Kober did a monthly program on WNIB which introduced his programs,

and played recordings of the music, so I knew him both as a conductor

and as a radio personality. For my own series, I wanted to get his

ideas about the considerations which go into running the orchestra, as

well as probing the musician behind the baton.

Kober did a monthly program on WNIB which introduced his programs,

and played recordings of the music, so I knew him both as a conductor

and as a radio personality. For my own series, I wanted to get his

ideas about the considerations which go into running the orchestra, as

well as probing the musician behind the baton.

Known as the best bassoonist of his generation, Leonard Sharrow had a distinguished career as symphony musician and teacher. Born August 4, 1915 in New York, he was a member of the country's top symphony orchestras from 1935 until 1987, including the NBC (together with his violinist father, Saul Sharrow, under Toscanini), Detroit, Chicago (principal bassoon 1951-64 under Kubelik and Reiner) and Pittsburgh Symphonies. During World War II, he was a member of the all-soldier orchestra for ''This is the Army,'' Irving Berlin's Broadway musical, subsequently made into a film with Ronald Reagan. His 1948 RCA recording of Mozart's Bassoon Concerto stands as the definitive performance of the piece and continues to inspire young bassoonists. He made other solo recordings, in addition to recording with the NBC, Chicago and Pittsburgh orchestras. Highly sought after as a teacher, Mr. Sharrow sent many students on to orchestras and teaching positions around the world. From 1964 until 1977 he taught full-time at Indiana University. He also taught at Juilliard, New England Conservatory, Carnegie Mellon, Pennsylvania State, and numerous summer music festivals in the U.S., Canada, Australia and Japan. Following his retirement, he returned to Indiana, moving to Cincinnati in 1999, and continued teaching until his death on August 9, 2004. |

|

Rudolph Ganz (February 24, 1877 – August 2, 1972) was born in Zurich, Switzerland. He received his initial musical training at the Zurich Conservatory, and in 1899 traveled to Berlin to study piano with Ferruccio Busoni and composition with Heinrich Urban. Although Ganz had made public appearances as pianist and cellist as a child, his debut as a mature artist took place at a concert of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in December 1899, when he performed the Beethoven Emperor Concerto and the Chopin E minor concerto. The following year he conducted the Berliners in his own First Symphony. In 1900, Ganz came to America, and from 1901 to 1905 taught piano at the Chicago Musical College, where he would return as director from 1929 to 1954. After 1905, he made concert tours in Europe and the United States. In 1921 he became music director of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, where he remained until 1927, having led its first recordings for the Victor label. From 1938 to 1949 Ganz conducted the New York Philharmonic’s Young People’s Concerts, and led the orchestra at Lewsohn Stadium during the summer season. He also presided over the San Francisco Young People’s Concerts at this time, and guest -conducted the symphony orchestras of Chicago (where he also frequently appeared as piano soloist), Los Angeles, and Denver. Throughout this remarkably diverse and fruitful career, Ganz remained

a tireless champion of contemporary music, which in his case meant

anything from Saint-Saens, Busoni, or Griffes in the early decades,

to Bartók, Webern, and Cage later on. Ravel

dedicated his most difficult piano piece to Ganz, the “Scarbo” movement

from Gaspard de la nuit. Griffes did the same with his most popular

work, The White Peacock. Rudolph Ganz’s own musical idiom is cosmopolitan,

conservative, and uncommonly witty, as was the man himself.

|

|

After the war he returned to Berlin and spent much of his time working

to rebuild the musical culture of that city by writing compositions for

amateur music groups, choirs, music schools and chamber ensembles, publishing

and serving as a musical advisor. Between 1953 and 1956 he worked

with Bertolt Brecht who had a profound impact on his future compositions.

He also worked with Ernst Busch. He composed in several genres, producing

a cantata for children entitled King Midas. In 1961 he became a member of the DDR Akademie der Künste, where he was head of the music department from 1965 to 1970. From 1962 to 1978 he was president of the East German National Folk Music committee. Between 1973 and 1981 he directed the children’s musical theatre in Leipzig. His awards include an honorary doctorate from Leipzig University (1983) and several state awards. Schwaen’s extensive oeuvre comprises over 620 titles. A number of works, such as the Piano Concerto no.2 (1987), show the influence of his several visits to Vietnam. Later works include the collaborative musical poem Potsdamer Platz (1998). Some of his works were published by the Friedrich Hofmeister Musikverlag. Schwaen later settled in Berlin-Mahlsdorf, where he died at the age of 98. His widow, Ina Iske-Schwaen, maintains an archive dedicated to his works in his Mahlsdorf home. |

|

His compositions have been performed at festivals throughout the U.S.A., in Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Australia, three times at “Moravian Autumn” the Brno International Music Festival in the Czech Republic, and at the Festival Internacional Alfonso Reyes in Monterrey, Mexico. Several of his works, affiliated with BMI, are published by Borik Press (based in North Carolina) and recorded on Centaur Records. His writing has appeared in Perspectives of New Music, In Theory Only, Computer Music Journal, New Grove Dictionary of American Music, and Contemporary Composers published by St. James Press. Co-author with Larry Austin of the landmark book, Learning to Compose (1989), Clark also wrote an aural development textbook, ARRAYS, published in 1992. His most recent book, Larry Austin: Life and Works of an Experimental Composer, was published by Borik Press in 2013. After teaching at The University of Michigan, Indiana University, Pacific Lutheran University, and for 10 summers at the National Music Camp in Interlochen, Michigan, in 1976 Dr. Clark joined the music faculty of the University of North Texas. There he developed the New Music Performance Lab and served as Chair of the Doctor of Musical Arts program and Director of the Center for Experimental Music and Intermedia. He went on to serve eight years as Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and one year as Interim Dean of the UNT College of Music. In those administrative roles, he helped found the Texas Center for Music and Medicine, the Center for Shenkerian Studies, the Artist Certificate in Music Performance program, and the “ASPIRE” programs promoting academic success and student retention. He retired from UNT in 2004 and holds the title Professor Emeritus at that institution. From 2004 through 2008, Clark served as Dean of the School of Music at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, an affiliated campus of the University of North Carolina system. He also served there as Executive Director of the A.J. Fletcher Opera Institute, an exciting professional training program. Serving 2008-2020, Clark led the vibrant School of Music at Texas

State University as Director and Professor of Composition.

The years since 2016 have been unusually productive for him as a composer,

completing more than 30 new pieces.

|

|

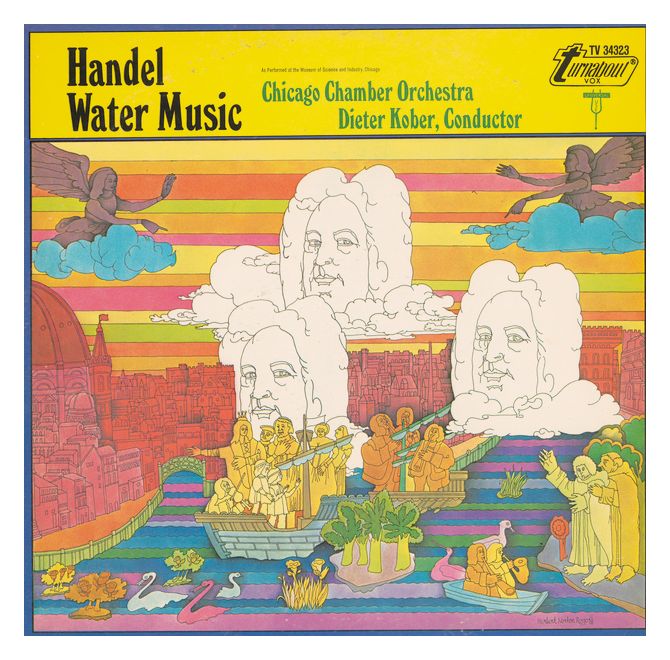

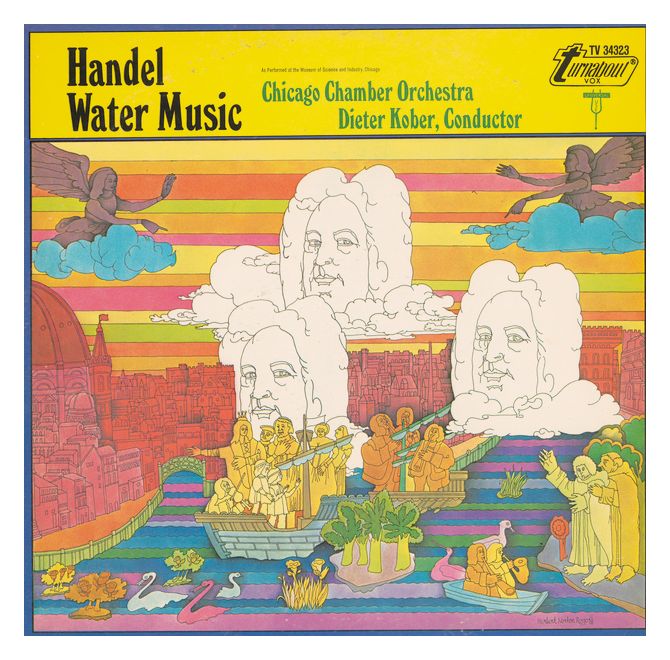

Drawing on over 60 years of tradition as the second oldest professional orchestra in America’s Second City, the New Chicago Chamber Orchestra brings great music to people of Illinois and music lovers around the world. In addition to regular admission-free concerts at the Chicago Cultural Center, the Chicago Chamber Orchestra has performed throughout the United States, Europe and Asia, for radio and television broadcasts and on commercial recordings. The Orchestra, under its now retired founder, Maestro Dieter Kober, was among the first of Illinois’ cultural service organizations to reach across cultural and economic lines, bringing the heritage of great classical music to people from all walks of life, backgrounds and ages. Its “Music for Young Listeners” programs throughout Illinois, have introduced thousands of youth to classical music. The massive repertoire of 5000 compositions from the Baroque to the present, through countless performances featuring internationally renowned soloists, have drawn universal praise, including multiple ASCAP awards and the Orchestra of the Year award from the Illinois Council of Orchestras. Throughout its history, the Orchestra has received kudos from Illinois Governors (famous and infamous), Chicago Mayors, the American Federation of Musicians, and many others: “One of the most notable success stories in Chicago music.” “Winning prestige for Chicago abroad.” “The entire performance has style, pure intonation, accuracy and

a good sense of proportion” “The orchestra displayed a brilliant musical technique, transparency,

flexibility, expressiveness and passion.” “An impressive orchestra with virtuosity and temperament.” “The sound of the Chicago Chamber Orchestra is beautiful, refined

and always in accurate rhythm and intonation.” Now sponsored by Southern Illinois University Carbondale, the New Chicago Chamber Orchestra operates under the musical and administrative direction of Professor Edward Benyas, who was named Music Director Designate in 2002. |

Kober: The orchestra has got better in the past

three years. One reason is because I have better players who

demand more from me as a conductor. I’m much more aware that I

have a responsibility toward the people who put in a great deal of

effort and time and love for the art. So, I have to be better-prepared.

It doesn’t mean that I have to learn the music better, but it means,

for example, that I spend an enormous amount of time now checking the

bowings. I’m very grateful to Charlie Pikler [Concertmaster

of the Chicago Chamber Orchestra, and Principal Violist of the Chicago

Symphony] for helping me to learn more about violin bowings. Frank

Miller [Principal cellist of the Chicago Symphony, who also conducts

the Evanston Symphony] feels that if everybody else in the orchestra starts

a piece with an up bow, and in his opinion it is smart, or cellistically-correct

that the cellists do it the other way, the cellists will do it that other

way. We don’t do this anymore. I check every part, and I

mark every part so that the bowings are uniform. That has helped

us to achieve a certain degree of ‘homogenous

performance’ that has improved. Another

reason is that I tolerate less loyalty in lieu of competency than I

did in the past. Having a stable pool of some one hundred and twenty

musicians, if a good violinist drops out because he can make more money

playing four nights at the Chicago Theater than playing one afternoon

with me, there are others who can come in. I have auditioned everybody.

There was a time when I was just happy to get people to play. Now,

I have a reservoir of auditioned people, which helps make the orchestra

better. Fundamentally, of course, we still fight the financial

shortcomings and insufficient rehearsals, and in my lifetime I hope to

overcome it. But, that means more money...

Kober: The orchestra has got better in the past

three years. One reason is because I have better players who

demand more from me as a conductor. I’m much more aware that I

have a responsibility toward the people who put in a great deal of

effort and time and love for the art. So, I have to be better-prepared.

It doesn’t mean that I have to learn the music better, but it means,

for example, that I spend an enormous amount of time now checking the

bowings. I’m very grateful to Charlie Pikler [Concertmaster

of the Chicago Chamber Orchestra, and Principal Violist of the Chicago

Symphony] for helping me to learn more about violin bowings. Frank

Miller [Principal cellist of the Chicago Symphony, who also conducts

the Evanston Symphony] feels that if everybody else in the orchestra starts

a piece with an up bow, and in his opinion it is smart, or cellistically-correct

that the cellists do it the other way, the cellists will do it that other

way. We don’t do this anymore. I check every part, and I

mark every part so that the bowings are uniform. That has helped

us to achieve a certain degree of ‘homogenous

performance’ that has improved. Another

reason is that I tolerate less loyalty in lieu of competency than I

did in the past. Having a stable pool of some one hundred and twenty

musicians, if a good violinist drops out because he can make more money

playing four nights at the Chicago Theater than playing one afternoon

with me, there are others who can come in. I have auditioned everybody.

There was a time when I was just happy to get people to play. Now,

I have a reservoir of auditioned people, which helps make the orchestra

better. Fundamentally, of course, we still fight the financial

shortcomings and insufficient rehearsals, and in my lifetime I hope to

overcome it. But, that means more money...

Kober: It’s my life. Once you’re in, then

you get the bug. It’s just like blood. Is blood fun? You

can’t live without it. If you come to my rehearsals, you would

think it is fun, because in spite of the fact that it’s strenuous work,

it’s a very human thing, and if you like people and if you love music,

of course it’s fun. Performance, though, is something quite different

from rehearsal. It’s a different kind of strain depending on how

well you feel a piece is ready for performance. I’m sure this

applies to Solti, as well as to the conductor of the smallest provincial

orchestra. When Solti does Moses und Aron of Schoenberg, I’m

sure he’s more apprehensive about it than when he does the Coriolan

overture of Beethoven, which he can do in his sleep.

Kober: It’s my life. Once you’re in, then

you get the bug. It’s just like blood. Is blood fun? You

can’t live without it. If you come to my rehearsals, you would

think it is fun, because in spite of the fact that it’s strenuous work,

it’s a very human thing, and if you like people and if you love music,

of course it’s fun. Performance, though, is something quite different

from rehearsal. It’s a different kind of strain depending on how

well you feel a piece is ready for performance. I’m sure this

applies to Solti, as well as to the conductor of the smallest provincial

orchestra. When Solti does Moses und Aron of Schoenberg, I’m

sure he’s more apprehensive about it than when he does the Coriolan

overture of Beethoven, which he can do in his sleep.I started out in my home town of Chicago in the early 70s, first by going to any and all open mics, piano bars, and hanging out at music clubs, absorbing everything and anything. Chicago was a melting pot of jazz, blues, R&B, folk and rock and roll and had great FM radio stations that became the soundtrack to my young life. While working at a piano bar on Rush Street, I met another young aspiring singer-songwriter, Tony Zito. We formed a band aptly named Frannie and Zoey. Tony and I both wrote songs for the band, but also mixed it up with outside material. I liked learning other people’s songs and being inspired by their chords, melodies and lyrics. We spent two years working together and built a huge following that brought us to the attention of many record companies and several high-profile producers. Unfortunately, the band split up, but it was a great training ground – we played six shows a night, five nights a week, the highlight, performing Tony’s rock opera with the Chicago Chamber Orchestra conducted by Dieter Kober. ==

From an interview of Franne Golde published April 13, 2013 in Kickin'

it Old School blog

*

* * * *

Tony Zito, 48, a composer, lyricist and performer, was a mainstay of the Chicago theater scene for more than 20 years. A resident of the Wrigleyville neighborhood, he died Friday in Illinois Masonic Medical Center after a yearlong illness. Mr. Zito, a member of the first Chicago cast

of ''Hair'' in 1968, won a Jeff Award in 1975 for the original score

of ''Under Milkwood.'' He composed the music and lyrics for ''The Influence

Show'' (1973), ''The Tooth of Crime'' (1973), ''Old Shoulder'' (1978),

''Aaron'' (1979) and ''Bombay Pete'' (1989), in addition to numerous

other productions in Chicago, Buffalo, St. Louis, New York and Washington.

During the last 10 years, Mr. Zito was a frequent performer at Yvette on North State Parkway, where he played the piano and sang. He also made appearances at Yvette Wintergarden on South Wacker Drive. In the early 1970s, he toured the city`s club circuit with two bands: Frannie and Zoey, and Streetdreams. From 1976 until 1980, he was the musical director at Columbia College Theatre. ''He was quite beloved by everyone,'' said June Pyskacek, a Chicago director with whom Mr. Zito collaborated on several shows. ''He had a lot of grace and style. A very original sound as a composer and he had a great voice. ''Musically, he could have a bit of funk in his music that nobody else could do. You could always hear a Tony Zito melody. Everybody pretty much uses the adjective `brilliant.` '' A native of Bellwood, Mr. Zito attended Immaculate Conception High School in Elmhurst. He studied composition at St. Ambrose University in Davenport, Iowa, for two years and graduated from St. Procopius College in Lisle. Mr. Zito spent two years as an Army medic in Vietnam. He is survived by a brother and two sisters. == From an obituary in the Chicago Tribune,

December 20, 1992, by Andrew Gottesman

|

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in the apartment of Dieter Kober in Chicago on September 20, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB a couple of weeks later. This transcription was made at the end of 2021, and posted on this website at the beginning of 2022.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.