|

A native of Wolverhampton, England, Ian Hobson (born August 7, 1952) is recognized throughout the world for his masterful performances of the Romantic repertoire, his deft and idiomatic readings of neglected piano scores old and new, and his assured conducting from both the piano and the podium. Mr. Hobson is also renowned as a dedicated scholar and educator, who has pioneered renewed interest in the music of lesser-known masters Johann Hummel and Ignaz Moscheles. He is also an effective advocate of works written expressly for him by several of today’s noted composers, including John Gardner, Benjamin Lees, David Liptak, Alan Ridout, Roberto Sierra, and Yehudi Wyner.

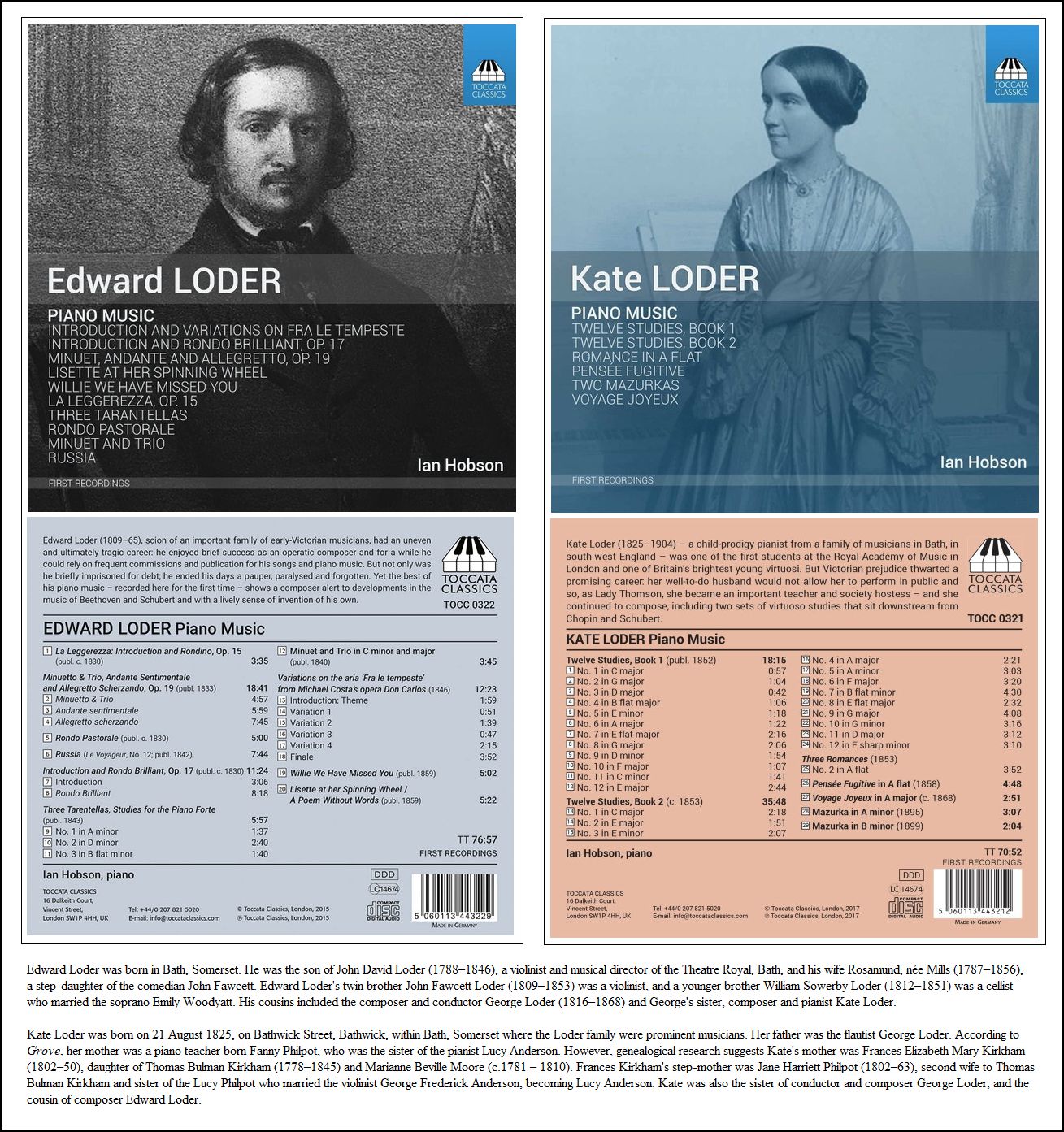

Active in the recording studio, Mr. Hobson has been engaged in recording

a 16-volume collection of the complete works of Chopin for the Zephyr label.

This edition includes approximately 45 minutes of Chopin music never before

recorded, making Mr. Hobson the first ever to record the composer’s entire

oeuvre as a single artist. Organized in chronological order, the pieces in

the collection were recorded between 2003 and 2009, mainly in Poland. Of

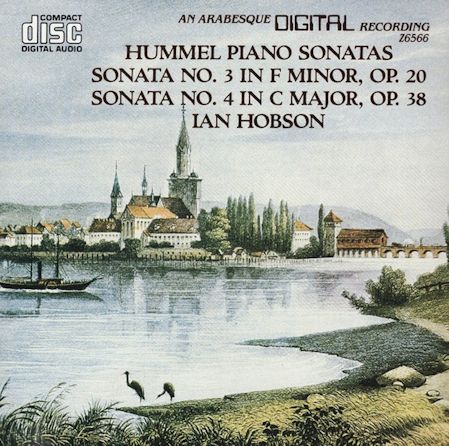

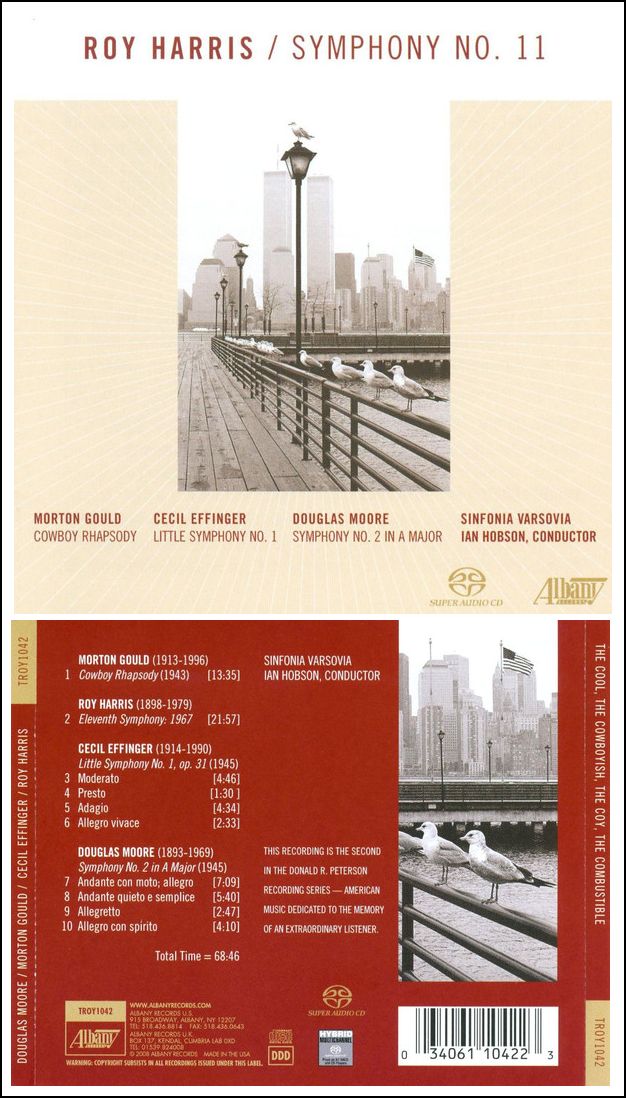

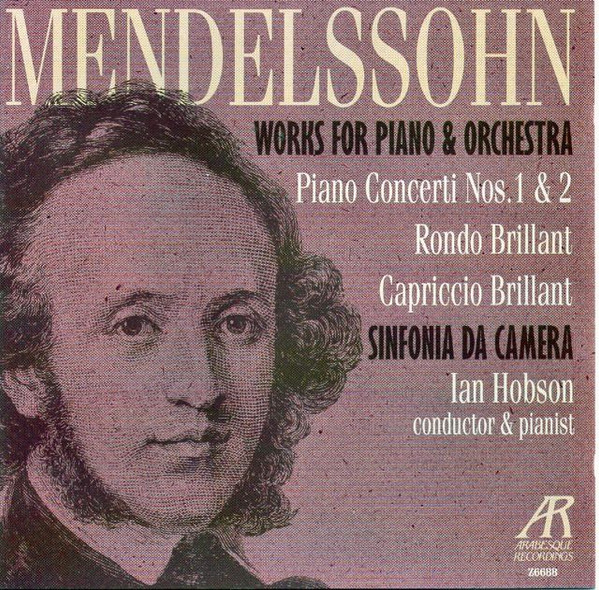

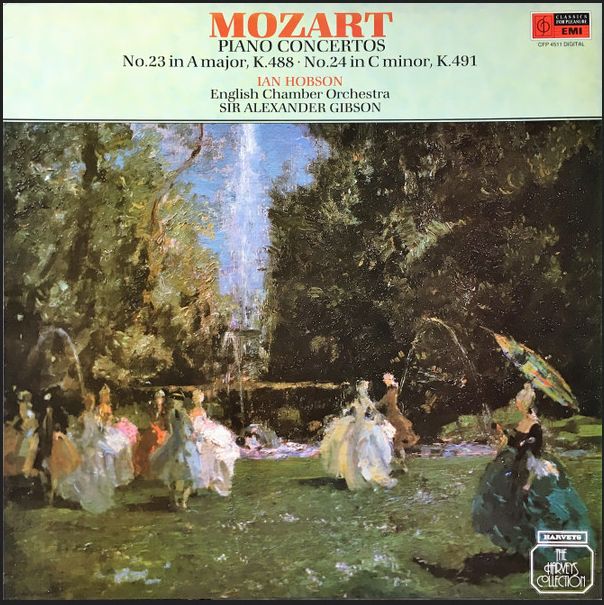

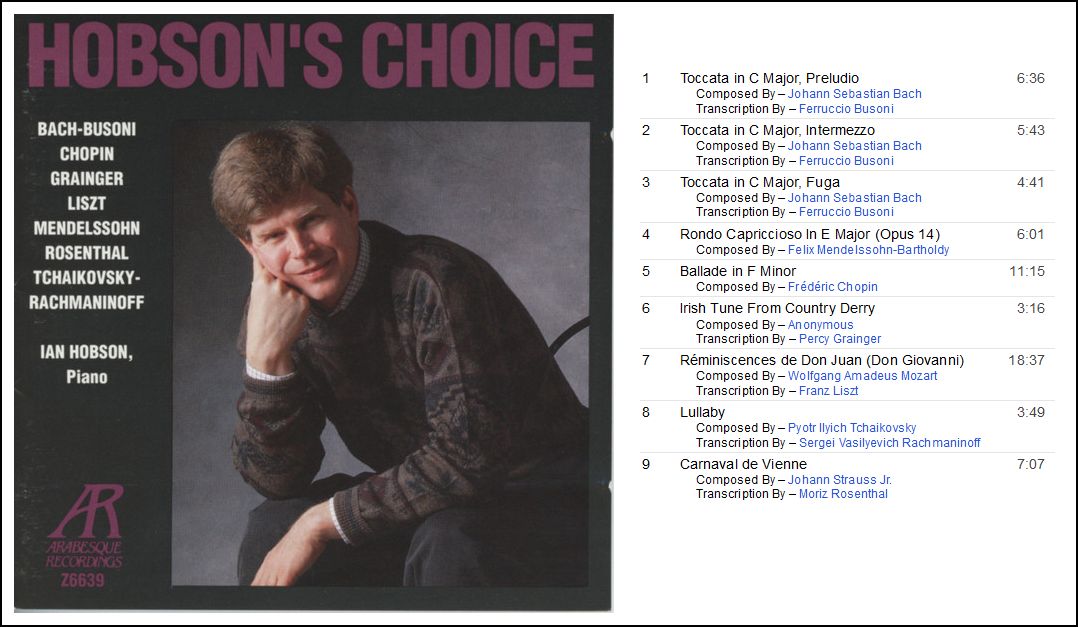

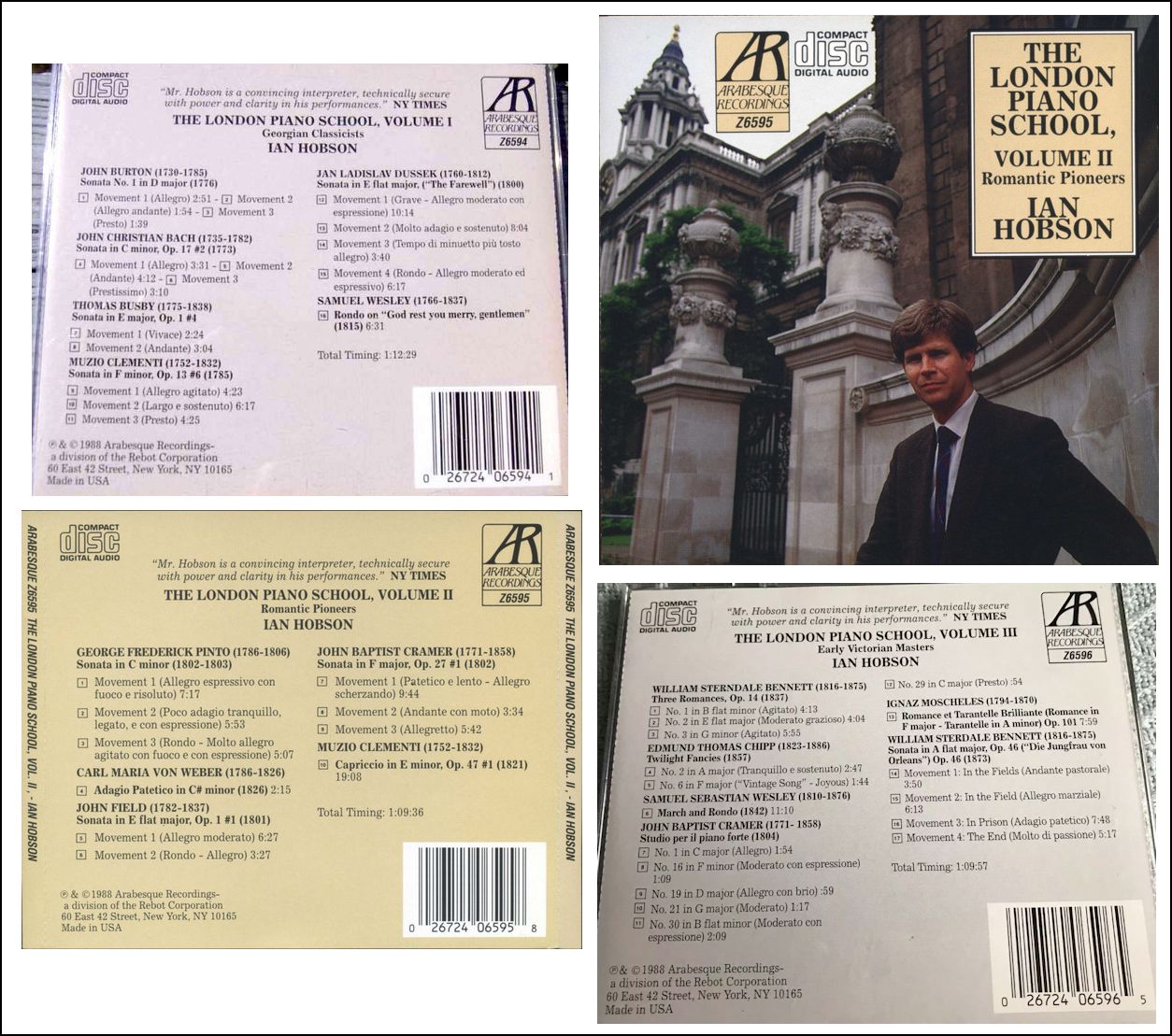

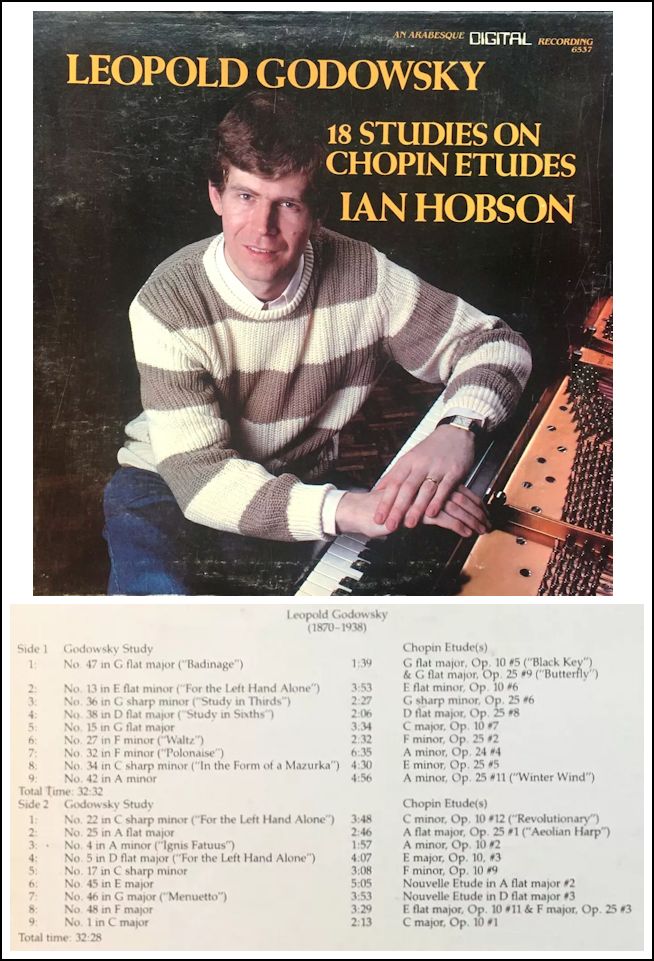

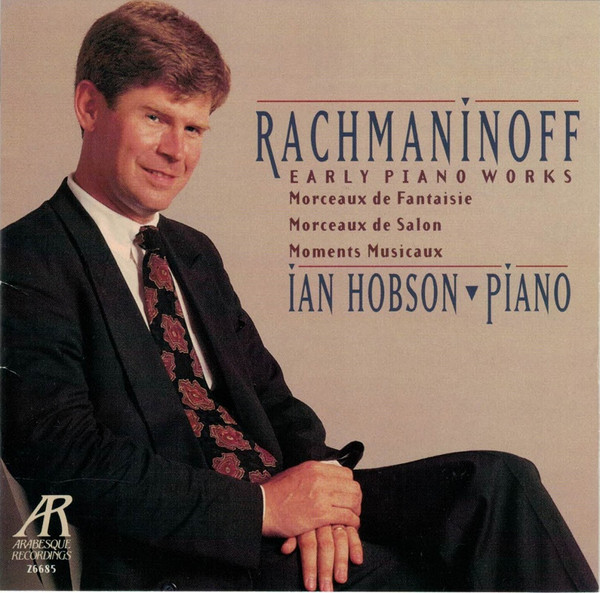

the 16 volumes, 12 are solo piano. [One CD of the set is shown at left.] Hobson presented a 10-recital series devoted to the 200th anniversary of the Romantic Era’s two greatest composers for the piano: Chopin and Schumann, at New York City’s Dicapo Opera Theatre. In the 2011-12 season Ian Hobson presented the complete solo piano works of Robert Schumann in Urbana, Illinois. Increasingly, Mr. Hobson is in demand as a conductor, particularly for performances in which he doubles as a pianist. He made his debut in this capacity in 1996 with the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra, and has subsequently appeared with the English Chamber Orchestra, Poland’s Sinfonia Varsovia (at Carnegie Hall) and Pomeranian Philharmonic and Kibbutz Chamber Orchestra of Israel, among others. Ian Hobson is also active as an opera conductor, with a repertoire that encompasses works by Cimarosa and Pergolesi, Mozart and Beethoven, and Johann and Richard Strauss. In 1997, he conducted John Philip Sousa’s comic opera, El Capitan, in a newly restored version with Sinfonia da Camera and a stellar cast of young singers. A fervent advocate of George Enescu’s music, he conducted and recorded the 2005 North American première of the operatic masterpiece, Oedipe, in a semi-staged version performed by Sinfonia da Camera on the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death. An artist of prodigious energy and resource, Mr. Hobson has amassed a discography of over 60 releases [a few of which are shown as illustrations on this webpage]. In the dual role of pianist/conductor, he and the Sinfonia Varsovia recorded for Zephyr Rachmaninoff’s four piano concerti and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini – a tour de force no other performer has matched. In addition, Ian Hobson is a much sought-after judge for national and international competitions, and has been a member of numerous juries, among them the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition (at the specific request of Mr. Cliburn), the Chopin Competition in Florida, Leeds International Pianoforte Competition (U.K.), Schumann International Competition (Germany) and Arthur Rubinstein Competition (Poland). In 2005, he served as Chairman of the Jury for the Cleveland International Piano Competition and New York City’s Kosciuzsko Competition; in 2008, he served in the same capacity for the New York Piano Competition – to which, renamed New York International Piano Competition, he returned in 2010. One of the youngest graduates in the history of London’s Royal Academy of Music, Ian Hobson subsequently pursued advanced studies at both Cambridge University and Yale University. He began his international career in 1981 when he won First Prize at the Leeds International Piano Competition, after having earned silver medals at both the Arthur Rubinstein and Vienna-Beethoven competitions. Among his distinguished teachers were Sidney Harrison, Ward Davenny, Claude Frank and Menahem Pressler, while, as a conductor, he studied with Otto Werner Mueller, Dennis Russell Davies, Daniel Lewis and Gustav Meier, and worked with Lorin Maazel in Cleveland and Leonard Bernstein at Tanglewood. Mr. Hobson is Emeritus Center for Advanced Study and Swanlund Professor of Music at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and a Visiting Fellow at Magdalene College, Cambridge. He received his diploma from the Royal Academy of Music, a BA from Cambridge, an MM. (piano, organ, and harpsichord), and a DMA (piano and conducting), Yale School of Music.== Biography from the website of the University

of Illinois Urbana-Champaign [with slight additions]

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 24, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993 and 1997, and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2005, 2006, and 2012. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.