|

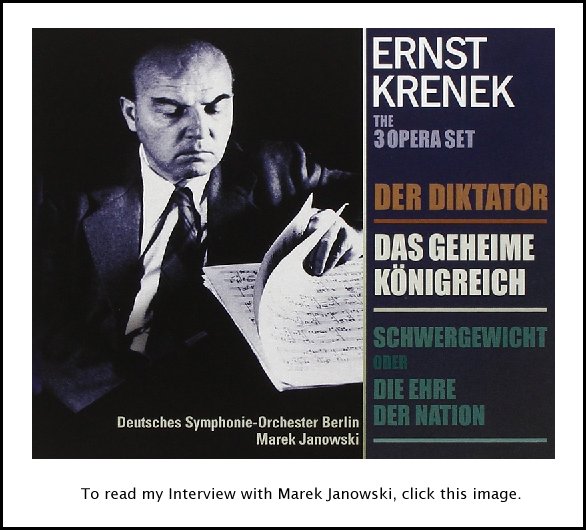

Ernst Krenek

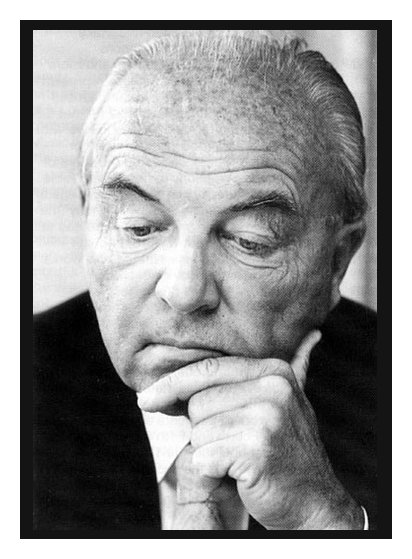

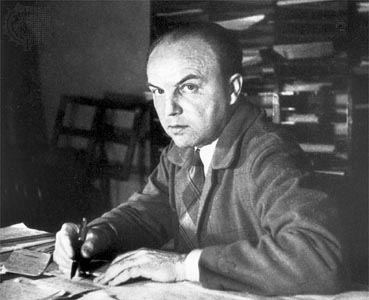

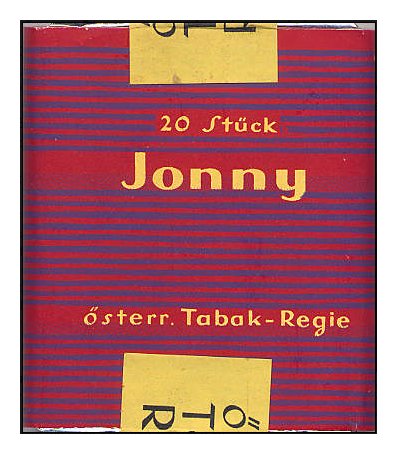

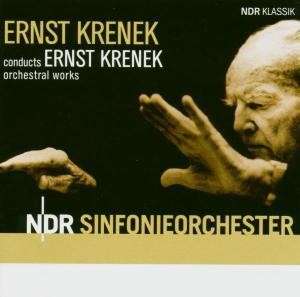

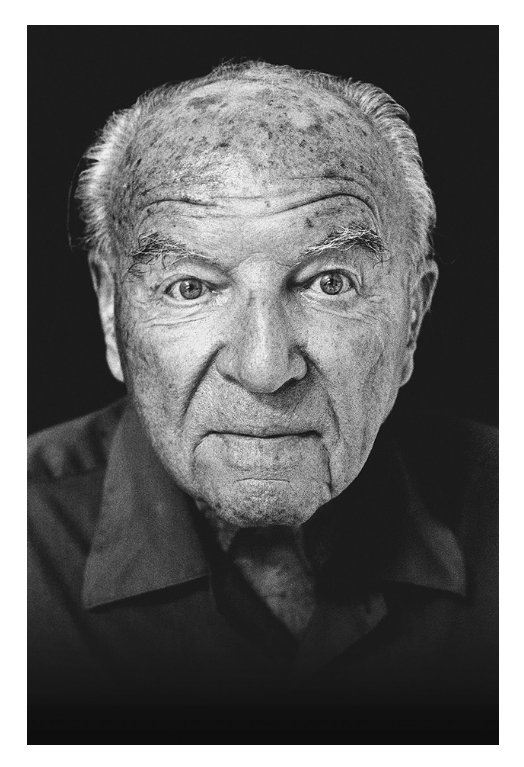

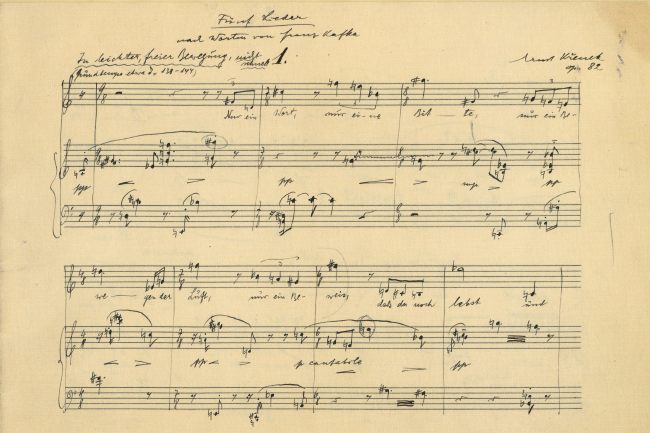

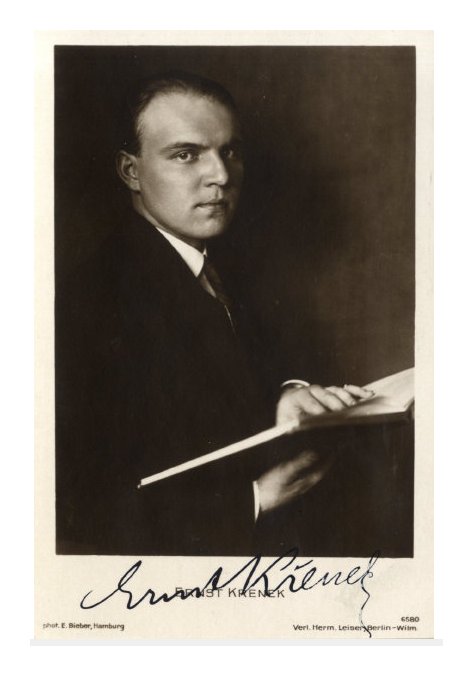

Ernst Krenek (August 23, 1900 – December 22, 1991) was an Austrian-born composer of Czech ancestry; throughout his life he insisted that his name be written Krenek rather than Křenek, and that it should be pronounced as a German word. He explored atonality and other modern styles and wrote a number of books, including Music Here and Now (1939), a study of Johannes Ockeghem (1953), and Horizons Circled: Reflections on my Music (1974). Krenek was born in Vienna. He studied there and in Berlin with Franz Schreker before working in a number of German opera houses as conductor. During World War I, Krenek was drafted into the Austrian Army, but he was stationed in Vienna, allowing him to go on with his musical studies. In 1922 he met Gustav Mahler's daughter, Anna, and her mother, Alma, who asked Krenek to complete her late husband's Symphony No. 10. Krenek helped edit the first and third movements but went no further. In 1924 he married Anna, only to divorce her before the first anniversary. His journalism was banned and his music was targeted in Germany by the Nazi Party in 1933. On March 6, one day after the Nazis gained control of the Reichstag, Krenek's incidental music to Goethe's Triumph der Empsindsamkeit had to be withdrawn in Mannheim and pressure was brought to bear on the Vienna State Opera, which cancelled the commissioned premiere of Karl V. The jazz imitations of Jonny spielt auf were included in the 1938 Degenerate art exhibition in Munich. He moved to the United States of America in 1938 where he taught music at various universities, including Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota from 1942-1947. He became an American citizen in 1945. His students included George Perle and Robert Erickson. [See Bruce Duffie's Interview with George Perle, and his Interview with Robert Erickson.] Krenek died in Palm Springs, California. Krenek's music is in a variety of styles. His early work is in a late-Romantic idiom, showing the influence of his teacher Franz Schreker. He later embraced atonality, but a visit to Paris, during which he became familiar with the work of Igor Stravinsky and Les Six, led him to adopt a neo-classical style. His opera Jonny spielt auf (Johnny Strikes Up, 1926), which is influenced by jazz, was a great success in his lifetime, playing all over Europe. In spite of Nazi protests, it became so popular that even a brand of cigarettes, still on the market today in Austria, was named "Jonny". [Illustration of a pack is shown in the box below.] He then started writing in a neo-Romantic style with Franz Schubert as a model, with his Reisebuch aus den österreichischen Alpen as prime example, before using Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique; the opera Karl V (1931-33) is entirely written using this technique, as are most of his later pieces. In the Lamentatio Jeremiae prophetae (1941–42) he combined twelve-tone writing with 16th century techniques of modal counterpoint. He also composed electronic and aleatoric music. |

BD: But of course this is a conscious choice on your

part.

BD: But of course this is a conscious choice on your

part.On Dec. 6., 2011 Decca Classics' latest

slate of back-catalogue opera reissues includes the important Leipzig

recording of Ernst Krenek's jazz opera Jonny

spielt auf. An Austrian of Czech descent, Krenek (1900-1991) was no jazzman. He was in

fact a fiercely eclectic, modern composer whose music veered from tonality

to serialism and sometimes back again in the course of a long, brilliant

career. Today, he is best remembered as a music educator and for making the

first attempt to edit the score of Mahler's Tenth Symphony. He is also an important,

underrated composer in the 20th century whose cerebral music deserves more

exposure.

An Austrian of Czech descent, Krenek (1900-1991) was no jazzman. He was in

fact a fiercely eclectic, modern composer whose music veered from tonality

to serialism and sometimes back again in the course of a long, brilliant

career. Today, he is best remembered as a music educator and for making the

first attempt to edit the score of Mahler's Tenth Symphony. He is also an important,

underrated composer in the 20th century whose cerebral music deserves more

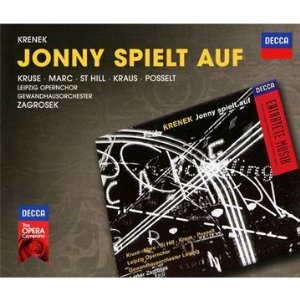

exposure.Jonny (the title translates as Jonny Plays On) was the hot opera of 1928. Krenek was inspired by the jazz revue Chocolate Babies. The opera premiered in Leipzig in 1927 and was an instant success. It is the story of a love affair between Max, an intellectual composer (Krenek himself?) and Anita, a soprano. The title character, an itinerant African-American musician (usually played by a white actor in black-face) sets the world dancing after he steals Max's violin. When Jonny-mania hit Vienna, Krenek's innovations drew the ire of that city's leading music critic, one Julius Korngold. The father of composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold, the elder Korngold worked hard to promote the virtues of his son's more conservative (but equally brilliant) opera, Das Wunder der Heliane. But he did so by writing negatively about Krenek's opera. The effort backfired, and Heliane fizzled.  The competition between operas extended as far as the smoke shops of the

Austrian capital. Ostereiche Tabakregie

promoted the elegant, expensive "Heliane" cigarettes as an alternate to the

cheap "Jonny" blend. Like Krenek's opera, the plebian taste proved more popular.

(You can still buy Jonny cigarettes in Austria. [See illustration at left.]

In interest of public health, this blog does not recommend you do so.)

The competition between operas extended as far as the smoke shops of the

Austrian capital. Ostereiche Tabakregie

promoted the elegant, expensive "Heliane" cigarettes as an alternate to the

cheap "Jonny" blend. Like Krenek's opera, the plebian taste proved more popular.

(You can still buy Jonny cigarettes in Austria. [See illustration at left.]

In interest of public health, this blog does not recommend you do so.)The rise of Adolf Hitler led to both operas being labeled "Entarte Musik," examples of what Nazi censors called "degenerate" art, and then banned. Jonny languished in obscurity for the next 50 years. Although it never regained a place in the repertory, it is staged occasionally, with productions in Vienna (2005) and at the Teatro Colon in Argentina in 2006. Both composers emigrated to America. Krenek became an academic and wrote an important Violin Concerto. Korngold went to Hollywood and found fame writing film scores. The recording in question comes from the 1990s, when Decca started a program to record and preserve these specific operas that were declared "degenerate." Both Jonny and Heliane were recorded as part of that series. The jazz opera was preserved on this excellent two-CD set, featuring the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra conducted by Lothar Zagrosek. The cast features heldentenor Heinz Kruse as Max, and soprano Allessandra Marc as Anita. Thanks to this reissue, you can discover Jonny for yourself. -- From a blog called "Superconductor"

by Paul Pelkonen (with correction)

|

BD: Where is the balance?

BD: Where is the balance? EK: Yes. I was

asked by the Italian Radio to write a piece for the 200th anniversary of

Bach's death, which was in1750. I came to this idea to write a piece

which is all dressed up in a sense that it is a kind of compressed picture

of my idea of the development of music history since Bach. I start

with this theme of B-A-C-H, and I find it again in the last four string quartets

by Beethoven, and suddenly in Tristan

by Wagner and eventually in our new 12-tone music. This is exemplified

in this piece. It's a string trio, and I had to write a preface, so

what should I do? I don't speak enough Italian; they don't know English,

and they don't know German, so I wrote it in Latin. I wrote a Latin

preface which I still remembered from my high school days. It was very

well done when they played this piece, but it was printed only in the publication

called Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach

Institute, and nowhere else. I was astonished to see it being

performed here and there, so it gets around without my knowing.

EK: Yes. I was

asked by the Italian Radio to write a piece for the 200th anniversary of

Bach's death, which was in1750. I came to this idea to write a piece

which is all dressed up in a sense that it is a kind of compressed picture

of my idea of the development of music history since Bach. I start

with this theme of B-A-C-H, and I find it again in the last four string quartets

by Beethoven, and suddenly in Tristan

by Wagner and eventually in our new 12-tone music. This is exemplified

in this piece. It's a string trio, and I had to write a preface, so

what should I do? I don't speak enough Italian; they don't know English,

and they don't know German, so I wrote it in Latin. I wrote a Latin

preface which I still remembered from my high school days. It was very

well done when they played this piece, but it was printed only in the publication

called Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach

Institute, and nowhere else. I was astonished to see it being

performed here and there, so it gets around without my knowing. EK: Opera should be a theater piece. That's

the main thing; it's a dramatic piece to be put on stage, and it is permeated

by music. The music comes from the orchestra, which is below, but the

first thing is that it's a dramatic piece. The subject matter and the

dramatic treatment is of utmost importance. That is a mistake which

I have noticed frequently. Students of mine would rave about a fiction

book they have read. They would say, "This is a wonderful opera libretto

and I don't know what I want to do with this." But they forget that

it's not dramatic. It has too many descriptions and not enough facilities

for dialogue since they're simply not dramatic situations. It doesn't

lend itself to dramatic treatment. The drama is the first thing you

feel with all great operas.

EK: Opera should be a theater piece. That's

the main thing; it's a dramatic piece to be put on stage, and it is permeated

by music. The music comes from the orchestra, which is below, but the

first thing is that it's a dramatic piece. The subject matter and the

dramatic treatment is of utmost importance. That is a mistake which

I have noticed frequently. Students of mine would rave about a fiction

book they have read. They would say, "This is a wonderful opera libretto

and I don't know what I want to do with this." But they forget that

it's not dramatic. It has too many descriptions and not enough facilities

for dialogue since they're simply not dramatic situations. It doesn't

lend itself to dramatic treatment. The drama is the first thing you

feel with all great operas. EK: Yes. I wrote two operas and one short play

for television. I liked to do that very much, especially the first

opera that was written for the Austrian Television. It was a superior

production, really excellent. There was a television stage director

who really understood his job, and he understood what I wanted. He

created an excellent production, but unfortunately he has died. But

it was interesting because they said they wanted a live production with video

and audio at the same time. That was a rather difficult job because

I was conducting the orchestra in the radio building in the broadcasting

station, and the singers were singing and acting out their parts about six

miles away in Castle Schönbrunn. I had a camera on myself so that

they could see my conducting, but actually actors or singers cannot watch

from a screen, so they had two auxiliary conductors jumping around between

the cameras and taking my beat from the screen and passing it on to the singers.

Those extra conductors also had to be watching so that they wouldn't get

in the field of vision of the camera. So that was something.

EK: Yes. I wrote two operas and one short play

for television. I liked to do that very much, especially the first

opera that was written for the Austrian Television. It was a superior

production, really excellent. There was a television stage director

who really understood his job, and he understood what I wanted. He

created an excellent production, but unfortunately he has died. But

it was interesting because they said they wanted a live production with video

and audio at the same time. That was a rather difficult job because

I was conducting the orchestra in the radio building in the broadcasting

station, and the singers were singing and acting out their parts about six

miles away in Castle Schönbrunn. I had a camera on myself so that

they could see my conducting, but actually actors or singers cannot watch

from a screen, so they had two auxiliary conductors jumping around between

the cameras and taking my beat from the screen and passing it on to the singers.

Those extra conductors also had to be watching so that they wouldn't get

in the field of vision of the camera. So that was something. BD: Are you a good audience for standard works

— Beethoven symphonies, Mozart operas, things like that?

BD: Are you a good audience for standard works

— Beethoven symphonies, Mozart operas, things like that? BD: Is the public always right in its taste, dictating

who will be played and who will not be played?

BD: Is the public always right in its taste, dictating

who will be played and who will not be played? EK: The chamber operas were mainly written for special

occasions. There was either a commission or a small beautiful studio,

or television with a small orchestra or small ensemble. It depends

a little on these things. Most of the full-sized operas were commissioned

by opera houses. So it depends on the occasion how such things originate.

In the early days when I was not yet so established, I had no commissions.

I just had the idea for Jonny spielt auf

and I did it, I wrote it on my own. I was tempted to use the terrific

machinery of the theater. At that time I was employed by the opera

house in Kassel for ten years, and I learned about all this machinery and

gadgets which you can use. It was a challenge to write an opera where

all these techniques should be to put into action. We couldn't have

done Jonny spielt auf without a

lot of that equipment.

EK: The chamber operas were mainly written for special

occasions. There was either a commission or a small beautiful studio,

or television with a small orchestra or small ensemble. It depends

a little on these things. Most of the full-sized operas were commissioned

by opera houses. So it depends on the occasion how such things originate.

In the early days when I was not yet so established, I had no commissions.

I just had the idea for Jonny spielt auf

and I did it, I wrote it on my own. I was tempted to use the terrific

machinery of the theater. At that time I was employed by the opera

house in Kassel for ten years, and I learned about all this machinery and

gadgets which you can use. It was a challenge to write an opera where

all these techniques should be to put into action. We couldn't have

done Jonny spielt auf without a

lot of that equipment.

This interview was recorded on the telephone on January 18, 1986. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1990, 1995, and 2000. A copy of the unedited audio was given to Yale University, as part of their Oral History American Music archive. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.