Conversation Piece:

Manager ARDIS KRAINIK

By Bruce Duffie

Conversation Piece:

Manager ARDIS KRAINIK

By Bruce Duffie

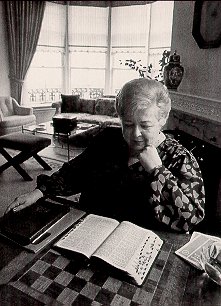

Lyric Opera of Chicago is one of the great companies of the world, and to a large measure, the reason for its success in recent years is due to the General Director, Ardis Krainik. Under her skillful hand and watchful eye, the impossible task of presenting first-rate opera for many weeks each season becomes seemingly effortless. The case, however, belies a tremendous amount of hard work, diligence and sheer fortitude to manage the myriad aspects that must be brought together each evening.

A singer herself in the early days of the company, Krainik found herself drawn more to the administration offices, and worked her way up through the ranks to become assistant to Carol Fox, one of the founders of Lyric in 1954. Having been so close to everything and everyone, when Ms. Fox retired, the board of directors immediately and decisively engaged Ardis Krainik to become the General Director.

Resident opera came to Chicago back in 1910, but changing circumstances forced companies to fold and be re-formed under different auspices. Lyric Opera of Chicago, the longest company in the city's history, opens its Gala 35th season this fall in a blaze of artistic glory and a healthy financial situation, thanks mostly to the care and guidance of Ardis Krainik. Truly the right person for the job in the 1980s and ‘90s, the Windy City is lucky that she gives the company her time, effort and love.

Always bright and effervescent, it is obvious to anyone who meets

her that Ardis Krainik does this difficult and strenuous job

superbly.

Having admired her work for so long, and speaking with her briefly on

many

occasions, it was a special pleasure for me to sit down one afternoon

with

this human dynamo for an in-depth chat about our mutual passion.

Here is much of what transpired between us in her office last year . .

. . .

Bruce Duffie: (somewhat mischievously) Let's start out with a real easy question - where is opera going today?

Ardis Krainik: (with a big smile) Oh, that's the worst question you could possibly ask! I can't tell you the answer. I can make a lot of guesses. My main guess is that it's going up and onward. Wonderful things are happening in opera. There are some problems, too, but there's never been a time when there haven't been problems. I think American opera is really taking hold in a most wonderful sort of way. We have lots of new works; we have new stage directors and designers who are coming into great prominence; we have American conductors who are beginning to be recognized internationally; and the American singing artist has practically taken over the world! [Note: At this point, she lists many singers, all Americans, all of international renown, all of whom appear on recordings . . .] People are coming to opera, enjoying opera. All the companies except the Met are using ‘surtitles' which makes it much more enjoyable. Audiences enjoy the whole experience much more, and that translates into people buying tickets at the box office. And as long as people buy tickets at the box office, opera is on its way up.

BD: You as the General Director must balance the artistic considerations with financial decisions. Is this a delicate juggling act?

AK: Yes, but I think it's fun. I make decisions based on what I see on paper. The artistic decisions are made looking at figures because I see how one thing balances against another dollar-wise. I can make an opinion of what I should do artistically based on that. If the dollar-figure is too much, we must reluctantly not attempt the project. Sometimes, however, when one idea is impossible, another presents itself, and that new idea is often even better while coming in with something I can afford. It's a jigsaw - fitting all the little pieces together. You can't talk about one without the other.

BD: Do the pieces always fit together?

AK:

You can always find something that is not a compromise, but is another

avenue which gives you the same artistic cachet. In this world

there

are many artistic expressions. One may cost a million dollars,

another

only half that much, but they're both valid. Hopefully I'm a good

enough manager that I can find the best value without compromising

standards.

I have a lot of help in doing that with my Artistic Director, Bruno

Bartoletti,

and Danny Newman who knows so much about what sells and how to promote

opera, Bill Mason, the Director of Operations which is really Artistic

Administrator, and Matthew Epstein my Artistic Consultant. So I

have

a lot of help. [Note: William

Mason (who sang the Shepherd Boy in Tosca during the first few seasons!) would

succeed Krainik as General Director of the company in 1997 and hold the

post until he retired in 2011. Also, see my Interview with

Danny Newman.]

AK:

You can always find something that is not a compromise, but is another

avenue which gives you the same artistic cachet. In this world

there

are many artistic expressions. One may cost a million dollars,

another

only half that much, but they're both valid. Hopefully I'm a good

enough manager that I can find the best value without compromising

standards.

I have a lot of help in doing that with my Artistic Director, Bruno

Bartoletti,

and Danny Newman who knows so much about what sells and how to promote

opera, Bill Mason, the Director of Operations which is really Artistic

Administrator, and Matthew Epstein my Artistic Consultant. So I

have

a lot of help. [Note: William

Mason (who sang the Shepherd Boy in Tosca during the first few seasons!) would

succeed Krainik as General Director of the company in 1997 and hold the

post until he retired in 2011. Also, see my Interview with

Danny Newman.]

BD: Ever get too much help?

AK: You can never have too many ideas - the problem is choosing the right one.

BD: If you had a blank check and could run 52 weeks instead of 20, what would you do differently?

AK: I don't think you can do opera 52 weeks a year. Even the Met, which pays on that basis, doesn't perform every week of the year. An opera house is not a factory. Great art doesn't run on a 52 week cycle. I'm not against full-time employment, but I don't believe you can crank out one opera after the other without everybody getting terribly tired and blasé. Here, we have the same pool of musicians in the pit for every opera, and each production has the exact same players for the entire run. The sense of ensemble and playing together in a musical entity from having rehearsed together is very important.

BD: This is one of the components. What else constitutes great art in the opera house?

AK: To me, great art in opera starts with the voice, the singer. If you don't have wonderful singers, you're not going to get great art. People will disagree with me, but I stand my ground. Without the singers there is no opera. You also have to have a great orchestra and great conductor, and nowadays where there is so much attention paid to what you see, you must have great stage direction and great scenic designs. The audience must know that you're up-to-date. If Lyric Opera of Chicago put on opera in the sets from 50 or 60 years ago, or even the sets from the time when Callas made her American debut here, people would laugh us off the stage. The wonderful memories we have of her and Tebaldi and all the other greats are nostalgic and beautiful, but to see those sets today would be absolutely nothing. Those singers, by the way, brought their own costumes! No sets and costumes were fashioned together, so there was no cohesive artistic whole in what you looked at. It was a hodge-podge and you were glad it was in some kind of artistic setting. Nowadays, people expect so much more. We have to compete with television, and we rely on what people see as well as what they hear. People want to come to a great show, and when they get great singing and dancing and a great orchestra with great scenery and costumes, they really come away with all of it. So you can't give them any less anymore.

BD: Well then, where is this delicate balance between art and entertainment?

AK: I don't want to go to a great piece of art that isn't entertaining. Mozart wrote operas that he wanted people to love and go to. When someone says you can't call opera ‘entertainment,' I say, "Why not?"

BD: Aren't the so-called ‘serious' operas of Mozart, such as Idomeneo or Clemenza di Tito different?

AK: No, he wrote a different kind of entertainment. His genius found other ways to express itself, but it was still done for an audience. I'm not saying opera is not art. I think opera is the highest form of entertainment that there is in the world. It's better than anything else. It combines every aspect of any art form that there is. Everything is in opera, and therefore it is great art, but it is also at the same time entertaining. Even Wagner built his theater in Bayreuth so that people would come! Don't misunderstand - I don't think these pieces aren't great art, but neither do I want people scared away thinking they can't come and enjoy.

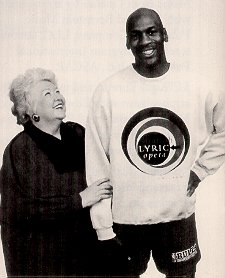

BD: Is opera for everyone?

AK:

You bet it is! You bet it is! Why not? Why should we leave

anybody out of anything that is so wonderful? In Italy, in the

time

of Verdi and Puccini, even the lowliest laborer went around singing the

tunes. Why shouldn't we have that now? I think it's wonderful

music,

so why shouldn't everyone enjoy it? I'm a very great populist on

this. I don't want to lower the art form in any way. No one

in my position should ever think of presenting opera on anything but

its

highest level. I don't want to democratize things to the point

you

don't have true art any more. But everyone can understand the

very

highest level of art. Opera is so wonderful because the depths

are

so unfathomable. It's impossible to plumb your way down to the

last

thing. There's an ever-widening circle; the more you learn about

it, the more there is to learn.

AK:

You bet it is! You bet it is! Why not? Why should we leave

anybody out of anything that is so wonderful? In Italy, in the

time

of Verdi and Puccini, even the lowliest laborer went around singing the

tunes. Why shouldn't we have that now? I think it's wonderful

music,

so why shouldn't everyone enjoy it? I'm a very great populist on

this. I don't want to lower the art form in any way. No one

in my position should ever think of presenting opera on anything but

its

highest level. I don't want to democratize things to the point

you

don't have true art any more. But everyone can understand the

very

highest level of art. Opera is so wonderful because the depths

are

so unfathomable. It's impossible to plumb your way down to the

last

thing. There's an ever-widening circle; the more you learn about

it, the more there is to learn.

BD: Are we blurring the lines between opera and musical comedy?

AK: Today the lines are becoming blurred with pieces like Les Miserables and Phantom of the Opera. I don't think it matters. If I wanted to put one of those on here at Lyric, I'd call up Hal Prince and find out if it was workable. [See my Interview with Hal Prince.] But most of the producers of those works see their commercial value not in the opera house but where it's more economically feasible, and there's nothing wrong with that. I'm not considering any of these works right now, but I don't cross it off the list. If I run into evil financial days, I'd turn to something like that rather than close down. A lot of companies around America are doing musicals in their seasons. It adds an extra dimension and brings in audiences. Maybe if they come to My Fair Lady, they'll try Bohème and if they like the Puccini, maybe they'll try Verdi and even Wagner! I know that the minimalists have made a transition in opera from the early 20th Century to the late 20th Century. We have a different kind of opera being written now, perhaps because of Philip Glass. [See my Interviews with Philip Glass.] It doesn't mean we're changing our direction, it means we're adding on. I don't want to get rid of Carmen and Tosca, but we are adding on something new to our pleasure and enjoyment.

BD: Can the use of surtitles make stage-direction more subtle?

AK: I hope not. Opera is theater and in order to get an idea across you've got to see a nuance in the face, see the arm move, or whatever. It can't be any less because the titles are above. Besides, you can't disappoint those who only want to listen and look at the stage. You have to be every bit as dramatic as you ever were - maybe more rather than less.

BD: Do you feel stage directors do too much, or go too far?

AK: Yes. I've seen performances in other theaters where there was so much going on onstage and so many distractions that the most beautiful singing was lost. The director, as far as I'm concerned, must be absolutely faithful to the text and let the singer have the spotlight rather than the mechanics. The beautiful song, which is what opera is all about, must get the most focus. But what is ‘too much' or going ‘too far?' That is very subjective.

BD:

I assume you have veto power with productions here at Lyric.

BD:

I assume you have veto power with productions here at Lyric.

AK: Yes I do, but I don't think I've had to exercise that power. I hire the great people, and those are the ones you have to pay the least attention to. They are great in their field and they know how to do it. The concept is discussed when there are new set-designs, but you don't talk about what they will do precisely on the stage. I see the ideas on the stage during rehearsal and if necessary we talk about it. I don't actually veto, we discuss it if I really don't like something. But those instances have been very, very few.

* * * * *

BD: You have a choice of hundreds of operas to present. How do you make your selections, and are there any you're dying to put on but haven't gotten around to as yet?

AK: I don't have any big desires because we always put on what I want to put on. What I want to do is commission a composer to write an opera for us. [Note: It has recently been announced that William Bolcom has agreed to do a major work for Lyric Opera, to be staged a couple of seasons hence.] I want to do new works that are important, works that people will love and come to. That is more important than any single opera of the past that I may want to do that we haven't done. But in planning, you try to make a balance, not just season by season, but over three seasons. The old chestnuts must be represented fully, as well as the esoteric and the new operas. Besides the Italian, you need French and German, etc. You can't leave anything out of the panorama. Then, within that frame, your choice depends on what singers you get and what you want them to do. You don't want to do Masked Ball too many times, and you can't do Wozzeck more than a certain number of times. Our Lulu was so outstanding and well-received that it will long live in peoples' memory, but I'm not sure they would buy tickets again very soon. If we do a sensational Traviata, people will return not because it's sensational, but because they want to see Traviata again. Some works that are successful I'd like to repeat in three or four years, but not any sooner. I've learned how to sell things and market them here in Chicago. In New York, where there are simply more performances and more people, things can come back sooner and more often. You need a balance, but the starting point and focus is to put on the greatest possible opera that you can for this city.

BD: Is the public in Chicago significantly different from that in New York or San Francisco, or in Europe?

AK: Our audiences are very discerning. We don't seem to applaud as long as in other cities, but the appreciation is there and knowledge and understanding is apparent. The artists can feel it on the stage during the performance as well as during the curtain calls. What really tells you if the audience likes what you're doing is whether they buy tickets or not, and we're always sold out. I wouldn't trade our audience for that of any other city in the world.

* * * * *

BD: What advice do you have for young singers coming along?

AK: The young singer today really has it made. When I was coming along, there were hardly any opera companies, and no company had a program where the young singer could prepare for a career by living in the company. Besides our Lyric Opera Center for American Artists, there are similar programs in several of the major companies. So my advice is to get into one of these programs. That way they can be part of the living, breathing, daily fabric of the company. First, of course, they need to get a good teacher to learn the mechanics, but the polish comes from an apprentice program with a company.

BD: Any advice for young conductors?

AK: In most businesses, you have to start at the bottom, and that's true of opera as well. Singers don't step onstage in leading roles, but in shorter, supporting ones. The most useful conductor for the opera and for the company is one who knows the works and understands singers the best. Being a coach, which is how most of the great conductors began, is still the way. It isn't the youngster who decides where he will go; you must go where you can get a job. We have a couple here with Lyric who have come up the route in opera by being coaches and rehearsal pianists. You can study an opera all you want, but you really learn it by playing it and working with the singers. Even going in front of the orchestra without singers won't do it. There are certain special things that a great opera conductor has, and the most important is the understanding of how the human voice breathes and does its best. A great conductor listens to the singers and makes it possible for them to be their very best in every place. You don't have to be a great symphonic conductor to be a great operatic conductor.

BD: What about the budding young stage director?

AK: That's the toughest spot of all because there are a lot more stage directors than there are jobs. Some people have the idea that they have to be unique or so bizarre and do something different, and they're not true to the text or the tradition. They want to do something way out and they drift off into directions that may or may not work. A few lucky youngsters become apprentices to great directors, and sometimes become great in their own rights. It's like the old way of becoming an apprentice to a cobbler as a way of learning to make shoes, and eventually you become a master of the craft, and a master singer to boot! (Laughter)

BD: OK, now the toughest question of all - how does one learn to run a great opera company?

AK:

Same way. When I became General Director, there was very little

about

an opera company that I didn't know. I'd been here for 27 years -

the longest apprenticeship in history! Perhaps you become an

assistant

in the rehearsal department, or a typist, or an assistant to somebody

somewhere

along the line, and work your way up. It works that way in

business,

and opera functions in much the same way. I suppose you could

start

your own company and learn by being General Director of it, but you'd

still

have the learning experience to go through. I consider myself

lucky

indeed to have attached myself to one of the great opera companies of

the

world and learned how to do things by following the advice of people

who

knew what they were doing.

AK:

Same way. When I became General Director, there was very little

about

an opera company that I didn't know. I'd been here for 27 years -

the longest apprenticeship in history! Perhaps you become an

assistant

in the rehearsal department, or a typist, or an assistant to somebody

somewhere

along the line, and work your way up. It works that way in

business,

and opera functions in much the same way. I suppose you could

start

your own company and learn by being General Director of it, but you'd

still

have the learning experience to go through. I consider myself

lucky

indeed to have attached myself to one of the great opera companies of

the

world and learned how to do things by following the advice of people

who

knew what they were doing.

BD: Are there still things that hold terrors for you in this job?

AK: Everything holds terrors for me in this job. The more important this company becomes, the more fame we attain as an opera company, the greater works that we put on, the closer you are to the top, the harder it is to stay there, and that has its own terrors. I pray a lot. I consider that a very important component to being General Director. There are times when only that will get you out of a spot. You pray sincerely and listen carefully for that still small voice that says, "This is the way; walk ye in it." In the old days, when Carol Fox ran the company, she forged it out of rock. There was nothing there and she made it. That was not the time when you paid attention to budgets. It was a swashbuckling time where you said, "This is what we're going to do" and you went out and raised the money. It was a very successful operation, but now times have changed. The things we could do 20 years ago are too costly to do on the same level today. The highest level then is infinitely more costly today than the inflation has been. And our world has become much more sophisticated. There were no computers then and travel was much more simple and more graceful than it is now. In the old days, artists would come and spend the whole season or half the season with you. For example, Covent Garden and Munich didn't run international seasons; they had a company that stayed with them, and they might bring in "the Italians" for a month. The knowledge of what your colleagues were doing was not so important. Because we can't afford to do so many things now, we all want to be collaborative. When opera administrators get together, we talk all the time about doing things together. And, of course, every one of us is using the same people.

BD: Are we over-using those same people?

AK: What does it matter? They're the great singers

and

you try to get ‘em. If you're an international opera company, you

really don't have any choice. You try to develop new ones and

bring

them along, but then they become the same big, international

singer.

We treat our artists with consideration and love. That's the

operative

word at Lyric Opera - we love each other and work in a harmonious

surrounding,

and that's how you put on the best music.

= = = = = = = = =

- - - -

= = = = = = = = =

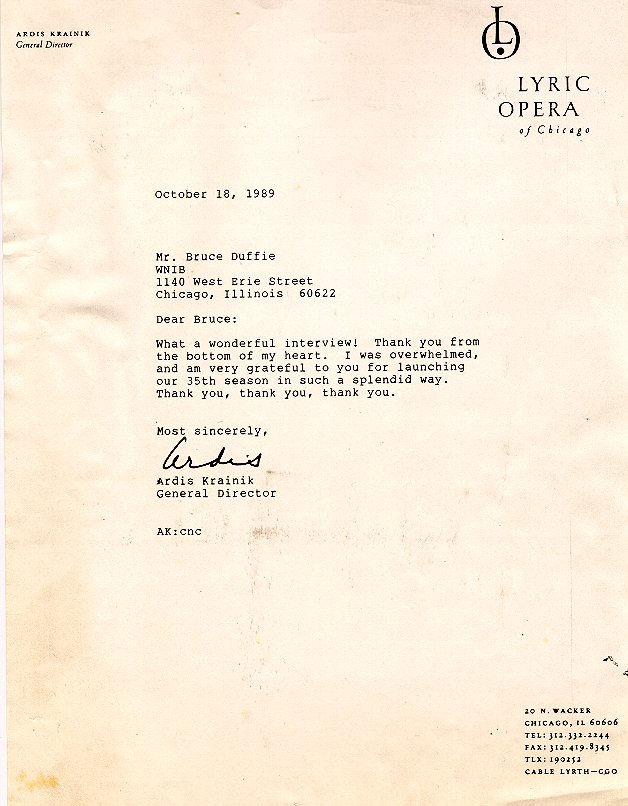

[NOTE: When this interview was published, I

sent Ardis a copy. Her reply to me is reproduced below]

Bruce Duffie, Announcer/Producer with Classical 97, WNIB in

Chicago,

as been a regular contributor to this Journal since 1985. In the

next issue, another administrator - Glynn Ross of the Seattle and

Arizona

Opera companies to celebrate his 75th birthday.

- - - - - - - -

-

- - - - - - - - -

- -

= = = = = = =

- - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - -

- - -

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in her office at Lyric Opera of

Chicago on April 7, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the

following

year.

This transcription was made in 1989 and published in The Opera Journal in issue #3

(September) of that year. Photos and links were added for this

website posting.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.

![]()