|

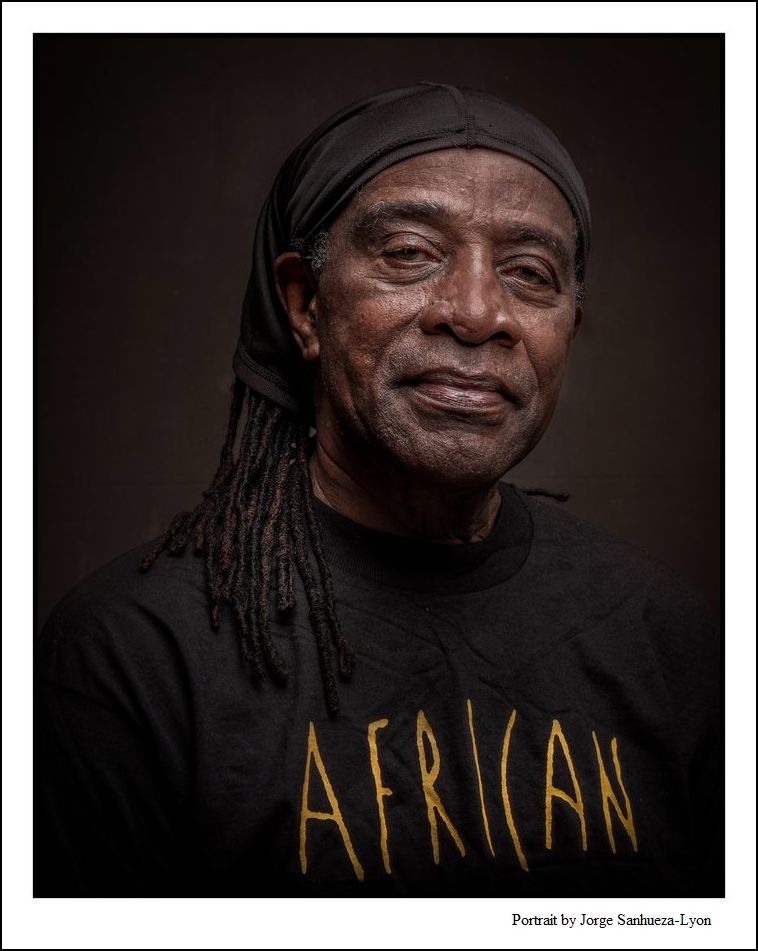

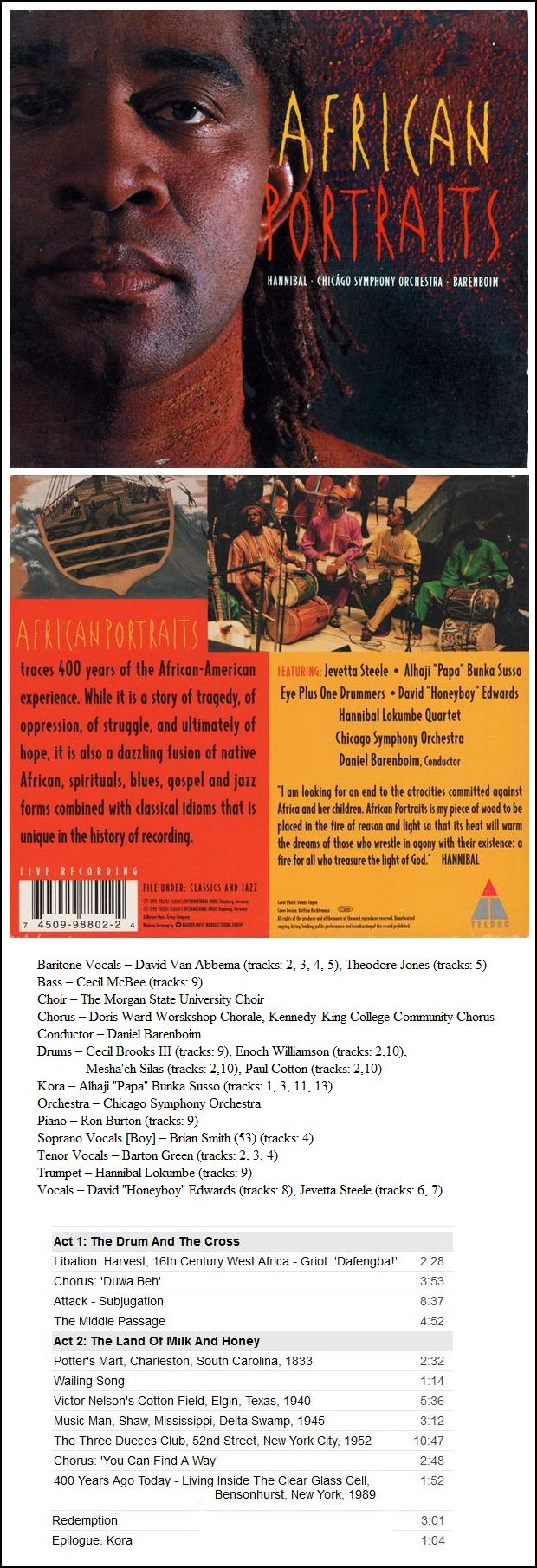

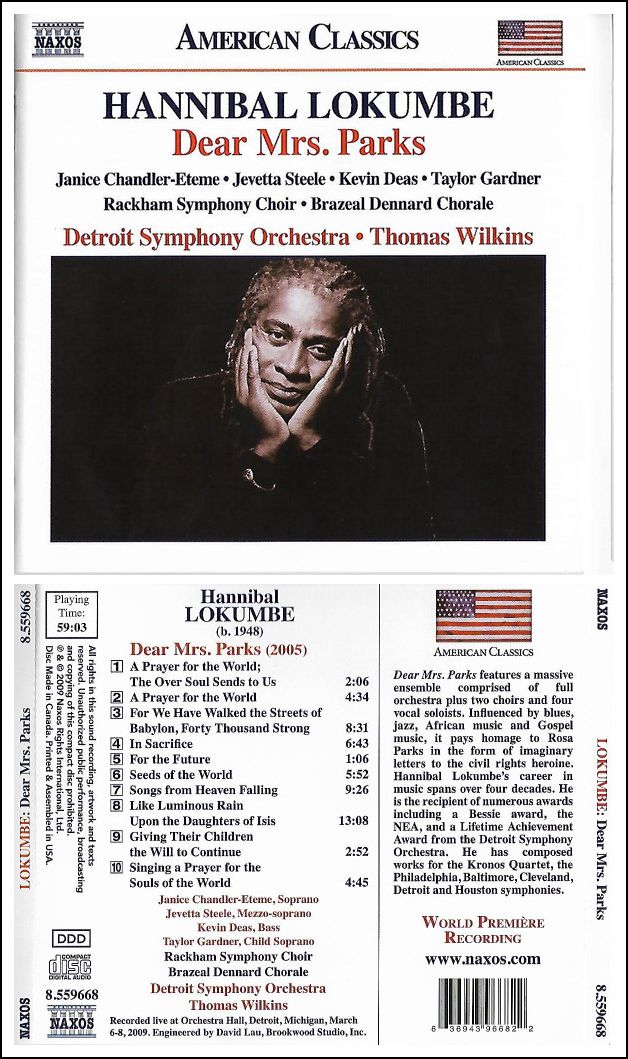

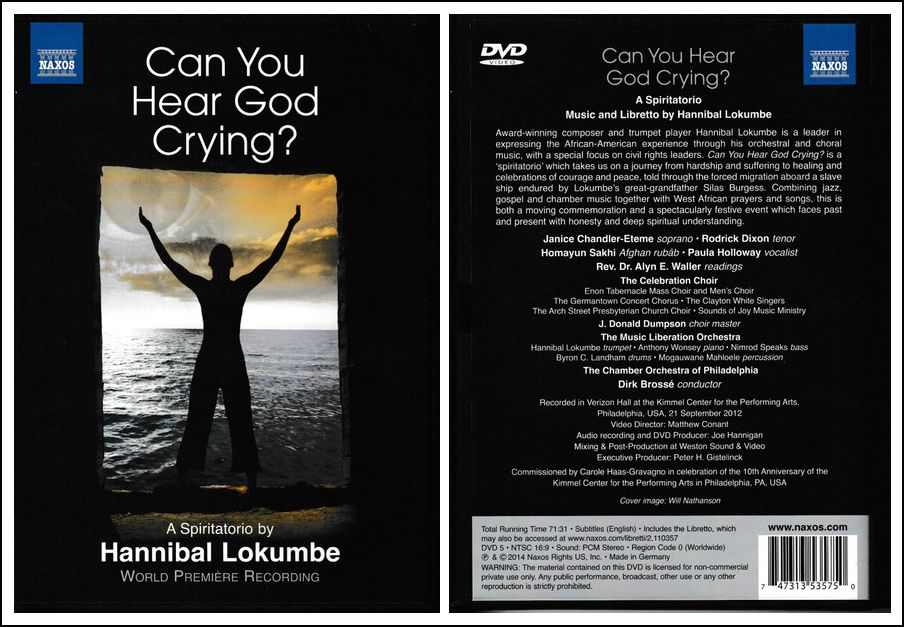

The journey of composer Hannibal Lokumbe, trumpeter of the Music Liberation Orchestra, has taken him from the cotton fields of Elgin, Texas, where he was first inspired by the spirituals and hymns of his grandparents, to the stages of Carnegie Hall and much of the world. He spent twenty-five years in New York City playing trumpet and recording with some of his jazz heroes (including Gil Evans, Pharaoh Sanders, Roy Haynes, Elvin Jones, and McCoy Tyner) and is the recipient of numerous awards including The USA Artists (Cummings Fellow), The Joyce, Bessieʼs, NEA, and Lifetime Achievement Award from the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Lokumbe is a leader in expressing the African-American experience through orchestral and choral music, with a particular focus on civil rights leaders. In 1998, the New Jersey Symphony commissioned and premièred God, Mississippi and a Man Called Evers about the slain civil rights activist Medgar Evers. Other works include Soul Brother, inspired by the life of Malcolm X, and A Great and Shining Light, about former Atlanta mayor and United Nations Ambassador Andrew Young. He has composed works for Carnegie Hall, The Kronos String Quartet, as well as the Philadelphia, Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit and Houston Symphonies. His groundbreaking African Portraits was performed and recorded by the Chicago Symphony under the direction of Daniel Barenboim and has been performed numerous times since its November 11, 1990 Carnegie Hall début. In addition, Dear Mrs. Parks, which pays homage to Rosa Parks in the form of imaginary letters to the civil rights heroine, was commissioned, performed and recorded by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra in March 2009 and released by Naxos [8.559668]. He recently played the rôle of Luke in a major production of James Baldwinʼs play The Amen Corner at The Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, MN.== Biography (above) is from the Naxos website.

The material (below) is from other sources.

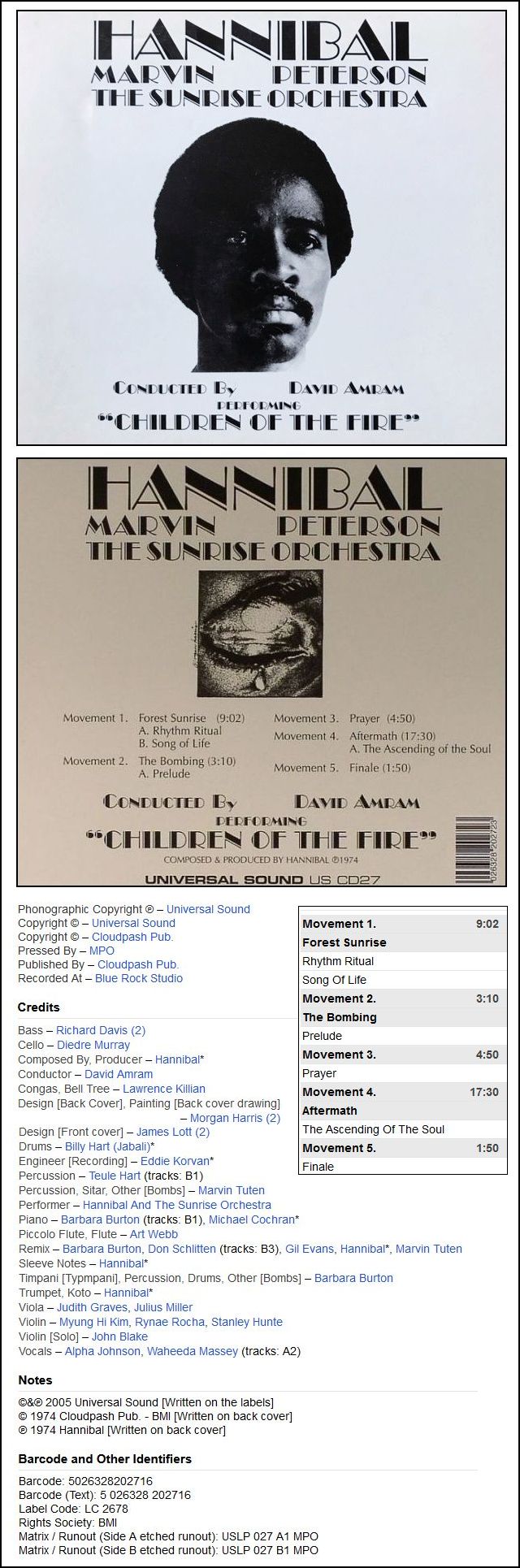

Hannibal Lokumbe (born Marvin Peterson on November 11, 1948) grew up on a farm, and initially received his musical education through his mother (an organist) which he deepened at high school. He first played drums and performed with his own group beginning in 1961, the Soulmasters, who went on tour between 1965 and 1967 (also with T-Bone Walker). He studied at North Texas State University from 1967 to 1969, and moved to New York City from 1967 to 1969. He played with Frank Foster, Eric Kloss, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Roy Haynes, Elvin Jones, Archie Shepp, Clifford Brown, Sam Rivers and Gil Evans on his album Svengali. In 1973, Peterson performed the first part of his suite "Children of the Fire" as part of the Newport Jazz Festival. In 1974, he played following his performance with the band of Gil Evans at the Montreux Jazz Festival and at the New Jazz Meeting Baden-Baden. In the following years he was repeatedly present in Europe with his own Sunrise Orchestra, and was also on tour with George Adams and John Scofield. He performed the suite "The Angels of Atlanta" with a gospel choir, which he dedicated to the victims of a mass murderer. He also participated in productions by Don Pullen, Kip Hanrahan, Andrew Cyrille, Billy Hart, Bardo Henning, Johannes Barthelmes and Richard Davis' New York Unit. In 1992/93 he composed for the Kronos Quartet. In 1995, he performed his large-scale third-stream oratorio "African Portraits" with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Daniel Barenboim. In recent years he has lived in New Orleans, where he created portraits of African Americans in the series "And Their Voices Cry Freedom" at the Contemporary Arts Center. Written in 2005, soloists, choirs, the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and conductor Thomas Wilkins gave his oratorio Dear Mrs. Parks about the American civil rights activist Rosa Parks. This was followed in 2019 by his oratorio Healing Tones with a choir, soloists and the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin. |

Kahlil G. Gibran (`ka-lil jə-ˈbrän) (November 29, 1922 –

April 13, 2008), sometimes known as "Kahlil George Gibran" (note the artist's

preferred Americanized spelling of his first name), was a Lebanese American

painter and sculptor from Boston, Massachusetts. A student of the painter

Karl Zerbe at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gibran first

received acclaim as a magic realist painter in the late 1940s when he

exhibited with other emerging artists later known as the "Boston Expressionists".

Called a "master of materials", as both artist and restorer, Gibran turned

to sculpture in the mid-fifties. In 1972, in an effort to separate his

identity from his famous relative and namesake, the author of The Prophet,

Gibran Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931), who was cousin both to his father Nicholas

Gibran and his mother Rose Gibran, the sculptor co-authored with his wife

Jean a biography of the poet entitled Kahlil Gibran His Life And World.

Gibran is known for multiple skills, including painting; wood, wax, and

stone carving; welding; and instrument making.

Kahlil G. Gibran (`ka-lil jə-ˈbrän) (November 29, 1922 –

April 13, 2008), sometimes known as "Kahlil George Gibran" (note the artist's

preferred Americanized spelling of his first name), was a Lebanese American

painter and sculptor from Boston, Massachusetts. A student of the painter

Karl Zerbe at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gibran first

received acclaim as a magic realist painter in the late 1940s when he

exhibited with other emerging artists later known as the "Boston Expressionists".

Called a "master of materials", as both artist and restorer, Gibran turned

to sculpture in the mid-fifties. In 1972, in an effort to separate his

identity from his famous relative and namesake, the author of The Prophet,

Gibran Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931), who was cousin both to his father Nicholas

Gibran and his mother Rose Gibran, the sculptor co-authored with his wife

Jean a biography of the poet entitled Kahlil Gibran His Life And World.

Gibran is known for multiple skills, including painting; wood, wax, and

stone carving; welding; and instrument making. [There is, of course, much more about Gibran and

his artistic achievements,

but since this website is devoted to music, here is some information related to that topic. BD] Throughout the 1940s, Gibran's friendship with Hyman Bloom was, in part, due to their mutual devotion to the music of what was then called “the Orient". The young Gibran had always searched for recordings of early 20th century Arabic singers and instrumentalists, and soon joined a group of devotees of Middle Eastern and Indian music that included Bloom, composer Alan Hovhaness, painter Hermon Di Giovanno, sculptors Frank and Jean Teddy Tock, Dr. Betty Gregory, and, later on, James Rubin, founder of Boston's Pan Orient Arts Foundation. As Gibran's reputation for building instruments grew, he also repaired

instruments for players from local nightclubs, as well as creating and

restoring instruments for the Museum of Fine Arts [Boston] and folk musicians.

A self-taught luthier, he began constructing ouds, sazes, Renaissance-type

lutes, and even bows. His vihuela, a 15th-16th century Spanish forerunner

of today's guitar, was admired and played by many classical guitarists,

and featured in a 1954 concert Court Music Of The Spanish Renaissance

at the Museum of Fine Arts. Throughout his life, he continued to indulge

his passion for building violins as well as other exotic instruments. In

the early 1990s he took time to self-publish his deeply researched theory

illuminating the mystery of the brilliant tonal quality of Stradivarius and

other Cremonese fiddle-makers. Observations On The Reasons For The

Cremona Tone appeared in the January 1994 bulletin of the Southern California

Violin Makers, with the convincing and tested argument that burnishing

the wood face of instruments prior to varnishing created a compressed,

non-spongy, and more resonant soundboard, and consequent tonal brilliance

and richness.

Pochette in its case. |

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 28, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following February. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.