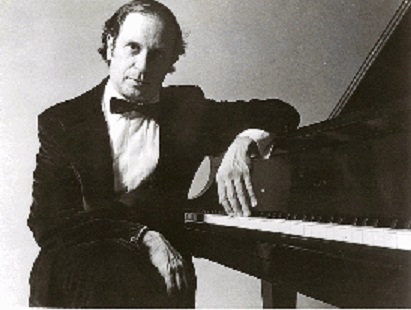

Pianist Alan Mandel

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Mandel, Alan (Roger), gifted American pianist

and teacher, was born in New York on July 17, 1935. He began taking

piano lessons with Hedy Spielter at the incredible underage of 3-1/2,

and continued under her pianistic care until he was 17. In 1953 he entered

the class of Rosina Lhévinne at the Juilliard School of Music (B.S.,

1956; M.S., 1957), and later took private lessons with Leonard Shure (1957–60).

In 1961 he obtained a Fulbright fellowship and went to Salzburg, where

he studied advanced composition with Henze (diplomas in composition

and piano, 1962). He completed his training at the Accademia Monteverdi

in Bolzano (diploma, 1963).

He made his debut at Town Hall in New York in 1948. In later years, he

acquired distinction as a pianist willing to explore the lesser-known

areas of the repertoire, from early American music to contemporary scores.

He taught piano at Pennsylvania State University (1963–66), was head

of the piano dept. at the American University in Washington, D.C. (from

1966). He founded the Washington (D.C.) Music Ensemble (1980) with the

aim of presenting modern music of different nations.

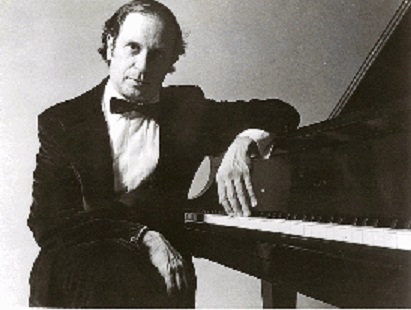

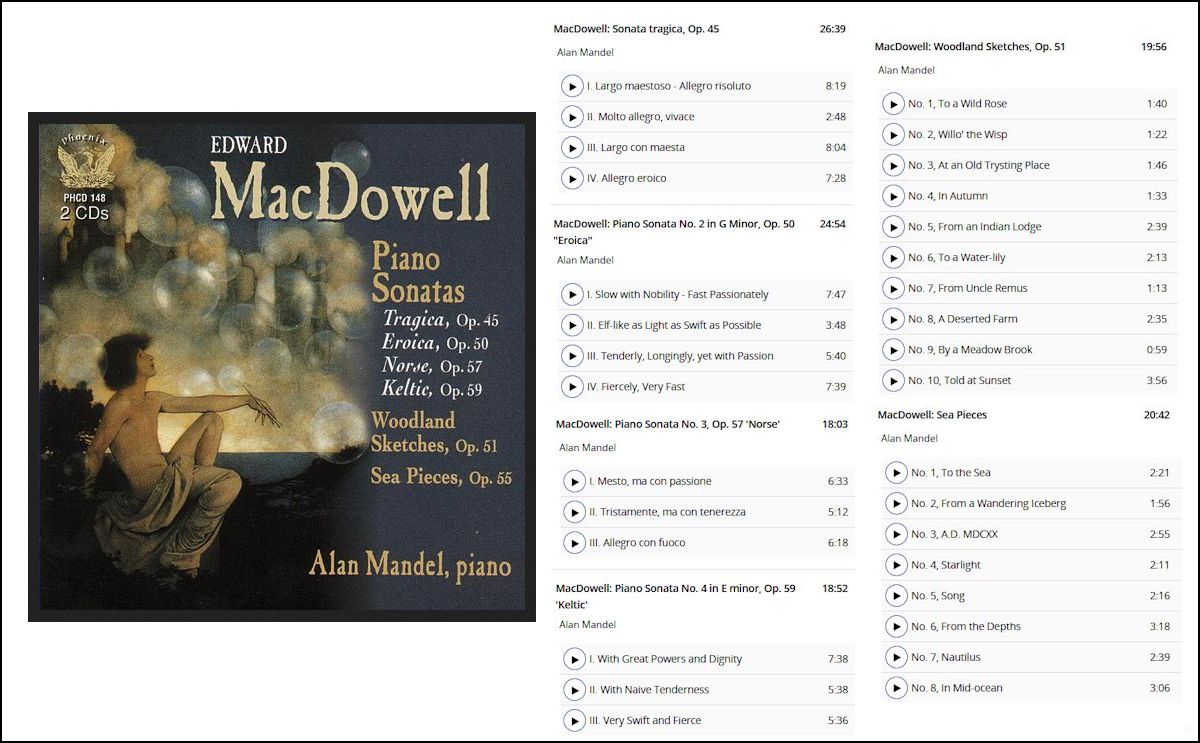

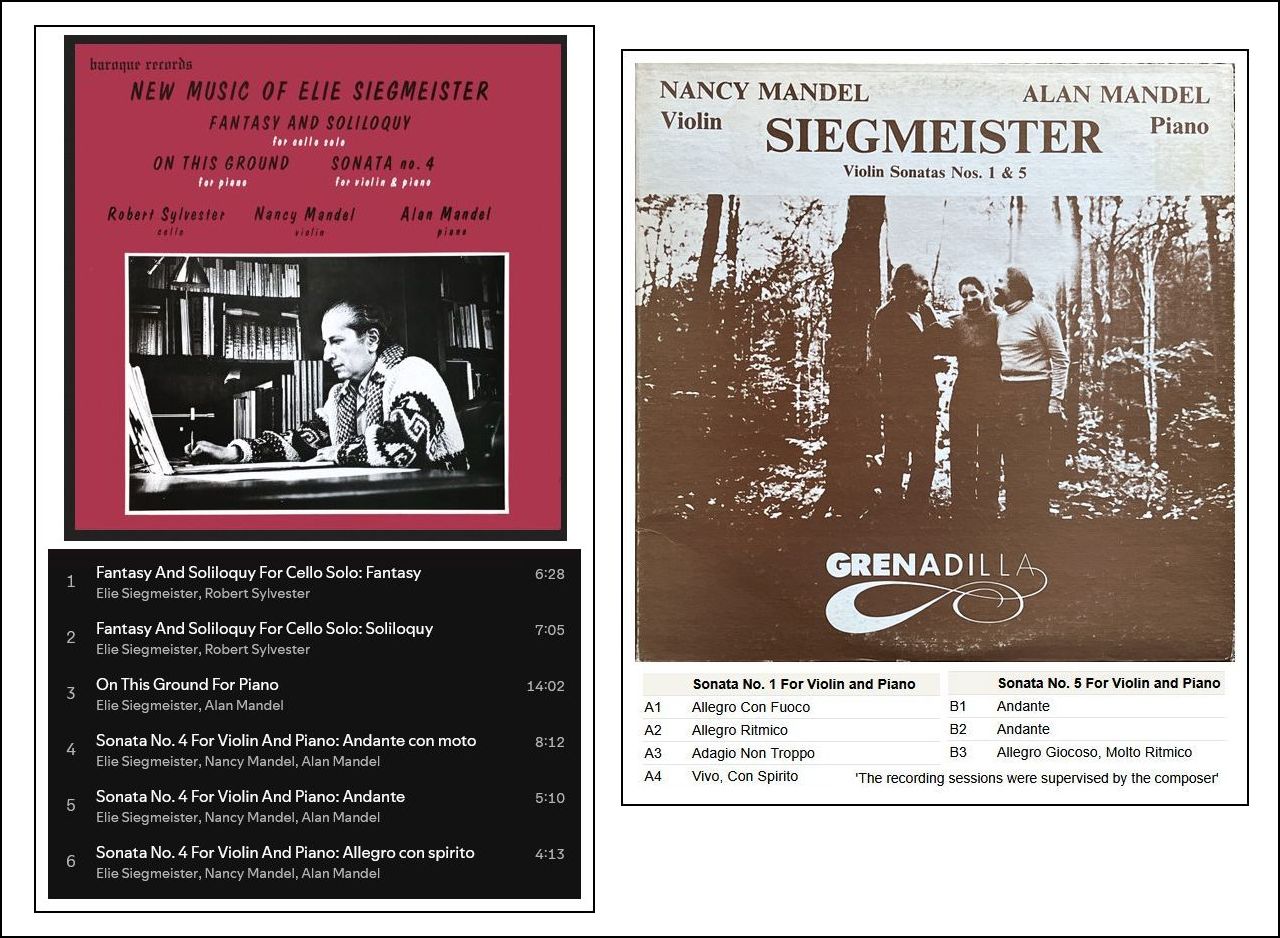

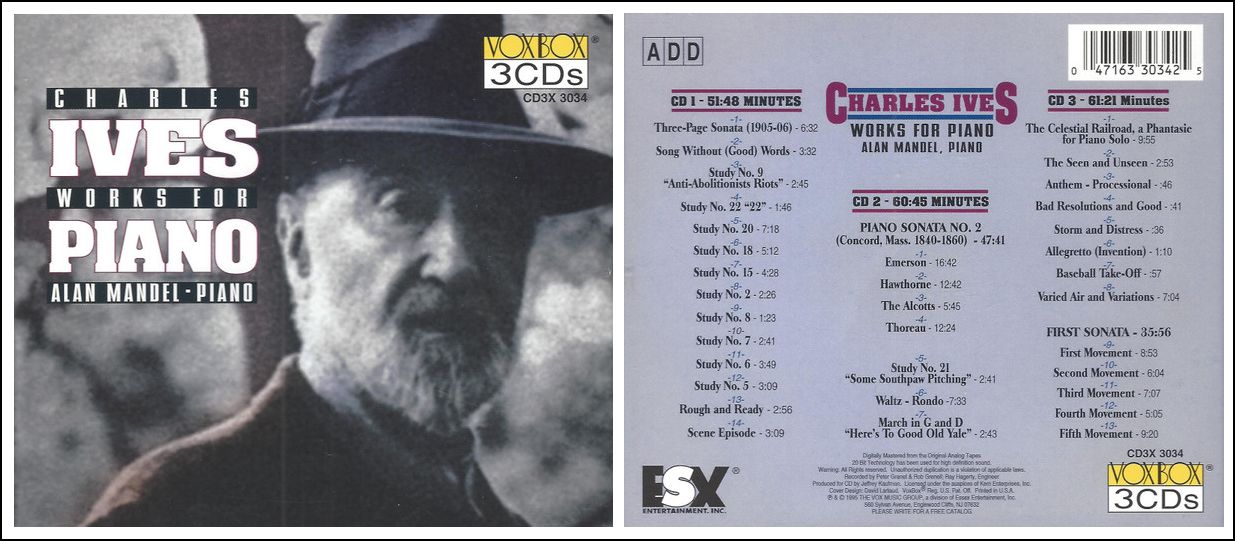

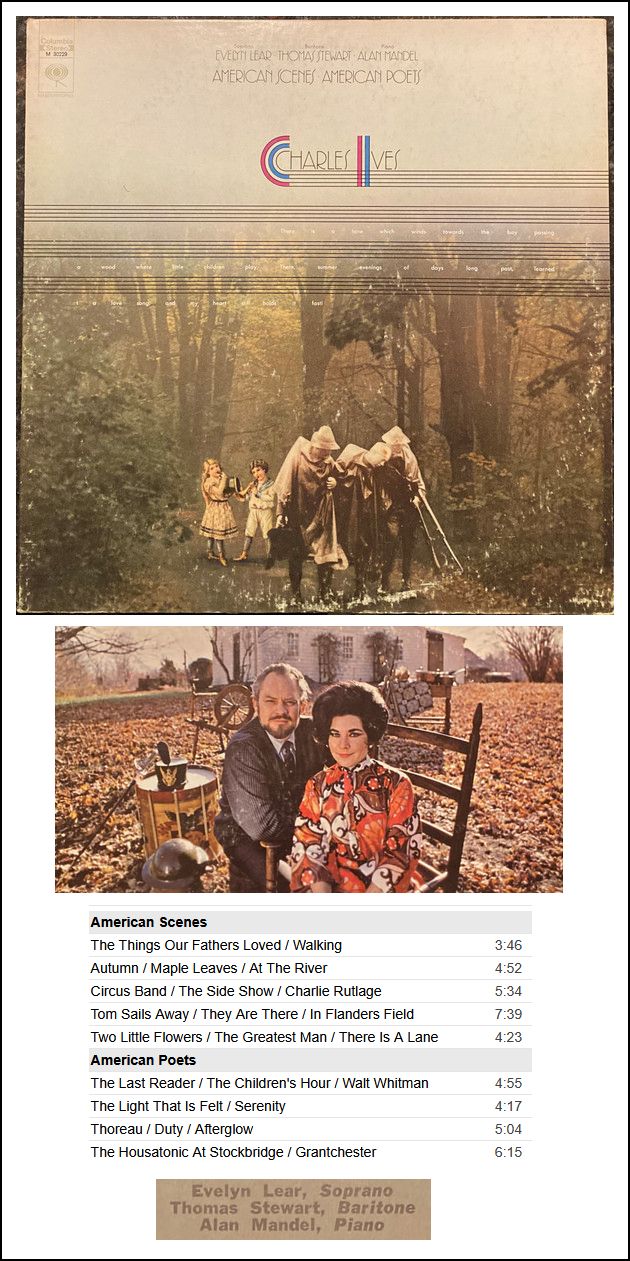

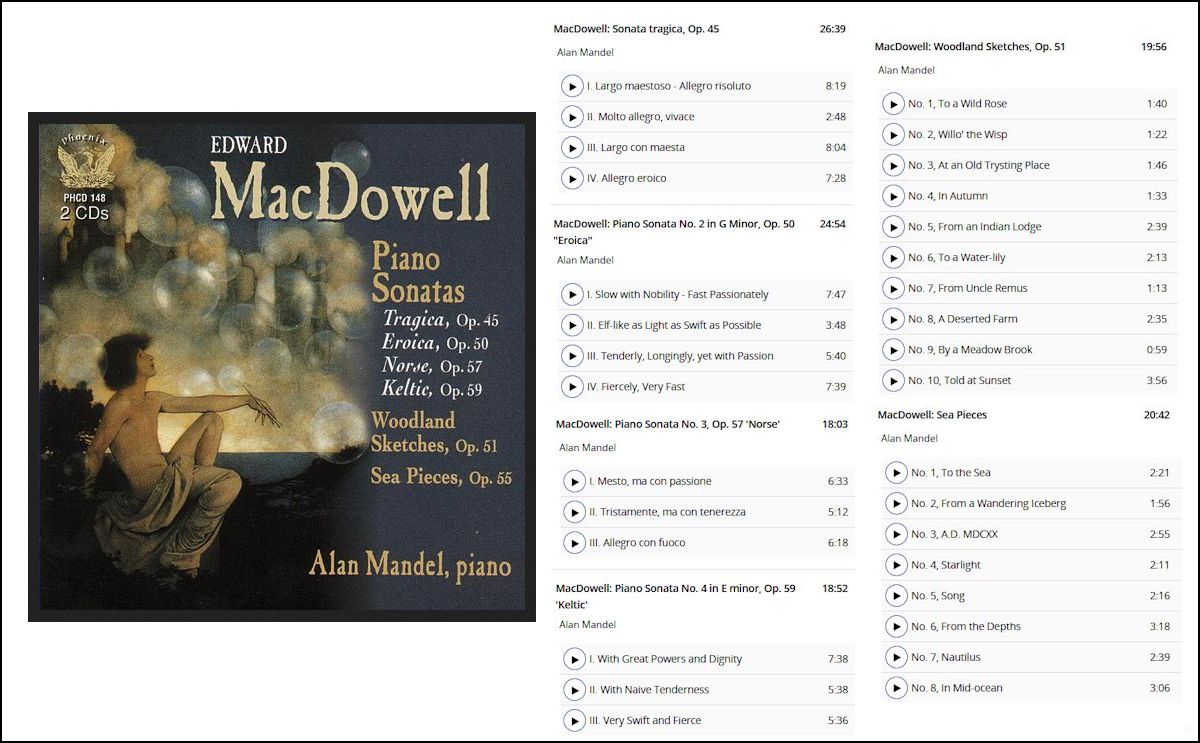

As a pianist, he made numerous tours all over the globe. One of Mandel’s

chief accomplishments was the recording of the complete piano works

of Charles Ives. [CD re-issue is shown below.] He composed a Piano

Concerto (1950), a Symphony (1961), as well as piano pieces, and songs.

|

In October of 1992, Alan Mandel was in Chicago, and graciously agreed

to meet me for a conversation. He was very good-natured, and along

with the deep understanding of the repertoire, there was much laughter during

our chat.

Needless to say, we spoke of many things, but he discussed the works

of Charles Ives at great length. As usual, names which are links on

this webpage refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.

Portions of the interview were aired on WNIB, Classical 97, and now [2025]

I am pleased to present the entire encounter.

Bruce Duffie: You’re a pianist, and a teacher, and

an artistic administrator. How do you balance those various sides

of your career?

Alan Mandel: It’s very difficult, but somehow

it all works out. It’s a matter of being organized, and not allowing

the administration to erase time to practice.

BD: In your head, you’re primarily a pianist?

Mandel: Yes, I’m a pianist more than anything

else, but I try to do as well as I possibly can as a teacher and as an

administrator.

BD: What kind of courses are you teaching?

Mandel: I’m the head of piano, in addition to

being the head of music at the American University in Washington, D.C.

I teach piano lessons, but I’ve also taught a lot of courses on

Ives, and Beethoven, and theory, and so on. I did graduate work

at the University of Pennsylvania with George Crumb and George Rochberg, and

I want to say after all the people you’ve told me you’ve interviewed,

it is an honor to be interviewed by you.

BD: It’s my pleasure. It’s nice to find

a performer that plays a lot of these composers that I have interviewed.

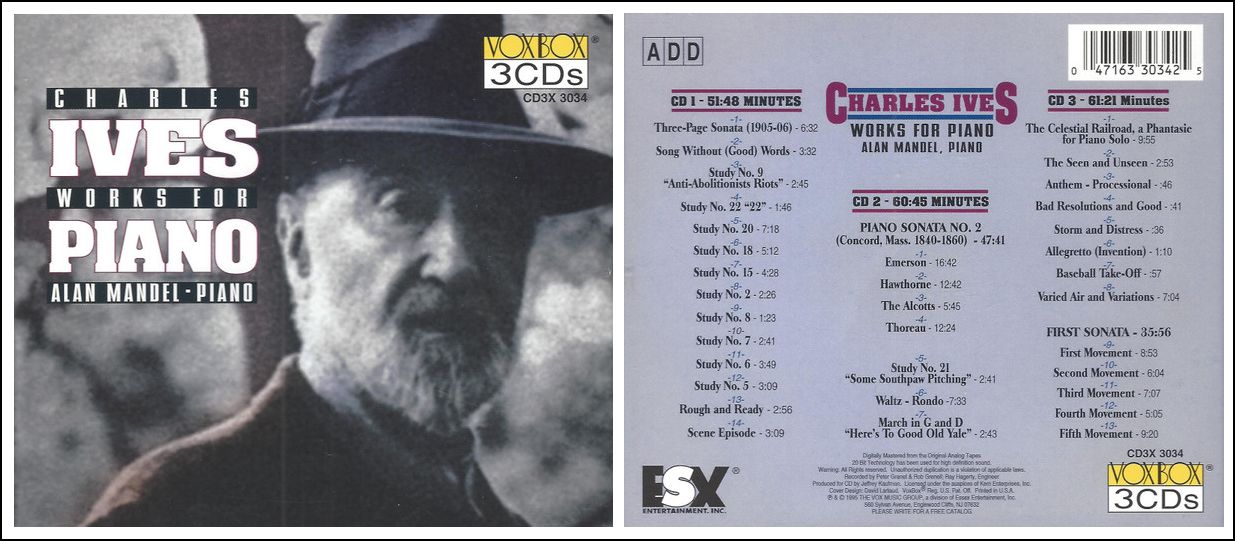

You’ve made somewhat of a specialty of seeking out modern living

composers to play their music. [Vis-à-vis the recording

of Ives songs shown at right, see my interviews with Evelyn Lear, and Thomas Stewart.]

Mandel: Yes. While it’s wonderful to play

the millionth performance of the Appassionata sonata of Beethoven,

it’s much more exciting to do unusual music, and to present it to audiences.

BD: Is it more significant to play the first performance

of a new work, or perhaps the fifth performance of an almost-new work?

Mandel: That’s immaterial. I enjoy giving

either the first performance or the fifth performance. Very often,

if I give the fifth performance, it might be in a different city, or in

some other year.

BD: A number of composers have mentioned that

getting first performances is not too hard, but it is that third and fourth

and fifth performance which are more difficult.

Mandel: Yes, I totally agree with you, but I feel

I can be of most service and give the biggest contribution if I play

music by living composers, and by unusual nineteenth-century composers.

BD: Do you always seek out the non-standard repertoire?

Mandel: Yes, of course. I live in Washington,

the city with the greatest possible library in the world. The Library

of Congress has, for example, a better French collection than the Bibliothèque

in Paris. Take my word for it!

BD: When you get a piece of music in your hand,

how do you decide if it is worth the time and effort to learn it, and play

it in public?

Mandel: That takes experience just like a conductor.

I have the ability of looking at music and being able to hear it.

BD: Then what are you looking for, or what are

you listening for in your mind’s ear that will touch you?

Mandel: That’s a very good question. I think

it was Artur Schnabel who said that preference is a very mysterious thing.

I might like something and somebody else might not. Again,

that comes with experience, and audiences will have to trust me. They

might like it, or they might not. It’s a matter of emotional appeal,

expressive appeal, and communication, perhaps in that order.

BD: Can I assume that if you do take the trouble

to learn it and work on it and present it, it has touched you?

Mandel: Very definitely, yes. That’s the

first order of business in my opinion.

BD: Are there some specific things that you look

for, or do you know immediately just reading through it once that it will

work or not work?

Mandel: I don’t know. Pieces I have performed

have had such a broad range of styles. I don’t know what turns me

on to a piece, but it’s that mysterious ‘je ne sais quoi’. [Both

laugh] I’ve performed a huge amount of American music. American

music used to be my specialty, and perhaps it still is, but as the director

of the Washington Music Ensemble, we’ve given quite a number of festivals

of music of different countries, such as France, Germany, Scandinavia,

and Canada, as well as three festivals of the music of the United States.

BD: Was the music all by living composers from

those countries?

Mandel: Almost all, yes. Sometimes it was

by dead composers, but they live through their music. Sometimes

we go back. Most of our festivals have included music by unusual

composers. Lately, we’ve been doing some standard repertoire because

we’ve got to keep our audience, although we have built a name for doing

unusual music.

* * *

* *

BD: With your experience of new music, you don’t

need to give specific examples, but are there pieces which either fairly

soon or in the future will take their places alongside other standard pieces?

Mandel: I don’t know. I hope so. It’s

too early to tell. I have found some great composers as a result

of my research both in the twentieth century and in the nineteenth century.

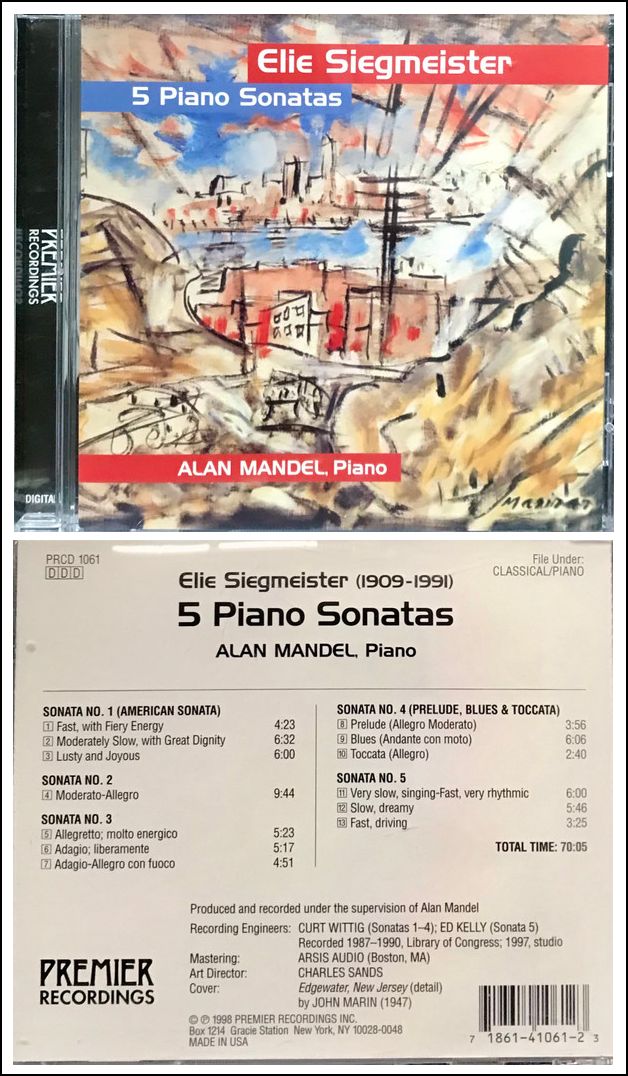

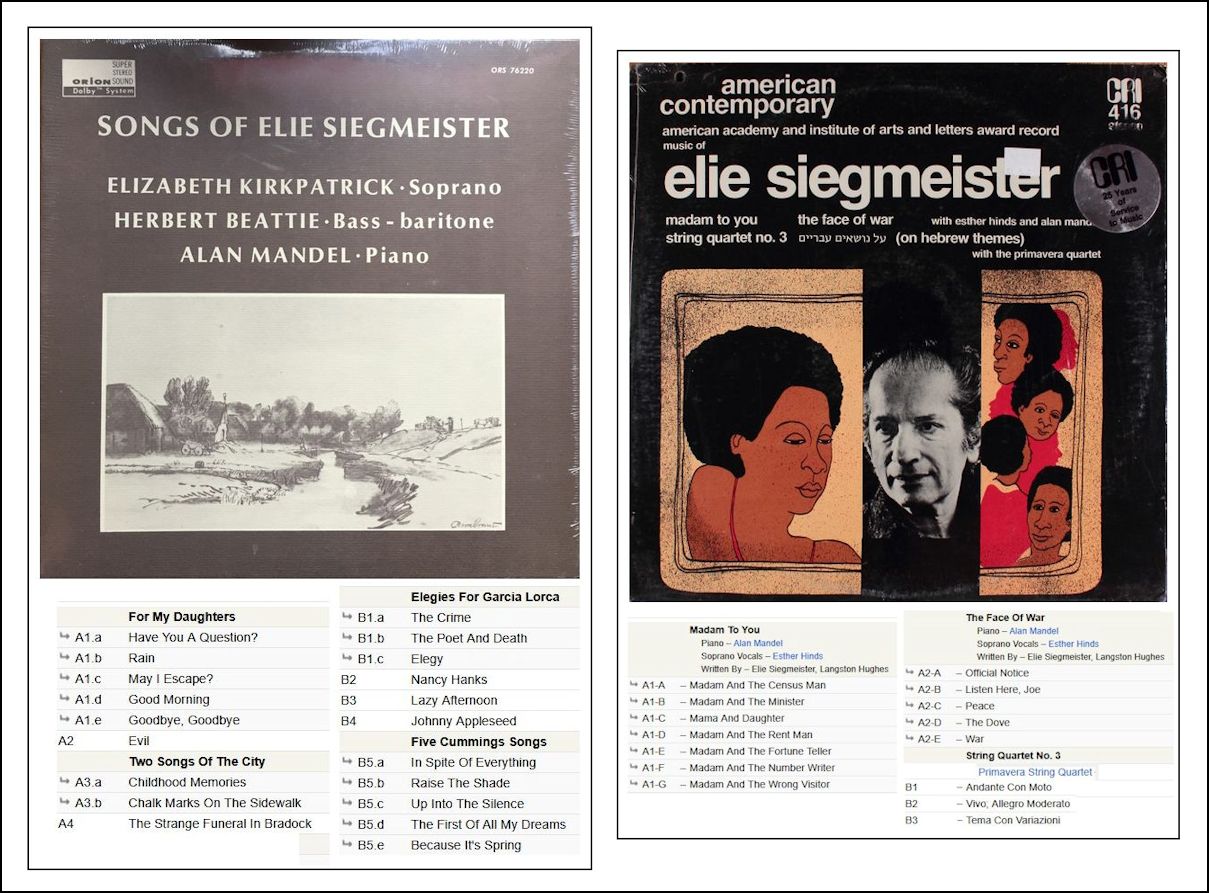

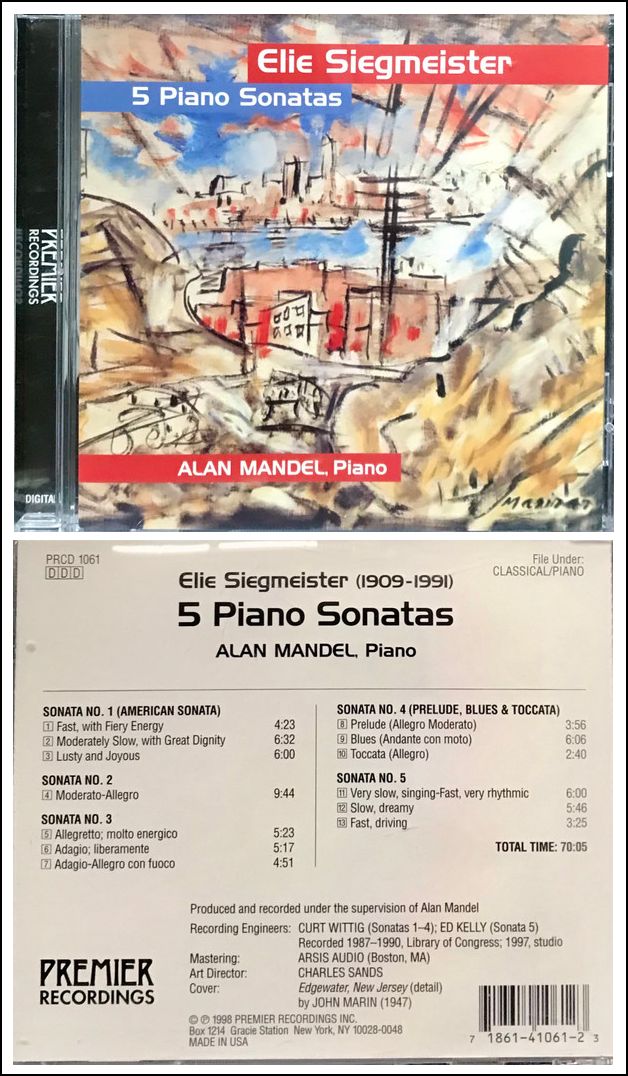

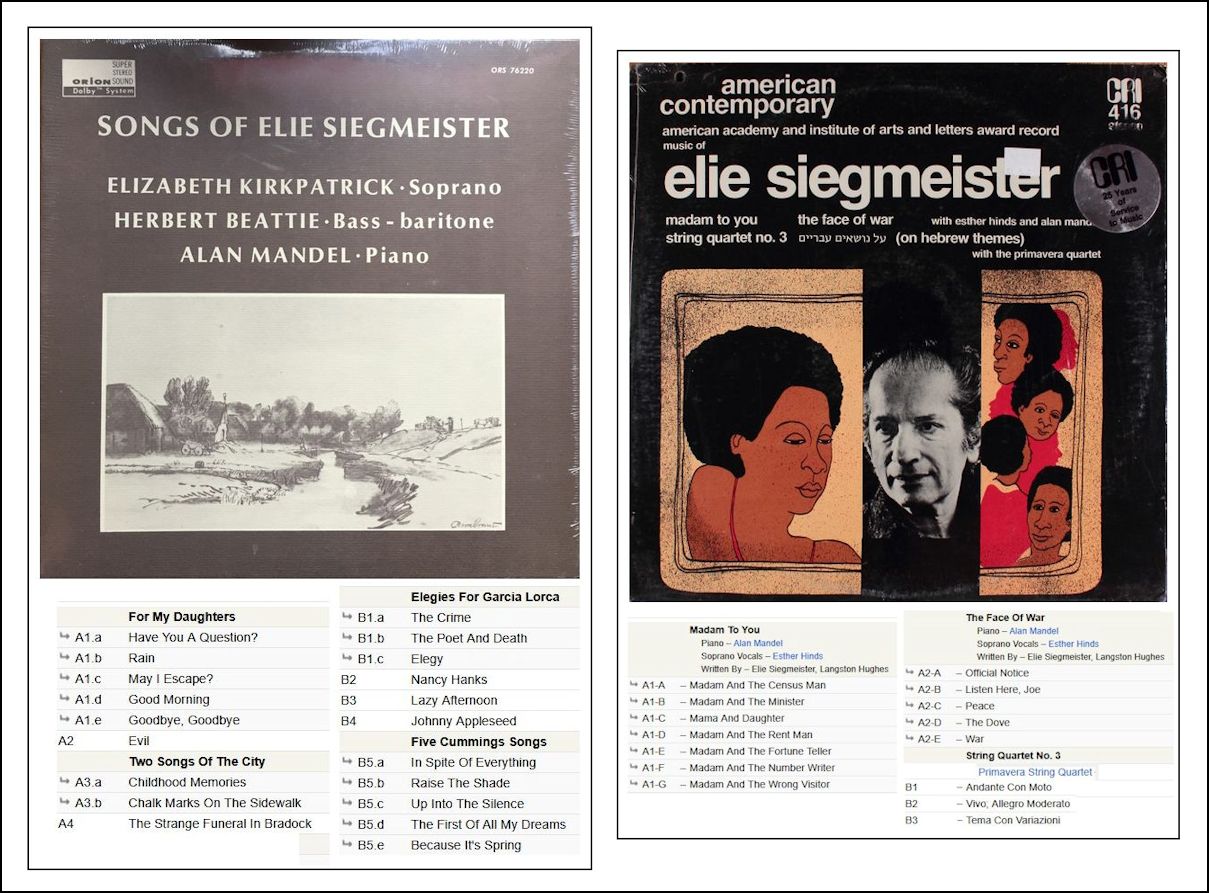

It all started with Charles Ives. My father-in-law, Elie Siegmeister first played

for me the Ives ‘Concord’ Sonata, and at that time I didn’t much

like it. But some months later I looked at it again, and I decided

I liked it. I scheduled it for concerts, and in New York the head

of a Desto Records happened to be in the audience, and he asked me to record

the complete works of Charles Ives. That’s how it all started.

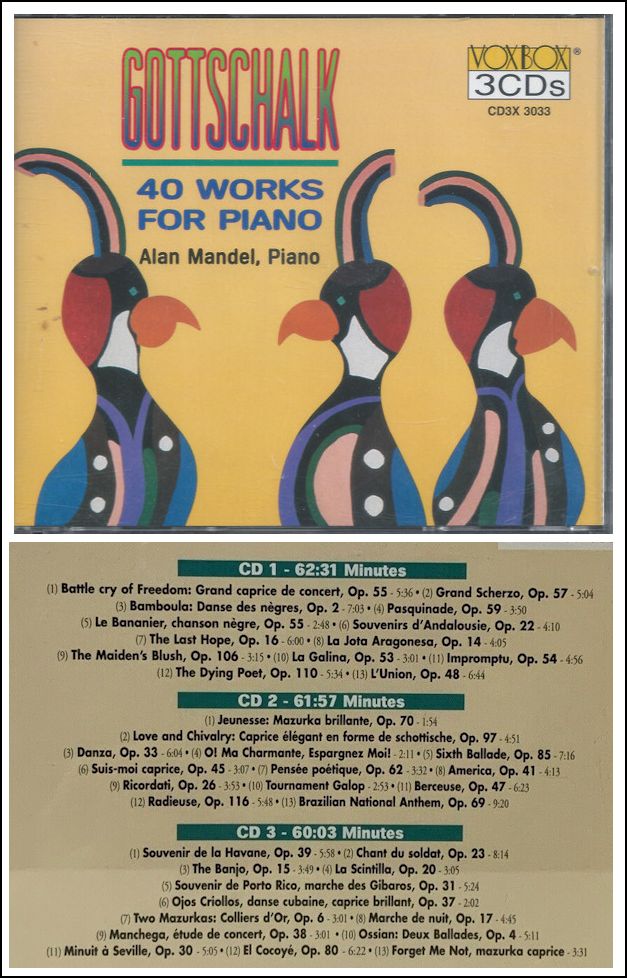

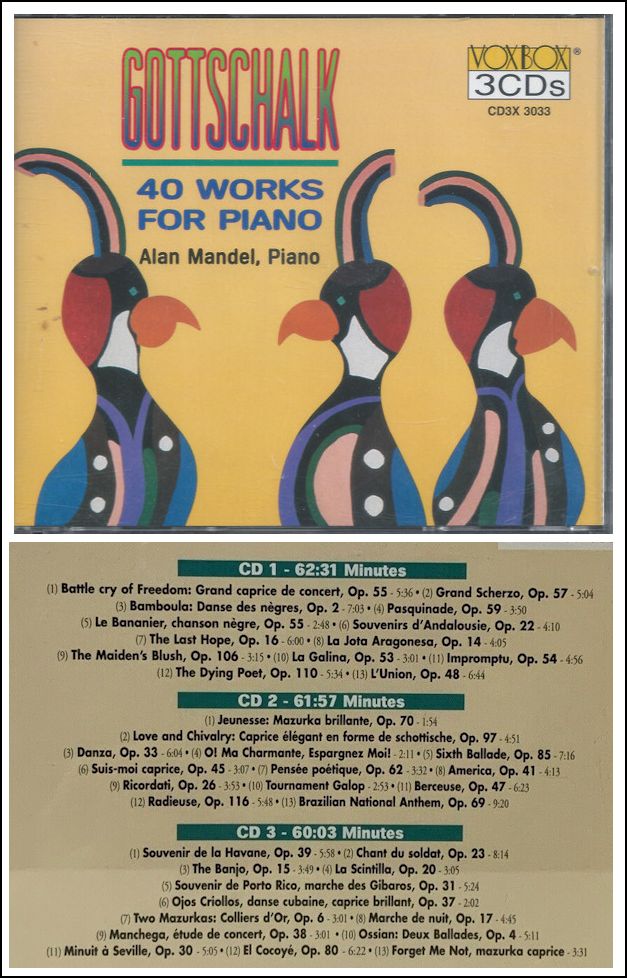

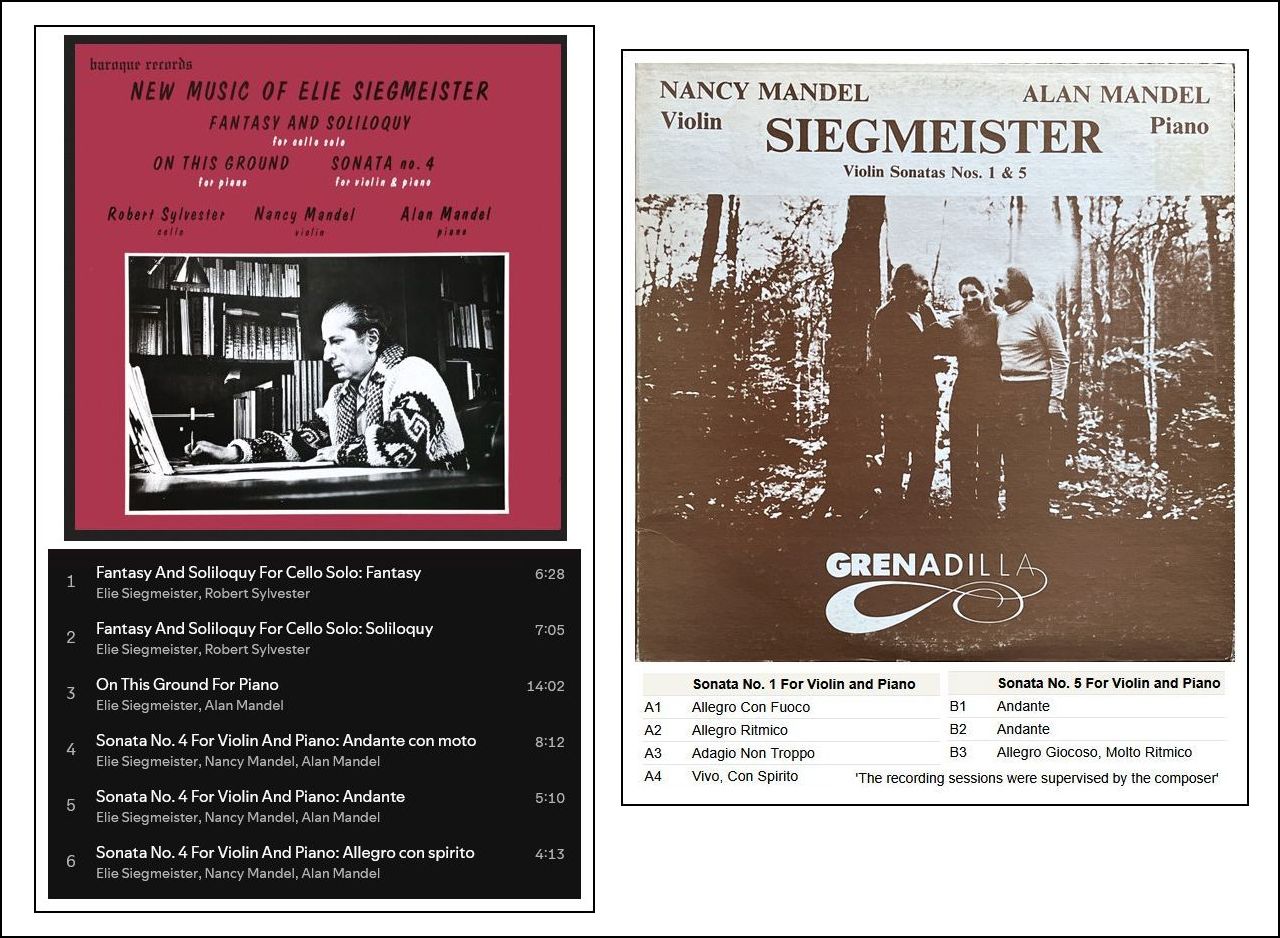

From there I did forty pieces by Louis Moreau Gottschalk, who, in my opinion,

was the first great American composer. [CD is shown at left.]

BD: He is sometimes called America’s First Super-star.

Mandel: That’s right.

BD: [Being quietly skeptical] If he was

such a great composer, and was a super-star, why has his music essentially

been forgotten today?

Mandel: He had a renaissance in 1969 with the 100th

year of his death, and some of his pieces are better forgotten. [Laughs]

But there are definitely some minor masterpieces by him.

BD: Minor masterpieces, and also some major masterpieces?

Mandel: I would say so. The Banjo,

which he wrote when he was sixteen years old, is extraordinary, and the

Souvenir de Porta Rico is also a masterpiece, as well as Bamboula,

and some of the other piano pieces. His most famous pieces were The

Last Hope and The Dying Poet, which were very well made pot-boilers.

When I was a little boy, my mother used to play for the silent movies. She’s

ninety-four years old now, and I remember as a little boy hearing her

playing those Gottschalk pieces, as well as rags.

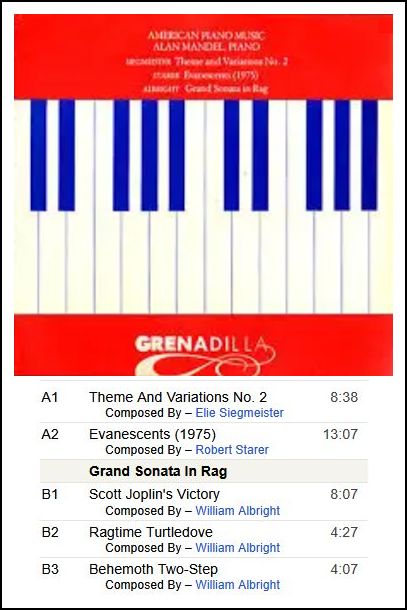

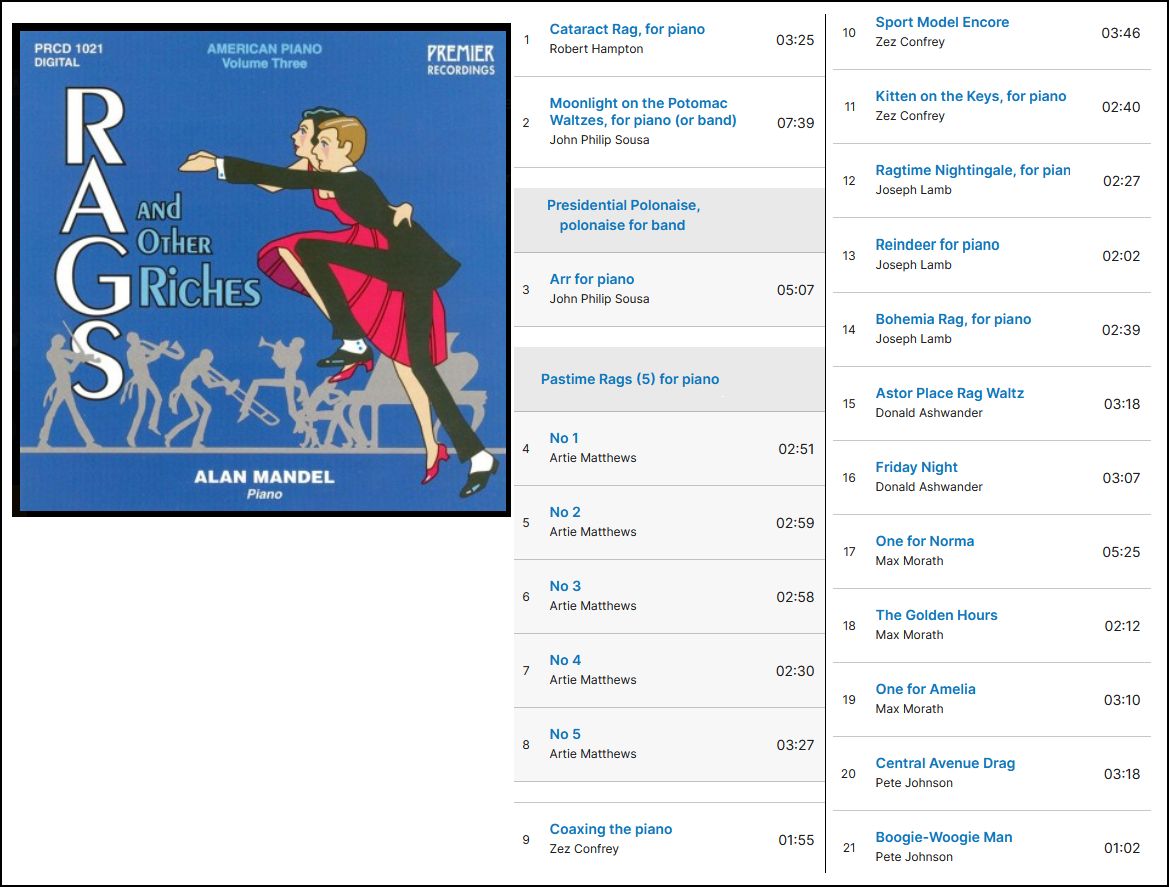

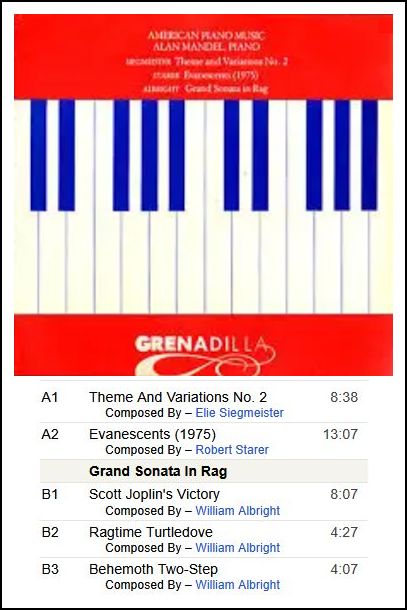

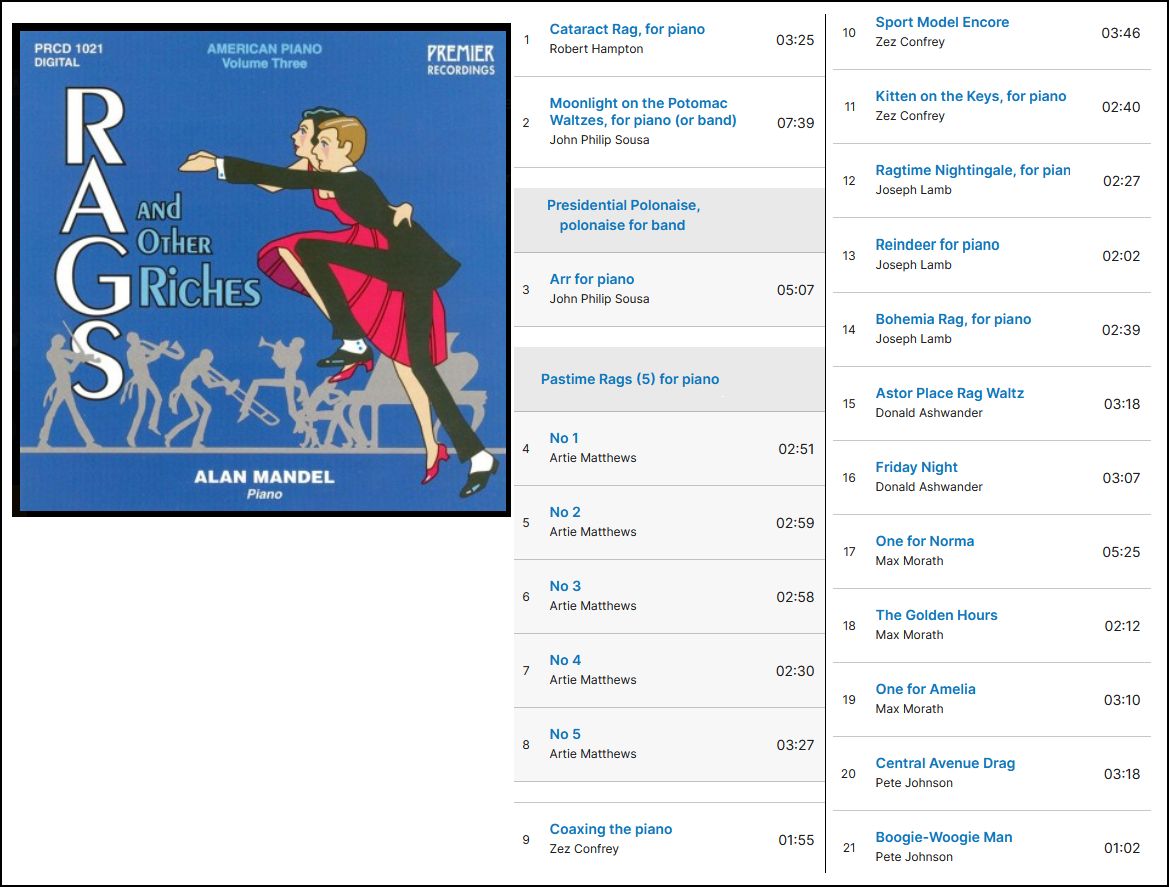

BD: Your newest record is of Rags by various composers.

[CD is shown at the bottom of this webpage.]

Mandel: Yes, that’s right. I think I was

the first pianist to combine in concert serious music and ragtime.

BD: Do they really go together?

Mandel: It works with American music. It

doesn’t work with late Beethoven, certainly, but with Siegmeister, or

Ives, or other such composers, it works beautifully.

* * *

* *

BD: You’ve worked with a number of composers who

are still living. When you’re working on their music, do you help

them as much as they help you?

Mandel: Sometimes I would say so. Sometimes

composers need to hear their music, and they might make changes.

It’s very interesting to work with living composers. Some of them

have a very, very clear idea of what they want, such as Elie Siegmeister,

for example. He knew exactly what he wanted, and George Rochberg

in a different way, knew exactly what he wanted. With some other

composers, such as George Crumb, or Robert Starer, it is like

pulling teeth to get them to criticize and make suggestions.

BD: Does working with living composers give you

additional insight to those who are no longer alive?

Mandel: I think so. Partly from experience,

and partly from my own interpretation, I try to ascertain to the greatest

possible degree, as much as possible what the composer would have wanted.

BD: Is there only one way of playing any piece

of music?

Mandel: No. It might be different on Monday

or Tuesday, but I have a very clear idea of what I want to do, otherwise

I wouldn’t do it. Some pieces I’ve been playing for many, many years.

With the ‘Concord’ Sonata, I must have given over a thousand performances

of that.

BD: [Somewhat surprised] Really???

Mandel: Yes, and every time I go back to it,

I learn something new in it, and something changes.

BD: Does your interpretation always grow?

Mandel: It always grows. That’s what I

think makes a great piece, because it can never be complete.

BD: Are there some pieces that you can get to

the bottom of right away, and then there’s nothing more?

Mandel: Yes, sure, and after one or two performances

it becomes a little boring, and I go to something else.

BD: [Playing Devil’s

Advocate] It becomes boring for you, would it necessarily become

boring for an audience that’s not heard it before?

Mandel: If it becomes boring to me, then inevitably

it will eventually become boring to an audience. But I wouldn’t

find it satisfying to play it any longer.

BD: You have to have the sparkle in order to convince

an audience?

Mandel: Yes, sure. I have to have the sparkle,

and the emotional charge, and the challenge. Then, hopefully, the

audience will respond.

BD: Again, without necessarily naming names, are

there some pieces that you looked at twenty years ago and felt they had

nothing, and then you come back to them and found there was something

really interesting?

Mandel: Yes, I would say so. The first time

I heard the ‘Concord’ Sonata I didn’t like it, and then the second

time, some months later, I loved it. For many years, I didn’t

like Elie Siegmeister’s First Piano Sonata, the ‘American’ Sonata,

although I played it a few times. Then lately I played it in a few

different places, including Washington, and I decided I really like it.

[CD of all 5 piano sonatas is shown at right.]

BD: Is it not unreasonable to expect a reaction

to it by the audience when they only get to hear it once in a concert?

Mandel: [Thinks a moment] I hope that I

communicate with them, and I hope they like it. It’s my fervent

hope that they like it!

* * *

* *

BD: As a performing pianist, how conscious are

you of the audience that is sitting out there to your right?

Mandel: I try to think of them as a living entity,

and I try to communicate with them. However, at the same time I’m

concentrating as fully as possible on the music. I’m at the service

of the music, and the audience is the service of the music.

BD: When you’re concentrating on the music, is

that technically or emotionally?

Mandel: Emotionally. The technique is just

the means to the end. Hopefully the technique is all there.

BD: Once you’ve got all of the technical problems

solved, that’s when you really begin to learn the piece?

Mandel: I begin to learn the piece right away

as a concert performance. If I do that, then it’s much more interesting.

Believe it or not, then the technique is much better.

BD: Do you play differently in a small hall with

a couple of hundred people, and a large hall of two or three thousand?

Mandel: I enjoy playing more for two or three

hundred people, but if I play for two thousand people, that’s fine, too.

Even if there’s just one person, I enjoy it. I have a wonderful time

giving concerts. I’m very lucky in life to be able to give concerts.

Some people hate their jobs, but that doesn’t include me!

BD: About how many concerts do you give each year?

Mandel: Around fifty. That’s about as much

as I can handle, because I also have teaching responsibilities towards my

students, which I take very seriously.

BD: Are you impressed with the talent that you

hear coming out of the fingers of your students?

Mandel: Yes, I would say in Washington, sure.

I have a couple of very fine students every year, and some others that

are quite good.

BD: I assume you encourage all of your students

to work on new music as well as old music.

Mandel: As much as possible, however I also enjoy

very much giving classes. It’s a different kind of experience, and

giving a class is just like a performance.

BD: You prepare for it, and rehearse, and then

deliver it?

Mandel: Yes, but I don’t read from notes.

I have main works from which I discuss different ideas.

BD: You have notes but no script?

Mandel: That’s right.

BD: That’s the same way I do it when I’m giving

a lecture. I’ll make some notes, and then refer to them just to

make sure that I’m talking about the next sequential topic. But I

don’t have a written script.

Mandel: That’s right. But I’ve also been

very lucky to be able to do a lot of traveling in connection with giving

concerts. I’ve enjoyed very much being in fifty different countries.

BD: When you go to other countries, do you take

a lot of American music with you?

Mandel: Sure. That’s what I’m known for,

so that’s what I do, and that’s what I’m asked for. I’ve played in

very sophisticated countries, and very unsophisticated countries.

BD: Do you tailor your program at the sophistication

level for the audience, or for the country?

Mandel: To a slight extent, but mostly I

play whatever I’m very interested in at the moment.

BD: Okay, then what are you interested in this

moment?

Mandel: At this moment I’ve been playing

a lot of music by Ives, Gottschalk, Siegmeister, and Irwin Bazelon. I did

something last year which was very unusual, and which I’ve always wanted to

do, which is the last three sonatas by Beethoven, along with the ‘Tempest’.

BD: Eventually will you wind up with all thirty-two

in your fingers?

Mandel: At one time or another, I have played

almost all of them. You never know... it will be however the spirit

strikes!

BD: Is it particularly refreshing to come to a

known Beethoven masterpiece after playing all kinds of American music,

and being away from the Beethoven style for a long time?

Mandel: The process is very much the same.

I just study the music, and do whatever I think is right. However,

the style might be completely different. I grew up in New York City,

in the Bronx, and so it’s part of me. There’s no getting away from

it. On the other hand, I’ve studied Beethoven since I was four or

five years old, and so that’s also very much part of me.

BD: I read that you started taking piano lessons

at aged three and a half.

Mandel: That’s right. My mother took me

to The Wizard of Oz, and I came back and played music on the piano.

So she took me right away to some teacher that had been recommended.

BD: Is three and a half too young to really start?

Mandel: It all depends. No, not necessarily.

My brother who is seven years older than I, had to be forced to

practice. I laughed when he made a mistake, and he didn’t like that!

[Both laugh]

BD: But you just had to be dragged away from the

piano?

Mandel: Pretty much, yes. I had piano teachers

who were really fascist. You can’t imagine, but it all worked out

well in the end.

* * *

* *

BD: You travel all over the country and all over

the world, and in each place you are presented with a different piano.

How long does it take you before that instrument is yours?

Mandel: A couple of chords. You just find

your voice, and you do it. I’ve played on wonderful instruments.

At Cornell University [in Ithaca, New York], they had a wonderful Bösendorfer

that Badura-Skoda

had given them. It has two different actions. One of them

was very brilliant for contemporary music, and the other was soft and

velvety for Schubert and Mozart. It happened that the first half

of my concert was Schubert and Mozart, and the second half was contemporary.

So then I asked them to change the action, which they did.

BD: [Surprised] They came on stage and pulled

out the old action and put in the new one???

Mandel: [Smiles] Yes. So that was

heaven. On the other hand, when I played in Lebanon, the piano

tuner tuned the lower half of the piano, and forgot to tune the upper

half. I played George Crumb on that, and whenever I made a histrionic

gesture, the audience applauded. So that was fun too, even though

the piano left something to be desired.

BD: Your left hand was okay, but the right hand

was not?

Mandel: That’s right. You do the best you

can, that’s all. Some years ago I told my mother about something

bad that had happened to one of my friends. At her age, she can

be philosophical, and she said that even if it’s snowing today, one of

these days the sun will come out!

BD: Just like Annie!

Mandel: That’s right. [Both laugh]

BD: Having been a pianist herself, is she particularly

pleased that you have become a performer on the instrument?

Mandel: Yes. She’s proud of me, and I’m

proud of her.

BD: Would she have been equally proud if you’d

been a violinist or an oboe player?

Mandel: I think so... after all I’m her son!

BD: You mentioned that the Lebanese audience

would react when you made a gesture. How are audiences different

from town to town, and country to country?

Mandel: Sometimes they’re more or less demonstrative.

Scandinavian audiences are a little bit less demonstrative, but underneath

it all they’re very warm. Although it doesn’t appear that way, they

really are. Some audiences go wild, and being a performer, I enjoy

that. I just think of them as an enthusiastic positive mass of

people. I try to play for a particular person in the audience who

seems to be sympathetic, but that’s a personal thing.

BD: What advice do you have for audiences that

come to hear one of your recitals?

Mandel: Please don’t cough! [Both laugh]

Try to be positive, and try to be open. I don’t seem to have

any problems with audiences. I enjoy them. I have a ball when

I give concerts.

BD: How do you design your programs? Do

you try to include some old music and some new music?

Mandel: Sometimes chronologically, sometimes according

to idea. I’ve tried out all kinds of different ideas.

BD: Some work and some don’t?

Mandel: That’s right.

BD: Of the ones that don’t, might they work in

other places?

Mandel: They might, but if they don’t work, I

usually don’t try them again. Sometimes I’ve given concerts that

are decidedly non-chronological. If something is a real blockbuster,

or it’s very profound, it could work very well as a last piece no matter

when it comes from. Sometimes I like to put contemporary music

in the middle, so that the audience has to stay for it.

BD: Put it last before the intermission?

Mandel: Yes, or right after the intermission,

so they’re refreshed. It all depends. But the main thing is

that I have a wonderful time giving concerts.

BD: Do you also play chamber music and orchestral

concerts?

Mandel: Oh, very much so. As my career has

worked out, I haven’t given as many orchestral concerts as solo concerts

and chamber concerts. Being Director of the Washington Music Ensemble,

that has been a wonderful experience. [Pauses a moment] Let

me say a few things about Chicago. You have a wonderful city.

I had a terrific time going to the Art Institute. It has a terrific

American collection, as well as a wonderful French Impressionist collection,

and a few others. I enjoyed the Art of the Ancient Americas very

much.

BD: This is all very visual, and yet your music

is purely aural. Do you try to get some kind of visual into the

aural presentation of your music?

Mandel: Sometimes, but the audience can take what

they like from it. That’s something which is silent and personal,

and has nothing to do with what comes out. At home I do have an art

collection, so in addition to a piano they’re both sides of me. I

feel that there’s some union there.

* * *

* *

BD: In the music that you play, where is the balance

between the artistic achievement and an entertainment value?

Mandel: I don’t know the answer to that. That’s

for you to figure out. I just do something that’s uncomplicated

and simple. I find the music, and by some mysterious process I like

it, and I work on it as hard as I possibly can. Then I perform it,

and I hope it’s both expressive, and communicative according to the highest

values of Western civilization, as well as being entertaining.

BD: So you want it all!

Mandel: Yes, sure! I want to have fun, and

I’ve been told that I’m a very athletic and visually

interesting pianist when I perform. So I hope it’s entertaining.

BD: [Gently protesting] But I thought

that the entertainment should come from the spirit of the music, not the

gestures.

Mandel: Yes, that’s right. The gestures

are totally unconscious. Different people have different styles.

When Arthur Rubinstein played the Ritual Fire Dance [Falla], his

hands went up and down very high. He said he could play it with

his hands going not so high, but audiences wouldn’t like it that much.

So that was conscious. I’ve tried to play consciously in a very

demonstrative way, but somehow it doesn’t work as well... at least I

don’t think it does. It could be just my feeling...

BD: It would be interesting to play exactly the

same concert two nights in a row, one very quietly and the other very flamboyantly,

and see what kind of reaction you get.

Mandel: Of course, when I play an Adagio

from a late Beethoven sonata, I don’t go all over the place.

BD: Let me ask a big philosophical question. What’s

the purpose of music?

Mandel: The purpose of music to touch people,

to communicate the highest possible poetry and drama, as well as excruciating

pain and passion, and to express the highest possible values of Western

civilization.

BD: Always the highest?

Mandel: No, sometimes the lowest. There

is a broad range of emotion.

BD: Once you’ve got the highest and you’ve got

the lowest, what about everything in between? Do you want all of that,

too?

Mandel: Everything, yes. It’s a universe

out there.

BD: Can you bring all of this in one concert,

or is this over a series of concerts?

Mandel: I try to bring it every time. If I

play the ‘Concord’ Sonata or the ‘Hammerklavier’, that’s

a very wide range of emotion. Of course, if I play Webern, then it’s

a very narrow, but perfect range of emotion.

BD: I would think the ‘Hammerklavier’ on one half

and the ‘Concord’ on the other would be a gut-wrenching program.

Mandel: Oh yes, and I’ve done that. I know

that Rudolf Serkin played the Diabelli Variations on a concert, and

then, after the concert was over, he didn’t recognize his own wife! [Both

laugh] I try to give everything I possibly can in a concert, because

otherwise it’s not worth doing.

BD: So that’s the measure of success. If

you recognize people, you haven’t quite made it.

Mandel: That’s right... What did you

say your name was? [Both have a huge laugh]

* * *

* *

BD: What advice do you have for composers who want

to write for the piano?

Mandel: To just write music that’s true to themselves,

and to write with the greatest possible emotion. That’s the most

important advice I can possibly give. But I would be extremely loath

to give advice to composers. Composers have to do what they have

to do. There are so many composers. When you get known for

playing contemporary music, you get millions of scores in the mail or in

person. Hardly a week goes by when I don’t get a packet from Scandinavia.

I’ll have to get a new house...

BD: When you get all of these unsolicited scores,

are there some that you decide yes, you will play?

Mandel: Yes! I’m fantastically committed

for the next couple of years, but there has existed an occasion when I get

a score that I thought that I had to play, and then I played it right away.

I’ve been very lucky to be able to play all of this music that nobody

else has played.

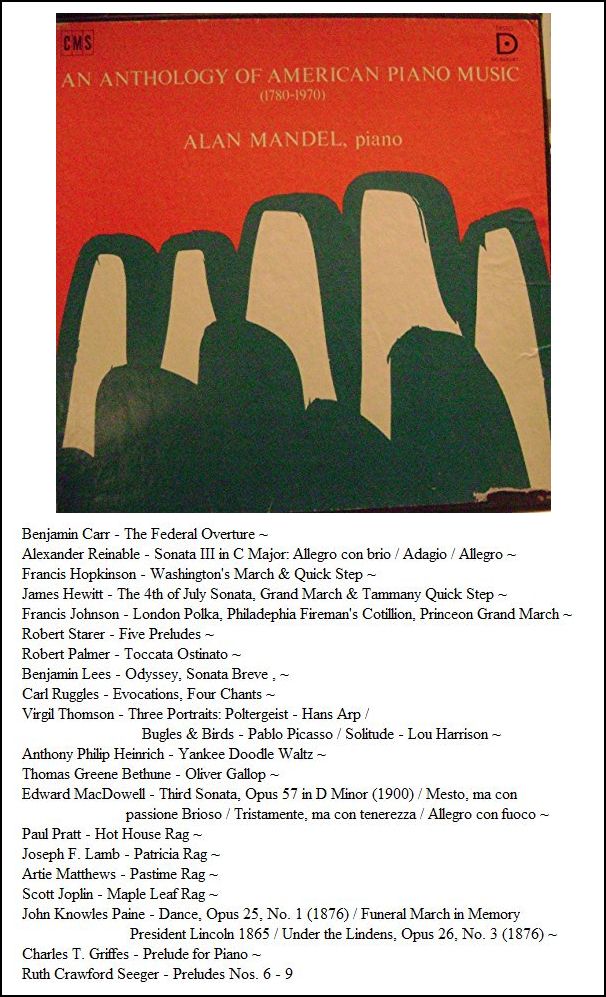

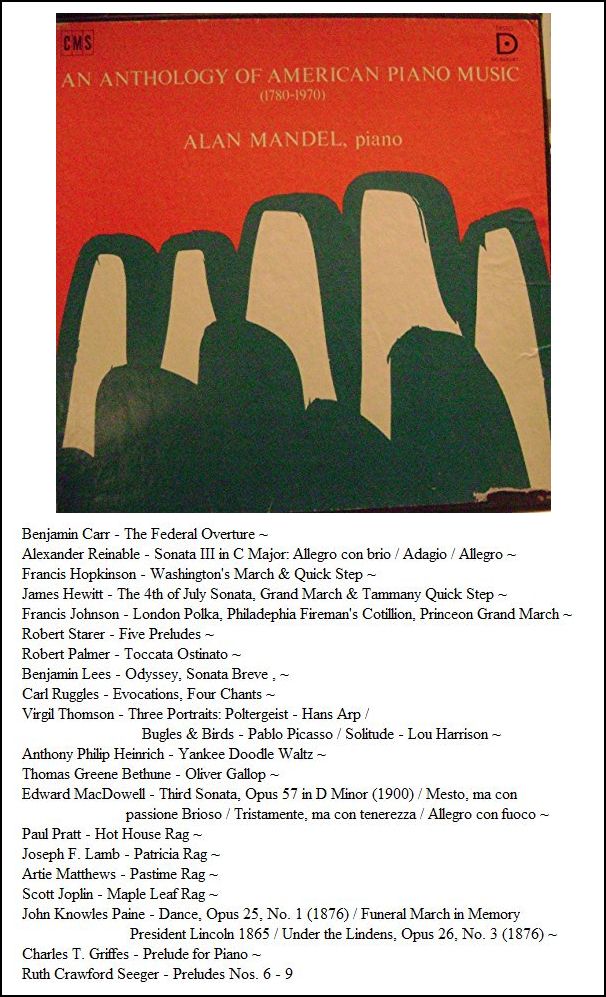

BD: You play a lot of music from America. Is

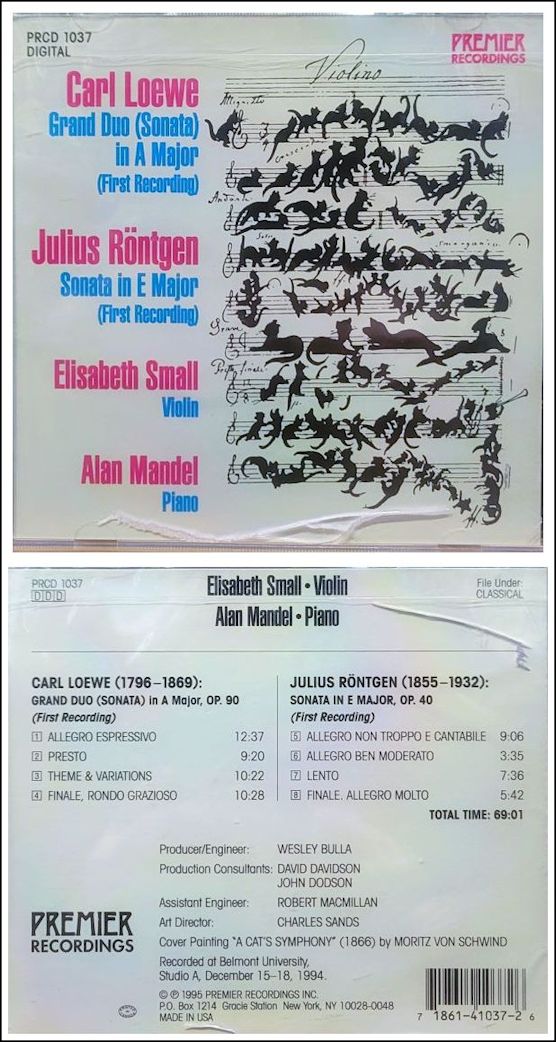

there an American sound, or is music, is music, is music? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Robert Palmer, Benjamin Lees, Virgil Thomson, and Lou Harrison.]

Mandel: Certainly there is an American sound.

However, with the explosion of communication in the world today,

the American sound is universal. I have found the American sound

in certain European composers. In La Création du Monde

by Milhaud, there are very definitely American elements.

BD: Even though the Milhaud is really a French

piece, and has a very French sound?

Mandel: Yes, that’s right. Nevertheless,

he used jazz elements one year before the Rhapsody in Blue. But

I find the American sound very attractive partly because I’m from New

York.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

Mandel: Sure! As long as there’s hope in

the world, and as long as the human spirit endures, there’s going to be

music.

BD: Are you at the point in your career now that

you expected to be, or that you should be?

Mandel: Who knows? I’m doing the best I

can.

BD: You don’t have a pre-set program of where

you should be by now, and that you should be playing in certain places

at certain times?

Mandel: I have a five-year plan. However,

that’s purely in my mind, and I do the best I possibly can in life.

* * *

* *

BD: Are you pleased with the recordings that you

have made?

Mandel: Yes! It’s

quite a different thing to make recordings than to give a concert.

BD: Do you play differently?

Mandel: Yes, sure. It is known that Vladimir

Horwitz did a Chopin Nocturne seventy-six times before he was happy

with it. I usually get it on the third time, or sometimes the fourth

time. But in any case, when you give a concert, you do the best

you possibly can. Inevitably there are mistakes, but the mistakes

evaporate into thin air. They don’t exist anymore. But with

a recording they’re permanent. I was talking to somebody from the

Foreign Service in Washington, who said that he heard some of my recordings

in India years ago. A recording is permanent, and it exists forever,

so it had better be right. That’s why you don’t hear any mistakes

in recordings.

BD: Are recordings too perfect?

Mandel: [Thinks a moment] I don’t have any

problem with not making any mistakes. Of course, as you know, for

recordings you can do sections. Some performers do separate notes,

and I don’t approve of that. I do sections. If I do a piece and

one section of it is not acceptable, then I do that section over again and

they splice it in.

BD: Is that not a fraud?

Mandel: No! I don’t think so. First of

all, I have to approve of it before it goes out. Therefore, if you

do a section, then that’s a musical entity. Perhaps it’s a fraud

if you just do one note at a time. That’s an illusion. But

on the other hand, if it does make a musical whole all together, then I

guess that’s all right. But I don’t do that.

BD: If you’re playing a piece in a concert

that you’ve recorded, do you feel that you’re competing against that record?

Mandel: No. Sometimes it’s totally different.

For example, I did the Ives way back then, and subsequently played

it many, many times. Sometimes it is totally different than on the

recording. There are many ways of looking at music, just as there

are many ways of looking at life.

BD: Would you then want to re-record the

Ives now with your more recent thoughts?

Mandel: One of these days I certainly will, but

there are so many other things for me to do.

BD: When you record the Ives for a second time,

people will start to compare. On the first he did this, and on the

second he did this. How do you reconcile the two? Is it just

the elapse of time?

Mandel: One is one way of looking at it, and the

other is another way of looking at it. There are so many ways of doing

Hamlet, or the Beethoven Fifth, or the Ives ‘Concord’ Sonata.

BD: They’re all right?

Mandel: I think so. They’re all right if, indeed,

they’re right. I have no apologies for making a recording of

the Ives in 1965, but now [1992] there are certain things I’d do differently.

There’s an interesting story about William Masselos, who recorded

the First Sonata of Ives. He recorded it many years ago,

and when I was going to make my recording, I had dinner with Bill about

a week beforehand. He said to wait and not record it. There

was another version Ives put down on paper just before he died, with many

different changes in it. He said that John Kirkpatrick gave it to

him a few days before he made the recording, and he made, in my opinion,

a very valid decision to go ahead and record it the way he learned it.

Bill showed it to me and gave me a Xerox of his copy of it. It

had many interesting changes. For example, one quote of ‘What a

friend we have in Jesus’, which is in the slow movement of the First

Sonata, is changed so that it is exactly the same as the original hymn,

and I used that. There’s also one place where he has special chords

that sound like bells, and I overdubbed that into the recording. It’s

absolutely impossible to do otherwise.

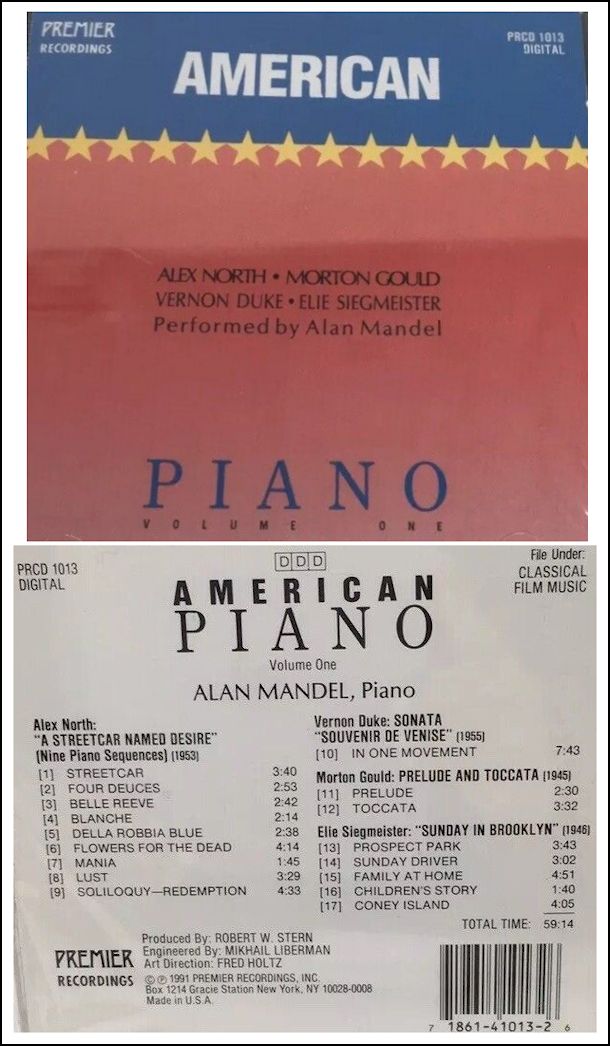

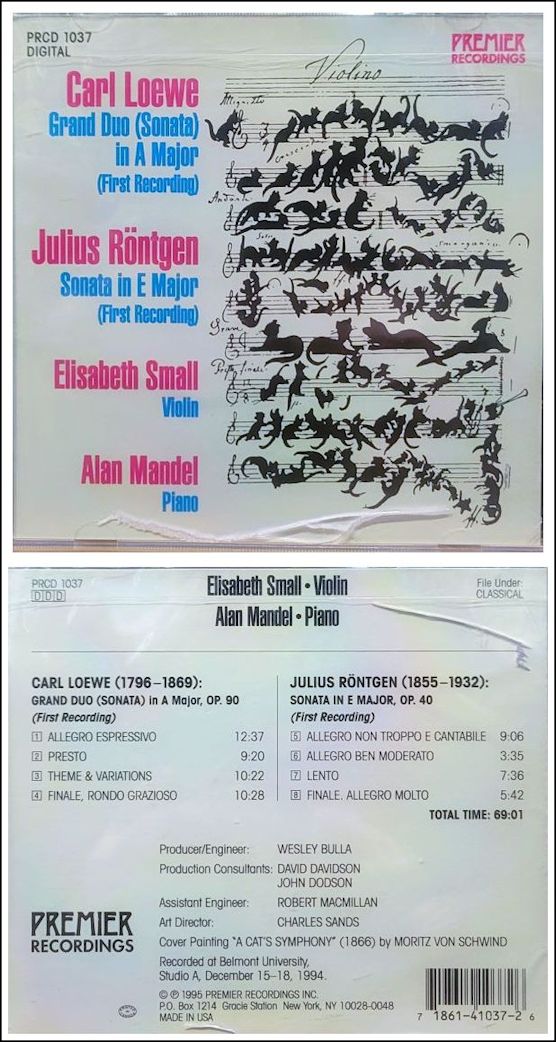

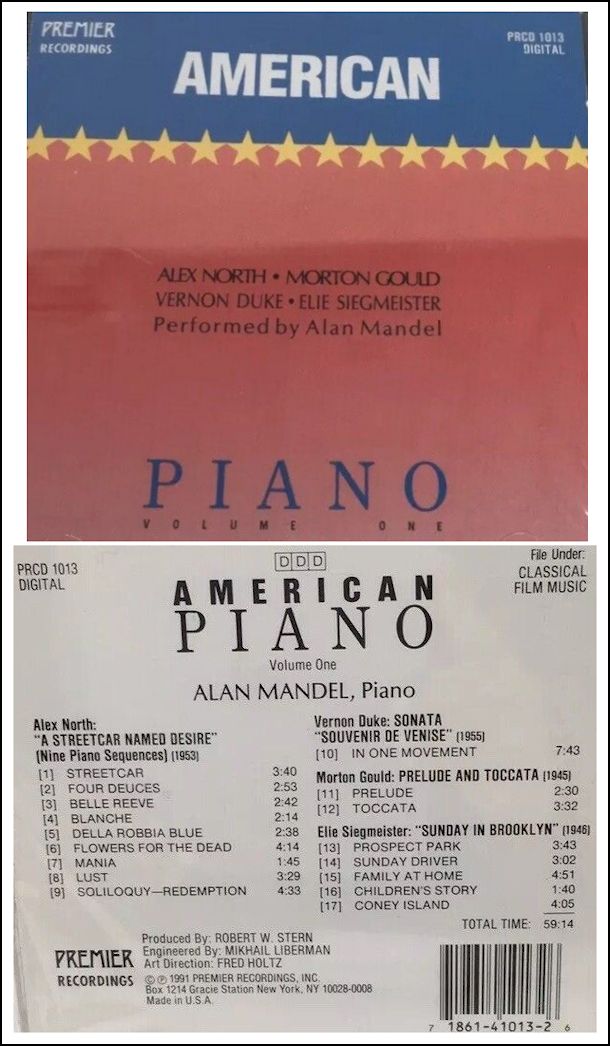

BD: Should it be labelled as ‘Ives

arranged by Mandel’? [Vis-à-vis the

recording shown at left, see my interview with Morton Gould.]

Mandel: No, Ives changed it himself. It’s

a different version done by Ives.

BD: But you’ve decided which changes you’ll use,

and which changes you’ll not use. It’s your

selection process.

Mandel: That’s right. Ives would have approved

of that. When he first worked on the ‘Concord’ Sonata with

John Kirkpatrick, who gave the first performance, Kirkpatrick said it was

particularly frustrating that sometimes he would play it for Ives, and

Ives would have a wonderful idea to change something, and he would give

him a new idea. There were many different ideas, and Ives thought of

his piece as never quite finished. They could always be changed and,

in my opinion, Ives was open to that sort of thing from everything that I’ve

read and everything I’ve been told.

BD: It sounds like a Chinese menu, with one from Column

A, one from Column B, and anything from Column C.

Mandel: [Laughs] What shall I say? They’re

all good, although one has to make a decision for one or the other.

I wouldn’t do that with other composers. Composers are different.

They’re all individuals, and they all have different temperaments

and difference preferences. For Elie Siegmeister, on the other

hand, I would play it exactly the way I thought it should be, and exactly

the way I worked on it with the composer.

BD: So then your recording of something of his

has a ring of truth to it because you worked on it with him?

Mandel: Oh, definitely! It makes a difference

to do that. On the other hand, it’s possible that some other performer

might have some necessity to perform it differently.

BD: Others shouldn’t slavishly imitate your

record all the time?

Mandel: Absolutely not! Every performer

is an individual.

BD: With the Ives, when you make the first decision,

does that influence all the rest of the decisions later in the piece?

Mandel: Yes, it could. With some Ives works

I’ve spent many years making decisions after great study. I found

some Ives pieces that were unpublished in manuscript, which, in my opinion,

are of the same quality as the ‘Concord’ Sonata. In Ives’s

manuscripts, his handwriting was worse than Beethoven’s, so it’s fantastically

difficult. It’s like hieroglyphics. It’s fantastically difficult

to decipher it, but with careful study you can. It takes a combination

of musicologists to decipher, and a pianist to play those particular pieces.

That doesn’t hold for the ‘Concord’ Sonata and the First

Sonata, which were published, as was the Three Page Sonata.

However, the ‘Concord’ Sonata was published in two different version,

both approved by Ives. The first is much earlier than the second.

I use the second version, which was the much later version. My recording

is quite different from that of John Kirkpatrick, who worked on it with

Ives. It’s perfectly valid, but I couldn’t do it that way because

I am me and he is he.

BD: Thank you for coming to Chicago, and for chatting

with me. I appreciate it.

Mandel: It’s a pleasure.

Notice that Mandel has recorded Volumes 1 and 3 of this series.

Notice that Mandel has recorded Volumes 1 and 3 of this series.

Volume 2 features pianist Ramon Salvatore.

© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 26, 1992.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1995 and 2000.

This transcription was made in

2025, and posted on this website at

that time. My thanks

to British soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here.

To read my thoughts

on editing these interviews for print, as

well as a few other interesting observations,

click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce

Duffie was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until its

final moment as a classical station

in February of 2001. His interviews

have also appeared in various magazines

and journals since 1980, and he now continues

his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more

information about

his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also

like to call your attention to the

photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive

field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and

suggestions.