NJ: That I can’t do at all. I re-record it

again, sometimes, maybe. [Both laugh] Six years I have to wait,

then I can record it at another firm!

NJ: That I can’t do at all. I re-record it

again, sometimes, maybe. [Both laugh] Six years I have to wait,

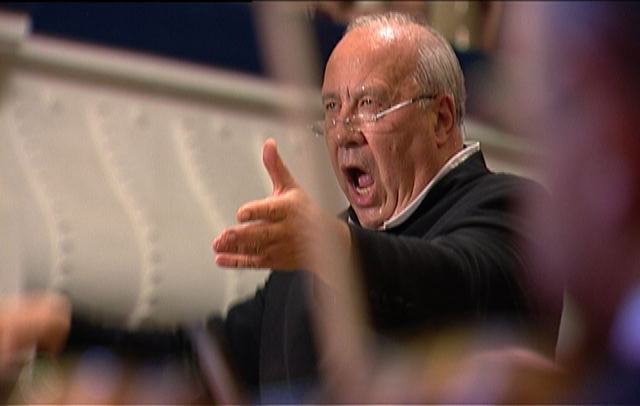

then I can record it at another firm!  NJ: It’s very difficult. The conductor’s place

is not always the best place. And you never know what’s in the hall

at the same time. We played five concerts at the Hong Kong Festival,

and in a conductor’s place there’s not enough expression, not enough forte

from orchestra. But in the hall, it always sounds like full forte.

Your feeling is different from what it really sounds like in the audience.

You don’t know that is going out there.

NJ: It’s very difficult. The conductor’s place

is not always the best place. And you never know what’s in the hall

at the same time. We played five concerts at the Hong Kong Festival,

and in a conductor’s place there’s not enough expression, not enough forte

from orchestra. But in the hall, it always sounds like full forte.

Your feeling is different from what it really sounds like in the audience.

You don’t know that is going out there. NJ: You have to research your scores and music and

tapes and whatever the possibility is to have an idea which kind of music.

For instance, in Tubin’s case, you don’t know very much. You know that

it’s a good composer. You should trust him; must be everything

good. Number Four I did the

first time, Number Five I did and

I did Number Six. It must be

all good, and it was.

NJ: You have to research your scores and music and

tapes and whatever the possibility is to have an idea which kind of music.

For instance, in Tubin’s case, you don’t know very much. You know that

it’s a good composer. You should trust him; must be everything

good. Number Four I did the

first time, Number Five I did and

I did Number Six. It must be

all good, and it was. BD: Yes, minimalism.

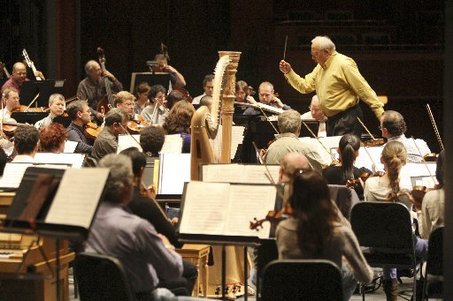

BD: Yes, minimalism. NJ: [Thinks for a moment] It’s difficult to

say. You mean is it show business or something? Entertainment,

it’s a show, yes? That’s a performer’s problem. If you look at

performers, there are show and entertainment performers who make it entertainment,

and others who are doing art. Sometimes they are doing it together.

It’s a very happy marriage where that’s happened. I look at the conductor’s

business, or is that a show business? Depends on who is looking.

Conductors want very much to show the performer how he is looking, how he

is making his performance. It must be outside, something extraordinary,

beautiful. Maybe he is a good-looking man. He is making nice

gestures for the audience.

NJ: [Thinks for a moment] It’s difficult to

say. You mean is it show business or something? Entertainment,

it’s a show, yes? That’s a performer’s problem. If you look at

performers, there are show and entertainment performers who make it entertainment,

and others who are doing art. Sometimes they are doing it together.

It’s a very happy marriage where that’s happened. I look at the conductor’s

business, or is that a show business? Depends on who is looking.

Conductors want very much to show the performer how he is looking, how he

is making his performance. It must be outside, something extraordinary,

beautiful. Maybe he is a good-looking man. He is making nice

gestures for the audience. NJ: Because when I have been booked already and

something else, more interesting comes, and you can’t fix it! [Both

laugh] That’s the thing, especially when you have two orchestras, and

you have duties to serve these two orchestras. Then you have a very

limited time to go to other places, other orchestras. It is interesting

to me to go to Chicago, to Berlin Philharmonic, to different orchestras.

It made me sad to have to say for Berlin Philharmonic, “No, I can’t come.

I can’t come.” Better to have free time, a little bit. That is

why I now just give up my orchestra, Scottish National Orchestra, and I am

a little bit having free time and have more engagements here in America.

I like very much America to live with my family together, which is also important.

I have three children, and I don’t see them very much.

NJ: Because when I have been booked already and

something else, more interesting comes, and you can’t fix it! [Both

laugh] That’s the thing, especially when you have two orchestras, and

you have duties to serve these two orchestras. Then you have a very

limited time to go to other places, other orchestras. It is interesting

to me to go to Chicago, to Berlin Philharmonic, to different orchestras.

It made me sad to have to say for Berlin Philharmonic, “No, I can’t come.

I can’t come.” Better to have free time, a little bit. That is

why I now just give up my orchestra, Scottish National Orchestra, and I am

a little bit having free time and have more engagements here in America.

I like very much America to live with my family together, which is also important.

I have three children, and I don’t see them very much.| Born: June 7, 1937 - Tallinn,

Estonia The Estonian conductor, Neeme Järvi, was brought up within the USSR's system for developing musical talent, Järvi studied percussion and conducting at the Tallinn Music School. He made his debut as a conductor at the age of eighteen. From 1955 to 1960 he pursued further studies at the Leningrad Conservatory, where his principal teachers were Nikolaï Rabinovich and Yevgeny Mravinsky.  From the early 1960's, Neeme Järvi took a leading role in the musical

life of his homeland. He was the co-founder of the Estonian Radio Chamber

Orchestra in Tallinn and its artistic director. In 1963 he assumed the directorship

of the Estonian Radio & Television Orchestra, his first important post.

He also founded the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra. He was also asked to become

the principal conductor and artistic director of the State Academic Opera

and Ballet Theater of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (renamed Estonian

National Opera Theater after restored independence of Estonia), and held

this post for 13 years. From 1976 to 1980 he was chief conductor and artistic

director of the Estonian State Symphony Orchestra, then in its infancy. By

the late 1970's his fame had spread throughout the Soviet Union and Eastern

Europe, and he received favorable notices for his appearances in the West.

He made history by leading the first performances of Strauss' Der Rosenkavalier and Gershwin's Porgy and Bess ever given in the USSR.

In 1979, he conducted Tchaikovski's Eugene

Onegin at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.

From the early 1960's, Neeme Järvi took a leading role in the musical

life of his homeland. He was the co-founder of the Estonian Radio Chamber

Orchestra in Tallinn and its artistic director. In 1963 he assumed the directorship

of the Estonian Radio & Television Orchestra, his first important post.

He also founded the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra. He was also asked to become

the principal conductor and artistic director of the State Academic Opera

and Ballet Theater of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (renamed Estonian

National Opera Theater after restored independence of Estonia), and held

this post for 13 years. From 1976 to 1980 he was chief conductor and artistic

director of the Estonian State Symphony Orchestra, then in its infancy. By

the late 1970's his fame had spread throughout the Soviet Union and Eastern

Europe, and he received favorable notices for his appearances in the West.

He made history by leading the first performances of Strauss' Der Rosenkavalier and Gershwin's Porgy and Bess ever given in the USSR.

In 1979, he conducted Tchaikovski's Eugene

Onegin at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.While with the ESSO Neeme Järvi developed a particular interest in unearthing and performing neglected repertory by both little-known and important composers. He was a particular champion of the Estonian composers Eduard Tubin and Arvo Pärt. In 1979 he premiered Pärt's Credo, a work that represents a turning point in that composer's stylistic evolution. Järvi, recognizing the importance of Credo (which incorporates biblical texts), presented it without first navigating through the usual channels of the Communist Party or the Composers' Union.The resulting controversy and official disfavor induced Järvi to emigrate. Neeme Järvi was permitted to leave Estonia, and in January 1980, he and his family emigrated to the USA. Two major agencies, International Concert Management and Columbia Artists, had offered him contracts and he decided to go with Columbia Artists. Within a month of his departure, he made his debut performances with the Boston Symphony, the Philadelphia Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, and Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. He quickly received important appointments: principal guest conductor of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra in England (1981-1983), music director of the Royal Scottish Orchestra (1984-1988), music director of the Gothenburg (Sweden) Symphony Orchestra (from 1982), and principal guest conductor of the Japan Philharmonic. In recognition of his service to the Scottish orchestra, Aberdeen University bestowed upon him an honorary doctorate. In 1990, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra honors Neeme Järvi by naming him Conductor Laureate for Life. Since 1990, he has been the musical director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. In addition, he is the first principal guest conductor of the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra. Since 2000, he has held international master classes in the summer resort town of Pärnu, Estonia. Neeme Järvi is among the most recorded conductors in the world. Since 1983, 357 CDs have been produced under his baton. During the last ten and a half years, he has given 1119 concerts in 125 cities, conducting 72 different orchestras. With the Detroit Symphony Orchestra he has made thirty of some 100 recordings on the Chandos label. Järvi has also recorded for BIS, Deutsche Gramophon, and Orfeo; his various recording projects include cycles of orchestral music by Sibelius, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Tubin, Brahms, Schumann, Shostakovich, and others. Neeme Järvi's children have made their mark on the musical world as well: son Paavo Järvi is gaining an international reputation as a conductor and holds posts as principal guest conductor of the Stockholm Philharmonic and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Kristjan is the founder and conductor of the Absolut Ensemble of New York City; and daughter Maarika is principal flutist with the RTVE Symphony Orchestra in Madrid. Järvi announced his decision to step down from his Detroit post in 2005. He has also served as principal conductor of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. |

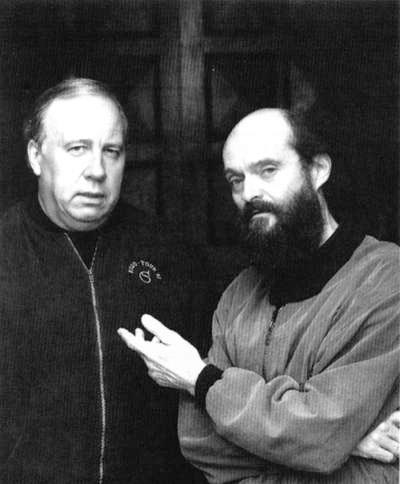

This interview was recorded in Chicago on December 14, 1987.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1989, 1990, 1991, 1997,

and 2000. This transcription was made in 2009 and posted on this website

early in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.