|

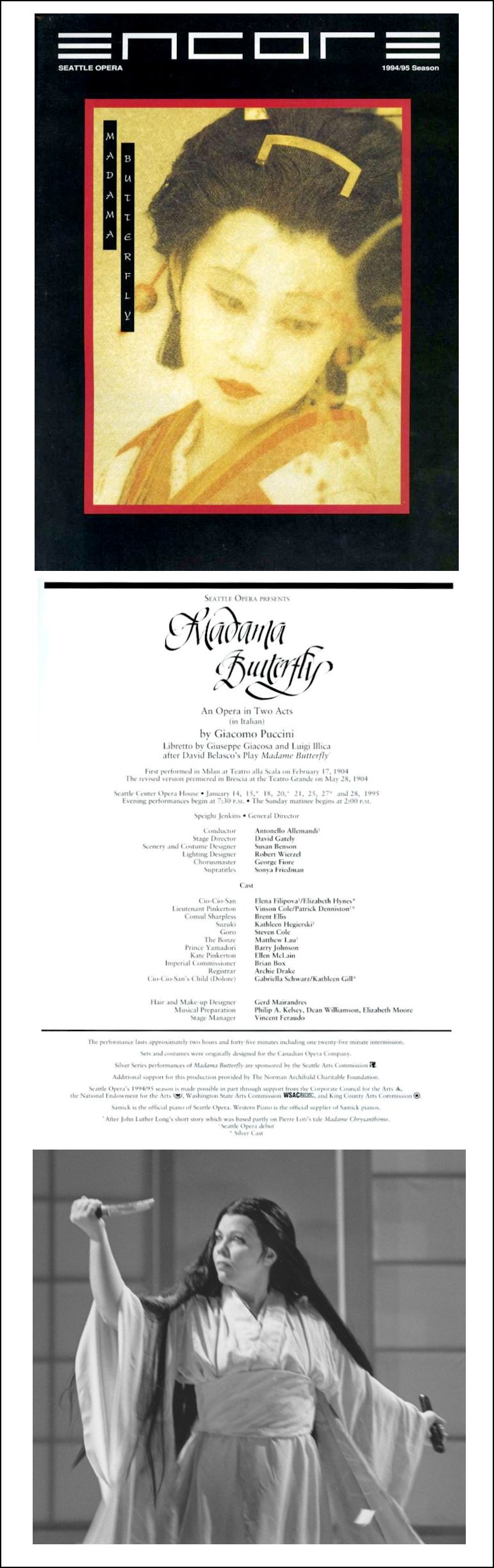

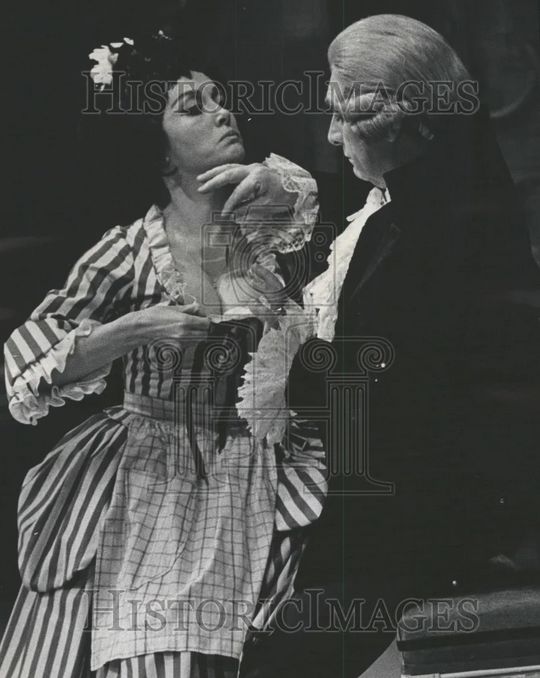

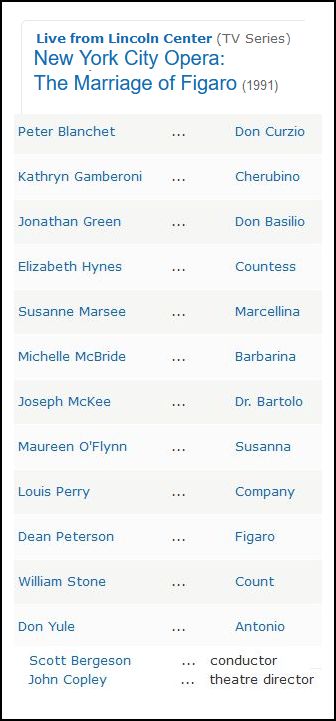

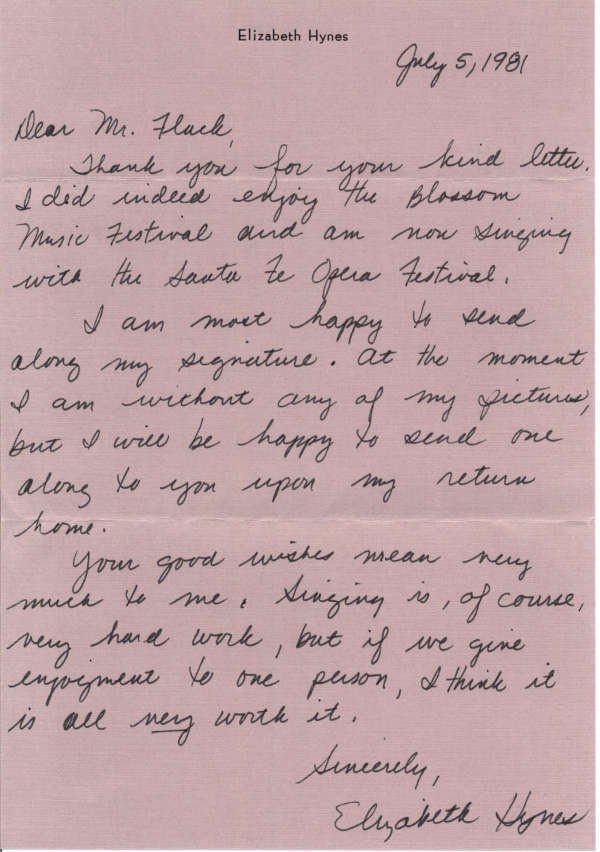

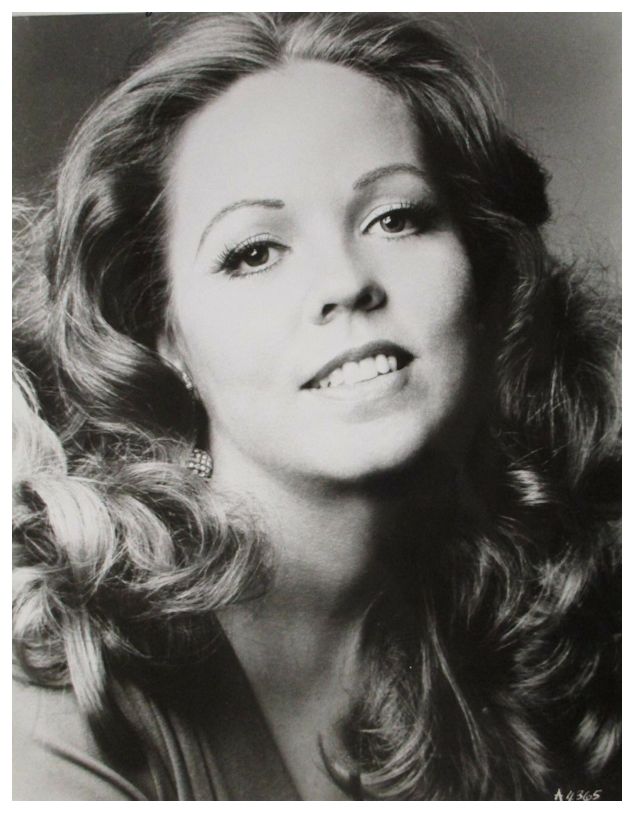

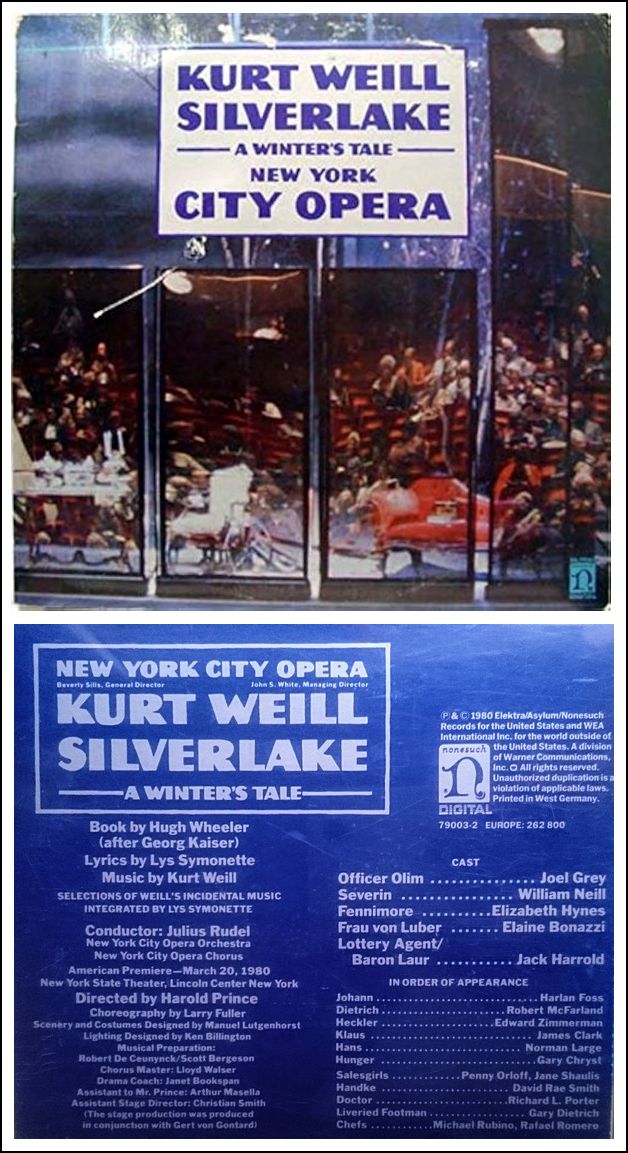

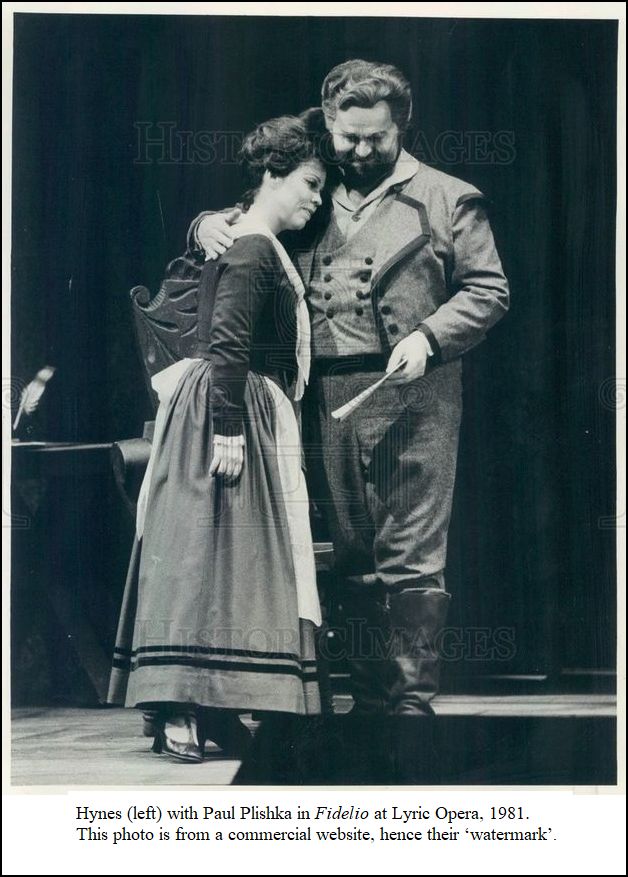

Elizabeth Hynes has been a faculty member at the USC Thornton School of Music since 1995, and served as Chair of the Vocal Arts/Opera Department from 2005-2012. Ms. Hynes has taught at the Aspen Music Festival and School since 2003. She was elected to the Aspen Music Festival Corporation in 2005 and has twice served as a New Horizons Faculty, endowing three students for three years study at the Aspen Opera Theater Center. Ms. Hynes has also taught at the Oberlin in Italy program in Arezzo, Italy. With a national reputation as a vocal teacher and mentor, Ms. Hynes adjudicates regularly for the Metropolitan Opera Auditions and is in demand as a master class presenter around the country. Her students are consistently among winners of major competitions, and appear frequently with professional opera companies and orchestras throughout the United States. Ms. Hynes has performed in major opera houses around the world, singing some of opera’s most demanding roles such as: Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, Mimi in La Bohème, Marguérite in Faust and the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier. As Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, Ms. Hynes has been heard at the Theatro Teresa Carrena in Caracas, Venezuela, New York City Opera, Washington Opera, Vancouver Opera, San Diego Opera and Seattle Opera, among others. The Seattle Times Review read, “…Elizabeth Hynes, is a passionately intense Butterfly, with a multi-dimensional portrayal in which no expressive detail is overlooked. This is an important voice, one of extraordinary and compelling beauty. Hynes generates a real radiance in the role; she illuminates the emotions and makes you believe in them.” Throughout Ms. Hynes’ career, she has been recognized for her interpretation of Mozart roles, appearing frequently as Susanna, and Pamina. Her portrayal of the Countess in the PBS Live from Lincoln Center broadcast (September 25, 1991) of Le Nozze di Figaro gained public and critical acclaim and she made her European debut at the English National Opera as Donna Elvira. A sought-after concert artist, Ms. Hynes has appeared with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Georg Solti, and the orchestras of Cleveland, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Seattle, St. Louis and Los Angeles, among others. She has sung with the orchestras of Madrid, Barcelona, Vancouver and New Zealand, and with the Tonkünstler Orchestra of Vienna on two American tours. Vocal performances on the USC campus include: Mahler’s 4th Symphony, Britten’s War Requiem and Górecki’s Third Symphony with the composer conducting. Ms. Hynes can be heard in the role of Fennimore on the Nonesuch recording of the American Premiere of Kurt Weill’s Silverlake and in the role of Wellgunde in Das Rheingold on the archival Chicago Symphony recording: The Solti Years, Chicago Symphony Orchestra – Georg Solti, cond. At the beginning of her career Elizabeth Hynes was the recipient

of the National Opera Institute Grant, William Sullivan Foundation

Grant, the Liederkranz Foundation Scholarship, and served as an Affiliate

Artist with the Ft. Worth Opera for three years. == Biography from the USC Thornton School of

Music website (with corrections) |

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 9, 1982. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.