Soprano Constance Hauman, a native of Toledo, Ohio, studied music and political science at Northwestern University and is an alumna of the Interlochen Center for the Arts.

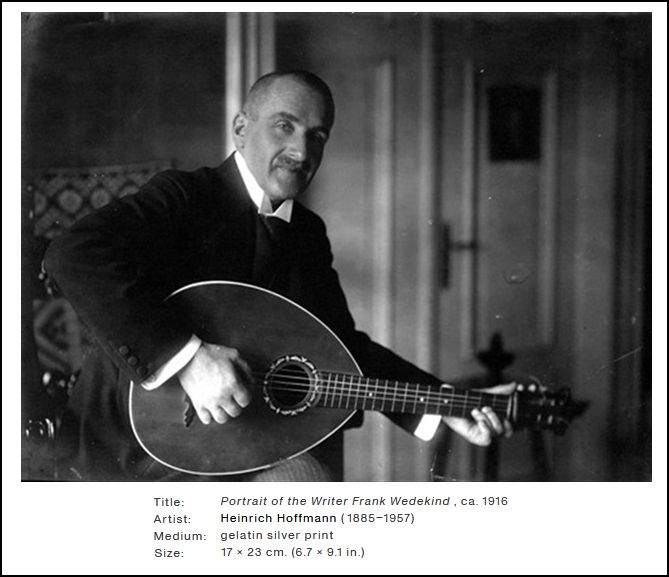

In 1986, she sang Ariel in the Des Moines world premiere of Lee Hoiby’s opera The Tempest, and ten years later she repeated the role in her Dallas Opera debut. In 1989, she came to international prominence as Cunegonde in Bernstein’s Candide, in a complete concert performance with the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the composer at the Barbican Centre.

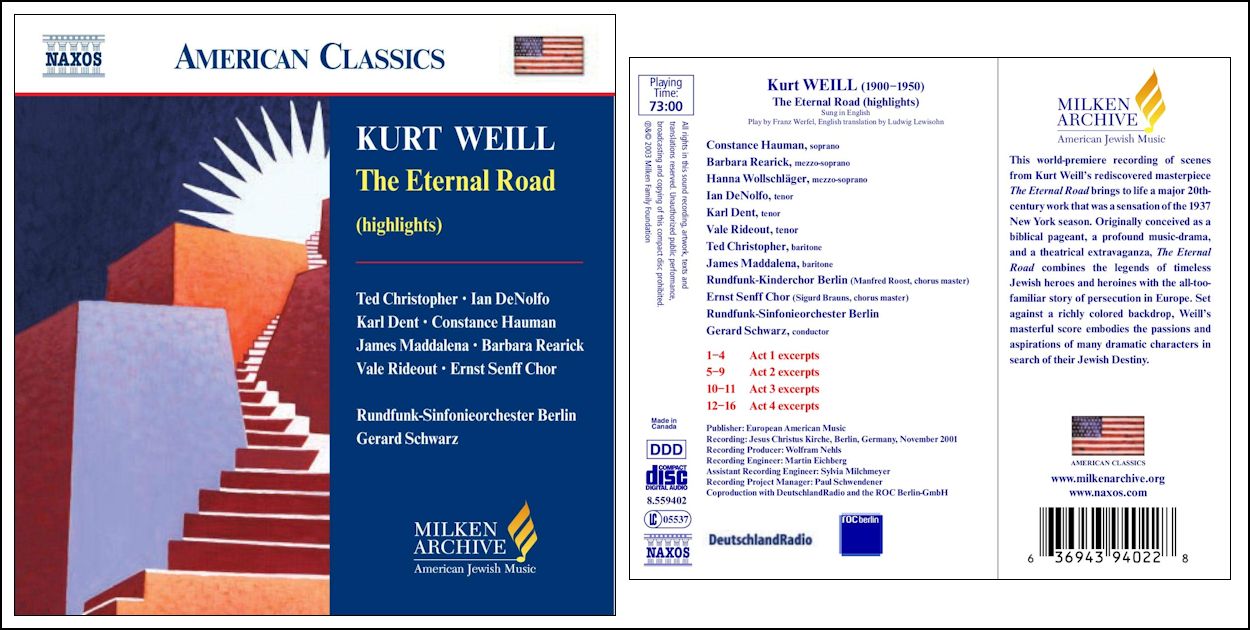

In 1990, she made her New York debut singing “Glitter and Be Gay” at a Bernstein memorial tribute. She has given recitals in Los Angeles and New York of songs by refugee composers from Nazi Germany and Austria and has appeared in a program entitled Kurt Weill’s Berlin.

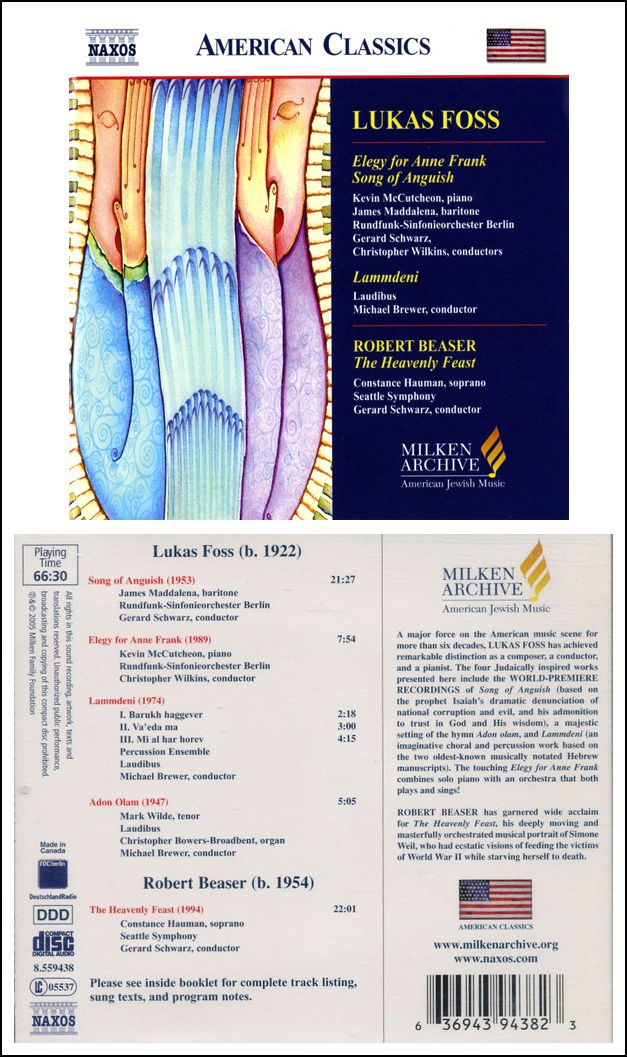

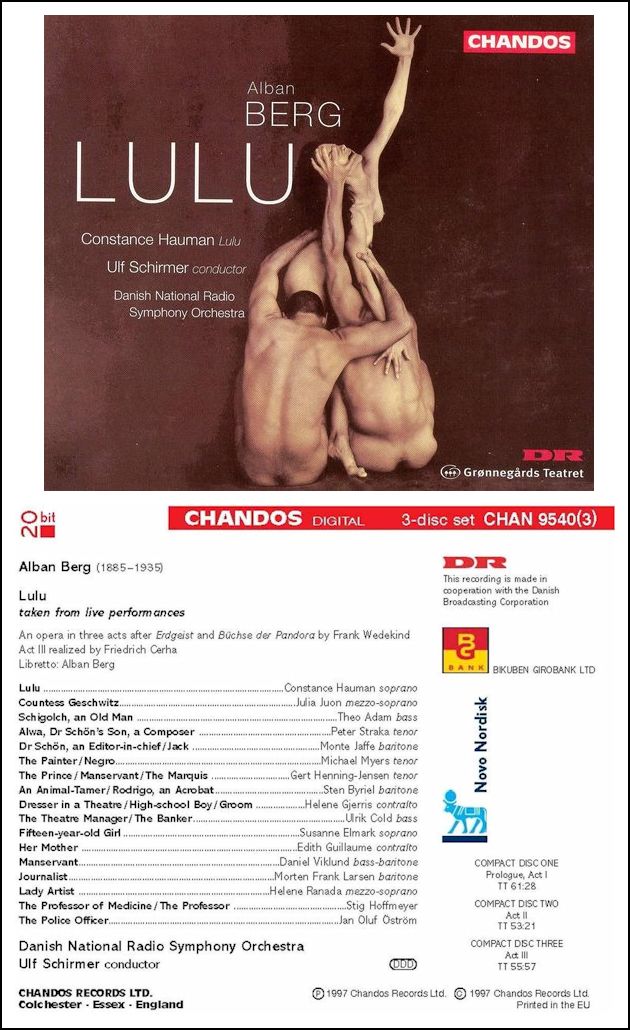

She has appeared and recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic, Chicago Lyric Opera; Chicago Symphony; San Francisco Symphony; London Symphony; New York City Opera, Los Angeles Opera, Long Beach Opera, Pittsburgh Opera, Dallas Opera, Washington National Opera, Michigan Opera Theater, Miami Opera, Toledo Opera, Spoleto Festival Charleston S.C.; Canadian Opera; English National Opera, Welsh National Opera, London Sinfonietta; Opéra de Nice, Opéra de Marseille, Opéra de Tours, Opéra de Nantes, Opéra de St-Étienne, Opéra du Rhin, Opéra de Montpellier, Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Opéra Comique, Opéra National de Paris; Opera de Roma, Teatro Communale Florence; Spoleto Festival; Spanga Festival Holland; Japan Philharmonic; Royal Danish Radio Orchestra; Hong Kong Festival; Orquesta di Lisboa, Portugal; VARA Radio Orchestra, Amsterdam.

Hauman is a Richard Tucker Award winner, and a 2008 recipient of an Alumni Merit Award from Northwestern University.