Drew Landmesser

Technical Director (at the time of this interview

in 1998),

and later

Deputy General Director, and Chief Operating Officer

of

Lyric Opera of Chicago

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

It is noteworthy that in three specific instances, Lyric Opera

of Chicago has named its top-most officials from within its ranks. To

wit, in 1980, a former mezzo-soprano, turned typist, turned administrator

named Ardis Krainik

took over from the founder, Carol Fox, and became General Director. Later,

boy-soprano, turned administrator named William Mason acceded to

that position. The third member of this distinguished group is Drew

Landmesser. As you can see, he was the technical director, and now

(in 2021) is Deputy General Director and Chief Operating Officer.

In my conversation with her, Krainik said she had had, “The

longest apprenticeship in history,” by working within the company

all that time. Mason, on the other hand, worked with Lyric and other

companies before returning to Chicago. Landmesser followed that diverse

pattern, being in Houston and San Francisco before assuming his current

slot.

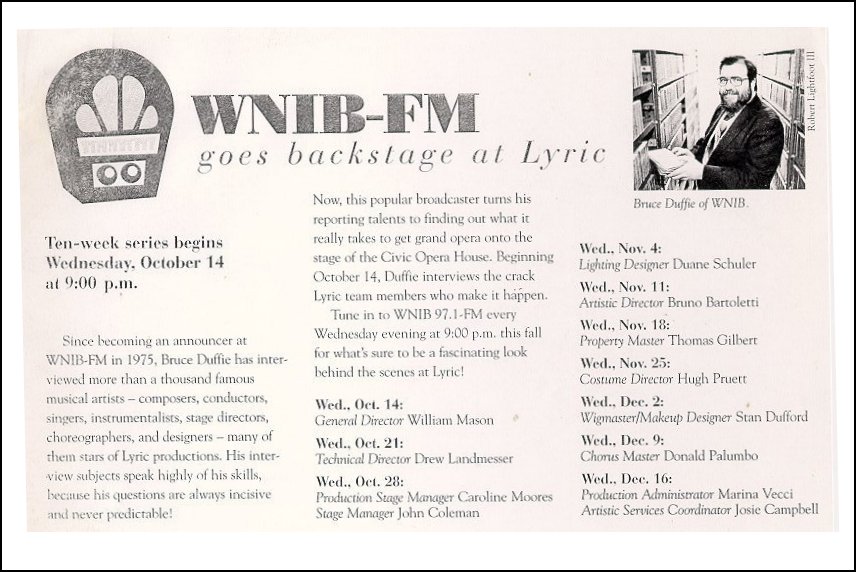

For my 1998 radio series presenting the backstage happenings

at Lyric Opera of Chicago (shown above), it was my pleasure

to interview several of the people who are generally unseen by the public,

but without whom the company would not be able to present Great Art night

after night.

Some of these people I was meeting for the first time, and

many of them were not used to speaking on the radio. It pleases

me that all of them quickly found it easy, and would converse with me

about their work. In the case of Landmesser, he made it clear at

the outset that he was a man of action . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: What is your title?

Bruce Duffie: What is your title?

Drew Landmesser: Technical director.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You direct

everything that is technical?

Landmesser: [Smiles] I direct nothing.

Titles don’t mean the same thing in lots of different companies,

but the jobs are similar in most places. I see through people.

I see through things, and we get it all done. We’re the

full-service technical department.

BD: Everything that is not musical comes

to you?

Landmesser: [Resolutely] Things that

need to get done come to us. If somebody needs a picture hung,

sometimes they come to us and sometimes we do that.

BD: If the tenor needs a high C fixed,

does he come to you?

Landmesser: They have to go

somebody else to get that fixed. There’s a higher authority. I

hate to admit that there's a higher authority...

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Higher

than the technical director???

Landmesser: Even higher than that.

BD: What are some of the typical things

that you will do, or is there a typical day?

Landmesser: There are typical days, but

they are full of a-typical things. In our little world, we deal

with very good people who all do their jobs and all know their jobs,

but they’re always being thrown curves. We

take care of scenery and props, and musical instruments arriving here

and moving there, and rehearsals being taped out on the floors, and

scenery moved from one room to another, and trucks that don’t

show up, and a warehouse that leaks. All that happens here, so

it’s just about anything. If you see it, we’ve had to deal with

it probably twice, or maybe more than twice.

BD: To use an operatic term, you’re like

the majordomo.

Landmesser: No, I’m much more soft-spoken

than he. He has a point of view. I just want to get it all

done.

BD: Do you want to get it all done right?

Landmesser: We only do it right. If

we don’t do it right, we don’t stay here. We do it right every night.

It’s what we do for a living.

BD: Do you ever get it right the first

time?

Landmesser: We live most of our life on

plan W. We don’t get it right the second time or the third time

because there’s too many things going on, even if you bring the show back.

For example, Traviata is a revival for us. It’s been

done. It’s been rented. It’s been very popular. It’s

been done in several other houses in the meantime, so when it comes back

to us it will be slightly different than it was when last we saw it.

Then, when it comes back again later this season with some of its

second cast, it will be different again. Things are always changing.

The only thing permanent in life is change.

BD: What kinds of things will be different

from the fall performances to the spring ones?

Landmesser: We live in a repertory house,

and what that means to the audience is that the third Friday of the

month they come and see Traviata. The next time they’re here,

they see Ariadne. The next time they’re here, they see Gioconda.

The next time they’re here, they see Meistersinger. But

for us, what it means is that at midnight when Meistersinger is

done, we go away and come back the next morning, and we tear it all apart,

and put up a show that’s not even performing that night. We put up

a show that’s just meant to be rehearsed, and we do that while annotating

everything that’s done along the way, so that when it comes time to do that

again, we put it together as fast as possible. We have an entire theater

season that happens without a single performer on stage, without a conductor,

and without an audience. We hire people to come in and walk through

the lights as though they’re the talent. We work seven days a week

from July until September doing nothing but technical and lightning work

around the shows that are to happen, because once we get to September, the

performers arrive, and the conductors arrive, and the orchestra shows up,

and there’s no time to fool around with those little nuances.

BD: You have to be done?

BD: You have to be done?

Landmesser: We’re done.

BD: But you have to do it again each time.

Landmesser: We’re done and we’re ready to

begin again, because nothing is permanent, but change. We’ll leave

the show assuming that the same person will come through the door on

the downbeat of the fourth line of the music on page forty-two, and that

they’ll slam the door on the next bar. But if they don’t when they

get here, we’ll change that, and then we’ll change the lights. The

stage managers will change the cue, and that will happen, and then the prop-guy

will come to catch the chair they throw at different times. All that

will change when slightly different things happen. When the cast

changes, different things happen, and when the director leaves town, many

different things happen.

BD: Should you tell the directors that?

Landmesser: They know that. Some

of them come back a month later just to check, but we’re there every

night checking. We have somebody from the lighting department, somebody

from the technical department, and the stage director’s assistant each

night who sit in the theater. We don’t sit actually in the theater

because we’re too rowdy to do that, but we sit in the back of the theater

making notes, and trying to make corrections if something goes wrong during

the show. Hopefully, no one ever sees anything go wrong, but if

something happens, we’re there with the staff to change that, and to adapt

to that, and to correct it for the following night.

BD: Is your allegiance to the stage director,

or to the conductor, or to the composer, or to the audience?

Landmesser: To the art. Our allegiance

is to the piece. I don’t say this disrespectfully, but sometimes

the director is gone, and something needs to be changed. Sometimes

something has to change.

BD: Just in order to make it work?

Landmesser: Just in order to make it work.

Maybe we could never make that exit work right, and now it needs

to work, and they figured that out. It might be two shows after

the director leaves, and it’s such a subtle change that maybe no one

notices, but we would take the opportunity then to call the director

and say we’re going to change this. Most often, we do things like

loose some smoke because the chorus and the principals hate smoke. There

are little things like that, but mostly just things to make sure they

work better.

BD: So, you’re constantly making sure they

work, but also making improvements?

Landmesser: Generally speaking, the things

that improve are musical, and in the ensemble, because the longer the

group stays together, the longer they work together, the more comfortable

they feel in the roles, which they can’t really feel comfortable with

by opening night.

BD: Even though they’ve been together for

six weeks?

Landmesser: Some of them have been together

for twenty years. They’re old friends. These people don’t

meet for the first time here. They know each other, and they pick

up where they left off. That is a remarkable thing about theater

people — we have people we don’t

speak to for ten years, but when they come in that stage door, it’s

like they were here last night at midnight, and now they’re here at eight

a.m. starting again. Friendships don’t end when someone leaves two

weeks after opening night. We’re always friends, and we’re always

colleagues, and we just keep going. So, things just keep maturing

and growing. They were changed in that they mature and grow.

* * *

* *

BD: How long have you been with Lyric Opera?

Landmesser: Forever. This is my eleventh

season. I came in June of ’87.

BD: Where were you before that?

Landmesser: I was in Houston from 1980

until ’87, with Houston Grand Opera.

BD: Doing what

— more technical directing?

Landmesser: I was the technical director

at Houston Grand Opera, and before that I was the technical director

at Texas Amphitheater. Then, the two merged.

BD: How does one train to be a technical

director?

Landmesser: Technical directors are different

in each company, and in some ways the company trains you to be what

they need you to be. Sometimes it is without words. There’s

a void in the company that needs to be filled, and the person fills it. Sometimes,

the personality fills it, and other times their expertise fills it. The

person’s expertise needs to grow to accomplish that.

BD: So, you have to fill it, or your position will

be filled with someone else?

BD: So, you have to fill it, or your position will

be filled with someone else?

Landmesser: No, you have to fill it, and

if you don’t quite know what to do, or if it’s something that you’ve

not experienced before, you still know what to do with that. Generally

speaking, you’re working with colleagues that are your friends, and

they are helpful. If you don’t have something, your friend has that

special something that they can bring to it. We work as a team.

I can’t do what I do without the master carpenter. If I can’t

do what I do, or he can’t do what he does, we turn to the head flyman.

If our prop man, Tommy Gilbert doesn’t show up for work one year, then

we’re all in trouble, and it’s because we are a team. We are a team,

and we work together. There’s no one person that’s the boss, and there’s

no one person that takes orders. If Tommy Gilbert tells me we

need to do something, and he’s right, we do that.

BD: It sounds like you coordinate everybody.

You have your finger on the pulse of everything that needs to

be done, and make sure that all of it does get done.

Landmesser: I like to make people talk to

each other because that’s how we get things done. What I do, how

I train, and what I know has more to do with talking to people. It

is what I’ve learned at school. I had wonderful mentors. When

I was in undergraduate school, my mentor was Klaus Holm. He was

the Broadway and opera designer that worked with Donald Oenslager, who designed

hundreds of operas and musical theater pieces in the ’50s

and ’60s. Hanya Holm was Klaus’ mom and

she worked with Mary Wigman. Hanya was one of the old dancer-influencers

in Germany, and was also an opera director. She was the original

director of Baby Doe, and worked in Central City a lot. Hanya

and Klaus influenced me greatly as I came to graduate school, and then

I got into the theater world. The opera world took me away from the

theater world, and this is where I got to Houston. Jean-Pierre Ponnelle

knew. We were best friends and great buddies. I did want to

leave Houston, but we just opened a brand new opera house down there, and

I spent four years with them. When Bill [Mason of Lyric Opera] called,

and when Dwayne Schuler,

[the lighting designer] called, it was all very tempting, but it was when

Jean-Pierre said that I should go there, I knew it was for me. We

had many good things we could do there together. Then Jean-Pierre

died that summer, so all the good things we were meant to do together we’ll

have to do some other time on the next stage, because in ten, or fifteen,

or twenty years, we’ll still be friends.

BD: [Mildly concerned] You don’t

see yourself living beyond that?

Landmesser: I just live hoping my life

continues. Seasons blend. I don’t know how long I’ve been

here, and I don’t know how long any of us have been here. We just

always have been here, and we’ll always be here. Jean-Pierre is

still with me, and he’s still with Bill. He influences everything

we do, just as Solti

will at the Chicago Symphony. There are people that will influence

you forever, and maybe someday we’ll influence somebody else with what

we do.

BD: I hope so. Do you feel that you

influence the audience by getting all of these things done, so that

it’s presented each night for 3,600 people?

Landmesser: We try not to think of it in a

personalized way, but in a team way. I have to believe we influence

what the audience sees. We want them to see something that is so

polished, so clean, so professional that it’s unlikely. When they

see Phantom and they can see into the wings, they can see things

happening. They see something wiggling, or they see something askew.

For us, that’s hard on the tenth performance of an opera that

opened a month and a half ago. It’s hard because in the meantime

you’ve rehearsed and opened three other operas. There’s a lot of

work going on on the stage, with what’s hanging in the air, what’s sitting

in the wings, what’s being rehearsed, what’s marked, where the lights were

focused before, and so forth. It is hard to keep re-creating that,

because it’s a new show every time. It’s not like some theater

or opera house where you have one opera on stage, and it’s been there for

two months. That’s a very easy show to put on stage because it

never moves, it never wiggles.

BD: Would it be easier to do something

like Phantom, which runs eight times a week?

Landmesser: It would be easy and it would

be mind-numbing. I think that’s what purgatory must feel like. I

mean no disregard for Mr. Lloyd-Webber, but not only is the music not

what I’d like to hear for the rest of my year, but it’s the same mood

over and over and over again. What’s exciting about what we do is

that every day is a different challenge. It’s the same piece of Gioconda

that has to move to that same place on the mark on the floor in the third

act, but what’s in the way today is a little piece of Ariadne that

wasn’t there when we opened the show. Ariadne comes and

goes, and then Gioconda goes, and then something else affects

Ariadne. It’s a constant challenge.

* * *

* *

BD: You mentioned the music. You’re

involved in technical stuff, so do you get involved in the music at

all?

Landmesser: Of course I’m involved. We

all are involved in the music. If you take it at the most simple

level, there’s music that covers a scene change.

BD: How loud is that music?

Landmesser: We better get it done under

it. If we are making too much noise, we better tell the guys to

move that piece in a different way. The guys have to pick that piece

up and carry it, rather than drag it. Or, we don’t use a hammer for

this scene change. If there is no time for the steel curtain to

come down, the music effects everything you do, but mostly what it affects

is it affects your spirit. We have stagehands here who are not

typical stagehands. These are people that love the opera. You

can have stagehands that will make their change, and then will go and finish

the book that they started, or work on a crossword puzzle. But some

of them will sit in the wings and listen to the aria that’s about to be sung,

and their jaws drop as far as ours because it’s beautiful. How can

you not be affected by it? That’s the reason why most of us are here.

It’s not just the scenery, and the fact that the scenery here is fifty

feet tall as opposed to twenty feet tall someplace else. A single

piece generally will weigh ten thousand or twenty thousand pounds, as opposed

to something weighing just two hundred pounds. When you stand there

and watch what’s going on, you listen to it. You take the time to

take it all in, like the audience member is taking it all in. There’s

something spectacular and moving going on in every one of us.

BD: Does this at all influence who you

hire — someone who really likes

the opera, rather than someone who doesn’t care about the opera?

Landmesser: It influences who stays here.

It is clearly their choice, but they can’t make it through a season

unless they really like it. The proof of that is that so many people

end up in relationships with some of the other people who are in the same

business. Maybe that’s because you only ever get to meet those people,

but we have stagehands that are married to choristers. We have ballet

people married to ballet people. We have choristers married to choristers,

and I’m sure there are other relationships we can’t mention because we don’t

know about them, or don’t want to know about. But the thing that

hold us all together is that this art form is the most magnificent art

form. You can go to the Chicago Symphony and have beautiful music,

but there’s nothing else going on besides the beautiful music. They

try to do these little things in concert, and they try to make it look like

they are as good as we are, but this is an art form to beat the band. I

mean no disrespect, but here you have ballet, you have dance, you have

movement, you have color and light and scenery and costumes and props.

Sometimes you even catch the smell of what’s going on on stage. It’s

just like Chicago is different than New York. New York smells like

garbage and urine, while Chicago smells like chocolate! That’s

what makes Lyric different from the CSO. The symphony is fabulous,

but Lyric smells and lives that. When you walk out of Lyric, you’ve

experienced that moment in that person’s life. Pagliacci

lived in you for a moment. When you come out of the CSO, you’ve

been impressed by the music, and the power of the music. Here, you’ve

lived it. If you don’t come out of here some nights weeping, we

need to change the genre. For the opening cycle of the Ring

I sat in the house, which is the first time I’ve done that in about ten

years. I felt the whole audience with me, holding their breath for

a moment. You couldn’t let your body make any noise to interrupt the

sound, or the thing that was happening on stage in front of you, because

it’s just way too powerful.

BD: [Somewhat surprised] Are

you not needed backstage once the curtain goes up?

Landmesser: What would I do? What could

I do that the crew couldn’t do better? If something happens backstage,

I run. That’s one of the reasons why I usually sit in the booth

at the back of the theater with my staff. We all sit in booths

so we can make quick escapes. We don’t want to even sit by the aisle,

and have to go through the door because this is disrupting. We sit

in the booth in the back where we can hear it, we can see it, and we’re

witness to it. I confess to having blasted through the door to

run backstage as fast as I can, but there’s very little that the crew

has not already taken care of by the time I get back there. But

usually, it’s just personal excitement that I run back there for.

BD: Is there ever a night when everything just

goes right?

Landmesser: There are many nights

when everything just goes right. There are some nights that are

just too beautiful to describe. You know what I mean. How

lucky can a person be to be able to work here and be repeatedly exposed

to those nights? Sometimes we’d sit there in Susannah [shown

at right, with Samuel Ramey and Renée Fleming],

and it’s just the music, the sound; or to be enveloped by the Ring Cycle

and to live through it. I imagine the audience members at that

time, and how much they must have felt of the excitement in the moment,

and the joy of the music, and the sights and sounds, and what was going

on, and how exciting it must have been. That’s like the father’s

joy of the birth of a child. We, on the other hand, experience

the mother’s nine months of labor, because we had four years of labor

bringing that child to the stage. So, on some nights, what’s gone

right is that a year before has gone into getting it there. Some teams

work so well together. I can’t even tell you how many beautiful moments

I’ve sat in the theater without an actor, or a singer, or an orchestra.

Even those moments were beautiful. We’d make a scene change in a

rehearsal six months before the cast would arrive, and something so beautiful

would happen. Maybe you’d never get to re-create that. There

are some times when, after the audience is emptied and the crew goes to

strike the set and get ready for the next day or that night, they’ll take

out the fire curtain [seen in the photo below-right], they take out

the house curtain, they’ll take out one of the sound doors in the back,

and they’ll open the doors to find maybe a trailer is backing in off of

Washington Street. You can see clearly through one entire block of

Wacker Drive, and the sound comes blasting through the middle of that. It’s

beautiful. I’ve never shared that to anybody else. These are good

times and good people. This is a great place to work.

Landmesser: There are many nights

when everything just goes right. There are some nights that are

just too beautiful to describe. You know what I mean. How

lucky can a person be to be able to work here and be repeatedly exposed

to those nights? Sometimes we’d sit there in Susannah [shown

at right, with Samuel Ramey and Renée Fleming],

and it’s just the music, the sound; or to be enveloped by the Ring Cycle

and to live through it. I imagine the audience members at that

time, and how much they must have felt of the excitement in the moment,

and the joy of the music, and the sights and sounds, and what was going

on, and how exciting it must have been. That’s like the father’s

joy of the birth of a child. We, on the other hand, experience

the mother’s nine months of labor, because we had four years of labor

bringing that child to the stage. So, on some nights, what’s gone

right is that a year before has gone into getting it there. Some teams

work so well together. I can’t even tell you how many beautiful moments

I’ve sat in the theater without an actor, or a singer, or an orchestra.

Even those moments were beautiful. We’d make a scene change in a

rehearsal six months before the cast would arrive, and something so beautiful

would happen. Maybe you’d never get to re-create that. There

are some times when, after the audience is emptied and the crew goes to

strike the set and get ready for the next day or that night, they’ll take

out the fire curtain [seen in the photo below-right], they take out

the house curtain, they’ll take out one of the sound doors in the back,

and they’ll open the doors to find maybe a trailer is backing in off of

Washington Street. You can see clearly through one entire block of

Wacker Drive, and the sound comes blasting through the middle of that. It’s

beautiful. I’ve never shared that to anybody else. These are good

times and good people. This is a great place to work.

BD: Would you ever want a composer to call

for that effect in a scene of his new opera?

Landmesser: You could call for it, but

I don’t know if you can do it. It’s hard to get the same thing

to happen two nights in a row. That’s the goal, but it’s hard

to do that. It’s hard to hit a high C two nights in a row.

BD: That’s right, but that’s what they’re

paid the big bucks to do.

Landmesser: That’s what they love to do.

They take the big bucks just because you give it to them. That’s

why we do it. I swear to God, I haven’t opened a pay stub in ten

years. I just trust that they’re paying me. I know that I’m

here because of what I do, not because of what they’re paying me.

BD: You deposit the check and don’t look

at the total?

Landmesser: It’s an online deposit, and

I haven’t looked at it in 10 years. [Pauses a moment] I hope

they’re paying me...

BD: I’m sure you would find out immediately

from your creditors.

Landmesser: [With a smile] Somebody

would have known. Somebody would have told me.

BD: The feeling I get from everyone is

that it’s a joy to work here. They’ve worked here for years and years,

and amazingly, yours is one of the shortest careers here.

Landmesser: I am, and it just means I have

a long time to go.

BD: I assume you’re looking forward to being

here for 20, 30, 40 years.

Landmesser: Oh, boy...

BD: [Slyly] Should I tell everyone

there was a look of abject terror on your face?

Landmesser: No. You shouldn’t tell the

terror. We don’t look at calendars the same way. The Lyric’s

calendar doesn’t even begin on a Sunday like everybody else in the world.

We begin on a Monday, because that’s when all the union contracts

begin. The union contracts for the orchestra, the stagehands, and

everyone all begin on Mondays. We don’t keep track of time the same

way. I guess we’re closer to an academic year than a calendar year.

If you ask me when my son was born, it was at 12:30 in the morning

on the night of the first day of the Salome rehearsal in 1988. Now,

what the heck that means to anybody else I don’t know, but we gauge the experiences

in our life by what was on stage at that time, not by the year, or the

day, or the season. [Note: BD’s

second marriage took place on the day of the Met broadcast of Elektra

with Birgit Nilsson,

Leonie Rysanek, Mignon Dunn, and James Levine.] Half

the stagehands here don’t get to see their house from the time the leaves

are green until the time the leaves are gone, because somebody else is

raking them up.

BD: Since you’re here all year round,

you don’t guest at other houses?

Landmesser: No. You visit other houses

during the shows, or in meetings, but I don’t guest in another house.

BD: When you go to another house, do you look

to see things that you’d like to do here, or things you want to be sure

never to do here?

Landmesser: Yes. There are

some very good houses, and there are always things to notice. Maybe

they’re not even aware that there are things that are meant to be taken

from those houses, but there are wonderful houses here and there and

everywhere. There are some unfortunate things going on in the world

of opera right now, but there are also some great things going on.

Landmesser: Yes. There are

some very good houses, and there are always things to notice. Maybe

they’re not even aware that there are things that are meant to be taken

from those houses, but there are wonderful houses here and there and

everywhere. There are some unfortunate things going on in the world

of opera right now, but there are also some great things going on.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future

of opera?

Landmesser: I’m a pessimist. I’m not

an optimist, so that’s a hard question. The future of opera is not

dependent on what I can do to help it. I can only make this the

most perfect event for the viewer, the most exciting, the most relaxing,

the most entertaining evening that I can bring to them, and I depend

on the five hundred people who feel the same way as I do, from David,

the guy that empties the trash cans backstage, to Sam Ramey. We

all have to feel that same way about it, but frankly, will Kraft be

generous to us next year? Will Aon be generous to us next year?

Will American Airlines be generous to us next year? Those

are the reasons why we’re still going to be here. We’re going to

have to get it from the government. We’re not going to be able

to support it by ourselves. We depend on the generosity of others

to make it really happen. What we can do is fight to maintain the

quality of what we put onstage. People respect us enough to come back

year after year after year after year. We are now ten years with

over 100% of tickets sold. [With a wink] How long have I been

here?

BD: [With mock sincerity] You’re

talking full credit for that???

Landmesser: [Laughs] Maybe it’s

a coincidence, but I’d like to think that people come back because

I do my job as well as I can, and people that work with me do their

jobs as best as they can, because the guy that sees the show on the tenth

performance deserves to see the same show as the guy who sees the first

show of that run.

BD: I would think the first show would

not be quite as good as the third or fourth show.

Landmesser: From an ensemble’s point of

view, or from the orchestra’s point of view, that might be the case,

because they can get a little bit more polished. Certainly, there’s

an excitement about that opening night, but maybe they can work on their

blending a little bit, or fix that musical note here, or a passage there.

After meeting with the maestro, and having sung these two or three

performances, they realize that if they attack this a little bit differently,

or take a breath there, that they can do something even better. But

for the orchestra, maybe in the middle of the run of Mahagonny, they

might’ve had twelve hours of Meistersinger rehearsals, and the brass

has been blowing their brains out. It’s hard, and they’ll come back

that night and do Ariadne or Traviata beautifully after they’ve

been pounding away at something else. It’s the

same for us. In the week before we open a show, we spend extensive

hours working on that show, to make sure scene changes go as tight as possible,

making sure that a piece of scenery passes or lands exactly where it’s

supposed to land, and the prop comes there, and the light change happens

there. We make sure all those are coordinated beautifully. Then,

either the night after the dress rehearsal, or the morning following

the dress rehearsal before the opening of that show, another show will

land on the stage that hasn’t ever been there, and that affects me. A

naturalist would tell you that you can’t walk into the forest and view

the animal life without affecting the animal’s behavior. Neither

can one opera coming on stage not make an effect. It affects the show

before, and it affects what goes on here. So, we have to just make

that transparent so that no one in the audience can know it. No one

in the audience can know that for four months, people will enter from stage-left,

but now they must enter from stage-right. Some piece of scenery is

now there and we can’t get rid of it. It is too big, so it has to

stay there, but the audience can’t know that. You know that, but

they can’t.

* * *

* *

BD: What one or two shows were the easiest

to get up, that just flowed immediately?

Landmesser: The ones I did when I first got here. Shows

are getting harder and harder and harder. Shows that seem easy

are not always easy. In the repertoire, sometimes we would take

a show that’s either physically less demanding, or less demanding to the

chorus or the orchestra, and stick it between two shows that are very,

very difficult so that you have a little breathing room. However,

the restraint you put on that easy show can make it just as hard as the

hard shows. We have a beautiful Barber of Seville that John

Conklin gave us [shown in photo at right] that came us to us in

a roundabout way, because we were supposed to do a different production.

For that production, the costumes caught on fire, and we ended up building

a new production. It’s a wonderful little production, but it’s very

tricky. It’s got a lot of little bits and pieces that have to be done

really well. But it’s small, and we thought that would maybe be the

key to what’s still easy to do. We also did a pretty big renovation

of the opera house a few years ago. They doubled the space on stage

to store props and scenery, and made great rehearsal opportunities and facilities.

It also changed the lighting around a lot. But in general,

scenery keeps getting bigger and bigger. It’s more and more real.

It’s three-dimensional. There’s very little painted scenery

anymore. If there’s any painted scenery, it’s way upstage, and everything

in front of us now becomes very real. The big pieces of scenery

are impossible to store, so shows that are small are easy shows, just because

they’re small.

Landmesser: The ones I did when I first got here. Shows

are getting harder and harder and harder. Shows that seem easy

are not always easy. In the repertoire, sometimes we would take

a show that’s either physically less demanding, or less demanding to the

chorus or the orchestra, and stick it between two shows that are very,

very difficult so that you have a little breathing room. However,

the restraint you put on that easy show can make it just as hard as the

hard shows. We have a beautiful Barber of Seville that John

Conklin gave us [shown in photo at right] that came us to us in

a roundabout way, because we were supposed to do a different production.

For that production, the costumes caught on fire, and we ended up building

a new production. It’s a wonderful little production, but it’s very

tricky. It’s got a lot of little bits and pieces that have to be done

really well. But it’s small, and we thought that would maybe be the

key to what’s still easy to do. We also did a pretty big renovation

of the opera house a few years ago. They doubled the space on stage

to store props and scenery, and made great rehearsal opportunities and facilities.

It also changed the lighting around a lot. But in general,

scenery keeps getting bigger and bigger. It’s more and more real.

It’s three-dimensional. There’s very little painted scenery

anymore. If there’s any painted scenery, it’s way upstage, and everything

in front of us now becomes very real. The big pieces of scenery

are impossible to store, so shows that are small are easy shows, just because

they’re small.

BD: You say the scenery is real. Is

opera real?

Landmesser: Am I real? Yes, opera is real.

Why it would not be real? If you go to the theater, you’re

supposed to suspend disbelief. You come to the opera, and we’re

required to make you forget that you’re disbelieving. We take you

in. We pull you. We trick you. It’s not like a circus.

It’s not like a soap opera. It’s like a really, really good

book. Charles Dickens writes stories that aren’t

real, but are they fiction? Who cares? Maybe the circumstances

aren’t real, but maybe they are. When Violetta dies, are you not

moved by that? That’s a real emotion. So, that’s real. To

me, that’s real. It’s always real.

BD: What show has been the most difficult for you?

Landmesser: We’ve had a couple of difficult

individual shows. Un Re in Ascolto [by Luciano Berio] was quite

involved. Ghosts of Versailles [by John Corigliano] was

quite involved. Rake’s Progress [by Igor Stravinsky] was

quite involved.

BD: Is that because these are relatively

new operas, or just because of their complicated staging?

Landmesser: Both. In the case of Ghosts

of Versailles, the composer and the director and the designer had

impossible requests to make. Colin Graham and John Conklin came

up with some solutions for that. They’re flipping through generations

and locations like [snaps fingers]. Whoa! Time warp. But

you do it through the magic of the theater. You’re not moving from

here to there, but you are moving from here to there. Then,

you begin to forget a couple of things. You’re not hampered by

thoughts of not really being there. You take it for granted, and

you go there. The Magic Flute is not exactly new, but it

is pretty tough if you get enough animals on stage. By far, and

specifically for Chicago, I think the Ring Cycle was the hardest

thing I’ve ever done, and not just because it’s the

Ring Cycle. We began playing it and planning the renovation

almost at the same time. The Ring Cycle was essentially a

unit set. Each of the four operas happened within the same environment,

and yet we did plan it knowing that six years from then, when we finally

got to put it together, that on a Monday morning we’d be rehearsing

Act One of Walküre, and that afternoon we’d be rehearsing Act

Two of Götterdämmerung, and in the evening we’d be

rehearsing Siegfried. To flip back and forth among those operas

is hard. Then, imagine in the middle of creating all of those shows

that everything from your stage floor to your curtain to the window above

you, everything you’ve touched, everything you felt in that space, every

light in the building, every electrical circuit, every doorway, every

particle backstage has changed. It didn’t change overnight, and

it didn’t change all in one summer. It changed gradually, one after

another. So, even when we bring back something that we’ve done

the year before, the basic set was in a different place in a different

way. That was fun. That was great fun.

BD: Do you look at every new show that comes in as

a challenge?

BD: Do you look at every new show that comes in as

a challenge?

Landmesser: Yes, but some more than others.

That’s what makes my life great. That’s what makes my job great.

It’s like every day is starting over again. Some days you

win, some days you don’t, and I know that the fellows on stage and the

rest of my staff feel the same way. Some days you really get a

lot of accomplished, so you get that and you grab it and you win.

Then some days you fail miserably, but you have another day, and after

that you have another day. Or, if not, you have a lesson you’ve learned

for the next show. As any of us who have been around here for many

years can tell you, there are things that you just know. Then, you

see something new. A young designer will come up, or a young director

will come up and say they’d like to do this. You swallow hard because

you know that it’s wrong, but you’re part of their support. You’re

part of what makes their vision come to the stage. So, you try that.

BD: Wouldn’t it be better to save them

a lot of pain and discovery-time?

Landmesser: That would be naïve. No,

it’d be worse than that. That would be being stodgy, because their

brilliance is in the discovery. What if he’s right? I’d rather

spend a little time trying to make it happen, or taking what I know and

taking what he wants to try to make it happen.

BD: I assume there are at least a few times

that you do find that it does work.

Landmesser: Yes, or they would have fired

me by now. It’s the fresh blood, and it’s

their blood that makes us great.

BD: Thank you for being part of it. I hope

you’re here for a long time to come.

Landmesser: Okay. Thanks.

========

========

========

---- ---- ----

======== ========

========

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 10, 1998.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following month, and again

in 1999. This transcription

was made in 2021, and posted on this website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie

was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in

various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues

his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews, plus a full

list of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

Bruce Duffie: What is your title?

Bruce Duffie: What is your title? BD: You have to be done?

BD: You have to be done? BD: So, you have to fill it, or your position will

be filled with someone else?

BD: So, you have to fill it, or your position will

be filled with someone else?

Landmesser: There are many nights

when everything just goes right. There are some nights that are

just too beautiful to describe. You know what I mean. How

lucky can a person be to be able to work here and be repeatedly exposed

to those nights? Sometimes we’d sit there in Susannah [shown

at right, with Samuel Ramey and Renée Fleming],

and it’s just the music, the sound; or to be enveloped by the Ring Cycle

and to live through it. I imagine the audience members at that

time, and how much they must have felt of the excitement in the moment,

and the joy of the music, and the sights and sounds, and what was going

on, and how exciting it must have been. That’s like the father’s

joy of the birth of a child. We, on the other hand, experience

the mother’s nine months of labor, because we had four years of labor

bringing that child to the stage. So, on some nights, what’s gone

right is that a year before has gone into getting it there. Some teams

work so well together. I can’t even tell you how many beautiful moments

I’ve sat in the theater without an actor, or a singer, or an orchestra.

Even those moments were beautiful. We’d make a scene change in a

rehearsal six months before the cast would arrive, and something so beautiful

would happen. Maybe you’d never get to re-create that. There

are some times when, after the audience is emptied and the crew goes to

strike the set and get ready for the next day or that night, they’ll take

out the fire curtain [seen in the photo below-right], they take out

the house curtain, they’ll take out one of the sound doors in the back,

and they’ll open the doors to find maybe a trailer is backing in off of

Washington Street. You can see clearly through one entire block of

Wacker Drive, and the sound comes blasting through the middle of that. It’s

beautiful. I’ve never shared that to anybody else. These are good

times and good people. This is a great place to work.

Landmesser: There are many nights

when everything just goes right. There are some nights that are

just too beautiful to describe. You know what I mean. How

lucky can a person be to be able to work here and be repeatedly exposed

to those nights? Sometimes we’d sit there in Susannah [shown

at right, with Samuel Ramey and Renée Fleming],

and it’s just the music, the sound; or to be enveloped by the Ring Cycle

and to live through it. I imagine the audience members at that

time, and how much they must have felt of the excitement in the moment,

and the joy of the music, and the sights and sounds, and what was going

on, and how exciting it must have been. That’s like the father’s

joy of the birth of a child. We, on the other hand, experience

the mother’s nine months of labor, because we had four years of labor

bringing that child to the stage. So, on some nights, what’s gone

right is that a year before has gone into getting it there. Some teams

work so well together. I can’t even tell you how many beautiful moments

I’ve sat in the theater without an actor, or a singer, or an orchestra.

Even those moments were beautiful. We’d make a scene change in a

rehearsal six months before the cast would arrive, and something so beautiful

would happen. Maybe you’d never get to re-create that. There

are some times when, after the audience is emptied and the crew goes to

strike the set and get ready for the next day or that night, they’ll take

out the fire curtain [seen in the photo below-right], they take out

the house curtain, they’ll take out one of the sound doors in the back,

and they’ll open the doors to find maybe a trailer is backing in off of

Washington Street. You can see clearly through one entire block of

Wacker Drive, and the sound comes blasting through the middle of that. It’s

beautiful. I’ve never shared that to anybody else. These are good

times and good people. This is a great place to work. Landmesser: Yes. There are

some very good houses, and there are always things to notice. Maybe

they’re not even aware that there are things that are meant to be taken

from those houses, but there are wonderful houses here and there and

everywhere. There are some unfortunate things going on in the world

of opera right now, but there are also some great things going on.

Landmesser: Yes. There are

some very good houses, and there are always things to notice. Maybe

they’re not even aware that there are things that are meant to be taken

from those houses, but there are wonderful houses here and there and

everywhere. There are some unfortunate things going on in the world

of opera right now, but there are also some great things going on. Landmesser: The ones I did when I first got here. Shows

are getting harder and harder and harder. Shows that seem easy

are not always easy. In the repertoire, sometimes we would take

a show that’s either physically less demanding, or less demanding to the

chorus or the orchestra, and stick it between two shows that are very,

very difficult so that you have a little breathing room. However,

the restraint you put on that easy show can make it just as hard as the

hard shows. We have a beautiful Barber of Seville that John

Conklin gave us [shown in photo at right] that came us to us in

a roundabout way, because we were supposed to do a different production.

For that production, the costumes caught on fire, and we ended up building

a new production. It’s a wonderful little production, but it’s very

tricky. It’s got a lot of little bits and pieces that have to be done

really well. But it’s small, and we thought that would maybe be the

key to what’s still easy to do. We also did a pretty big renovation

of the opera house a few years ago. They doubled the space on stage

to store props and scenery, and made great rehearsal opportunities and facilities.

It also changed the lighting around a lot. But in general,

scenery keeps getting bigger and bigger. It’s more and more real.

It’s three-dimensional. There’s very little painted scenery

anymore. If there’s any painted scenery, it’s way upstage, and everything

in front of us now becomes very real. The big pieces of scenery

are impossible to store, so shows that are small are easy shows, just because

they’re small.

Landmesser: The ones I did when I first got here. Shows

are getting harder and harder and harder. Shows that seem easy

are not always easy. In the repertoire, sometimes we would take

a show that’s either physically less demanding, or less demanding to the

chorus or the orchestra, and stick it between two shows that are very,

very difficult so that you have a little breathing room. However,

the restraint you put on that easy show can make it just as hard as the

hard shows. We have a beautiful Barber of Seville that John

Conklin gave us [shown in photo at right] that came us to us in

a roundabout way, because we were supposed to do a different production.

For that production, the costumes caught on fire, and we ended up building

a new production. It’s a wonderful little production, but it’s very

tricky. It’s got a lot of little bits and pieces that have to be done

really well. But it’s small, and we thought that would maybe be the

key to what’s still easy to do. We also did a pretty big renovation

of the opera house a few years ago. They doubled the space on stage

to store props and scenery, and made great rehearsal opportunities and facilities.

It also changed the lighting around a lot. But in general,

scenery keeps getting bigger and bigger. It’s more and more real.

It’s three-dimensional. There’s very little painted scenery

anymore. If there’s any painted scenery, it’s way upstage, and everything

in front of us now becomes very real. The big pieces of scenery

are impossible to store, so shows that are small are easy shows, just because

they’re small. BD: Do you look at every new show that comes in as

a challenge?

BD: Do you look at every new show that comes in as

a challenge?