera houses in New York City and

Chicago. Journet

was born in the town of Grasse, Alpes-Maritimes near Nice, and studied

at the Paris Conservatory with Louis-Henri Obin. He made his operatic

debut at Montpellier in 1891. Journet went on to sing a wide range of

roles in operas by Richard Wagner and major French and Italian

composers during a distinguished, 40-year career. Journet

was born in the town of Grasse, Alpes-Maritimes near Nice, and studied

at the Paris Conservatory with Louis-Henri Obin. He made his operatic

debut at Montpellier in 1891. Journet went on to sing a wide range of

roles in operas by Richard Wagner and major French and Italian

composers during a distinguished, 40-year career.He sang Balthazar in Donizetti’s La Favorite at Bézières (Belgium) in 1892. From 1892 he sang regularly at the La Monnaie in Brussels. His international career began with an invitation to Covent Garden in 1897, where the bass roster included Edouard de Reszke and Pol Plançon. Their presence notwithstanding, Journet was engaged every season until 1907 and he reappeared in 1909, 1927 and 1928. He made his debut at the Met in 1900. He sang the following bass- and baritone roles: Marcel and St. Bris in Les Huguenots, the Landgrave in Tannhäuser, Méphistophélès in Gounod’s Faust, Claudius in Thomas’ Hamlet, Jupiter and Vulcain in Gounod’s Philémon et Baucis, Colline and Schaunard in La Bohème, Capulet and Frère Laurent in Roméo et Juliette, Leporello and the Commendatore in Don Giovanni, Sparafucile in Rigoletti, the Kings in Lohengrin and Le Roi d’Ys, Escamillo and Zuniga in Carmen, Raimondo in Lucia di Lammermoor, Don Basilio, Comte des Grieux in Manon, Basinde in Missa’s Maguelone, Alvise in La Gioconda, Rodolfo in Catalani’s Loreley, Fafner in Rheingold, Garrido in La Navarraise, the King and Ramfis in Aïda, Ferrando in Il Trovatore, the Grand Inquisitor and the Grand Brahmin in L’Africaine, Titurel and Gurnemanz in Parsifal, Myrtille and Olimpias in de Lara’s Messaline, Lodovico in Otello, Oberthal and Zacharias in Le Prophète, Tom in Ballo in Maschera, Narr-Havas in Reyer’s Sallambô, Plunkett in Martha and many others. In 1915 he sang with the Chicago Opera. In 1916 he appeared in South America where he returned in 1923 and 1927. From the time of the outbreak of World War I he began to base the major portion of every season in France. At the Paris Opéra he had to compete again with two other basses, André Gresse and Jean-Francisque Delmas. It was in Monte Carlo, however, that Journet reigned as first bass from 1914 to 1920. He also held this position at La Scala where he sang his roles including Simon Mago in the first performance of Boito’s Nerone. Remaining active throughout the 1920s he gave his last performance a year before he died. His career was one of the most long lasting in history. |

| Alexander

Kipnis

(February 13 [O.S. February 1] 1891 – May 14, 1978) was a Russian-born

operatic bass. Having initially established his artistic reputation in

Europe, Kipnis became an American citizen in 1931, following his

marriage to an American. He appeared often at the Chicago Opera before

making his début at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City in

1940. Aleksandr Kipnis was born in Zhytomyr, the capital of the Volhynian Governorate, in the Russian Empire (now Ukraine). His impoverished family of seven lived in a Jewish ghetto. After his father died, when he was aged 12, he helped support the family as a carpenter's apprentice and by singing soprano in local synagogues and in Bessarabia (now Moldova) until his voice changed. As a teenager he took part in a Yiddish theatrical group, until he entered the Warsaw Conservatory at age 19. The conservatory did not require a high-school diploma. His education included the study of the trombone, double bass and conducting. All the while he continued to sing in synagogues. On the recommendation of the choirmaster, he traveled to Berlin and studied voice with Ernst Grenzebach who was also a teacher of Lauritz Melchior, Meta Seinemeyer, and Max Lorenz. At the same time he sang second bass in Monti's Operetta Theater.  When

the First World War started, Kipnis was interned as an alien in a

German holding camp. While singing to himself he was overheard by an

army captain whose brother was general manager of the Wiesbaden Opera.

Kipnis was released from custody and he was engaged by the Hamburg

Opera. He made his operatic debut in 1915, singing three Johann Strauss

songs as a "guest" in the party scene of the operetta Die Fledermaus.

In 1917, he moved to the Wiesbaden Opera, having gained invaluable

stage experience. He sang in more than 300 performances at Wiesbaden

until 1922, when he joined the Berlin Staatsoper. When

the First World War started, Kipnis was interned as an alien in a

German holding camp. While singing to himself he was overheard by an

army captain whose brother was general manager of the Wiesbaden Opera.

Kipnis was released from custody and he was engaged by the Hamburg

Opera. He made his operatic debut in 1915, singing three Johann Strauss

songs as a "guest" in the party scene of the operetta Die Fledermaus.

In 1917, he moved to the Wiesbaden Opera, having gained invaluable

stage experience. He sang in more than 300 performances at Wiesbaden

until 1922, when he joined the Berlin Staatsoper.The following year Kipnis visited the United States with a touring Wagnerian company. For nine seasons, between 1923 and 1932, he was on the roster of the Chicago Civic Opera. In 1927, at the Bayreuth Festival, he appeared as Gurnemanz in Wagner's Parsifal under Karl Muck and recorded the Good Friday Music under Siegfried Wagner. (A purported live performance recording in 1933 under Richard Strauss has been generally discounted.) He also appeared at the Salzburg Festival. Kipnis was under contract with the Berlin Opera until 1935, when he was able to break his contract and flee Nazi Germany. He appeared for three seasons as a guest performer with the Vienna State Opera in 1936-1938. Just after the Anschluss he left Europe and settled permanently in the United States. By the time he was finally signed by the Metropolitan in 1940 he had appeared in most of the world's major opera houses. In addition to those European and American theatres already mentione, he was heard at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, (in 1927 and 1929–1935), and also at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires (1926–1936). Kipnis was regarded throughout the inter-war years as being one of the greatest basses in the world. He was praised for the beauty of his smooth and mellow voice and the excellence of his musicianship. As befitted his status, he was invited to appear with the top conductors of his day. He retired from the Met in 1946. He made his last concert appearance in 1951. Since his debut in 1915, he had sung at least 108 roles, often in more than one language, and his performances in opera and oratorio numbered more than 1600. He died in Westport, Connecticut in 1978, aged 87. Kipnis' son Igor Kipnis (1930–2002) was a celebrated harpsichordist. [See my Interview with Igor Kipnis.] Following in similar creative footsteps, Kipnis's grandson, Jeremy R. Kipnis (born 1965), has become known as a photographer, record producer, film director, and recently creator of The Kipnis Studio Standard - The 21st Century Ultimate Screening Room Design, an evolution of George Lucas's and Tom Holman's THX Motion Picture & Sound Standards. “My father was born into a pitifully poor family in the Ukraine and had little going for him as a young boy except for a rather sweet soprano voice. One day, a visiting cantor from Bessarabia heard the lad singing in the local synagogue choir and persuaded my father’s mother, with the promise of some payment, to let him take the child back to his own synagogue to sing. During this period of a few years, my father was befriended by one of the choir’s male singers. The town of Novybug, with its largely unpaved streets, had particularly muddy paths when the post-winter thaws came and whenever it rained. In exchange for singing lessons and the rudiments of reading music, my father would scrupulously scrub the rubber boots of the older singer. One of the pieces the older man introduced him to was “Der Leiermann,” the haunting final song from Schubert’s Winterreise. My father was affected by the sad, almost frozen tune of the organ grinder, and in later life he often related how, as a young boy, he loved songs in minor keys and could not understand why anyone should ever want to write in the major mode.” (Igor Kipnis)  |

Tenor Forrest Lamont

was Canadian by birth, but he spent most of his life in the United

States. Opera engagements took him all over the world, and he sang with

some of the world's finest singers in major cities such as New York and

Chicago. Born

in the Ontario village of Athelone, in the Adjala Township, Forrest

Lamont moved with his family to Chicopee, Massachusetts where he

studied music and sang in church choirs. He continued his studies in

France, Italy and Germany, and on May 18, 1914 he made his operatic

debut at the Teatro Adriano in Rome in Donizetti's Poliuto.

In the same year, he made a guest appearance in Moscow, and engagements

followed throughout Europe with performances in Italy, Vienna and

Budapest. Born

in the Ontario village of Athelone, in the Adjala Township, Forrest

Lamont moved with his family to Chicopee, Massachusetts where he

studied music and sang in church choirs. He continued his studies in

France, Italy and Germany, and on May 18, 1914 he made his operatic

debut at the Teatro Adriano in Rome in Donizetti's Poliuto.

In the same year, he made a guest appearance in Moscow, and engagements

followed throughout Europe with performances in Italy, Vienna and

Budapest.In 1916, Lamont returned to the United States, and joined the Chicago Civic Opera Company. The company's director, Campanini, actively supported the efforts of American opera composers, and Lamont had the opportunity to perform the lead in a number of American operas. One of Lamont's earliest appearances on the Chicago Opera stage took place on December 26, 1917 in the world premiere of Azora, Daughter of Montezuma by American composer Henry Hadley. Lamont appeared in the role of Xalca in this three-act Romantic opera that "was a sort of junior American Aïda, with a call for lavish staging, processionals, ballets, colorful costuming, big musical numbers". In 1918, Lamont appeared in the premiere of an opera that dealt with the American Civil War, Daughter of the Forest, by American composer Arthur Nevin. In the same year, the Chicago Opera presented a season at the Lexington Theater in New York City, and in this venue, Lamont appeared in Azora, Daughter of Montezuma again and in Donizetti's Linda di Chamounix with the popular soprano Amelita Galli-Curci. Other American operas in which he appeared include Hardling's Light From St. Agnes and Frank Patterson's The Echo. Between 1919 and 1920, he made ten recordings on the Okeh label, including arias from Pietro Mascagini's Cavalleria Rusticana and Giuseppe Verdi's Il Trovatore. Lamont sang with the Chicago Civic Opera until 1930, specializing in performances of Wagnerian, French and Italian opera. He appeared in a wide variety of roles, including Rodolfo in La Bohème, Radames in Aïda, Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor, the Duke in Rigoletto, Dmitri in Boris Gudonov, Canio in Pagliacci, Alfred in Die Fledermaus, Turiddu in Cavalleria Rusticana and Siegmund in Die Walküre. One of his greatest successes occurred in 1921 when he sang the role of Gennaro in E. Wolf-Ferrari's The Jewels of the Madonna with Giacomo Rimini and Rosa Raïsa. Forrest Lamont also joined the Cincinnati Civic Opera and made guest appearances with the Philadelphia Opera Company. Between his engagements in the United States Lamont made international tours, visiting cities in the West Indies and South America. After he retired from the concert stage, he became a voice teacher in Chicago. He lived in Chicago until his death in 1937.   |

|

Alfred

Maguenat

In 1911 the Pathé Company began an ambitious

project to record

complete

operas in French. This series includes eleven operas and preserves the

unique French style of singing, a tradition that is completely lost

today. Pathé commissioned Jean-Charles Nouguès

(1875-1932), the

composer of Quo Vadis (1909)

to create an opera specifically for the relatively new phonograph. This

was a first in the history of recording. Les Frères Danilo was born

in 1911. There is no evidence of Les

Frères Danilo ever being staged and therefore, the only

way to hear this opera is on the recording which was re-issued on

Marston! In 1911 the Pathé Company began an ambitious

project to record

complete

operas in French. This series includes eleven operas and preserves the

unique French style of singing, a tradition that is completely lost

today. Pathé commissioned Jean-Charles Nouguès

(1875-1932), the

composer of Quo Vadis (1909)

to create an opera specifically for the relatively new phonograph. This

was a first in the history of recording. Les Frères Danilo was born

in 1911. There is no evidence of Les

Frères Danilo ever being staged and therefore, the only

way to hear this opera is on the recording which was re-issued on

Marston! The performers include Henri Albers (Baritone), Marguerite Mérentié (Mezzo Soprano), Alfred Maguenat (Baritone), Edmond Tirmont (Tenor), Pierre Dupré (Bass). The composer, Jean Nouguès, conducts. The recording was made c. 1912. In 1928, Columbia recorded extensive excerpts from Pelléas et Mélisande in which Maguenat sang Pelléas. It was re-released on Pearl and VAI. |

René

Maison

(24 November 1895 - 11 July 1962) was a prominent Belgian operatic

tenor, particularly associated with heroic roles of the French, Italian

and German repertories. Born in Frameries, Belgium, he studied in

Brussels and Paris. He made his debut in Geneva in 1920, as Rodolfo in La bohème.

He also appeared in Nice and Monte Carlo, before making his debut in

1927, at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, as Prince Dimitri in Franco

Alfano's Risurrezione,

opposite the soprano Mary Garden. His other roles there included Don

José, Mylio, Werther, Canio, Cavaradossi, and Jean Gaussin in

Massenet's Sapho. Born in Frameries, Belgium, he studied in

Brussels and Paris. He made his debut in Geneva in 1920, as Rodolfo in La bohème.

He also appeared in Nice and Monte Carlo, before making his debut in

1927, at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, as Prince Dimitri in Franco

Alfano's Risurrezione,

opposite the soprano Mary Garden. His other roles there included Don

José, Mylio, Werther, Canio, Cavaradossi, and Jean Gaussin in

Massenet's Sapho.He made his Paris Opéra debut at the Palais Garnier in 1929, in Henry Février's Monna Vanna. He sang there regularly until 1940, as Faust, Lohengrin, Radames, Siegmund and Samson. In 1934, he created there the role of Eumolphe in Stravinsky's Perséphone. Maison also enjoyed a successful international career, appearing at the Chicago Civic Opera (1928-40), the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires (1934-37), the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in London (1931-36), and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. His Met debut occurred on February 3, 1936, as Stolzing in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. In eight seasons with the Met he sang Don José, Lohengrin, Samson, Julien, Florestan, Hoffmann, des Grieux and Herodes, among other roles. In 1943, he began teaching at the Juilliard School in New York, and from 1957 until his death, at the Chalof School in Boston. Among his pupils was the baritone turned dramatic tenor Ramon Vinay. Maison died in Mont-d'Or, France, aged 66. He was, in terms of birth dates, the middle member of a triumverate of outstanding Belgian operatic tenors who reached their peak in the period between the two world wars. The others were the lyric-dramatic tenor Fernand Ansseau (1890-1972) and the lyric tenor Andre D'Arkor (1901-1971). Maison possessed a powerful and penetrating voice, capable of surprising nuance, and an impressive stage presence (he stood 6 feet 4 inches tall). Posterity is fortunate that he made some commercial, 78-rpm discs of French operatic arias which demonstrate his considerable merits as a singer. |

Riccardo

Martin (November 18, 1874 – August 11,

1952) was an American tenor. Riccardo

Martin (November 18, 1874 – August 11,

1952) was an American tenor.Born Hugh Whitfield Martin in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, Martin began his career at Columbia University studying music composition under Edward MacDowell. It was while studying at Columbia that Martin's vocal talents were discovered. In 1901 he was granted an endowment by industrialist Henry Flagler to study to further his vocal studies in Paris with Giovanni Sbriglia, Jean de Reszke and Léon Escalaïs. Martin later completed his studies with Vincenzo Lombardi in Florence and Beniamino Carelli in Naples. He debuted as Faust in Nantes in 1904. Two years later he made his American debut in New Orleans, singing with the visiting San Carlo Opera. Martin bowed at the Metropolitan Opera on November 20, 1907 in Mefistofele; the performance also marked the American debut of Fyodor Chaliapin. Martin remained with the Metropolitan through the 1914-15 season, appearing in numerous leading tenor roles; he was among the first American-born leading men the company employed. He returned for the 1917-18 season. During his tenure at the Met, he created the lead tenor roles in three American operas: Walter Damrosch's Cyrano, Horatio Parker's Mona, and Frederick Shepherd Converse's The Pipe of Desire. After leaving the company he appeared with numerous companies throughout America and Europe, and spent three seasons with the Chicago Civic Opera. Martin died in New York City in 1952. Martin is known to have married at least three times during his life according to both newspaper accounts and vital records. He first married in 1899, Elfrida Hildegarde Klamroth, a fellow opera singer who was more widely known by the stage name of Ruano Bogislav. The couple had one child named Beth Martin who was commonly and professionally known as Bijie Martin. The couple divorced before 1920 largely as a result of career differences. Martin went onto marry an aspiring actress in 1923 named Jane Grey which also ended in divorce. His last known marriage was in 1932 to Allis Beaumont, who recently became famous as Allis Beaumont Reid in the documentary "Must Read After My Death" (2007).  |