Composer Robert Kritz

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Chicago composer and WWII Veteran, Robert Kritz

(born November 20, 1925), died peacefully April 14 at the age of 92. "His

life was a tapestry of sonatas, adventure, art, life-long learning and family

-- especially children," said his long-time companion, Georgeanna Fischetti.

Although he spent much of his adult life in marketing, including running

Robert Kritz and Associates, Bob came into his own after retirement when

Georgeanna urged him to return to his music. His compositions, including

"Connections" and "Diaspora Dances" were played across Europe, South America

and the US.

He is survived by Georgeanna, his 3 children, Harold Kritz, Angie Atkins

(and husband Norman) and Daniel Kritz (and wife Susan), Joe and Paul Dunfee,

and many loving grandchildren.

== Chicago Tribune, April 20, 2018.

|

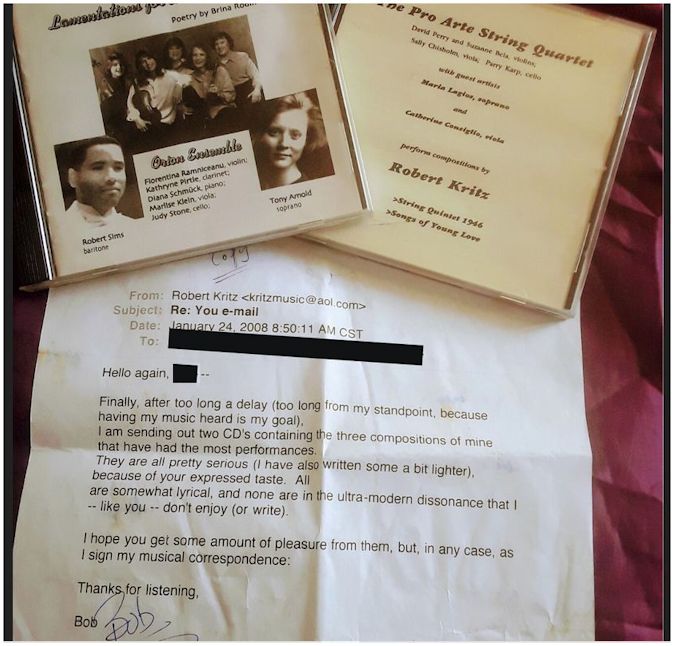

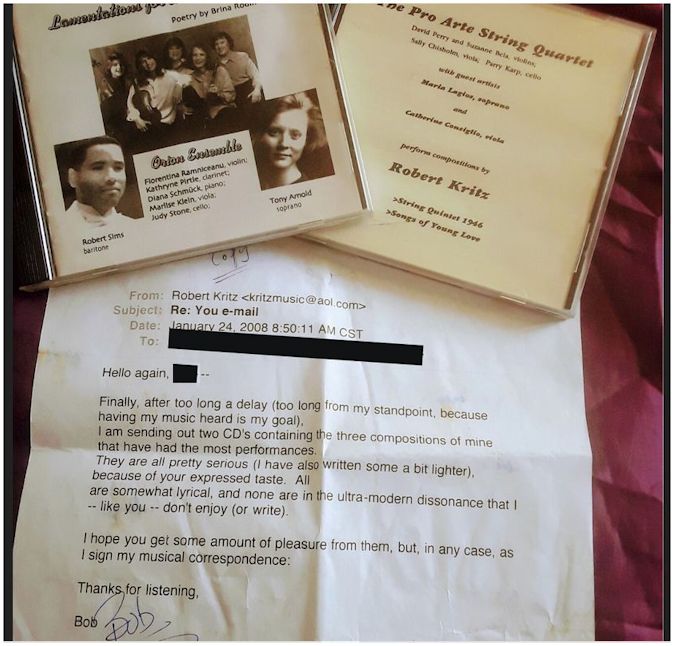

In Mid-June of 1998, it was my pleasure to meet with Chicago composer

Robert Kritz for an interview. He was re-establishing himself in the

concert music world after having spent much of his life in business. A

few of his works were being performed, and he was very enthusiastic about

having his musical ideas brought forth.

I was able to produce a program featuring recordings of his pieces

and part of this conversation on WNIB, Classical 97, and now, a few months

prior to his centenary, the entire chat is presented on this webpage . .

. . .

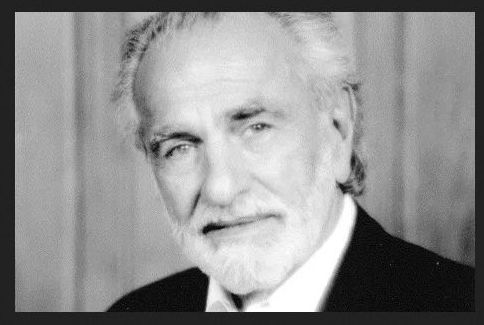

Bruce Duffie: My first question is about the

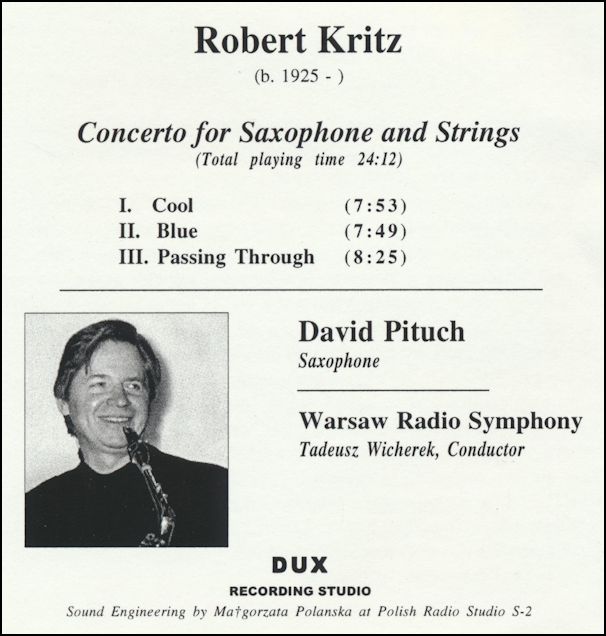

program note for your Saxophone Concerto. It lists you as

a businessman. Why does it not list you as a composer?

Robert Kritz: I was a composer for the first

ten years of my twenties, and then personal problems arose which forced

me to go back into the commercial marketplace.

BD: You needed cash?

Kritz: I had debts.

BD: A lot of composers will teach or perform,

and you decided to go back into business?

Kritz: At the time, that was the avenue which

was most open to me. I didn’t have the qualifications to go into

teaching, and the path I chose seemed the easiest for me to pay my debts

with.

BD: Being a composer who is then in business,

were you able to influence some non-musicians to come to concerts, and

get them interested in music both old and new?

Kritz: My mission then was just to try to

keep as much involved in music as I could, while continuing to earn a

living. So I studied and composed at night, and played some chamber

music. The job of trying to spread the word didn’t occur to me

until much later when I finally decided to come back into music after

a commercial career.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] When you

were in business, you were just that crazy guy who composes at night?

Kritz: [Laughs] That’s right, and I

kept it to myself pretty much. Once a week, we would play some chamber

music, and once in a while they would dabble with something I had written.

But mostly it was just to keep in it, and not give it up completely.

BD: When were you able to give up the business

and go back into composing full-time?

Kritz: Three years ago I saw that I was soon

going to be seventy, and the question I had asked back in my twenties

and early thirties was whether this music I’d written have any value?

That question just continued to gnaw at me, and if I was going to

find out, it better be now. So I decided to leave the business and

take a chance. I went to Northwestern where I had studied fifty years

ago, and went to see Dean Richard Green. He’s the man to whom I

owe the first real debt for not laughing at me when I showed him a fifty-year-old

manuscript that was yellow. He really studied it, and called in some

of the other composition instructors and professors.

BD: Is this not to say that you changed your

styles or ideas in fifty years, or where you looking to pick up where

you had left off?

Kritz: I was hoping to pick up where I had

left off, but I wanted to know if the path was worth continuing.

I needed some kind of validation.

BD: Before you asked for this new advice,

did you feel that it was valid?

Kritz: Yes. I felt there was some merit

to a couple of the pieces. They had been performed fifty years

ago to some degree of success, and I thought that if I could remember the

melodies after fifty years, there must be something worth saving.

After hearing the music at several performances, what I discovered was

that it did need some tightening and some structuring, but that the material

on which it was built, did have some merit. I felt comfortable with

that, but it took an awful lot of work to get it into shape. This

was work which I didn’t follow through on fifty years ago, but when I picked

it back up in 1995, Green had a few things to suggest. I was then

to bring it back and he’d arrange for a reading. I was flabbergasted

that I was given that much encouragement, but I did as he suggested. When

I brought it back, they gave it a reading, and pretty soon set up a masterclass

for credit of some five string players at Northwestern that were in the

Master’s program. Their job was to analyze, rehearse and then perform

this Quintet.

BD: Were you pleased with what you heard?

Kritz: I was pleased, but as we were getting

into it, I could see that it did need that tightening.

BD: They played it before you had actually

tampered with it?

Kritz: They played it for an entire semester.

I had tampered with some details, but as the rehearsals continued, I

saw that it needed more tightening, more structure.

BD: [With a wink] I hope you didn’t

get it down to the size of a Webern piece.

Kritz: [Laughs] No, no, no! It

ended up being thirty-five minutes, so I hope it still has a great deal

of breadth and depth.

BD: Does it still have a great deal of you?

Kritz: I’m glad you asked that, because that’s

really what we’re after. When you write something, or paint, or

work in any art form, it’s got to speak for you. It has to sing your

song, and it did. Then, the next challenge is to make that song listenable

and accessible. What I had to say is important to me, but I want to

make it somewhat important to you, and that takes a skill which doesn’t

come by itself, except to a very few, like perhaps Mozart. It takes

real work. Finally, after five or six sets of revisions, and twelve

performances by various chamber music groups, I got to where I think it

says what I want to say. It tells you my song!

BD: Is this the only song you have in you,

or do you have more songs?

Kritz: [Laughs] Yes, I have more, and

I’m working on several. The String Quintet was the first

that I brought back to life from the 1940s, and it’s received a good

deal of notice, and many performances. The Pro Arte Quartet, the

quartet-in-residence at the University of Wisconsin, has put it into

their repertoire, and that’s more validation than I ever dreamed I’d

receive when I started. In the meantime, I’ve worked on other pieces.

The Northwestern group performed it on the Dame Myra Hess Memorial

Concert Series, and it was heard on a broadcast by a very fine saxophone

virtuoso named David Pituch.

David called me up, and just said that he liked my sound.

He liked the fact that it had modern contemporary textures and timbres

and harmonies, yet was accessible and lyrical. For me, that was

quite a compliment because I wasn’t trying to be avant-garde. I

was trying to sing my song, and he was telling me that he heard it, and

that felt very good.

BD: Probably the most important thing is when

you resonate with performers. Then they can then resonate to the

audience. You need that intermediary.

Kritz: That’s right. David said he

would like to meet with me, and consider having me write something for

the saxophone in the same idiom. So we met, and I started out

with a little sketch of an idea, just for a short piece for saxophone.

It ended up being a three-movement concerto for full orchestra and

saxophone! He’s performed it now in several countries including Spain,

Poland, and the United States, with several more performances coming up.

A few other saxophonists have now picked it up and are performing

it in still other countries.

BD: Are you pleased with the way the various

saxophone players have taken it and have interpreted it?

Kritz: It’s an interesting question because

the way I heard it, there were certain jazz idioms in it, certain things

that represented what I was living through when I wrote it and when

I first sketched it. David’s approach to it was a classical approach,

which he was very adept at loosening up into a jazz field, but it was coming

from the classical constructed area, and so it had a totally different sound

than a woman in Poland who picked it up, and plays it from the jazz standpoint,

and tried to impose classical restrictions on the jazz idiom that’s part

of her. It’s looser, it’s less disciplined, but in many ways it’s

also very, very interesting. I can’t say I don’t like it even though

it isn’t exactly the way I wrote it. I still enjoy it.

BD: So, they’re both right?

Kritz: That’s the point! I’m glad you lead

me there, because the performer has as big a stake, and as big a responsibility

as the composer in bringing an art form to fruition.

* * *

* *

BD: Now you’re letting the new ideas flow from

your pen in more and more pieces?

Kritz: Yes. Some of the things I’m doing

are resuscitating old pieces by trying to use the material that has

already been written, and discipline it into the classical structure

that I’ve learned in the last few years. I was taking some classes

in the last couple of years at Northwestern to brush up on some of the skills

in structure and form. So that’s helped me. I have an Octet

that I’m working on, and a Piano Quintet, and songs. I have a

song that I wrote to wonderful poetry which I found when I was twenty-one.

There were some love poems written by my sister when she was sixteen, and

I found them lying around when she was married and out of the house. I

fell in love with these poems, and wrote nine songs.

BD: Do they have a special familial resonance?

Kritz: That’s right. So I wrote these,

and three of them have been performed at least a dozen times by four

different sopranos.

BD: With different performers, you really

get to hear what you have written.

Kritz: Yes, that’s right. I do enjoy

that.

BD: Do you like what you’ve written?

Kritz: The three pieces that I’m really satisfied

with now are the Saxophone Concerto, the Three Songs of

the nine, and the String Quintet. There are some of the other

pieces I feel I can get to where I want them.

BD: You’re in a nearly unique position of having

worked in music, and then gone away from it, and now come back to it.

Is there anything in fifty years in business that has helped or influenced

the music, or are they completely separate?

Kritz: There’s a sense of logic that the business

world imposes on you, and that becomes part of the disciplines that

would impose on your art. You’re looking to sell it, not in the

commercial sense but you’ve learned in the commercial world that whatever

you do has to be perceived that it has a value. In music, that

was an important lesson for me. It wasn’t just to show off a skill,

or to show-off something different, nor was it the opposite, which is just

to speak my own heart, and if the public doesn’t understand it, that’s their

loss. That’s how you feel when you’re twenty, but now I wanted to

take that material, and I wanted you to hear it. I wanted you to sing

with it, and I wanted it to make you feel something, either what I was

feeling, or what it evokes in you.

BD: Should we participate in it?

Kritz: Of course you should, and that’s what

I learned in the commercial world. The tree falling in the forest

does not make a sound. It has to be heard, and I want you to hear

it.

BD: The vibrations mean nothing until they

hit the eardrum?

Kritz: Yes, and in the emotional sense, in

the aesthetic sense, until it communicates to you, it says nothing.

* * *

* *

BD: You used a word that I want to pounce on, and

that’s ‘value’. Can you write value into it, or do you just have

to find that it has value or not once you’ve written the music?

Kritz: It is, it’s a tough word. I

don’t know how to get past that one, because who determines that value?

Is it the number of performances you receive? Is it how many years

from now it will be heard, if any? Is it how deep the impression

is that it makes on one listener, or on many listeners? I can’t

tell you how to judge value, or how I would judge value. I would

settle if I were confident that half a dozen people would hear it in

fifty years. That would represent some measure of value, that I could

say it has some value.

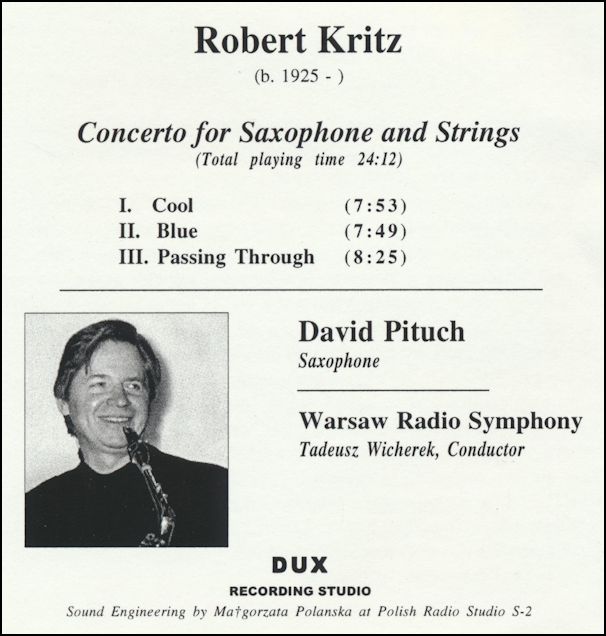

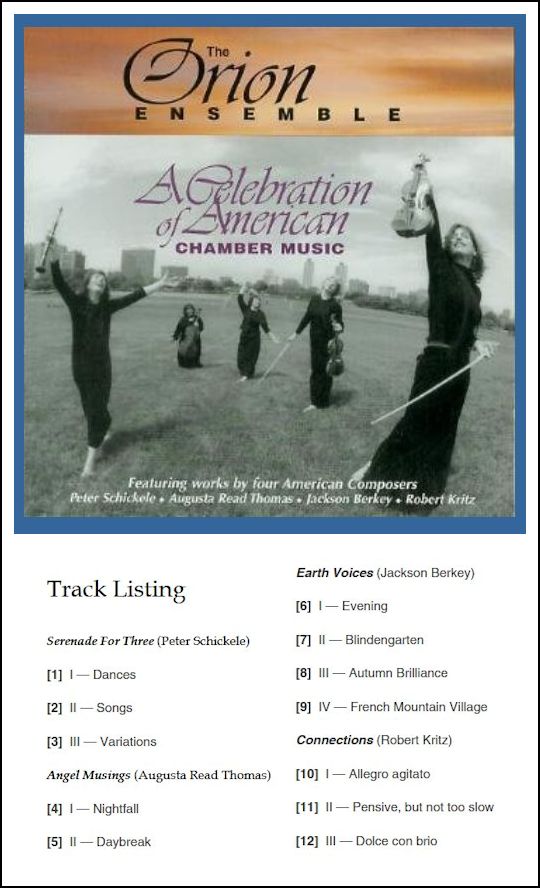

BD: I would assume though that you’d rather

10 million people would hear it? [Vis-à-vis the recording

shown at right, see my interviews with Peter Schickele, and

Augusta Read Thomas.]

Kritz: [Laughs] Of course, I would love that!

But to stick to your question, which is how to measure it in a quantitative

sense, I can’t do that. But in a qualitative sense, if I make contact

with a half-dozen people fifty years from now that hear it, and they

feel something from it, or hear what I’m trying to convey, I won’t say

I’d be satisfied, but that would represent value, and would make everything

I’ve done have some meaning.

BD: Do you have any advice for either young

composers coming along, or men and women in their seventies who want

to either get back composition or even start composition?

Kritz: For young composers, just don’t quit. If

you’ve got it, and you have to say it, and you’re feeling it, you must

let it out. You must not let anything deter you. I know that

sounds like I’m saying I’m sorry for having passed up these fifty years....

BD: [Interjecting] Not really. It

was due to your particular circumstance.

Kritz: Yes, and I don’t feel that fate conspired

against me, or anything like that, because if you have to do it, you’ll

do it. But my advice to the young composer is not to let anything

stop you. If you have to speak, you have to sing. To the older

guys that have felt all these years that they have something to say,

it’s a tough battle because you have to learn the disciplines that add

structure. But do give your voice a chance to be heard in a coherent

manner. Any one of us has got a song to sing.

BD: [Surprised] Really??? You

think everyone has a song?

Kritz: In our hearts, I think everyone has

some agony, or ambition, or regret, or yearning, that he wants to convey.

I’m not saying that it’s necessarily by singing it in the sense

of composing, or in any art form. But we all have some kind of a

yearning that we want to tell someone, or everyone.

BD: That’s the human spirit?

Kritz: Yes. If you want to speak what’s in

your heart, and your language is music, then the job is to find the most

effective meaning, an efficient way of conveying what you are feeling.

If it has good ideas, but is sloppily put together, you’re not going to

get much out of it, except maybe just a nice tune. So what?

BD: Then you’ve wasted the good idea?

Kritz: Yes. It’s the responsibility

of anyone who wants to convey something through an art form to make sure

that it has the best possible chance of connecting.

BD: Let me ask a balance question. Either in

your music, or music in general, how much is art, and how much is entertainment?

Kritz: That’s a good question following what we were

just talking about. Is it entertainment to connect to make somebody

want to sing your song? By that I don’t just mean to whistle the

tune that you presented. I mean to sing your song and say what

this guy is trying to tell me.

BD: To feel your feelings?

Kritz: Yes, feel. Entertainment has to

be the device, the vehicle, to carry your feeling, but the goal has

to stay the same. You’ve got something, and you want to convey it

honestly. If you want to write a song, and you have the gift of

being able to write a song, you should write a song. When I’m trying

to say something, to sing something more than a song, I don’t know if I’ve

succeeded. But I’ve tried to do all I can in developing the skills

necessary for that song to at least have the chance to get to you. Then

it’s up to you to tell me whether you feel that I’ve been successful.

* * *

* *

BD: I asked you before if you had helped to get some

of the businesspeople back into music. Now that you’re away from

business, are you conscious of those businesspeople that you’ve left

behind, and are you trying to touch them perhaps more especially than

other musicians?

Kritz: I can’t say that I have. No, I can’t

say I’ve made any effort. I’ve tried to get them to come to a concert

that looks good and that looks like it would be pleasing, and I have tried

to introduce people that weren’t exposed to serious music.

BD: I’m trying to make a connection,

because you’re one of the few who has successfully gone into both camps.

Usually, musicians aren’t particularly successful in business, and most

businesspeople are not particularly successful musicians.

Kritz: I don’t think that you could say I was successful

in business in the sense of working for a large company with affluent

results. In a manner of speaking, I was able to support myself in

the business field while maintaining an interest in a form of art.

BD: I’m glad you maintained that love of

music throughout.

Kritz: Oh yes, I had to. Every three

or four years, I’d pull out this Quintet that had had several

performances fifty years ago, and I would just go through it. Sometimes

I would try to transcribe it for piano so I could hear some of those

harmonies again. I was always trying to find out if this thing

worked. Does it speak? Does it sing for me? But every

time I would get into it, after five or six hours of trying to transcribe

it I’d end up having to get back to business. Finally, at age sixty-nine,

I went for it. I mentioned earlier Dr. Richard Green, and David Pituch.

Then, a year ago, at a performance of the Do-It-Yourself Messiah,

I met the conductor Susan Davenny-Wyner, and her husband, the eminent composer

from Brandeis University, Yehudi Wyner. They

were at the reception afterwards to which I was invited, and I was introduced

to Yehudi Wyner as a re-emerging composer. He showed some kind

of interest, although I didn’t know why because he’d never heard of me.

But he was just a nice guy, and he said to send him some tapes. So

I thanked him for being willing to listen, and he said, “Don’t

thank me yet. I may end up telling you that they’re no good!”

[Both laugh] He wrote a few weeks later with some very encouraging

and glowing remarks that gave me great encouragement to continue at a

time when I was deciding to go one way or the other. He sustained

my faith in the fact that I did have a song to sing, and that he wanted

me to keep singing it.

BD: Now, you’re back into music completely?

Kritz: Now I’m back completely into it.

BD: Do you have any regrets?

Kritz: None, no! I’m fine with it,

and I’m so glad that you’ve offered to play some of my music on WNIB.

BD: Now that you’re back into it full-time, is composing

fun?

Kritz: Yes. It’s a way of getting lost in trying

to find who you are and what you have to convey. That’s the real

pleasure, the real joy of doing it. The satisfaction is you understanding

what I’m talking about or singing about, and maybe gaining something

from you... perhaps an insight or two! [Both laugh] But the

joy of doing it is indescribable, even getting lost and reworking one measure

for three hours.

BD: Are you ever finished?

Kritz: [Laughs] That’s a good question,

because, in the case of the first three pieces that have been performed

so often recently, I’ve made revision after revision.

BD: I would think that would drive your publisher

nuts! [Both laugh]

Kritz: I suppose if I had studied all through these

fifty years, and stayed in the business

— not the business of selling

the music, but the business of constructing it with form and coherence

— I’d be more

fluent in the language, and I wouldn’t have to work so hard at finding

every single thing I’m trying to convey. But now, since I’m working

at this, I’ve had to search for everything. I talked about this briefly

with Yehudi just last week, and he says it never stops. [Laughter]

But I’m satisfied now that the Quintet will stand or fall just

the way it is. As to the Three Songs that have received all

these performances recently, I’m satisfied with the original version,

which is with string accompaniment. I’m not satisfied with my piano

transcription, nor am I satisfied with the piano transcription of the

Saxophone Concerto. After David had performed it with several

orchestras, he asked me to do what they call a reduction for saxophone

with piano, so it could be a recital piece as well as a concert piece.

But I’m not satisfied with the job I did on that.

BD: Is this because it’s a distortion of

the original?

Kritz: That’s true, but it can still be better, and

it is going to be better because that’s all I’ve been doing for the

past month.

BD: Should you spend your time fixing that

up, or should you spend your time writing new pieces and getting a few

more songs out?

Kritz: That’s a hard choice. I am working on

one piece right now at the same time as the revisions. Dr. Fred Hemke, the assistant

Dean at Northwestern Music School, is also a saxophonist, and he heard

the other saxophone piece that I wrote for David, and has commissioned

me to write a piece for him for a new CD that he’s going to do.

He asked me for a six-minute intermezzo, and I’m working on that, and

that’s great fun. So, you’re right! The supreme joy is the

new composing. But working on revising, and refining, and getting

it exactly where you want it is joy, too. It’s not tedium.

It’s fruitful and it’s rewarding.

BD: Thank you for coming back to the music.

Kritz: I’ve enjoyed so much talking to you.

===== =====

=====

--- --- ---

===== =====

=====

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 17, 1998.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following November, and again

in 2000. This transcription

was made in 2025, and posted

on this website at that time.

My thanks to British

soprano Una

Barry for her help in preparing

this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here.

To read my thoughts

on editing these interviews for print, as

well as a few other interesting observations,

click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce

Duffie was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until its

final moment as a classical station

in February of 2001. His interviews

have also appeared in various magazines

and journals since 1980, and he now continues

his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more

information about

his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also

like to call your attention to the

photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive

field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and

suggestions.