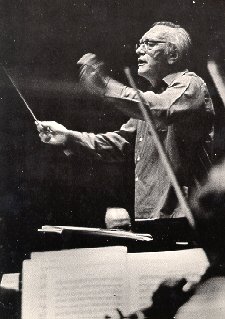

Composer Karel Husa

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Composer Karel Husa

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

This past August, the Pulitzer Prize winning composer Karel Husa celebrated his 80th birthday, and there were (and still are) concerts being given all over the world to honor this occasion.

Born in Prague, Husa studied there and in Paris with, among others, Arthur Honegger, Nadia Boulanger, Jaroslav Ridky, and conductor André Cluytens. In 1954, Husa was appointed to the faculty of Cornell University where he was Kappa Alpha Professor until his retirement in 1992. He was elected Associate Member of the Royal Belgian Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1974 and has received honorary degrees of Doctor of Music from several institutions, including Coe College, the Cleveland Institute of Music, Ithaca College, and Baldwin Wallace College. He has conducted professional and student orchestras all over the world, and several of his works have been recorded commercially and are in the current catalogue.

It was in February of 1988 that Karel Husa was in Chicago for the world

premiere of his Trumpet Concerto, written for Adolph Herseth and the Chicago

Symphony. Just before the first performance, the composer sat down with

me for a chat at his hotel. Here is much of what was said that afternoon.....

Karel Husa: I was at the rehearsals. It was an immense experience for me. You know, sometimes I conduct my music for the first time and this time I didn't, so I can see how things are progressing. I think it's going very well. Mr. Herseth is terrific, and Sir Georg and the orchestra are incredible.

Bruce Duffie: Is it better if you conduct your work for the first time, or let someone else do the premiere?

KH: I think that I prefer others to conduct my music. It

just happened in the past that I conduct it myself. I like to conduct

my music, but I also learn from others many things that I haven't thought

of.

KH: I think that I prefer others to conduct my music. It

just happened in the past that I conduct it myself. I like to conduct

my music, but I also learn from others many things that I haven't thought

of.

BD: When you conduct your own works, are you better at it because you also conduct works by others?

KH: I don't know. I would say that to conduct my own music it's more authentic, but a composer doesn't live by conducting his music. It has to be conducted mostly by others. When I was a student in the conservatory, I thought about conducting. It was offered at the same time as composition, so it was convenient and I saw that when I started to conduct my own music, it would be easier especially when I was young. When you're just starting out, it's difficult to be performed, and to have a conductor learn a piece of music just for one performance can be impractical. So a composer can demonstrate it very well.

BD: Now, when you conduct a work you wrote many years ago, do you have to approach it as if it was brand new?

KH: In a sense, but I have a feeling that I know the piece. Once I've conducted it or have heard it, I know it. Before that, I don't.

BD: Are you ever surprised by what you hear?

KH: There are times, yes. It happens both ways - sometimes I miscalculate, and other times it sounds even better than I thought. But those surprises are not very big.

BD: Is it safe to assume that you've been pleased with most performances you've heard of your music over the years?

KH: It sounds a little narcissistic, but yes, I would say so in general. There are some circumstances that your music gains because another conductor or performer has a different view and may embellish your music more than you would dare to. When I am on the podium and speak about "my music" or "my work," it sounds a little too big. One has to keep some modesty and not overdo it in front of the orchestra. I usually didn't rehearse my music too much because of that. When you have a soloist, you have to give time to them for their performance, and if you don't rehearse the standard work(s) on the program, the orchestra will somehow feel abandoned.

BD: Then your piece gets short-shrift?

KH: I feel that I don't have to give as much rehearsing, but rather show in the actual concert what I really thought.

BD: Speaking as conductor, do you do all of your work at the rehearsal, or do you leave a little bit for the moment of performance?

KH: Due to the shortness of rehearsal time, especially with

orchestra, it usually happens that one leaves enough - and often a lot -

for the concert. That depends, also, on the quality of the group.

I have conducted young ensembles in the high school or university where the

situation is completely different from a professional orchestra. But

there is practically never a time when the conductor can say, "We've accomplished

enough" and not have rehearsal the next day. That doesn't exist today.

But something special happens in the concert, hopefully. It might also

be like Berlioz describes in his concerts, but in general I get the feeling

that it's something special.

* * * * *

BD: You've been teaching for many years. Is there any real difference between the students of today and those when you started out?

KH: I think so. They are better-equipped and maybe smarter

in general. They know more and have the advantage of hearing much more

music than I have heard. They have access to excellent recordings and

scores. As a composer, one learns the most from scores, so technically

they are very good. The ideas, or the inspiration, is probably the same

as it was, but technically, they are better prepared. And the performers

are better, I think. They have to be because they live in a constant

competition. If you want to get into a school of music today, you have

to be very good and they only accept a certain number. Then after

you finish school, again you are in competition when you look for a position.

For a composer-position in a university today, there will be easily 120 applicants.

KH: I think so. They are better-equipped and maybe smarter

in general. They know more and have the advantage of hearing much more

music than I have heard. They have access to excellent recordings and

scores. As a composer, one learns the most from scores, so technically

they are very good. The ideas, or the inspiration, is probably the same

as it was, but technically, they are better prepared. And the performers

are better, I think. They have to be because they live in a constant

competition. If you want to get into a school of music today, you have

to be very good and they only accept a certain number. Then after

you finish school, again you are in competition when you look for a position.

For a composer-position in a university today, there will be easily 120 applicants.

BD: Is that perhaps too much competition?

KH: Oh yes. It's very, very tough, and to a certain degree it's too much. We are too many for the few positions that exist.

BD: What advice do you have for all of these graduates you're turning out in composition?

KH: Well, it was always hard, but it is very difficult. I was told by my teachers that you couldn't live from composition or from teaching composition. We had to be prepared to do something else. Even before they are accepted, I point out the number of people who get positions against the number of those who apply.

BD: Then once they've been accepted, they've already cleared a huge hurdle.

KH: That's true. And the competitions for an orchestral

position have at least as many applicants. They don't audition all

the applicants, but they invite certain people. But everyone who applies

must think that he or she will be one of those who probably will be invited.

* * * * *

BD: As teacher and composer and conductor, how do you balance the three sides of that triangle?

KH: Somehow I try and it works out. The university gives the composer a lot of leeway as a teacher. If I miss one week, I make up my lessons the next week. Until now, I have worked it out, and I have about three more years to teach so I think I will be all right.

BD: Would you balance the legs of the triangle differently if you could?

KH: No. I like all three of them - certainly composing the most - but I like the three of them so much. If I had to choose only one, I would compose. But the problem of only composing is to be always at home writing, and I wouldn't be able to stand it for long. To sit and write music and be by oneself, and be at the table or go to the piano all day long... I couldn't do it. It's a very tiring profession in the sense that the blood cannot circulate. I'm not a gymnast, but one has to do something else. I have to go and I have to speak to people and I have to see what other people think. That's my contact. As a teacher, it's advantageous to have students come and show you and speak to you about other music. That way, you don't get closed off.

BD: Is it a mistake for a composer to closet himself or herself?

KH: People have different characters. I also feel that as

a conductor, performing music is magic to me. I need the outlets to

all of that.

KH: People have different characters. I also feel that as

a conductor, performing music is magic to me. I need the outlets to

all of that.

BD: Then here's the big question: What is the purpose of music in society?

KH: That's a very difficult question. I hope I can answer... When I was 17 or 18, I went for the first time to a concert. I went to art exhibitions because I was interested in it. I had been reading poetry because I loved it. That first concert was a violin and piano recital of the Kubeliks - Jan accompanied by his son Raphael. At the time, Jan was over 60 years old, and it was an amazing experience for me to go to a concert and hear music. A week later, I bought a ticket to an orchestra. Before that, I had the impression one couldn't go to a concert without being properly dressed, which meant having a tuxedo. I felt it was only for the highest society. But I went, and the impression I got from the music - which I didn't understand - was overwhelming. So the purpose, I guess, is the communication. The sounds poured on me and soaked in. Then to see the players perform, that is something I have always admired. It's something that can lift me, even at my age. I am sometimes moved to tears when I hear passages, and that is amazing.

BD: Do you get the same feeling when you listen to your own music?

KH: No. These days, I am too scared. In general, I am worried and nervous about it, so I'm not so free. When I listen to my music in concert - for instance the Music for Prague which I've heard numerous times - I'm a little impatient because I know it a little too well. I have the impression that the audience who are listening find it too long or boring.

BD: But you wouldn't go back and make changes in the score?

KH: No. In the end, I don't think that the piece is too long, but it's just the impatience of somebody who has heard it too often.

BD: Perhaps you should just show up when the final notes are sounding!

KH: No, no. I still like it, but that's the feeling.

BD: Some of your pieces have different versions. For instance, Music for Prague was written for band and later scored for orchestra. Is it two different pieces, or just one piece in two versions, and how do they differ?

KH: I would say in that case, it's one piece in two versions. It was originally commissioned for band. In 1968, I had a commission to write a piece for wind ensemble at Ithaca College. At that time, the events happened and I saw that it would be a terrific vehicle with the power of the winds plus percussion. Later, I was going to guest-conduct in Europe and America, and I thought I'd make a transcription of it myself. That's how it started. I didn't expect that it would be played so often by orchestras, but it is. That's a nice feeling.

BD: Is one or the other version better?

KH: No, I would say they are two children of mine and I like them both.

BD: Like twins?

KH: Perhaps, yes. Sometimes, one child is more impressive

in one concert, and other times, the other child is more impressive in its

concert. If the orchestra is powerful and has a large string section,

then the sound is very good. If the string section is smaller, then

it can be overpowered by the winds and percussion. You might think I'd

prefer the orchestra version because bands are not usually professional organizations,

but I have heard some very moving performances by young bands, even all-state

high school bands which were really excellent.

* * * * *

BD: You get many commissions. How do you decide which to accept and which to set aside?

KH: I wouldn't say that I get too many commissions, but it has worked out that I could accept many. When I was approached a year and a half ago to write a concerto for Mr. Herseth and the Chicago Symphony with Maestro Solti, there's not a choice to make. You have the perfect commission there can be. It was the same when I was approached by the New York Philharmonic. When I was younger, I was not approached by these great ensembles, so I accepted most things that were offered. Today, it's a little different because there are young composers with impressive amount of commissions. That stems from organizations like Meet the Composer, who try to arrange things. Also the National Endowment for the Arts. That helps. In fact, I think that life for composers today is very good. There are outlets and they can get commissions and be performed. Of course, one has to be ‘good' . . .

BD: Then let me ask that question - what contributes to being a ‘good' composer?

KH: Ideas, definitely. Many scores will be refused by conductors and members of committees on the basis that they are technically not as good yet. It would be like writing a proposal and making grammatical mistakes. That would be terrible, and the same thing is true in music. If a composer writes things that are impossibly wrong, or which don't exist, that's how they start to eliminate some works from the stack.

BD: As Music Director of orchestras, is this how you select which pieces you will and will not put on various programs?

KH: I am only a guest conductor, but in the past I have been a member of some committees, and yes, it's true. If there is a competition for composers, there will be 500 or 600 scores. Another committee will be there to eliminate those which are not technically very good. They will have many good scores, and one has to arrive at a small number to make the final selection.

BD: When putting together symphonic programs, how do you balance the old works with new ones?

KH: I like to do that. I like to play one modern composition

in every program. I think the audience will not rebel against that.

They may not like the piece, but they accept it and this is not a new idea.

I remember Charles Munch in Europe and Talich in Prague and many others

always had a modern piece in subscription concerts. I think it has

to be. Composers have a very difficult task. We are competing

against music of 300 or 400 years. Performers are different.

They only compete against other performers who are alive for the slot on

the schedule. When selecting a soloist, they are the ones who are available

to perform. When selecting music to play, they take Beethoven and all

the rest, and eventually there is no place for the living composer.

KH: I like to do that. I like to play one modern composition

in every program. I think the audience will not rebel against that.

They may not like the piece, but they accept it and this is not a new idea.

I remember Charles Munch in Europe and Talich in Prague and many others

always had a modern piece in subscription concerts. I think it has

to be. Composers have a very difficult task. We are competing

against music of 300 or 400 years. Performers are different.

They only compete against other performers who are alive for the slot on

the schedule. When selecting a soloist, they are the ones who are available

to perform. When selecting music to play, they take Beethoven and all

the rest, and eventually there is no place for the living composer.

BD: But aren't the performers competing against the memories and recordings of the past?

KH: In a sense, but the orchestra cannot engage Heifetz any more. To get a sold-out performance, the might do only Beethoven, Brahms, Bach, and the audiences will definitely will come.

BD: What do you expect of the audience that attends one of your works - either an old one or a world premiere?

KH: I expect that they listen to the piece and not compare it to the style of Handel or Bach or Beethoven because I don't write in that style. I admire those composers so much and they have done it so well that I cannot compete with them on that level. But Beethoven didn't write like Handel. It was a completely different style, just as painting is not only Rembrandt, Da Vinci, Raphael. They are only part of the whole literature that we have. If I had been born in Asia, my concept of art would have been very different. If I'd been born in Mesopotamia behind Turkey, I might say my style of art is truly beautiful and I don't need Beethoven. It would be wrong again, but it shows that these composers were not part of a culture in other countries.

BD: So you are encouraging the expansion of everything.

KH: Yes, of all arts. Not too long ago, we didn't think of music as anything other than European. Today we are interested in Javanese music and the culture of Tibet and many, many things.

BD: It's a good thing to always learn more?

KH: I think so. One has to learn constantly.

BD: In music, where is the balance between the artistic achievement and an entertainment value?

KH: I really don't know. I often wonder where that is. When I go to a concert, I don't think of it as entertainment. I think that it will enrich me in some way. Entertainment, as wonderful as it is, doesn't come too much to my mind. I like to hear light pieces, too, and there are some beautiful excerpts from larger works I played on the violin. When I was a student in Prague, I was at a concert or an opera practically every day. I remember how touched I was by hearing operas and operettas that others considered simple. I took everything at its highest value.

BD: Why didn't you write operas?

KH: I didn't have the chance. I would have loved to, and maybe it's not too late for me. All music has some function. I like to hear a light overture, but I also like to hear something substantial in a concert. The problem is that some audiences come to a concert tired after a day's work, and they would like the music to entertain them. Many times that doesn't happen because the composer wants to be serious. We can't always write music just to entertain people. It's amazing to say this because I've written some pieces which I call divertimento. That word means to entertain. They are short pieces and I've had so much critique that they are too simple.

BD: But you do like them just the same?

KH: I do like them because I like to laugh and be happy and even talk nonsense sometimes.

BD: You've not written an opera, but you have written for the voice. Tell me the joys and sorrows of writing for the human instrument.

KH: I've not written much, and the reasons are practical.

By the time I thought I would like to write for voice, I left Prague and went

to Paris. So I had to capture and learn about the French language.

I read many French poets and would have liked to set them, but I wasn't ready.

Then I left and came to America and I thought I'd better wait before writing

in English. I did set 12 Moravian Songs for voice and piano, but that

used a Moravian text and it was translated. Then I set some Henry David

Thoreau, whom I admired, and I've also written An American Te Deum

which is about 46 minutes. That was for chorus and it was a great experience.

KH: I've not written much, and the reasons are practical.

By the time I thought I would like to write for voice, I left Prague and went

to Paris. So I had to capture and learn about the French language.

I read many French poets and would have liked to set them, but I wasn't ready.

Then I left and came to America and I thought I'd better wait before writing

in English. I did set 12 Moravian Songs for voice and piano, but that

used a Moravian text and it was translated. Then I set some Henry David

Thoreau, whom I admired, and I've also written An American Te Deum

which is about 46 minutes. That was for chorus and it was a great experience.

BD: Some of your music has been recorded. Is it special to get a broader audience in this fashion?

KH: I guess it's one of the ways that a composer is known, but a concert is something that really happens. That live experience lets me feel things and be in the middle of things. But recordings are a wonderful help to the composer to be heard on radio and in homes all over. That's part of what life is today.

BD: Are you basically pleased with the recordings that have been made?

KH: Yes, I think so in general. The recording which the old Fine Arts Quartet made of my Second and Third Quartets I still think is just terrific. I conducted a recording of the University of Michigan Band of Music for Prague and Apotheosis, and just yesterday I spoke with one of the Chicago Symphony brass players and he said it was one of his favorites! When you record with a school or university ensemble, you think it's not as good or not on the professional level, but this was a live concert and not a recording session. The Alard Quartet did my First Quartet, and the Verdehr Trio did the Sonata a Tre and I'm most pleased.

BD: Is there ever a chance that the records can be too technically perfect because of the cut-and-splice?

KH: That is true. That has happened in recordings earlier

in my career. In 1954 in Paris we did Bartok's Miraculous Mandarin.

We had to make about 20 or 25 splices because we would rehearse and record

the first five minutes of it, then we took the next four or five minutes

and made two or three versions of each. But we had to splice it because

sometimes a mistake would happen and people would look for the mistakes

in recordings. Perhaps today one doesn't do it as much, but after maybe

30 splices, it was very good. I also did the Brahms First Symphony,

and was supposed to do the Prokofiev Cello Concerto, which is a symphony

in itself, but that was when I received a letter from Cornell asking if I

was interested in coming to the US for three years to teach composition.

So, I abandoned the project because I was a composer first.

* * * * *

BD: Where is music going today?

KH: The fastest and the best description would be 'the same direction that the world is going,' so we really don't know. In my case and in my thinking, music has mirrored the life we live in. You can see it backward. When you listen to Bach, it reflects the life and you can imagine it as it was at that time. When you listen to Beethoven, after the Third Symphony, you know that there is a revolution in Europe. It's in the music, too. But it was in literature and painting, and music was probably the third in order. When you listen to Debussy, you know that he has gone into the atelier of impressionistic painters and that he has read the poetry of the symbolists and impressionists. When one listens to music of Berg, you can imagine the life in Vienna and all the things that happened. When you listen to music of Kurt Weill, that was Berlin at that time. I think my music also mirrors what is happening today. A lot of music does. So we have the high-powered, twentieth century music and we also now have at the same time something very easy to listen to and things in between. We are so different as people and we are so different as composers. Diversity is today's trend and the music reflects that, too. There are so many good things in the world and we dispose of them too fast. Some things are left untouched. Some things are taken and others are not. That's in music, too. I'm sure there is beautiful music from many gifted people, but we are too many composers. We are too many performers. We are too many sports figures. The schools are turning out so many professional athletes as well as so many instrument players. How many can get to that top level? That's today's life.

BD: Do you feel that you are part of a lineage?

KH: Yes, I think so. In many ways I am a traditionalist.

Perhaps not in that exact term, but I have roots that came from the past.

Philosophically, I am the son of somebody, not only in life but also in

music. Somebody gave me the help and knowledge and I have taken it

from that person who was my musical father and have tried to do something

with it, and then pass it to others. That's how it goes.

KH: Yes, I think so. In many ways I am a traditionalist.

Perhaps not in that exact term, but I have roots that came from the past.

Philosophically, I am the son of somebody, not only in life but also in

music. Somebody gave me the help and knowledge and I have taken it

from that person who was my musical father and have tried to do something

with it, and then pass it to others. That's how it goes.

BD: You have worked with quarter-tones and polytonality. Are these things you have accepted and rejected, or have they filtered throughout your music?

KH: They have filtered throughout my music. I think we have very good ideas today and I accept new things. I'm not revolting against something new. On the contrary, I think there must be some potential good in new things. Composers don't want to write bad music and alienate the audiences. Even in revolutionary times, it's the necessity that the composer feels to do it. The avant guard is the faction that keeps us going on ahead. We would become senile if that didn't exist.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

KH: I am. I think that there are so many excellent musicians and many very good composers. Still I think that we have much more music today than we have ever had in the past. There may be too many concerts to which audiences don't come, but later everything will be sorted out. We will take what we need and what represents this period. The only music that will exist is that which is accepted first by performers and then by audiences.

BD: Slonimsky says your music, "has been oxygenated by humanistic romanticism." Is that accurate?

KH: If to express human feelings - joy, love - is romantic, then I am romantic. Expressing a fight for freedom must be romantic, too. I think that music can express these things and I don't want to be a cerebral composer. I want to be inventive, to have a score that will reveal something interesting and intriguing and sophisticated to the performer or conductor, or to another composer. At the same time, it must be musical and warm, and show that I care about other people.

BD: Is composing fun?

KH: At some moments, it's fun. When it gets closer to the deadline, then it can be frustrating. When you have time to think and prepare, it's fun. When it's the time to put things together, the composer is not different from the manager of the orchestra who has to produce all the press releases and meet people and make sure it's all done on time.

BD: Do you like meeting the public before or after concerts?

KH: I like to explain to audiences, when they ask me, what the composer is trying to achieve.

BD: Does that change from piece to piece, or are you trying to achieve something over a lifetime?

KH: It changes from piece to piece. But the audiences who are interested in the composer like to listen. Even if they don't agree with me, they like to accept an explanation from a composer. I like to say why I'm doing what I'm doing. People have the right to listen to it.

BD: Tell me about winning the Pulitzer Prize.

KH: The Pulitzer Prize is a very important prize, and the moment you receive it, it's like a zoom on one moment in your life. Then it remains, but it doesn't mean that the works either before or after are either worse or better. The members of the Fine Arts Quartet submitted my Third Quartet and didn't want to let me know - in case I didn't win.

BD: Does having the prize, then, focus too much attention on that piece?

KH: In my case, there seems to be more focus on Music for Prague. It's a curious thing because I like other things just as much. Apotheosis of this Earth, for instance, or Concerto for Orchestra. But it's Music for Prague that gets the attention.

BD: You're not sick of that one, are you?

KH: (laughing) No, no. There is enough narcissism left

to fight this!

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

= = = = = =

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

©Bruce Duffie

Linked from New Music Connoisseur

Magazine in December, 2001.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.