Mezzo-Soprano / Soprano Janis Martin

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Janis Martin (born 16 August

1939) is an American opera singer who sang leading roles first as a mezzo-soprano

and later as a soprano in opera houses throughout Europe and the United

States.

She was born in Sacramento, California and studied at California State

University-Sacramento and the University of California-Berkeley. She began

studying singing in Sacramento with Julia Monroe and later studied in New

York with Lili Wexberg and Otto Gruth. She made her operatic debut in 1960

at San Francisco Opera as Theresa in La

sonnambula, and at 21 was the youngest member of the company that

season. She continued to sing a number of comprimario mezzo-soprano roles

with the company through 1969, including Sister Anne in the 1961 world premiere

of Norman Dello

Joio's opera Blood Moon.

[Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.]

She returned as a soprano in 1970 in the title role of Tosca and appeared there regularly though

1990, when she sang the role of Brünnhilde in Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung for the company's

complete performance of Wagner's Ring

Cycle.

On 23 March 1962 she had won the National Finals of Metropolitan Opera

National Council Auditions singing "Mon cœur s'ouvre à ta voix" from

Samson et Dalila, and later

that week made her New York City Opera debut as Mrs. Grose in The Turn of the Screw. Her Metropolitan

Opera debut came on 19 December 1962 when she sang Flora Bervoix in La traviata with Anna Moffo as Violetta.

She went on to sing 147 performances at the Met between 1962 and 1997,

first in mezzo-soprano roles, including Singer in the 1964 US premiere

of Menotti's The Last Savage and from 1973 leading

soprano roles including Kundry in Parsifal,

Marie in Wozzeck, Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and the

title role in Tosca. Her final

appearance with the company was in 1997 when she sang Brünnhilde in

Die Walküre with Plácido

Domingo as Siegmund and Deborah

Voigt as Sieglinde.

Martin sang with the Deutsche Oper Berlin from 1971 to 1988 and at the

Bayreuth Festival from 1968 to 1973, also in 1989, and 1995-1997. She retired

from the stage in 2000 to live in Nevada County, California, where she gives

singing lessons and occasional recitals and concerts.

--------

Martin died December 14, 2014 in San Antonio, Texas.

|

Janis Martin visited in Chicago in six seasons -- five at Lyric Opera (as

seen in the box below) and in May of 1976 at Orchestra Hall for The Flying Dutchman with the Chicago

Symphony conducted by Sir

Georg Solti (as seen at right). The cast included Norman Bailey, René

Kollo, Martti Talvela,

and Werner Krenn, and the chorus was prepared (as always) by Margaret Hillis. The

concert-version was presented both in Chicago and at Carnegie Hall, and

then recorded.

During her visit in the fall of 1980, she graciously took time to visit

the studios of WNIB for a conversation. I

don't remember exactly why it came up, but we spoke briefly about being

forgetful.....

Janis Martin:

Thank goodness I remember my parts!

Bruce Duffie:

Do you use a prompter?

JM: Sometimes,

but sometimes the prompter doesn't know just what you want when you look

down to him. He should give everything all the time.

BD: [Surprised]

Don't they speak all the lines regularly?

JM: Some do

and some don't. Some think they're bothering you by giving you your

text, but if all of a sudden you need it and they are just then deciding

not to give it to you, that's when you need it -- and it's too late by

the time you've looked down and they've looked down and found the line.

Sometimes you do use them because you're not a machine and you can have

a blackout, and you don't want to have it go on forever, or sometimes you

might twist a word around, or get the next sentence one sentence too early

and it wouldn't work out with the music.

BD: Do you

sing your roles in more than one language?

JM: There's

one opera that I've done in three languages and I'm going to probably do

it in my fourth -- Bluebeard's Castle,

which I did here in Chicago in 1970. That I've done in English, German,

and Italian, and now Maestro Bartoletti

wants me to do it in Florence for the Maggio Musicale in Hungarian.

I told him I would if I have time to come for four days rehearsals for

the staging, and he said he wanted me on any condition. So I'll try

to work it out. I'm very busy at that time, and then to learn it

in Hungarian... Right now I could learn it very easily because there

are a lot of Hungarians around this area.

BD: This station

where you are right now has a Hungarian-language program, and the guy has

been doing it for forty years! [With a gentle nudge] Solti

is in town right now, so you could go to him!

JM: [Laughs]

Oh yes, I'm sure he has a lot of spare time to do that for me!

BD: Did you

like the staging here? [The production

at Lyric Opera had one small door at the back-center of the stage, and

each time it opened and the cyclorama "opened" and revealed projections

over the entire back and sides of the stage to go with each new door.]

Janis Martin at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1970 - Bluebeard's Castle (Judith)

with David Ward; Bartoletti, Puecher

1971 - Tosca (Tosca) with Bergonzi, Gobbi, Andreolli; Sanzogno,

Gobbi

1972 - Walküre (Sieglinde)

with Nilsson, Hofmann,

Esser, Hoffmann, Rundgren; Leitner, Lehmann, Grübler

1980 - Lohengrin (Ortrud) with

Johns, Marton, Roar, Sotin, Monk; Janowski, Oswald,

1982 - Tristan und Isolde (Isolde)

with Vickers, Denize, Nimsgern, Sotin, Negrini, Cook; Leitner, Poettgen,

Oswald

|

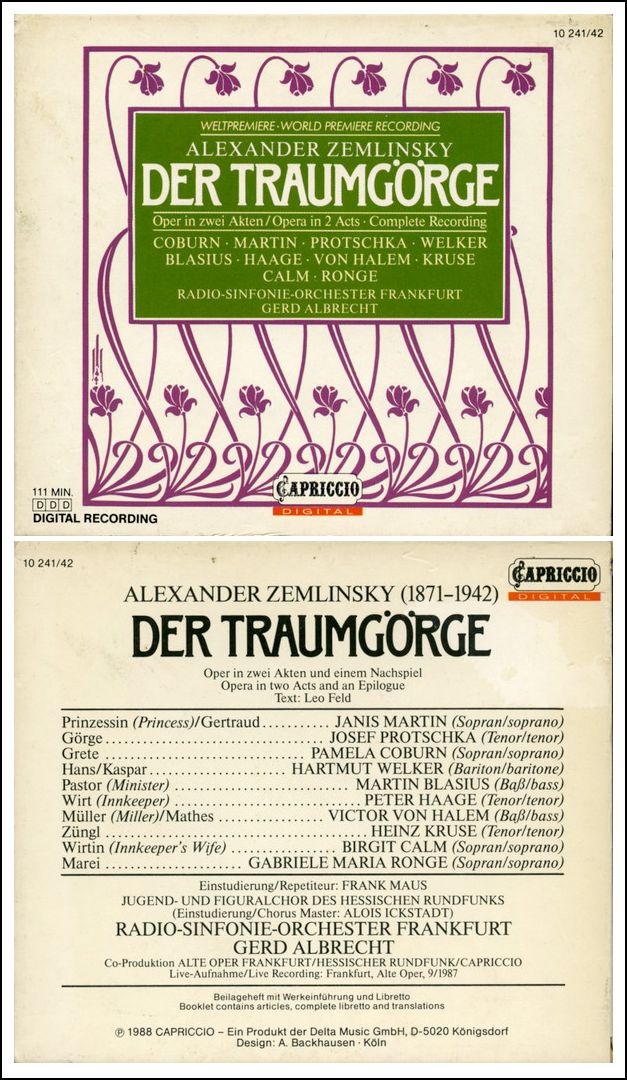

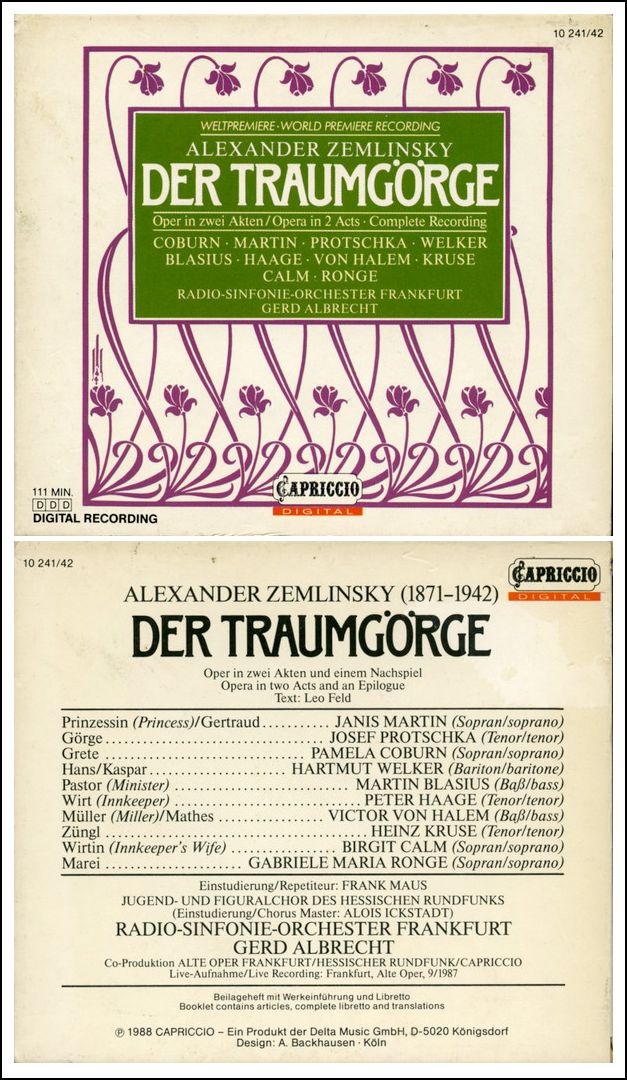

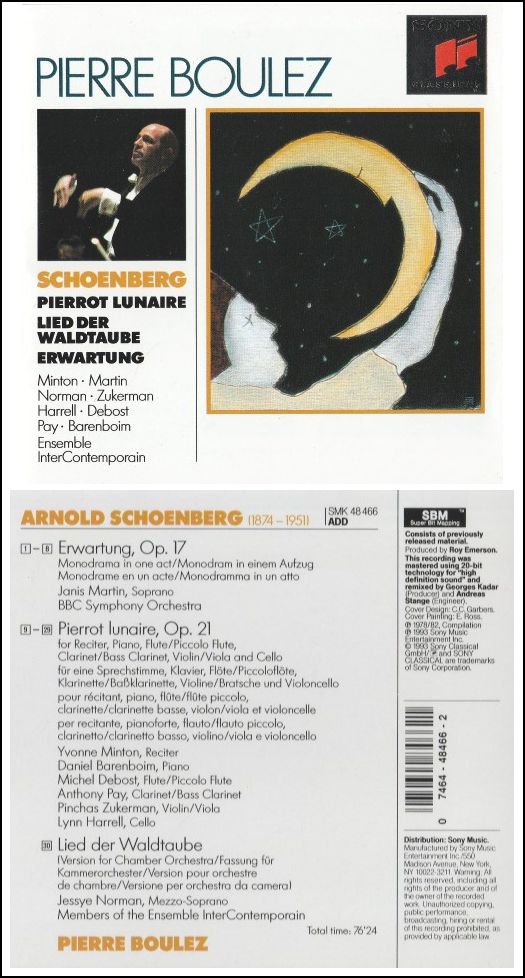

JM: I've also

done it on a ramp where there were not the doors, but each time a light would

come on along the ramp. That was enough in a small theater.

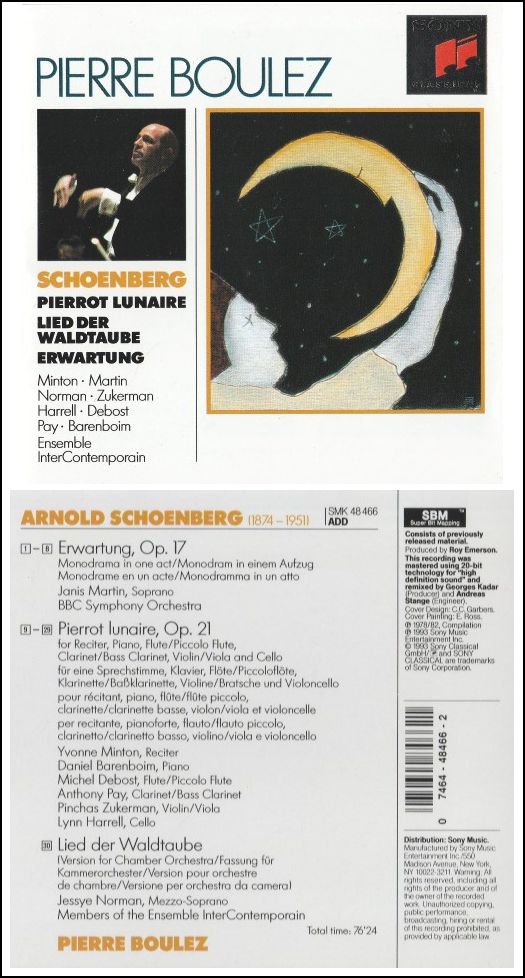

Then I did a crazy staging in Frankfurt with Dohnányi conducting

and Ingvar Wixell was my partner. It was on a double bill with Schoenberg's

Erwartung. I did not do the

Schoenberg -- I had not done it yet, but I've done it lots and lots of

times since then (including a recording shown below-right. Vis-à-vis

that recording, see my interviews with Pierre Boulez, Yvonne Minton, Daniel Barenboim, and

Lynn Harrell.)

But in Frankfurt, the director had me start out on a carousel horse and

the wind was blowing through my hair. I had a white dress with lights

all over it, and each light had a little battery. Later I was in a

field and corn was blowing back and forth. It was just nutty, but

sometimes those kinds of things are fun to do.

BD: Do you

like all this imaginative staging?

JM: It depends

on what you are singing. I wouldn't want to sing my vocally most

taxing roles doing those gymnastics, no.

BD: In Bluebeard, there are just the two characters

onstage for the whole hour.

JM: Yes, it

can be kind of boring if you don't have two strong people. You have

to know exactly all the time what you're going to do.

BD: One of

the great theatrical experiences of my life was at a Chicago Symphony concert

version of that opera. When they opened the fifth door and all that

spectacular brass burst forth...

JM: ...it

would be shattering, yes.

BD: Let's

get back to Wagner. Do you sing your Wagner roles in one or another

translation?

JM: No.

BD: Would

you, if you were asked?

JM: Probably

not. In the early part of my career I did sing a Venus in English,

and vowed then and there never to do anything of Wagner in English again.

BD: You don't

think it works?

JM: It probably

works for the audience, but it doesn't work for me. I don't like

it.

BD: If you

were in the audience would you enjoy it more?

JM: I don't

suppose so because I speak German so fluently, but if I were an American

and did not understand German it would be nice to understand the words.

But translations are usually quite archaic. You can't understand them

anyway, and if you do you laugh.

BD: Of course

Andrew Porter's translation

of the Ring is superb. I saw and heard that in Seattle.

There they did it one week in the original German and the following week

in the English translation. Noel Tyl mentioned to me

about having a memory lapse in the English cycle.

JM: I can

understand that. All of a sudden you don't know which language to

sing it in. You know what you want to say, especially if you're fluent

in both languages. It's criminal to make someone do that -- to go

back and forth. They should do it all in one or the other.

However, in Ariadne, quite often

in America the Prologue is done in English and the opera is in German.

I used to sing the Composer, and it's easier to sing in German, but I think

the audience appreciated having it in English.

BD: Maybe

someday they'll rig up some kind of thing like they have on the television

screen with the running translation in a box on the floor... [Remember, this interview was held in the fall

of 1980, long before supertitles were being used in theaters! Perhaps

I should get credit (and royalties) for my idea... (!)]

JM: And too

bad if the singer is on the floor with her face behind all those words!

In the Manon Lescaut on the TV

from the Met recently, I noticed they were on the ground a lot in the last

act and the words were passing all over their faces.

BD: How about

singing two different roles in a single opera?

JM: Oh my,

I've done lots of roles in lots of operas. This is my 20th anniversary

year in opera. I started so very young and I began in little tiny

parts in San Francisco. I studied there for two years in the Merola

training program but was too young to be in a contest they had out there.

I was 18 and 19 and you had to be 21, but Mr. Adler said that I was

very talented and should come and study there. I learned my first

scenes and saw all the rehearsals -- chorus and orchestra, everything.

BD: Is this

good experience for a young singer to witness these rehearsals?

JM: It was

for me. I was eating it all up. I'd never seen an opera before.

I had quickly learned 3 arias to sing for Mr. Adler. I'd only been

studying voice for 3 months when I auditioned for him. I guess I was

a "natural" at that time. I auditioned for him and then trained with

him for two years, and had a standing room pass to the operas. In

the meantime I was going to the University of California at Berkley.

Then I got my contract for the following season when I jumped in for a girl

who had won the auditions. It was in a television program. She

was in two scenes and I was in two others. I was singing mezzo at

that time, and she got sick the morning of the program. I had learned

all of her things, so I did Suzuki and Maddalena and Martha in Faust and part of the title role of Carmen. It was funny. I was

changing from my Japanese eyes, and to long hair back and forth between

the old gray wig and the regular one. Mr. Adler was announcing the

program and was calling off-stage, "Janis are you ready? Can we go

on?" At the end he was very pleased with the way I had handled everything

and kept my nerves, and offered me a contract for the following season.

That was in 1960 and I got very tiny parts. I was an orphan in Rosenkavalier, and the next season I

sang Annina. Then in Germany I sang Octavian and now I sing the Marschallin,

so I really know Resenkavalier

by now!

BD: Suppose

you were asked to do a recording of Rosenkavalier

and sing all the parts that fit your voice. Would you do some kind

of stunt like that?

JM: I don't

think my voice would be suited for Sophie ever, but it would all sound

the same, wouldn't it? Your voice sounds the same whenever you sing

even when you are a different character. You could try to color it

but everybody'd say, "It's her, I can tell!"

BD: Talking

of many roles, you've sung Venus, but have you ever done Elisabeth?

JM: I've sung

Venus many many times. It was the first part I ever sang in Germany.

I've sung Elisabeth in concert and I'll sing it next year in Germany.

BD: Would

you do both on the same evening?

JM: It can

be done but there's no reason to do it. You can say that it's the different

sides of the character, but you don't have to do it. It can be that

was in Tannhäuser's imagination that it's the two sides of the woman

he likes, but it doesn't have to be the very same person.

BD: Then you get into Wagner's imagination.

BD: Then you get into Wagner's imagination.

JM: Well,

nobody can ask him anymore! He had a wild imagination, I must say;

some of the stories, and his twists of the various legends such as the Ring

that he put into it himself.

BD: What parts

do you sing in the Ring?

JM: I used

to sing Fricka in both operas, but I never did the Götterdämmerung Waltraute.

I've sung two separate Walküren, and Fricka and Sieglinde, so that's

four parts in that opera. In Rheingold

I used to sing Fricka and now I do Freia -- not everywhere, just in my

home theater, the Deutsche Oper in West Berlin. In Siegfried I don't sing anything and in

Götterdämmerung

I used to do a Norn, which is very interesting. I like those parts;

they've very short, very important, and you're through at the beginning

of the opera. Now I sing Gutrune and I'm there the whole evening and

I don't have a bit more to sing. Probably it won't be too long because

everybody's been asking me for years and years, but I'm starting to get

ready to do Brünnhilde. I will be doing my first Isolde in Zurich

in January, and that leads into that direction. But I've always said

that as long as I'm singing Sieglinde I don't want to do Brünnhilde

because nobody will ask to me to Sieglinde anymore, and that happens to

be my very best part of any part I sing. Everybody tells me they

think that's the best thing I've ever sung.

BD: It was

a very satisfying portrayal here.

JM: I feel

very engaged in that opera. I do in most of the parts I sing, unless

it's a part I really can't identify with, and I end up eventually dropping

those roles.

BD: You're

to the point in your career now when you can say "no"?

JM: I've said

"no" for years. I've always been able to say "no" because I've kept

my cool and I've never been so ambitious that I've taken things that I felt

were too much for me.

BD: Is it

hard to say "no"?

JM: Oh, of

course it is because you know if it goes well it might make the difference

as to whether you make a world career or not. I decided that I would

like to take the middle way -- take the big houses and take the parts I'm

offered that I want to do, and if they offer me things that I don't want

to do then I don't do them. Maybe people get angry if you say "no",

but that's too bad because if I feel it's not a part for me then I don't

do it. It takes a lot more strength than to say "yes" all the time.

I think that my voice is much fresher at my age than a lot of others singers

who were much more ambitious. I would not say I'm not ambitious but

I just think about it a little more.

BD: You've

paced your career in such a way as to not burn yourself out. Is this

the kind of advice you'd give to a young singer?

JM: It depends

on the temperament. I know I had a lot of temperament, and if I had

gone right into the repertory I sing now I would have probably sung myself

out because I would not have been able to control myself at a young age.

If you can keep cool about it, it is all right, but if you're too cool

then you don't make it very interesting... and you don't make it either.

If you're cool on stage, that's the bad part. If you're cool when

you're thinking about it and looking at your calendar and being realistic,

that's necessary; knowing that there I'm going to have this much time to

rehearse, and I'll have that much time to get used to the time-change from

the jet-lag, and then there will be that many days for a new role, that

many days to feel comfortable with it, who's the conductor going to be,

who's my partner going to be, etc. There are certain stage directors

who are so taxing that you come crawling out for the first performance,

so I try not to work with them too much.

BD: Do you

prefer doing new productions and premieres as opposed to a set show?

JM: It depends

on how much time I have. If it's a big new production in an important

house, then you take the time for it. I don't like to work with people

who upset me and have ideas that go against my convictions. I'm rather

traditional. I like new ideas and I am very excited to be able to

talk to a stage director about them, but I don't like to be forced to do

things that I feel are absolutely wrong.

BD: Have you

pulled out of a production in the middle of rehearsals because of disagreements?

JM: Not in

the middle, but one time it was very close to the beginning. I must

say I'm rather consequential and I'm not hard to get along with, but I don't

accept everything that is thrown at me. There are some things that

are incredible that you can't say yes to if you have any character.

* *

* * *

BD: Tell us

a little about the characters you've portrayed. You're doing Ortrud

here in Chicago. Will you eventually do Elsa?

JM: I don't

think so because I don't think anybody's going to think of me as Elsa.

I have rather a light-colored voice for Ortrud, but I don't believe Ortrud's

a mezzo. I never have believed it. Astrid Varnay was probably

the best Ortrud that ever lived, and she was never a mezzo. Ortrud

needs such a strong high voice, and there are only a couple of places in

a couple of ensembles where it's low. The rest of it is very declamatory

and very high.

BD: Do you find it easy to be menacing?

BD: Do you find it easy to be menacing?

JM: Well,

I'm such a nice person really... Actually, it's funny. The people

who are the nicest find it easier to be menacing on stage than some people

who are really conniving and terrible. I guess maybe they don't want

to show their true character. Ortrud is not a very nice lady, but she's

convinced that she's right in what she's doing.

BD: Is she

the power rather than Telramund?

JM: Actually

I think Telramund is rather in the hands of Ortrud. She puts the things

in his mind to make him think, "Oh yes, I must do this and that."

He is continually looking to Ortrud, "Am I doing this right?" He relies

on her to give him advice, and when she gives advice to fight against Lohengrin

and he loses, he says, "It's all your fault. You told me to do this."

But then I tell him also to plant this idea in Elsa's mind to ask Lohengrin

his name and where he comes from. I do it myself, too. So he's

a little bit of a puppet, or a marionette under Ortrud's power. She's

more of a force then he is. He has to be strong on stage, but he

is the weaker of the two. I don't think he really realizes just how

bad she is.

BD: How would

you feel if, at the end of a performance, the audience was hissing and booing

for the two of you?

JM: I would

not take that as a compliment, but when we are getting into position before

the curtain rises, the chorus will start to hiss and we have a big laugh

before we get going.

BD: Are you

distracted by extraneous things before or during a performance?

JM: I try

to detach myself completely from anything personal while I'm on stage, starting

from just before I step on stage. Five minutes before you go on, you

need to blank out anything else because you need a tremendous amount of concentration

onstage. I find it terribly distracting to have things like noises

from the wings and flies, or doors opening backstage so you hear the faint

sounds of others away from the performance. In Berlin the stage hands

have little walkie-talkies and you can sometimes hear that, or hear some

feedback from there. Things like that jolt me -- nobody else notices

it, but it irritates me tremendously, because it breaks my concentration.

It makes me angry that people are not more considerate of the performance

that's going on, since that's the most important thing happening in the

house that night.

BD: Does the

conductor waving his baton bother you?

JM: Well,

he's part of the performance, but I don't always look! One night

there was a man in the first row, right to the side of the conductor, and

he was reading his program with a little flashlight! This annoyed

me a lot. I wanted to stop the performance and tell him to put it

out! It was driving me crazy!

BD: Vickers

scolded the audience once.

JM: Well,

I'm not Vickers, and I didn't want to distract the whole audience.

If I am distracted, I would not want the whole audience distracted.

I love Jon, but I don't understand how he could do that, and I could not

do that myself.

BD: How much

do you rely on the conductor?

JM: Everything

has to stay together, that's for sure. He's not a machine and some

nights he's a little faster or slower. It can be a problem if he doesn't

catch it right away when you want to go faster because he happens to be

slower that night, or because you have phlegm in your throat or have to

swallow one more time or are a little short of breath or whatever.

BD: Do you

find the good conductors are singing with you?

JM: Yes!

The very best are. There are a lot of good conductors who are not

always concentrating on the singers because they feel they can rely on certain

people. They feel they can let them go and concentrate on the orchestra,

and I happen to be one of those people they sort of let go. I don't

have really low performances. If I don't feel well, then I cancel,

and that is one thing I've always done... unless there's no other way for

the theater to get somebody else at the last minute, if you get sick at the

last minute.

BD: So there

are no times when the manager comes out to announce your indisposition?

JM: There

was one time I had a cold and thought it was over. I had taken some

strong medicine and the doctor said I could go on, and I did, but during

the second act my voice kept getting smaller and smaller. The conductor

said he didn't notice a thing, but I said somebody should go out and make

an announcement before the last act. If I don't make it through the

last act, it's too late after it's over to say anything. I did sort

of scrape through, but it was not the kind of performance I like to give.

It was Meistersinger, and the most

important things that Eva sings are in the last act. You just die

up there if you're not feeling well, and my vocal cords were swelling and

I couldn't do anything about it. I had to keep taking more breaths

because my air was escaping.

BD: Did that

break up the line?

JM: Well,

if you're as experienced as I am you can fool a lot of people. I don't

like to fool them, but if you're in trouble you have to sometimes.

BD: Those

are the times you rely heavily on technique.

JM: You must

or you might hurt your throat, and that's your capitol, your whole life,

your career. You must not damage your vocal cords.

BD: I've been

at performances where they announce an indisposition and the singer sounds

glorious.

JM: They feel more relieved. It's all psychological.

There are ways of thinking about that. One can tell the audience

that you're indisposed, and then they're grateful that you've done the

performance and gotten through it. Sometimes they're listening for

a little something they might not have heard otherwise, and they say, "Oh

yes, you could certainly hear she was indisposed." Last December

I did my first Marschallin. The first performance I sang with a cold,

and the second one I wondered if I'd ever get through it at all. The

doctor wouldn't guarantee for it, but said 90%, and I felt well enough...

BD: Of course

you have the long break because you do not sing in the second act.

JM: Yes, but

that's exactly when your voice can drop. If you keep going and keep

singing and singing, it might drop at the end of the performance. But

if you sing the first act and then it drops before you have the third act

to do, it's too late to stop before the trio and say you're not feeling well.

So I had an announcement made, but I thought that second performance was

better than the first one, so you never know.

BD: Do you

read the critics?

JM: We have

a little system in our house. My husband reads them, and if they're

good he shows them to me. If they're not, he doesn't say anything

about them. I want to read them anyway, but not before the second

performance because you find yourself being influenced by them. You're

a little bit excited and roughed up a bit before the performance to read

something that may not be even true, but it may make you wonder about something

you've done and there's no time to really think about it. So I don't

read them just before a performance, I read them sometime when I can be objective

about them. I must say I haven't had a bad critic for years [knocks

on the wooden table]. I joked about it the other day saying the good

reviews go in an album and the bad ones go in the wastebasket. It's

just one person's opinion, and everybody has a different opinion -- even the

critics. They have their problems, too. They might have been working

hard all day, or eaten too much or not eaten anything, or just had a fight

with their wives or whatever.

* *

* * *

BD: Do you

like singing the long parts? You're into Wagner and these are the very

long and arduous parts. Do you like these as well as shorter ones?

JM: It's a

hard question to answer. I don't like them because they're long, they

happen to be long and I happen to love some of those parts. I would

prefer to have some shorter parts, and I'm hoping maybe in the future to

have a few that are shorter because at the moment all of mine are just killers.

There are none where I can go in and say, "Tonight I have an easy evening."

One of my easiest evenings would be a hard one for anyone else. In

my theater in Berlin, they asked if I wouldn't like to have an easy evening

and do the mother in Hansel and Gretel.

Actually, I'd rather do the witch ... [laughs] My son would love it.

BD: Do you

like all the parts that you sing? Are you sympathetic with the characters,

or are there some that lie well for the voice but you don't like the character?

JM: I do not

like Venus, and I've done Venus probably more than any other single part

in my repertory. It is not written very sympathetically for the character,

and consequently for the person singing it. She should be seductive

and she has no chance at all to be seductive -- at least in the Dresden

version.

BD: Do you

prefer the Paris version?

JM: I did

that first, and they still do that version in Vienna -- an old Von Karajan

staging of it with terribly old costumes and wigs. It's probably

one of the few places outside of Paris that they do that version.

The Parisians feel it's their version. That version is longer but

easier for me. It's more singable, more seductive, so you can understand

how he was there in the first place. In the Dresden version, the

minute she opens her mouth she's screaming at him all the time, being sort

of nasty to him all the time.

BD: But

you convey this nastiness?

JM: I do,

but if someone asks me if I like the part I cannot honestly say that I like

singing it.

BD: Are there

roles that you want to sing that are not in your voice?

JM: I suppose

some of the Italian, Verdi roles. I never really thought about roles

that are not for my voice. I'm not an Aïda, I'm not a Traviata.

I would like to sing Manon Lescaut and have not done it yet. I would

also like to sing Santuzza. In Europe that's done a lot by a soprano.

It needs a good middle and lower range, which I have from the days I was

a mezzo. I need that for Ariadne and Sieglinde and other parts in

the soprano repertoire.

BD: How did

you arrive at the decision to go from mezzo roles to soprano roles?

JM: My voice

made a gradual change as I matured. When I went to Germany I was 26

years old and I had not yet sung a big part. That's the reason I went

there. I went to Nuremberg to get my repertory, and through singing

Amneris, Eboli, Dorabella, the Composer, Octavian, and Cherubino I found

that I was the best in the high parts. One of my best parts used to

be Eboli, although some of it was too low for me. In all the parts where

most of the mezzos would die because of the high range, that's where I would

shine. The Composer is very high, and Octavian is not very low, and

people and critics were writing that perhaps I was becoming a soprano --

which in fact, I was. It was a gradual, natural thing. I didn't

just decide; it happened to me.

BD: There

are some mezzos today who are trying to push their voices up to soprano.

JM: I don't

know whey they don't just try to be what they are.

BD: Because

they want to sing Tosca?

JM: Tosca

is a fantastic part, I must say, but you can't push yourself into something

you're not. Eventually you pay for it. You have to find out what

you can sing and what you can't.

BD: This is

the patience that you have which is all too rare.

JM: I don't

know if it's patience. I certainly try things out before I say that

I'm going to do them.

BD: When you

approach a new role, what steps to you take?

JM: I get

the score and I look at the music and at the words. I look at the

type of character and the kind of singing that's going to have to be done,

and the range -- whether there is a lot of piano in the high portions. That's

why I would not do Aïda, because although I have a good high voice,

I don't have the kind of voice that can keep singing piano with great relaxation in the top.

That takes more lyricism, and I have a more dramatic voice. I think

the parts I sing suit me physically and vocally. There are a few roles

that would suit me very well -- I could sing Octavian perfectly well --

but nobody's going to engage me to sing them, so why would I try to sing

them? I must be realistic about it. I'm smart enough to know

that nobody's going to think of me as that character. I would love to

sing Desdemona, but nobody's going to engage me to sing that. People

think of me in the Wagner/Strauss roles. In a way it's too bad, but

in a way it's good because it's the roles I do sing the best.

BD: What about

making recordings of a few of those roles that you would not do on the

stage?

JM: As a matter

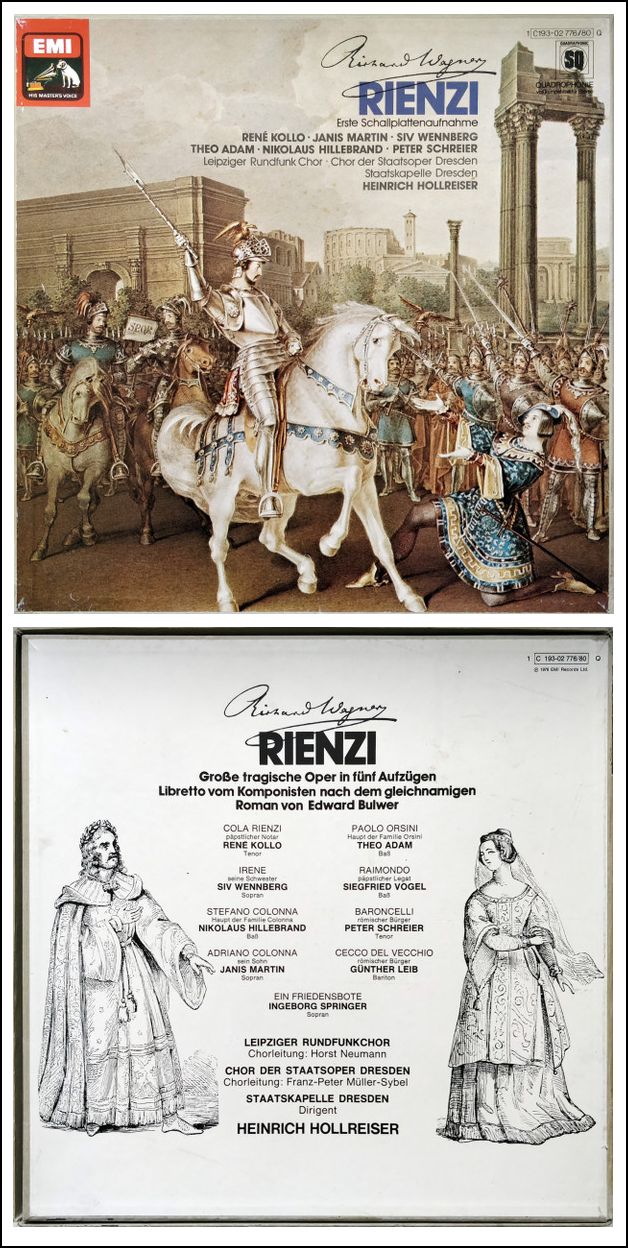

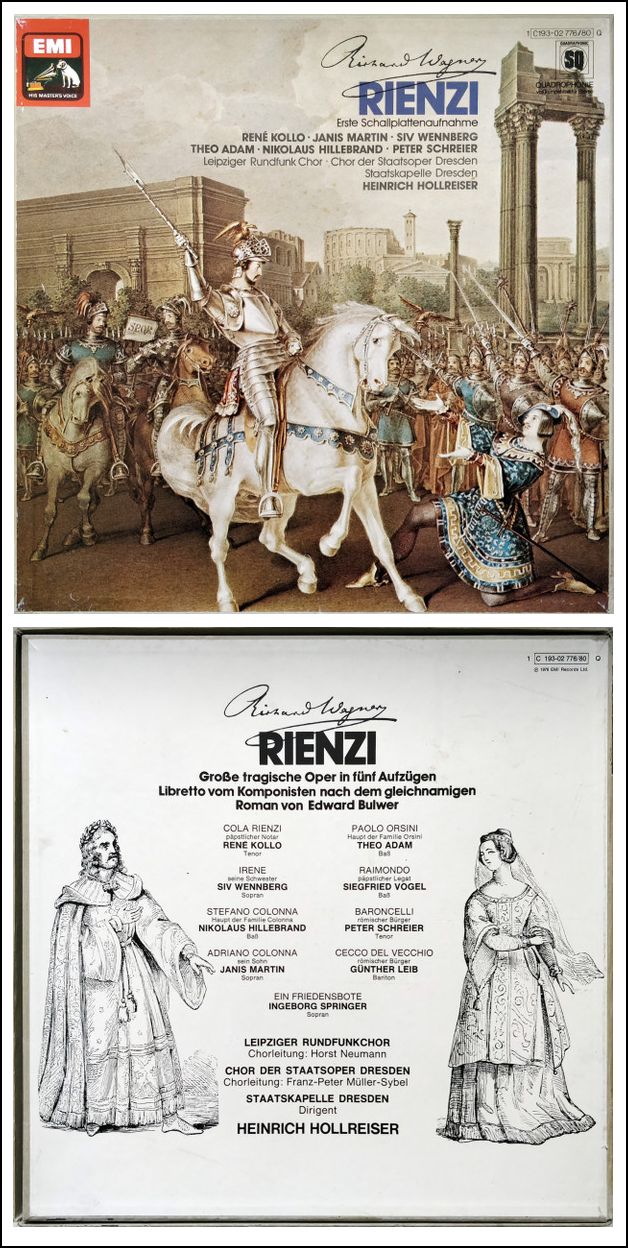

of fact I did Adriano in Reinzi,

and I would never, ever sing it on stage. (Recording is shown below-left.)

I had a series of concerts in Berlin and Vienna and the house just

went wild, but I wouldn't want to do a lot of fencing and protecting my

girlfriend. Being a knight in shining armor just doesn't suit me,

although it's a beautiful part to sing. It's very taxing, very hard.

BD: How did

you approach Octavian, then, when you were singing it? You've got

to be a young man.

JM: I was

a young woman, and it is written for a woman, so you don't really have

to be a man. You're a young person. I was very arduous in a

way that I could make it believable. I was quite slender then.

Most people are surprised to see how short I am. I think big!

I have a certain carriage and I do it on purpose. I know why I am

doing it. I do try to wear comfortable high shoes to make myself look

a little bit taller.

BD: What about

modern repertoire? You do some Berg...

JM: The only

Berg opera I've ever done is Wozzeck.

I wouldn't do Lulu. That wouldn't suit me, anyway. The only

other new work I do is Erwartung

of Schoenberg. That's 30 or 35 minutes of just one person, a monodrama.

It's very taxing and very hard. When I first started I thought I would

never ever get it learned right. It's just something that's incredible.

BD: What if

a young composer wants to write something for you and asks for advice?

JM: I'd say

to finish it first and let me see it. It would have to be someone

who knew my voice while composing it. I wouldn't just say, "Oh fine,

I'm thrilled." I would ask if he knew what I can and cannot do, and

what I do the best and what I don't do the best. It would have to be

someone who was writing it with me in mind, knowing what I can do and what

I sound best doing. It wasn't written for me, but I was offered a part

for a record in Milan recently while I was there doing Erwartung with Abbado at La Scala.

I was shown the score, but I knew before I was saw it that I wasn't going

to do it because I know what this composer writes like. It's been

done, but never recorded. I looked at it and thought, "My God, how

could anybody want to do that?" It had me humming a high C with the

mouth closed and slowing opening the mouth. Maybe somebody will say

yes to that, but it's not going to be me.

BD: Are there

any composers today who write in a style grateful to the voice?

JM: Probably

you're asking the wrong person because I don't know too much about it.

In the time I was at the Met we were doing Vanessa. Barber, Britten and Menotti

are the three that come to my mind that I think write beautifully for the

voice.

* *

* * *

BD: Are you

good audience?

JM: Yes, at

something that I don't have a part in or don't sing. Watching an

opera that I have a part in, I can't sit still. Everybody does it

differently. I know all the mistakes and I think, "Oh isn't that

terrible," or "Oh, I wish I could do it like that." I'm a good audience

if I have the nerves for it and have the time. I don't go to a lot

of opera, though. I go to other things. I like to go to musicals

and the ballet and symphony concerts.

BD: Straight

plays?

JM: Mm-hmm,

a lot.

BD: Would

we find you at a disco?

JM: No, it's

too loud for me. I'm used to having the orchestra in front of me, but

not that way.

BD: Speaking

of things in front of you, do you like working with a scrim?

JM: It's good

for the lighting but it's terrible for us. We can hardly see the conductor

sometimes. In this Lohengrin

in Chicago there are two scrims, and you feel like you're singing into a

paper bag.

BD: The overall

impression comes across to the audience very well, however.

JM: Oh I know

it does. I'm not worried about it. It's good for certain lighting

effects, but sometimes I wonder why they're using it because certain effects

are not very effective. The visual effect is very important.

BD: Are there

times when you go to the director with an idea to try?

JM: Only in

things I'm doing myself. I don't give hints on how to stage the opera

in any way. If he's told me to do something and I don't feel that

it's right, or if I feel I can't do it yet, I ask him to explain it to me

in another way and then I try it a couple of times. If I can't do it

properly and with conviction, then I say to give me another day or two to

work it out, or eventually ask him to do something else there. I ask

if we could find another way to express the same thing.

BD: What if

you got a really good idea for another character? Would you ask the

director to try it?

JM: I'd probably

talk to my colleague first and see if he thought it was a good idea.

Sometimes you can offer the stage director something that works because

the two characters have already gotten together on it.

BD: Have there

ever been directors who have left you too much on your own to come up with

ideas for your character?

JM: Absolutely.

There was a problem at La Scala recently. Abbado, who was conducting

Erwartung, wanted to do all the

staging that Schoenberg had written into the score. There are only

about ten things he wrote there, and it's usually when there is not very

dramatic singing -- things to the side which are not very important to the

action, actually. He wanted somebody to stage it, but the person did

not want to do what was in the score, so it was up to me. Then they

gave me a very unfortunate dress. It was by a very famous designer,

and everybody was so impressed that I was going to get this beautiful dress

from him. I thought it was just awful, and so did the critics.

They said it was too bad that this dress was designed for this opera, and

the poor lady sang so beautifully and had to wear this horrible thing.

It distracted rather than helped. I saw that from the very beginning,

but everybody was so impressed with the designer's name. I'm not impressed

by that very much. So I had to do the staging myself. I asked

for this and that, and the director gave me those two things on an empty

stage. The rest of it was flat with nothing on it, with the projections

that Schoenberg had used, and they just didn't work, that's all. I

thought it was miserable, but the main thing was the music and we got that

over.

BD: Is that

the way it is in opera -- that the main thing is the music?

JM: In this

case the main thing is the dramatic impact of the music and the dramatic

impact of the one person, no matter what is surrounding her. If the

personality of the one person in this work does not come through, you might

just as well forget it because there's nothing left to it. Nobody

can help you.

BD: What about

in a larger work like Meistersinger

or some others?

JM: Then there

are lots of people, and each does his own thing and relies on the others

to do theirs. Then they get together on it.

BD: In a way

I'm asking the "Capriccio" question -- is the music the servant of the words

or vice versa?

JM: I don't

think you can separate them at all.

BD: Do you

enjoy doing recordings?

JM: It depends

on the conditions. If they're done too hastily without a chance to

repeat things and do them well and be relaxed about them, then I don't

enjoy it. The Rienzi was

quite satisfying and I did enjoy it. We had lots of time for it, and

that was nice. (See my interview with Peter Schreier.)

BD: I'm looking

for your thoughts on the put-together perfect-performance that emerges

on the plastic disc.

JM: It's hard

on the live performance because people sit at home and listen to the "perfect"

performance. They're almost dead performances because they don't

have any imperfections in them -- at least they shouldn't. Sometimes

they do because they've been made too hastily and not heard well enough

before they've been released. Then the audience goes to a live performance,

and somebody stubs their toe or something distracts the audience and they

say they'd rather listen to their recording. But then that's not

realistic because you have a completely different kind of acoustic in a

live theater and you also have this chance of something going a little

bit wrong -- which is interesting I think. It's the live performance

with the personal things about it...

BD: It has

more soul?

JM: It does.

You just can't compare them. I'm much more for the live performance

than for the recording. I think things should be recorded so you

have them forever and you can listen to them at your leisure. Why

shouldn't you have recordings as well as the live performances? I'm

for both, but it's not so good to compare the two.

BD: What about

TV and films?

JM: It can

bring people closer to the opera -- especially those with subtitles -- and

brings opera to people who might not ever have a chance to see an opera otherwise.

I think it's good.

BD: It should

stand alongside, but not be a substitute?

JM: Oh, hardly

a substitute.

* *

* * *

BD: I want

to ask you a bit about Isolde. You're just coming to this part, so

tell us a little about the Irish princess.

JM: She gets to use a lot of the things I've

learned though many years of singing. She's very angry at the beginning

with Tristan, and she gets to be ecstatic in the love duet and then sort

of mystic and mythical at the very end. I can see myself using a lot

of the experience I've had from many parts I've sung. I'll need a lot

of the good middle range that I've had in the mezzo parts and a lot of the

good high range and a lot of the experience I've had from singing Wagner.

JM: She gets to use a lot of the things I've

learned though many years of singing. She's very angry at the beginning

with Tristan, and she gets to be ecstatic in the love duet and then sort

of mystic and mythical at the very end. I can see myself using a lot

of the experience I've had from many parts I've sung. I'll need a lot

of the good middle range that I've had in the mezzo parts and a lot of the

good high range and a lot of the experience I've had from singing Wagner.

BD: You have

done many performances as Brangäne...

JM: Yes, as

a matter of fact that was the last mezzo part I ever did, and I did it with

Birgit Nilsson in 1969 or 70.

BD: Will you

wipe out the one part when you sing the other?

JM: Yes.

I've really not done it in 10 years. I remember having done it and

I remember the words she sang and the music she sang, but it's not going

to interfere at all. I've never had any trouble weeding out one part

from the other -- like the Marschallin and Octavian. I was a little

worried about Eva and Magdalena in Meistersinger

because they have all that pitter-patter dialogue singing, but nothing

ever happened. I would always warn the mezzo not to make any mistakes

because then I'd ask the question and answer it, too. [Both laugh]

BD: What about

the end of Tristan? How

do you see this transfiguration -- is it mystical?

JM: It's not

mystical, but it shows a person who has gone through the span of life in

a very short time -- from the child she was at the beginning, she's the mature

woman at the end who knows. She's sort of wise and all knowing.

I've not done it yet so it is really too early to ask me. I'm right

in the middle of studying it now.

BD: Is it

something you're really looking forward to?

JM: Oh, very

much. It's the longest part I've ever done in my whole life -- it's

probably one of the longest in the repertory, and the most taxing, probably.

BD: We've

not touched on the Dutchman, which

you sang here and recorded with the Chicago Symphony and Solti. Do

you find that she goes through the same kind of thing as Isolde only in a

shorter time span -- from the innocent to the mature?

JM: No, I

think Senta is a much different character. She's the dreamer.

She's looking for someone she's not even sure was even real or that she

would ever see. Isolde is dealing with a person she fell in love with.

He killed her fiancée and sent her the fiancée's head, and

she still fell in love with him. Tristan's really a pretty miserable

character when you think about it. So she's dealing with a real person

and Senta is dreaming about this picture and the story she's heard.

BD: Is Senta

really surprised when the Dutchman actually arrives?

JM: I think

deep down she knows he exists, but doesn't expect him to be standing in

her doorway.

BD: What would

she have done if he had picked one of the other girls who were spinning?

JM: [Laughs]

That's a good question. I don't know! They're not so interested

in him. They probably would have all run away. They all know

the story, but there's a bond between those two electric poles.

BD: What about

Kundry?

JM: I do that

one all the time. Around Easter time I could do ten Kundrys in ten

days if I'd let myself. Vienna, Munich and Berlin all do productions

at the same time, and it's a part I've gotten so well known for that I get

asked by everyone to do it. I never can say "yes" to everyone, so somebody's

always angry and you can't help it. Sometimes I split myself between

two, but not more. Last year I did Vienna and Berlin, and the previous

year I did Munich and Berlin. It's just different each year.

You can't do everything.

BD: Tell us

about Kundry.

JM: She's

fascinating. She's in a different state in the different acts.

In the first act she's not being possessed by Klingsor. It's when

he pulls her with his magnetism towards the end of the first act when she's

going to sleep. She says she must sleep and asks that no one come

near her. Then he takes possession of her, and all her actions toward

trying to seduce Parsifal are under the influence of Klingsor. It's

not what she wants to be; it's what she has to be.

BD: Is it

her mind that is under his power or her soul?

JM: I don't

know... Can you separate your mind and soul in an opera character?

It's hard to say. She must do it for whatever reason. She's

compelled to do it; he makes her do it. She doesn't want to do it.

She wants to be good. She says to Gurnemanz, "I never can be good.

I'm terrible. Don't thank me for anything." She doesn't want

anybody to be nice to her because she feels terrible. She feels guilty

although she doesn't know what she's done.

BD: Is it

almost like a hypnotic state?

JM: Yes.

Then at the beginning of the second act with Klingsor she's miserable,

absolutely miserable. She's trying to fight him off and he's stronger

than she is. Then he takes possession of her and wins her over, and

she starts laughing and becomes hysterical.

BD: How does

the laugh and the scream affect the voice?

JM: I've learned

how to do them without hurting myself at all. The first time I thought

I was going to strangle myself. You have to support it like a high

G and let your voice come down like a waterfall -- at least that's how I

do it. You must never just scream. You have to support like mad,

otherwise you could hurt yourself.

BD: Do you

enjoy the third act where you only sing a couple of words?

JM: Very much.

It is the most rewarding thing, although you must get calmed down and quiet

enough to do that third act. It's simply an acting part. It's

just beautiful and I just love it.

* *

* * *

BD: Now you're

looking toward Brünnhilde?

JM: Well,

everyone else is looking toward it for me! I've said "no" up to now,

but....

BD: Would

you be able to do just one and not the other two?

JM: That's

the thing. Once you start doing one, then everybody wants you to do

all of them.

BD: Would

you be happy doing just one of them?

JM:

I would like to do the Walküre,

but most people think of me in Götterdämmerung.

Siegfried is the shortest but probably

the hardest. You have the whole day not knowing what to do with yourself

because you have a hard performance, but it's so very late that evening

and the tenor is nearly dead by that time. People think she's got

it easy but she doesn't. She has to come in there and be fresh and

not worried, and that's hard.

BD: Do matinee

performances bother you?

JM: I draw

the curtains and pretend it's later. The voice is different at that

time of day; our bodies are geared for evening work. We're used to

getting up late and having something to eat, and then exercising or resting

and then going to a performance.

BD: What about

going from one side of the world to the other?

JM: I try,

now, not to sing immediately after I get somewhere. When I went to

Japan last February, I stopped over in Anchorage first for two days to break

up the trip, and then went on to Tokyo. Then I was there about a whole

week before I sang. I gave myself the luxury of having a whole week

before and a week after so that I could get used to the time change, then

have my rehearsals, then the concert, then a week after for myself to enjoy

seeing a little of Japan. It's not every day you can go to Japan.

BD: Is going

from East to West easier than going from West to East?

JM: It depends

on whether you've just packed your suitcase and rushed off with hardly

any sleep or not both ways. Sometimes you're a victim and other times

you can plan a little bit better.

BD:

I trust you enjoy singing!

JM: Oh I do.

I must admit that. It's a great part of my life. I love sports

and I love to swim, but my family and my singing are the most important

things to me in my life. Sometimes it's very hard to co-ordinate the

two, especially traveling around. I have a little boy who will be seven

in two days. We live in Germany. He was born there and is being

brought up bi-cultural and bi-lingual. He goes to the John F. Kennedy Schule, a German-American

school.

BD: So how

do you bring your youngster to opera?

JM: In our

case it's quite interesting. My husband started a boys choir thirty-three

years ago in West Berlin, in the ruins of the city. He had gone to

the musik hochschule and studied

instruments. He wanted to do something, but after the war what was

he going to do? He took little boys from the street, with the patches

sewn on their trousers and their shirts, and had them sing for the grandmothers

and the wounded. Through the years they have made many recordings

and gone all over the world and been to the World's Fair and on TV.

They are the Schöneberger Sängerknaben

[named after the District of Schöneberg in Berlin]. They have

also sung at the Deutsche Oper in many operas that need children.

These days he has children of the first group of boys! That's quite

an accomplishment to have started that out in those times without any government

support and continue for all these years. Anyway, they sing in Hansel and Gretel, and that was the first

thing my son saw at the opera. He went backstage afterward and saw

where the angels had been kneeling down and the tree that Hansel and Gretel

went to sleep under. He was fascinated by it all. He doesn't

like to go to rehearsals; he just likes to see the finished product.

He hasn't gotten that far that he wants to see the repetition. But

I can't take him to all the things I'm in. They're too long, or I'm

killing somebody, or they're killing me, or I'm jumping off somewhere.

In the Flying Dutchman I kill myself

in the end, and in Tosca I kill

the baritone and then kill myself and the tenor gets shot. He's still

a little young for that when it's Mommy, but he is getting so he can take

it in other works. There are lots of theater mothers, but I'm not too

ambitious about forcing my child into that.

BD: If he

goes in that direction, will you encourage him?

JM: I would

rather hope that he does not want to become a singer. Unless you

become someone very, very famous, it's a very difficult job for a man.

You can land at the very bottom or not very much above it, eating your

heart out because you didn't make it. If you don't have something

to fall back on it's a miserable profession. If you make it to some

degree and you're satisfied with what you've done, then it's OK, but what

can a singer do if you can't get a job and can't sing? You're not

prepared for anything else. It's too young for my son yet, but he's

said he wants to be a veterinarian and an astronaut, so who knows what

he will be? But I would like to have him trained to do something

that's useful and needed at the time that he's going to be grown up.

BD: If nothing

else, he will be a good audience!

JM: He will

be a good audience, and he has a gorgeous voice. I could imagine

he would want to be a singer, but he has said he'd rather be a conductor.

[Both laugh] He's definitely a leader. He stages all the games

you play with him, and tells you what to say and where to stand. I

might imagine him as a stage director...

BD: But despite

the difficulties, you enjoy your own career!

JM: Very much!

You know what I hope never happens to me is that I sing just for money.

I like to make a good salary because I have to live, but I never want to

go on the stage having the feeling that this is a job. It's a performance

for me every time I step on the stage no matter where I am. It's

an experience for me and I hope it is for the audience. I don't know

what will happen when I get too old to sing these parts, but I'm not too

worried about that.

BD: Might

you then sing smaller character parts?

JM: Someone

I admire is Martha Mödl,

and she's done that. I don't know whether it's out of necessity

or if she just would collapse if she didn't sing.

BD: There

seems to be a German tradition of leading singers doing small roles as

they get older. This brings their huge experience to the younger

colleagues. Paul Schöffler did that as I recall.

JM: It depends

what kind of singer you are. Martha Mödl can do that because

there are interesting parts for her, but for someone who has sung soubrette

all their life, what can an old soubrette sing? There just aren't

any parts for an old soubrette. Astrid Varnay is another who has done

some interesting parts later on. That might be what happens to me

because I tend to go for the interesting parts anyway. I love the interesting

characters. I do Marie in Wozzeck

because she's an interesting and complex character. She's heartwarming

and tragic. She is wonderful. Tosca has everything a woman

would want from a part -- glamour and love and hate and violence.

I can see why people would want to give up everything else just to sing

Tosca. I suppose I'm able to be more grateful to be an opera singer

now that I'm a little bit older. When you are a beginner, you're

just more anxious to get going and get your career on its feet. When

I left the Met I was still singing small parts, and I made up my mind I

wanted to sing big parts. This is how much I think about things before

I do them. When I went to Germany, I secretly said to myself -- I

don't think I ever said it in words -- if I don't make it at least to some

degree within two years, then I am going to give up completely and do something

else. By the time I'd been there for three months, I'd already sung

Venus in the Paris Version of Tannhäuser

in Paris! I was under contract to a smaller theater, but I guested

in Paris. I also sang Venus at La Scala. I'm grateful to have

sung it because it's taken me so many different places, but I still don't

have to say I like it.

BD: Thank

you so very much for taking the time to speak with me.

JM: You're welcome.

===== =====

===== ===== =====

===== =====

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

===== ===== =====

===== ===== =====

=====

© 1980 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in the studios of WNIB, Chicago, on

October 16, 1980. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, 1994 and

1999. The transcription was made and much of it was published in

Wagner News in April, 1981, and

in Opera Scene in October, 1982.

It was re-edited and the complete interview was posted on this website

in March of 2014. A few more pictures and links were added when it

was updated in 2024.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these

interviews for print, as well as a few

other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce

Duffie was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until its final

moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have

also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his

broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are

invited to visit his website for more

information about his work,

including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of

his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information

about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field

more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

BD: Then you get into Wagner's imagination.

BD: Then you get into Wagner's imagination. BD: Do you find it easy to be menacing?

BD: Do you find it easy to be menacing?

JM: She gets to use a lot of the things I've

learned though many years of singing. She's very angry at the beginning

with Tristan, and she gets to be ecstatic in the love duet and then sort

of mystic and mythical at the very end. I can see myself using a lot

of the experience I've had from many parts I've sung. I'll need a lot

of the good middle range that I've had in the mezzo parts and a lot of the

good high range and a lot of the experience I've had from singing Wagner.

JM: She gets to use a lot of the things I've

learned though many years of singing. She's very angry at the beginning

with Tristan, and she gets to be ecstatic in the love duet and then sort

of mystic and mythical at the very end. I can see myself using a lot

of the experience I've had from many parts I've sung. I'll need a lot

of the good middle range that I've had in the mezzo parts and a lot of the

good high range and a lot of the experience I've had from singing Wagner.