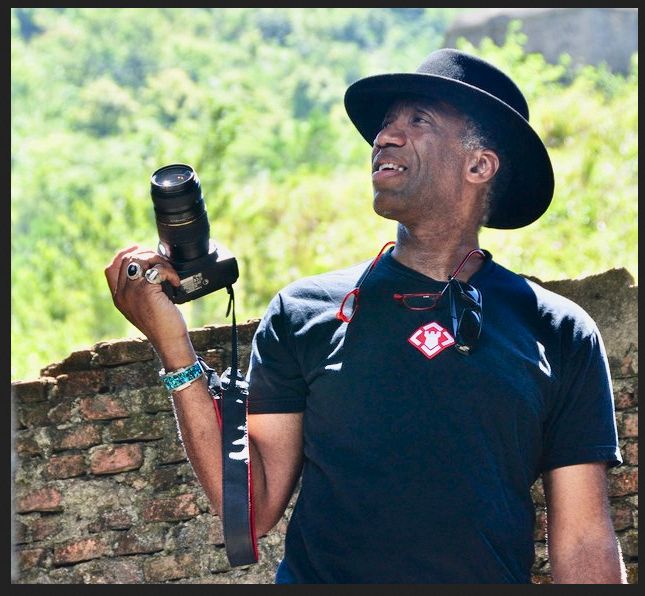

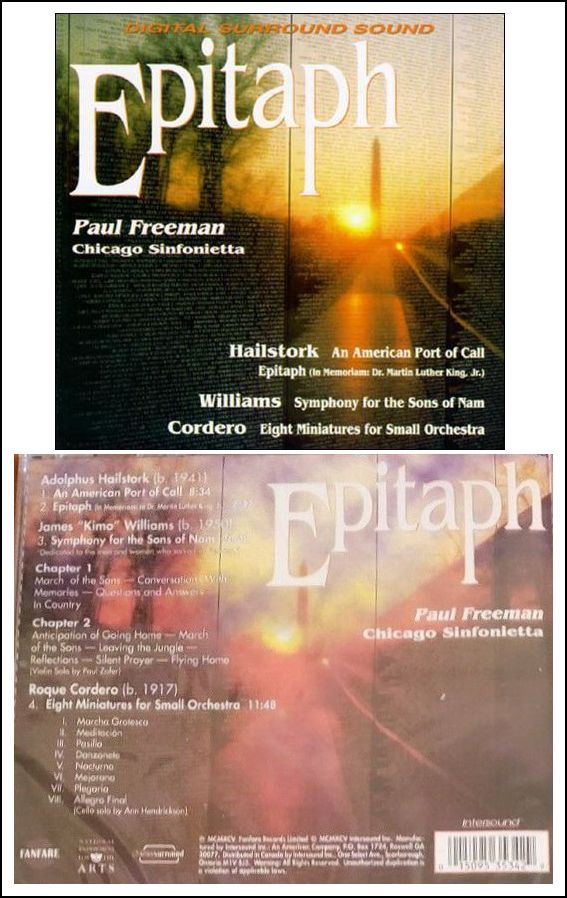

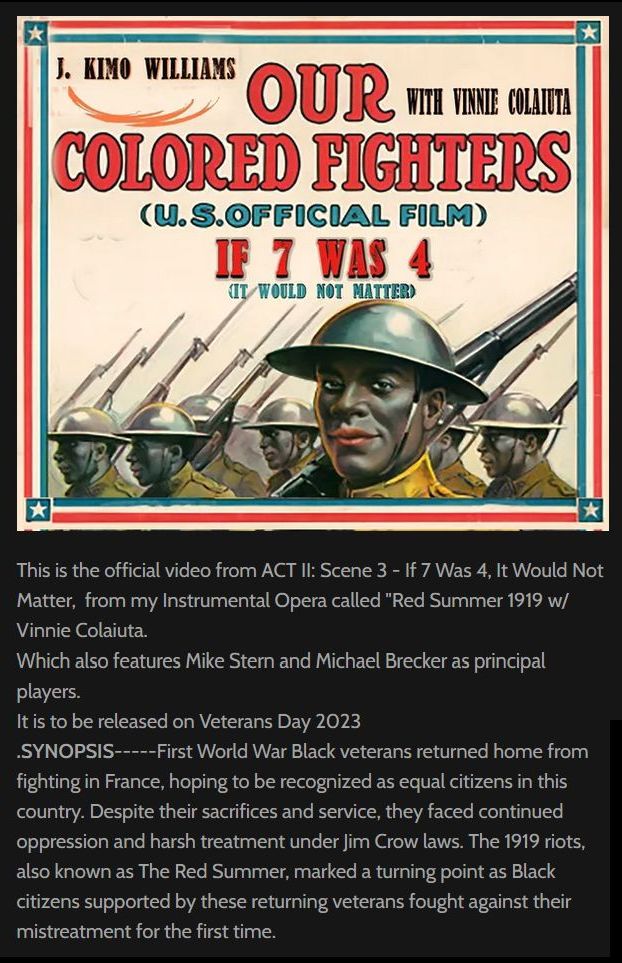

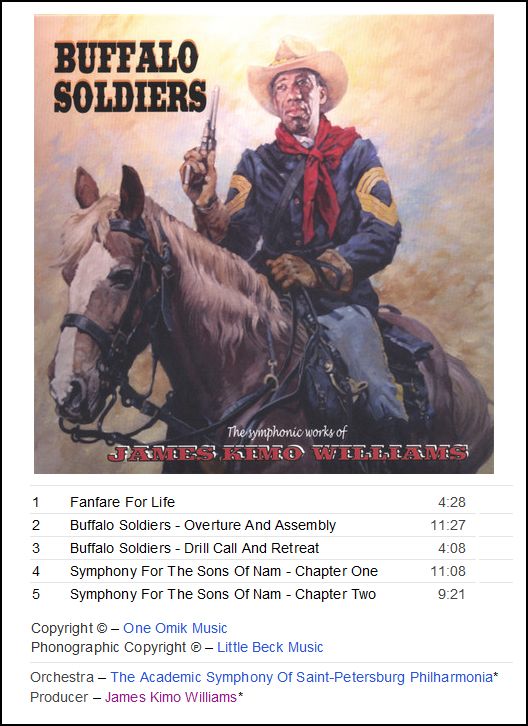

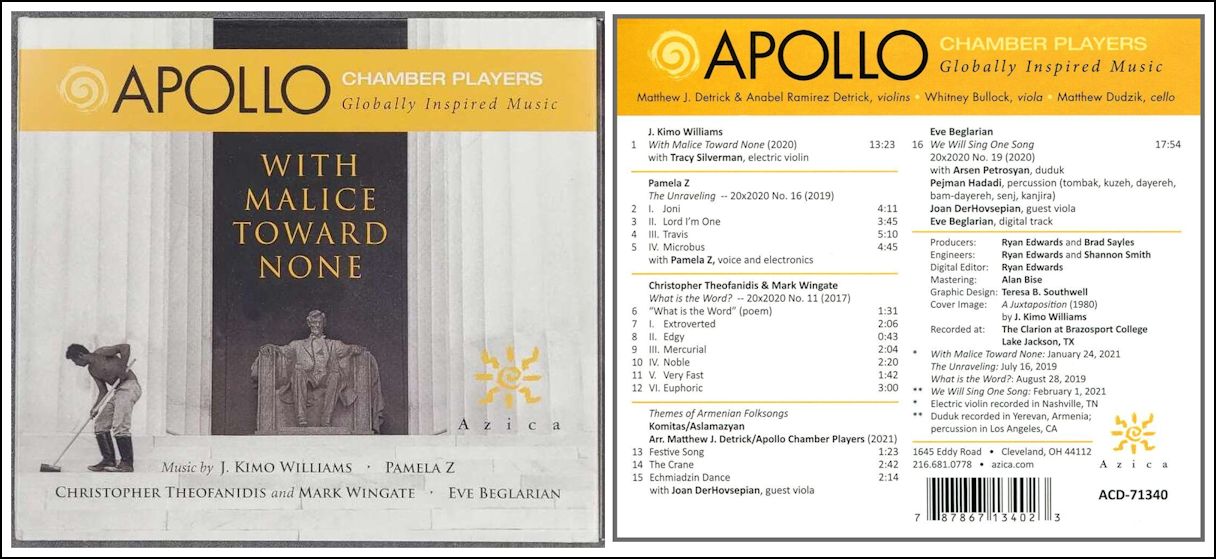

| James "Kimo" Williams

(born January 8, 1950) is an American composer, musician and professor

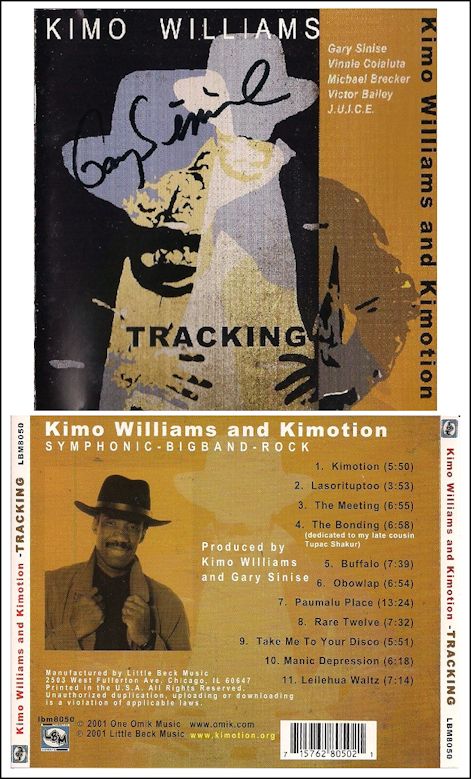

who has performed with a number of ensembles including his ensemble Kimotion

and the Lt. Dan Band, that he co-founded with film/TV actor Gary Sinise

[shown in the photo below]. While he is perhaps best known for his

work with the Lt. Dan Band, Williams has worked on a number of other projects

including award-winning photography, releasing four CDs, writing a stage

play and working on an opera based on the courts martial of Henry Ossian

Flipper, the first black graduate from West Point. Cognizant of the opportunities

he had, as well as those he did not due to a childhood in which he moved

often, Williams speaks to students about his history, their future and their

need to combat mediocrity. Williams was born in Amityville, New York, and spent much of his childhood divided between U.S. Air Force bases, and on his grandparents' sharecropper farm in North Carolina, where he picked tobacco, plowed fields and tended livestock on their rural farm. In 1968, he moved to Hawaii to join his father (a career Air Force Sergeant), and attended Leilehua High School. A dedicated, but inexperienced guitar player, he also took up sports and was an all-star football player with a scholarship invitation from Arizona State. The night before enlisting in the US Army on July 4, 1969, he attended his first major music concert: Jimi Hendrix playing at the Waikiki Bowl. He was so inspired by this concert and the music of Jimi Hendrix, that he dedicated himself to music and playing guitar.

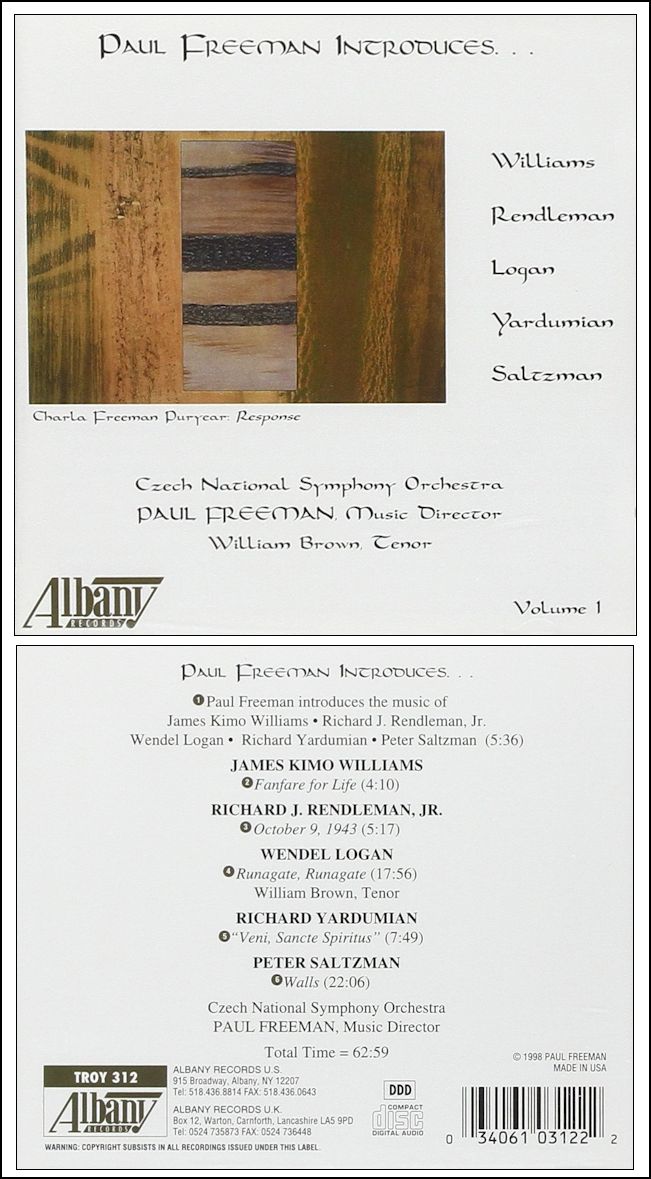

After basic training, he was sent to Vietnam (the day after his 20th birthday), where he served with a unit of the 20th Combat Engineer Brigade in Lai Khe, building roads and clearing land in the jungle. One of Williams' earliest, and most often cited, musical opportunities was in Vietnam when an Army entertainment director heard him play and suggested that he perform for the troops in the field. The Soul Coordinators was born of this request, and started Williams' long resume of performances, both with bands and on his own. After completing his studies at Berklee College of Music and marrying his wife in 1978, the couple together joined the Army Band program, spending a year with the 9th Infantry Division Band at Ft. Lewis, Washington. Kimo went on to attend Officer Candidate School, and was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in 1980. His first assignment brought him to Fort Sheridan, IL: close enough to Chicago that he and Carol could continue producing and performing with his large ensemble (now called “Kimotion”) and their small-group “Williams and Williams”, in local clubs and concert venues. They set up a music publishing company (One Omik Music), as well as launching their own record company (Little Beck Music). To record their music, they rehabbed an old storefront in Chicago, and built and operated a recording studio there. In 1983 he earned his MA in Management from Webster University. When he left the army in 1987 to pursue composing full time he had risen to the rank of captain. He taught at Sherwood Conservatory of Music in Chicago, and in the Music Department at Columbia College Chicago. He completed his military service in the Army Reserves by becoming the Bandmaster for the 85th Division Army Reserve Band, and retired from the Army Reserves as a Chief Warrant Officer in 1996. In 1997, Williams wrote the music for the Steppenwolf Theatre production of A Streetcar Named Desire, leading to his partnership with Gary Sinise, and in 2003, the creation of the Lt. Dan Band (named for Sinise's character in film Forrest Gump). Also in 1997, he directed the Goodman Theatre's production of the August Wilson play, “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom”. In 2008, Williams' Fanfare for Life was performed during the Alabama Symphony's annual musical tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. His compositions include works for chamber ensembles and orchestras, and have been performed by groups worldwide, including the Czech National Symphony Orchestra and the Chicago Sinfonietta. In October 2013 a commission by Williams for the string quartet ETHEL was premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. In 1996, he accepted a position in the Arts Entertainment and Media Management Department of Columbia College. As of 2011 he is a tenured associate professor. Williams was named Chicagoan of the Year in 2006, and was recognized for a lifetime of work including the 1998 founding of the United States Vietnam Art Program. In 1999, he received the Lancaster Symphony Orchestra's Composer Award, and has been the recipient of honors from the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and the Savannah Symphony Orchestra. Buffalo Soldiers, one of his most well-known works, was the result of a commission by The West Point Academy to celebrate their 2002 Bicentennial. In 2007 he was named a Fulbright Program for his works in music, education and history. |

|

The Berklee College of Music is a private music college in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the largest independent college of contemporary music in the world. Known for the study of jazz and modern American music, it also offers college-level courses in a wide range of contemporary and historic styles, including rock, hip hop, reggae, salsa, heavy metal and bluegrass. Since 2012, Berklee College of Music has also operated a campus in Valencia, Spain. In December 2015, Berklee College of Music and the Boston Conservatory agreed to a merger. The combined institution is known as Berklee, with the conservatory becoming The Boston Conservatory at Berklee. Berklee alumni have won 310 Grammy Awards, more than any other college, and 108 Latin Grammy Awards. Other accolades for its alumni include 34 Emmy Awards, seven Tony Awards, eight Academy Awards, and three Saturn Awards. |

| Continental

Harmony, a program of the American Composers Forum and the National Endowment

for the Arts, is the first nationwide music commissioning program in American

history. Beginning as a celebration of the new millennium, people in

every state worked with composers to bring to life new music that reflected

their history, culture, and hopes for the future. Continental Harmony has revealed the vitality of the arts across our land. It has touched the lives of millions of Americans through projects shaped to fit the culture and vision of the people being served. |

Renowned choreographer and dancer Randy Louis Duncan was born on December

14, 1958 in Chicago, Illinois. Growing up and attending public schools

on Chicago’s west side, Duncan’s career began at age fifteen with the

Joseph Holmes Chicago Dance Theatre. Duncan later began formal dance

studies with Geraldine Johnson, followed by classes at the Sammy Dyer

School of Theater, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and Illinois State

University. Duncan credits Harriet Ross and Joseph Holmes with much of

his inspiration.

Renowned choreographer and dancer Randy Louis Duncan was born on December

14, 1958 in Chicago, Illinois. Growing up and attending public schools

on Chicago’s west side, Duncan’s career began at age fifteen with the

Joseph Holmes Chicago Dance Theatre. Duncan later began formal dance

studies with Geraldine Johnson, followed by classes at the Sammy Dyer

School of Theater, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and Illinois State

University. Duncan credits Harriet Ross and Joseph Holmes with much of

his inspiration.Drawing upon ballet, jazz dance, and modern dance for his choreography, Duncan created works that have been performed by numerous dance companies including the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago, River North Dance Company and Gus Giordano Jazz Dance Chicago as well as companies in Seattle and Tel Aviv. In 1987, Duncan choreographed for the first all-African American cast of A Chorus Line. Duncan’s musical theater credits include Guys and Girls, Street Dreams, West Side Story, Carousel, Hello Dolly, and Don’t Bother Me I Can’t Cope. He has taught and judged dance competitions throughout North America, Europe and the Middle East. Duncan’s classes in jazz dance have taken him to Mexico, England, France, Amsterdam, and Israel. Duncan has been a three-time recipient of Chicago’s prestigious Ruth Page Award for Outstanding Choreographer of the Year (1988, 1990, and 1992). In 1994, Duncan won the Jazz Dance World Congress Award. He regularly serves on panels for the National Endowment for the Arts, the Illinois Arts Council, Arts Midwest and the Illinois Arts Alliance. Other awards include the 1999 Artistic Achievement Award from the Chicago National Association of Dance Masters, and the 2000 Black Theater Alliance Award for Best Choreography. An avid supporter of HIV/AIDS causes, Duncan has donated his time and choreography to Dance for Life, creating world premieres for Chicago’s largest dance benefit for HIV/AIDS. His television ballet, Urban Transfer, was produced and distributed nationwide by PBS-TV’s WTTW. Duncan’s first major motion picture by Paramount Pictures, Save the Last Dance, earned him a nomination for the American Choreography Award for dance on film. == Biography from The History Makers

== Photo from the Chicago Academy for the Arts |

|

|

© 2000 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 5, 2000. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.