Two conversations with Bruce Duffie

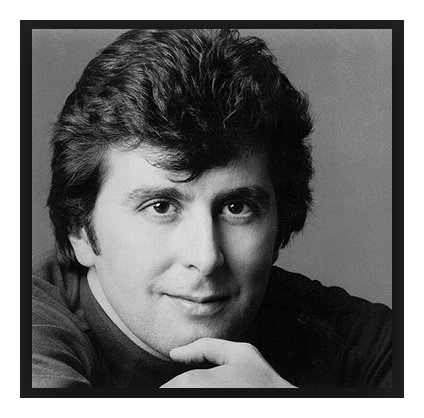

Jerry Hadley

US tenor whose great vocal facility

equipped him for both operas and musicals

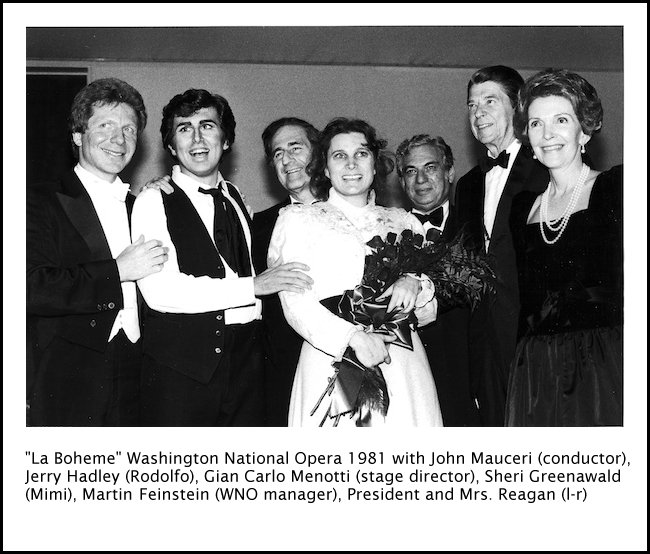

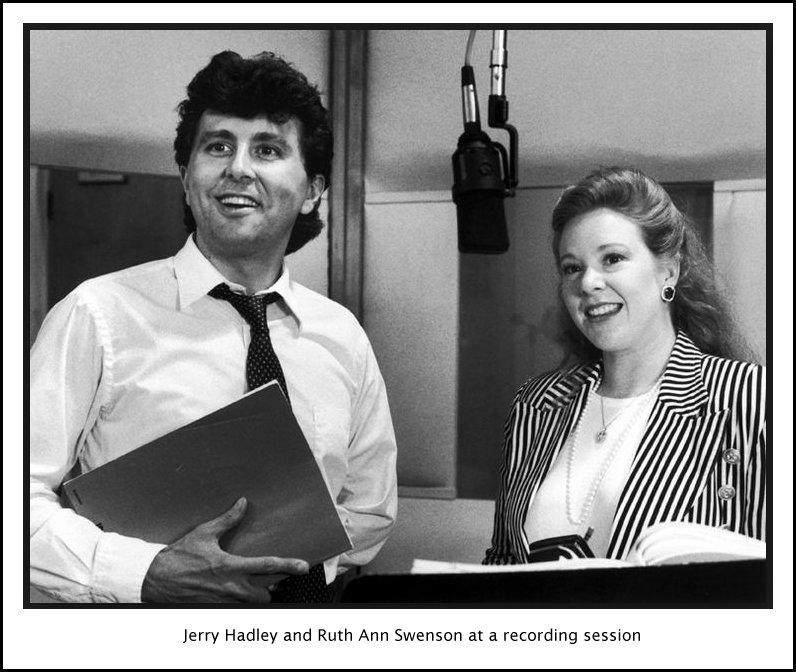

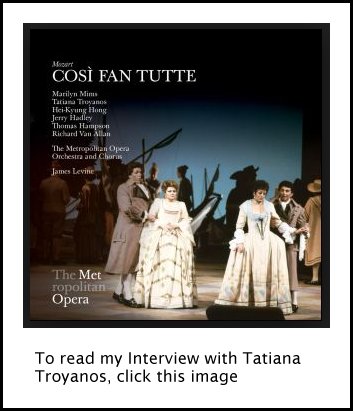

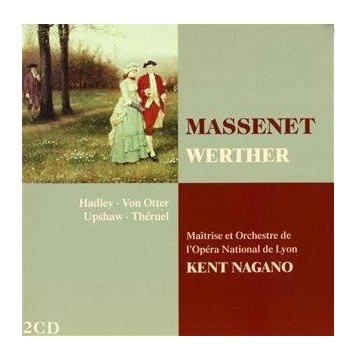

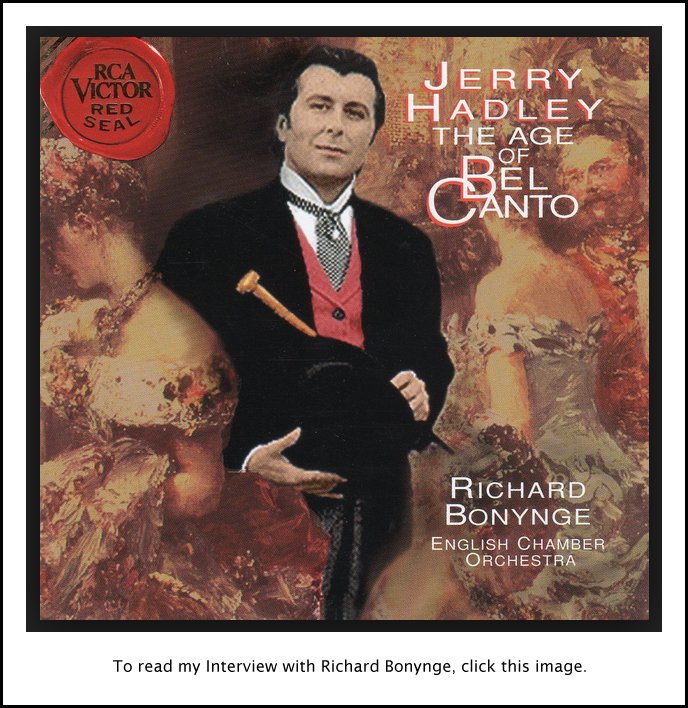

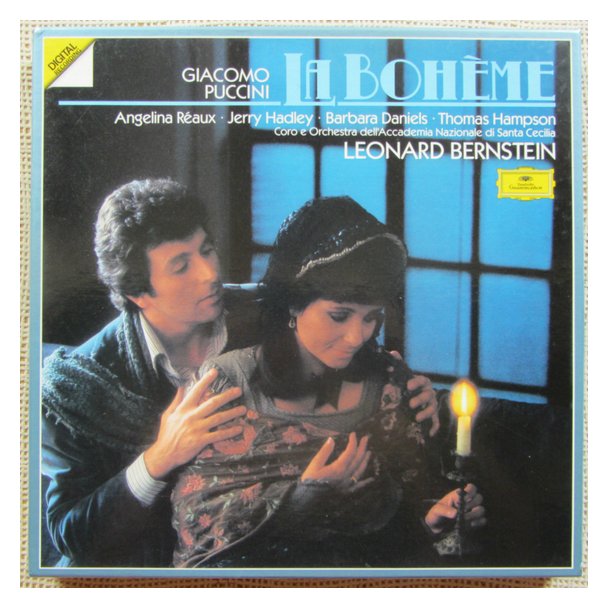

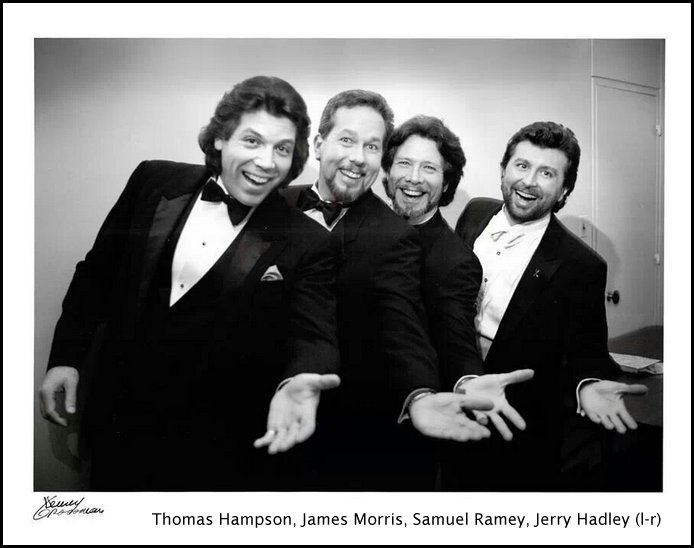

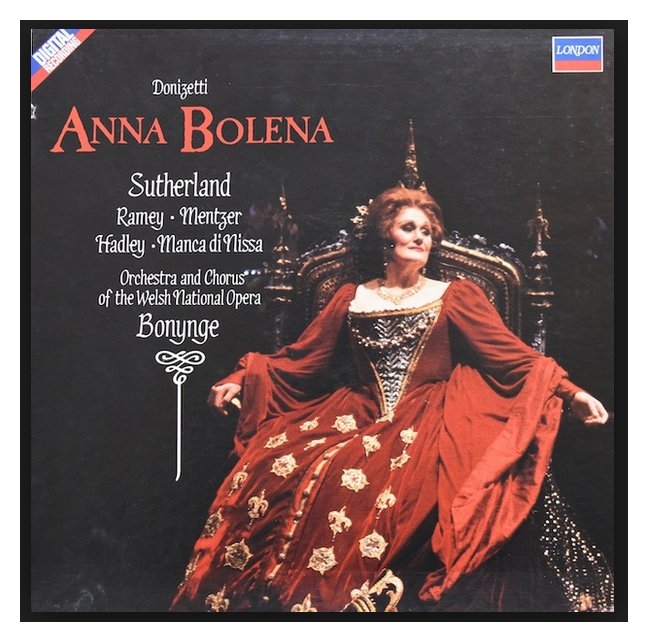

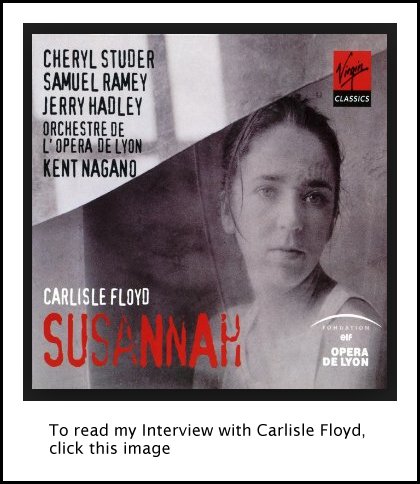

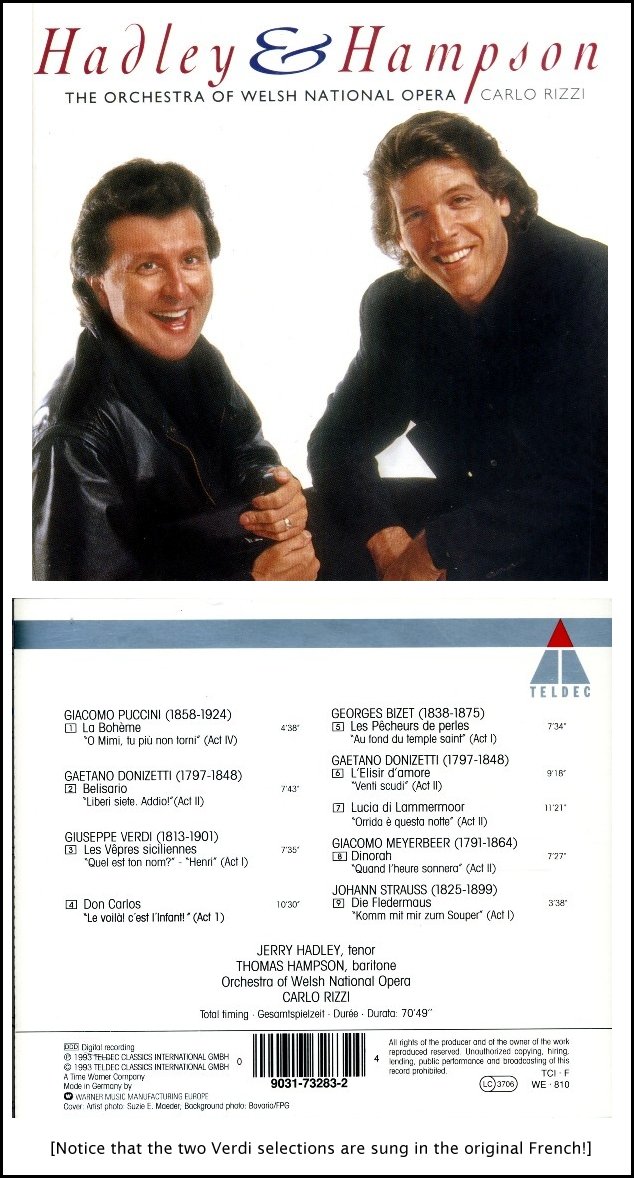

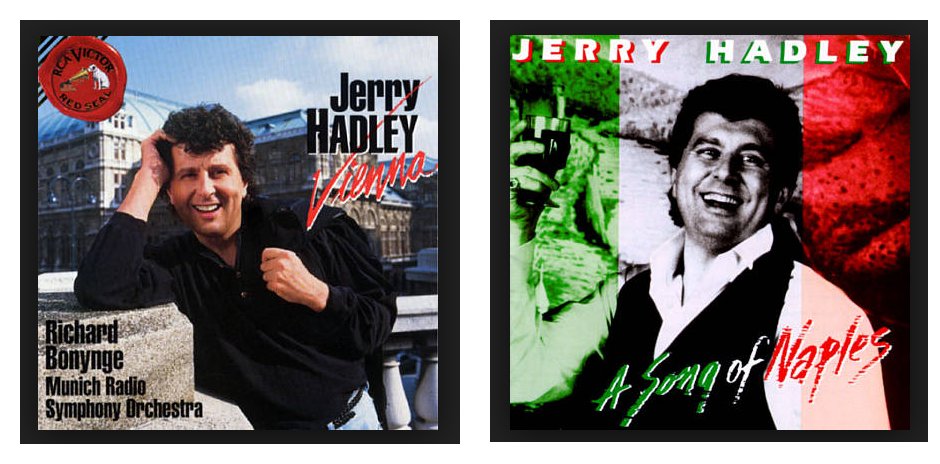

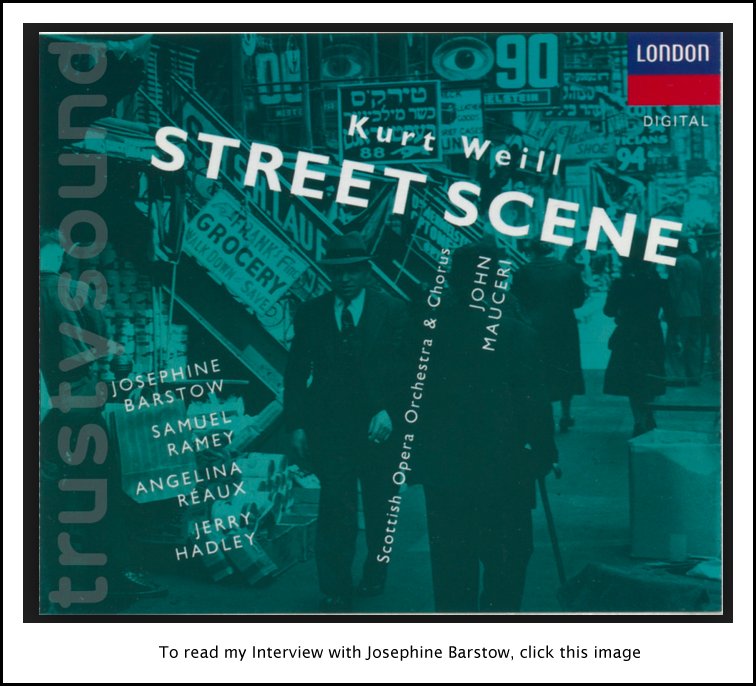

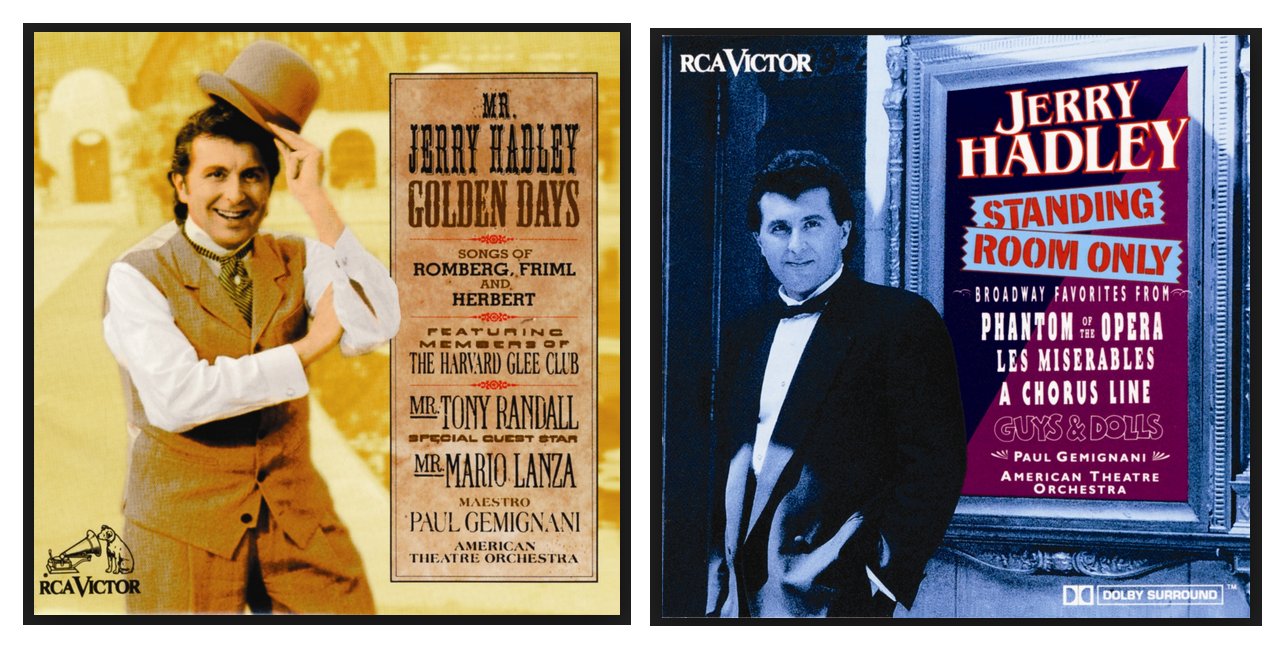

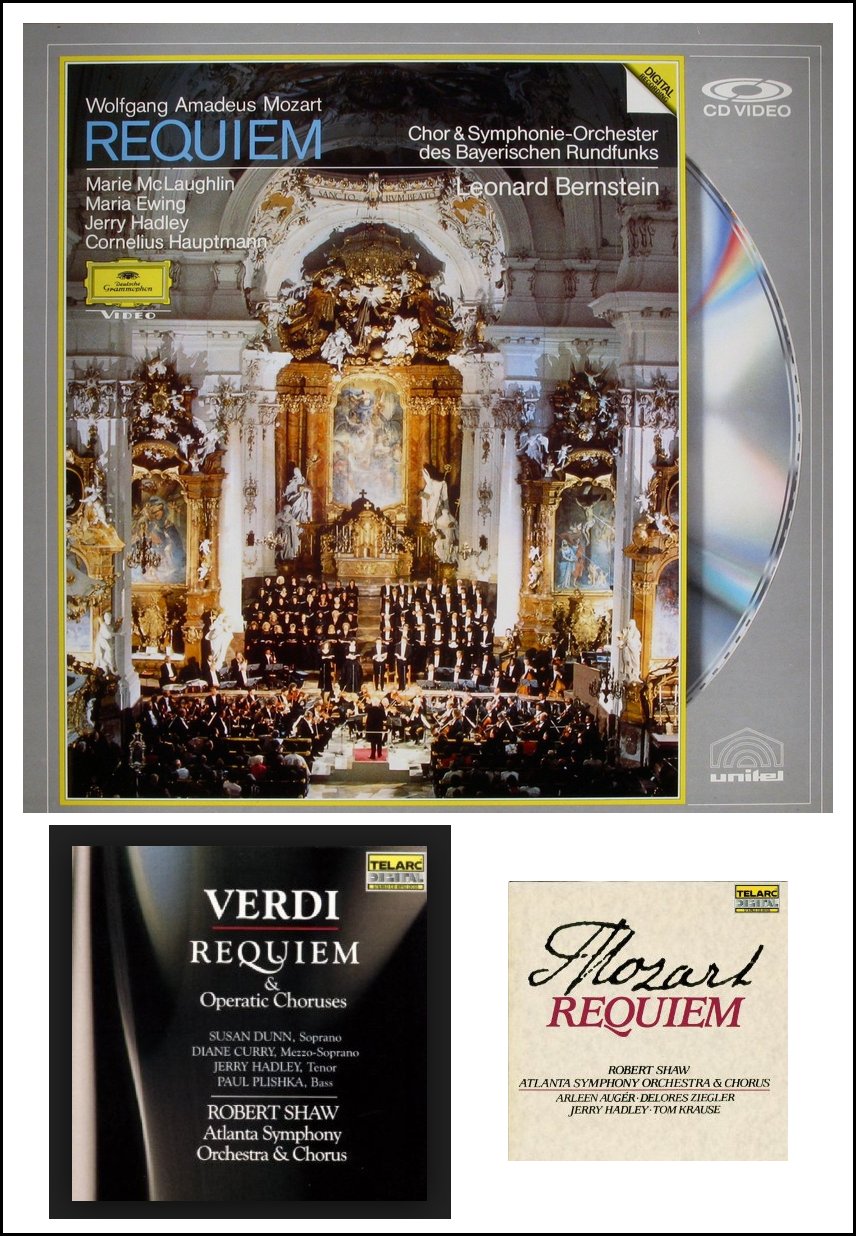

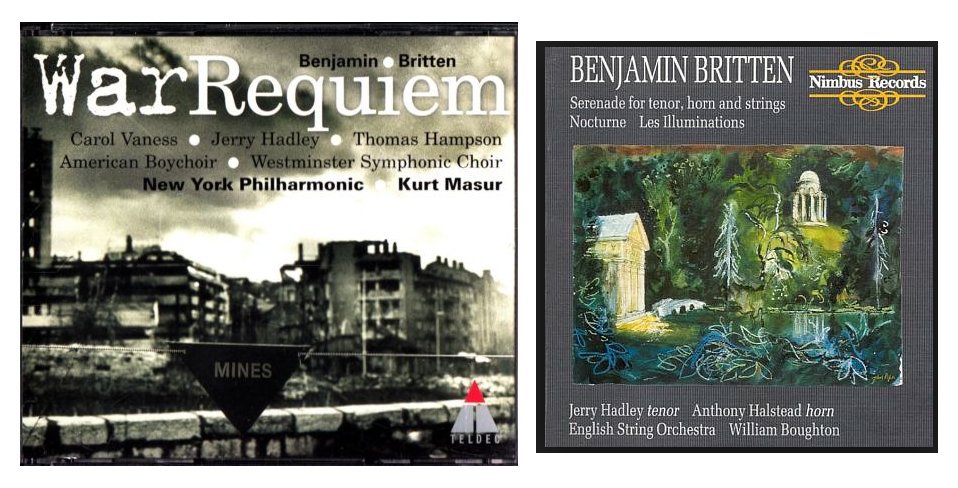

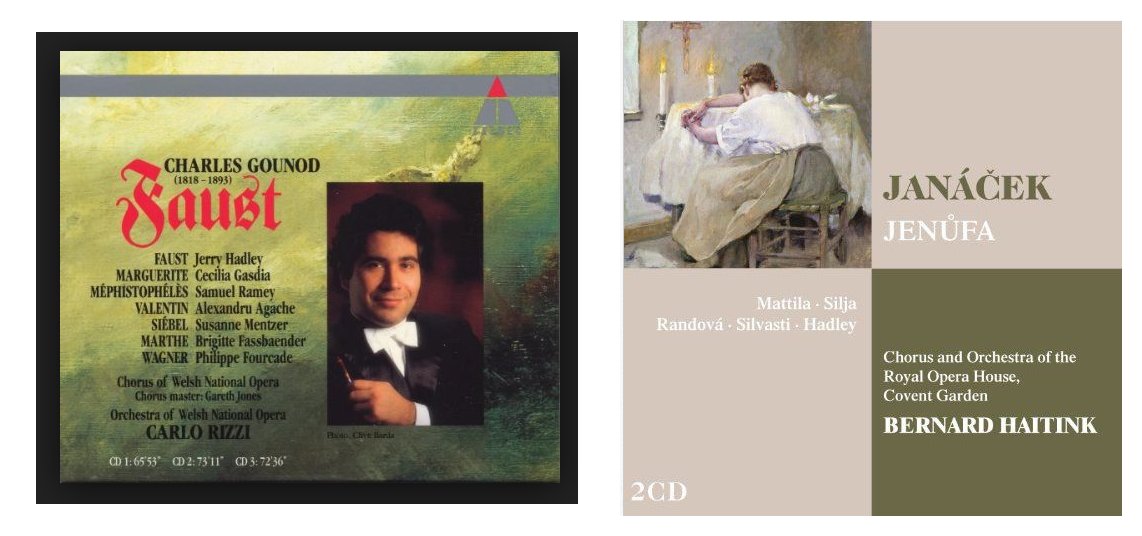

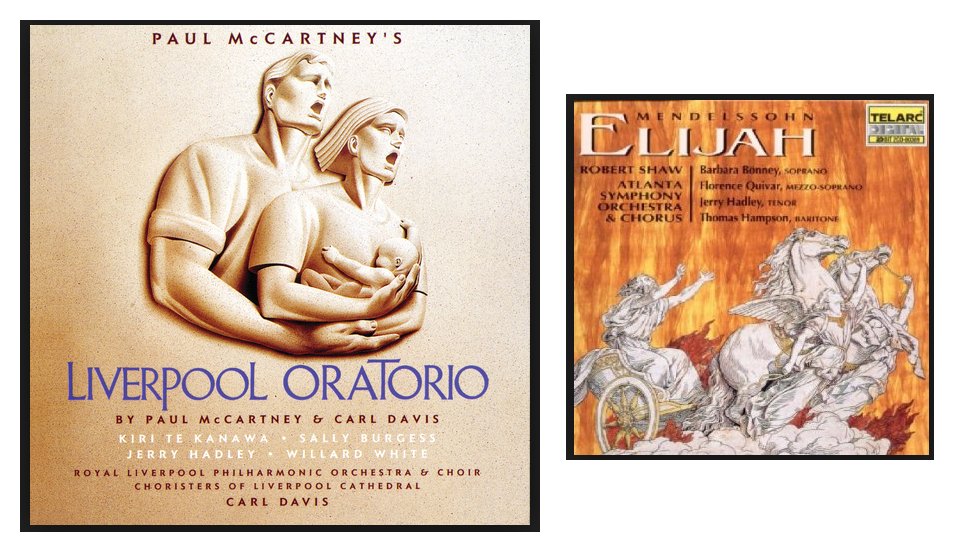

By Patrick Stearns, The Guardian July 18, 2007 [Text only - photos from other sources] Jerry Hadley, the fresh-faced tenor from the Illinois heartland, has died from an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound to his head at the age of 55, following treatment for depression. The incident occurred on July 10; he was taken off life support on July 16. For decades, he was a dependable lyric tenor presence in the world's great opera houses and music festivals with a particular facility for singing modern music with an Italianate lyricism, starting with his signature role, Tom Rakewell in Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress in a student production at the University of Illinois. With no change in technique, his clean vocal production also encompassed Broadway musical theatre. In Hadley's best years, he was the ebullient, un-neurotic concert partner of baritone Thomas Hampson in what were playfully named the "Tom and Jerry" concerts. Hadley was married with two sons in affluent Wilton, Connecticut, and had a thriving recording career, including numerous complete opera recordings as well as highly publicised crossover albums in the 1990s for RCA. Both Beverly Sills (obituary, July 4) and Joan Sutherland played significant roles in his early career, the former offering him his first big opera house contract with the New York City Opera in 1978, the latter casting him in his first full opera recording, Donizetti's Anna Bolena, in the mid-1980s. The news of his death was, to say the least, a shock. One anonymous blogger from Boston spoke for many: "I saw Jerry Hadley [in a] master class earlier this year that rejuvenated my love of singing and brought many singers in the class to greater depths of emotional connection to their performances. I count it as a turning point in my own studies, and I cannot square that delighted, energetic man with the same person who wanted to die." However, with last year's arrest for drink-driving (the charges were dropped because, while he had been drinking, he was not driving when apprehended), a different picture began to emerge. His voice had been less reliable and lustrous. Though a frequent presence at the Metropolitan Opera starting in 1987, he had not sung there since 2002, when he gave a performance of the John Harbison opera, The Great Gatsby. The RCA crossover discs had never made much of an impact, either with critics or on the sales charts. In recent years, Hadley was divorced from his wife and singing mostly pops concerts, though a Madam Butterfly earlier this year in Australia apparently gave him new confidence on his operatic prowess. Though he was reportedly discussing new roles such as Mime in Wagner's Ring cycle, he was also considering bankruptcy. Such circumstances among world-class singers are infrequent, but hardly unheard of in a world where vocal health - not financial acumen - is a paramount consideration. Hadley always seemed to be the exception to that. Born in Princeton, Illinois, and brought up on a farm, he discovered his talent for opera while attending Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois, before he had even seen one staged professionally. Vocal rest, he once said, came second to family duties. Though he lost his voice for months in the late 1980s - and said he learned a greater appreciation for life beyond his career - he came back, singing as effortlessly as ever. Indeed, what floored critics about the young - and even middle-aged - Hadley was his ease. Passages in The Rake's Progress that caused struggle with most tenors did not for him. Why, he could not say. The music's odd intervals simply never gave him trouble. As Alfred in Johann Strauss II's Die Fledermaus, he playfully tossed off bits of the most troublesome tenor arias. During his New York City Opera years (1979-89), he learned new roles quickly - the title role of Massenet's Werther, among them - and in a special, all-star concert version of Richard Strauss's Capriccio at Carnegie Hall, sang the role of Flamand. Unlike many opera singers who lost credibility in singing Broadway scores, Hadley's prestige only increased - at first - with his celebrated recording of Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II's Show Boat with Teresa Stratas. He was a favourite of Leonard Bernstein, who is said to have offered him the leading tenor role in his 1984 recording of West Side Story, which Hadley turned down. However, Hadley was featured in Bernstein recordings of the Mozart Requiem, Puccini's La Bohème and Bernstein's own Candide. At Bernstein's memorial at Carnegie Hall, Hadley moving sang It Must Be So from that score. As Hadley grew more confident on stage, however, critics identified a lack of artistic taste that grew more pronounced in later years. He was featured vocalist in the RCA recording Symphonic Music of the Rolling Stones, specifically singing Sympathy for the Devil in operatic voice. The disc was one of the label's biggest failures. Nor did his appearance in Paul McCartney's Liverpool Oratorio, portraying a blue-collar worker shouting for his dinner, help his artistic standing. At Cecilia Bartoli's 1996 Metropolitan Opera debut in Mozart's Così Fan Tutte, Hadley sang Ferrando with extravagant ornamentation that left some critics baffled. None the less, he continued to be featured in prestige projects, such as the 1996 Peter Mussbach production of The Rake's Progress in Salzburg and the 2002 recording of Janáček's Jenůfa at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden. Even with a self-imposed conclusion to his career, Hadley had what many tenors long for - nearly 30 years of almost unbroken activity, spread over both the US and Europe, in a nearly unprecedented range of composers, from Mozart to McCartney. · Jerry Hadley, tenor, born June 16 1952; died July 18 2007 -- Names which are links refer

to my Interviews elsewhere my this website. BD

|

|

Jerry

Hadley at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1986-87 - La Bohème (Rodolfo) with Esperian, Wroblewski, Putnam, Washington, Kreider, Capecchi; Mauceri, Copley, Pizzi Merry Widow (Camille) with Ewing, Titus, Adams, Kaasch, Negrini; Podič, Mansouri, Laufer, Tallchief 1987-88 - Così fan tutte (Ferrando) with Te Kanawa, Howells, McLaughlin, Titus, Nolen; Pritchard, Ponnelle 1988-89 Traviata (Alfredo) with Tomowa-Sintow, Pons; Bartoletti, Chazalettes, Pizzi, Tallchief Falstaff (Fenton) with Wixell, Daniels, Corbelli, Walker, Swenson, Horne, Andreolli; Conlon, Ponnelle 1990-91 - Magic Flute (Tamino) with Mattila, Nolen, Jo, Lloyd, Stewart; Kuhn, Everding, Zimmermann 1991-92 - L'elisir d'amore (Nemorino) with Gasdia, Corbelli, Desderi, Futural; Pappano, Chazalettes, Santicchi 1992-93 - Pelléas et Mélisande (Pelléas) with Esham/Stratas, Braun, Kavrakos, Minton; Conlon, Galati, Israel 1994-95 - [Stravinsky] Rake’s Progress (Tom Rakewell) with Swensen, Ramey, Palmer; Davies, Vick, Hudson 2000-01 - [Harbison] The Great Gatsby (Gatsby) with Berneche, Forbis, Braun, Risley; Stahl, Lamos, Yeargan 2004-05 - [Bolcom] A Wedding (Luigi) with Malfitano, Harries, Gardner, Flannigan, Lawrence, Nolen, Cangelosi, Doss; Davies, Altman, Wagner |

BD: At what point does it cross the line and become

a fraud?

BD: At what point does it cross the line and become

a fraud? BD: Do you feel opera works well on television

now?

BD: Do you feel opera works well on television

now? JH: Werther is the prototype for all of the tragic

romantic heroes of the 19th century. When Goethe wrote the novel

— which tells the story of a man whose love for a young lady cannot

be realized in their own marriage because she is married to another man

— Werther ends up committing suicide, the ultimate act of a romantic

lover. There was a rash of suicides in Europe that resulted after

the publication of this book. Young men who were so carried away with

the emotion that they went out and killed themselves. It’s a very complex

opera and a difficult opera to realize both for Werther and for Charlotte

because she has equally as many problems as he does. In the one production

that I’ve done so far, the most difficult thing was to realize that the

problem Werther and Charlotte have is that they’re both tremendously honorable

people. At the beginning of the opera when they first meet, it’s love

at first sight, but she’s betrothed to another man.

JH: Werther is the prototype for all of the tragic

romantic heroes of the 19th century. When Goethe wrote the novel

— which tells the story of a man whose love for a young lady cannot

be realized in their own marriage because she is married to another man

— Werther ends up committing suicide, the ultimate act of a romantic

lover. There was a rash of suicides in Europe that resulted after

the publication of this book. Young men who were so carried away with

the emotion that they went out and killed themselves. It’s a very complex

opera and a difficult opera to realize both for Werther and for Charlotte

because she has equally as many problems as he does. In the one production

that I’ve done so far, the most difficult thing was to realize that the

problem Werther and Charlotte have is that they’re both tremendously honorable

people. At the beginning of the opera when they first meet, it’s love

at first sight, but she’s betrothed to another man. BD:

Do you purposely organize your career so that you have both?

BD:

Do you purposely organize your career so that you have both? BD:

Will the surtitles mean the death of opera in English?

BD:

Will the surtitles mean the death of opera in English? BD: So you will let your voice dictate what you

will sing?

BD: So you will let your voice dictate what you

will sing? JH:

What works for me is that I’m pretty clear about the repertoire that I sing.

One of the things that’s been very beneficial for me was that years ago,

after having spent a lot of time looking at the careers of singers who had

proceeded me and trying to figure out why they had the longevity that they

had, it seemed to me — and certainly this is the case

with Placido, just using him as an example — that careers

are not linear. They are series of concentric circles. By that,

I mean if you look at the career of any great singer, you find that there

is a core repertoire — those roles, those kinds of

pieces which are so suited to them, which constitute that inner circle, that

center of gravity.

JH:

What works for me is that I’m pretty clear about the repertoire that I sing.

One of the things that’s been very beneficial for me was that years ago,

after having spent a lot of time looking at the careers of singers who had

proceeded me and trying to figure out why they had the longevity that they

had, it seemed to me — and certainly this is the case

with Placido, just using him as an example — that careers

are not linear. They are series of concentric circles. By that,

I mean if you look at the career of any great singer, you find that there

is a core repertoire — those roles, those kinds of

pieces which are so suited to them, which constitute that inner circle, that

center of gravity. BD: Should the singers today not make friends

with Dominick Argento

and Robert Ward and Menotti?

BD: Should the singers today not make friends

with Dominick Argento

and Robert Ward and Menotti?

BD: Is the puzzle ever complete?

BD: Is the puzzle ever complete?

BD: You’re working too hard at it?

BD: You’re working too hard at it?

JH: That’s an interesting question. I’ve

never been asked that question before! I don’t know. If you get

down to the question of equipment, basically everybody’s born with the same

equipment. Physiologically-speaking we’re not very different, all of

us, but there are other factors that go into it that nobody yet has been able

to define. As far as the acts of making the sounds, if you have the

right person showing you what not to do to get in your own way, it is relatively

simple. It’s then you decide if you can take that and use it as a means

for expressing something. There are lots and lots of people that I

can think of from when I was in school that sang, that produced the sounds

far better than I did, far better than I ever could still, who lacked the

desire to do it. Honestly, I would have been willing to do anything

to do what I do today when I started out. I can remember when I didn’t

have any singing jobs and I was teaching part-time at the University of Connecticut.

I came to a point where they wanted to offer me a full-time position, and

it was very tempting because it was very good money, but it was not what

I wanted to do. I would rather have continued to work part-time jobs

and sling hash or whatever I had to do to continue to try to be a singer.

I’m not faulting them for this, but for whatever reason, I don’t know anybody

who really wants to do this, who really wants to do it the exclusion of everything

else, who doesn’t do it. People who tell you they didn’t make it because

of this, this, this, this, this, and have a whole list of excuses...

JH: That’s an interesting question. I’ve

never been asked that question before! I don’t know. If you get

down to the question of equipment, basically everybody’s born with the same

equipment. Physiologically-speaking we’re not very different, all of

us, but there are other factors that go into it that nobody yet has been able

to define. As far as the acts of making the sounds, if you have the

right person showing you what not to do to get in your own way, it is relatively

simple. It’s then you decide if you can take that and use it as a means

for expressing something. There are lots and lots of people that I

can think of from when I was in school that sang, that produced the sounds

far better than I did, far better than I ever could still, who lacked the

desire to do it. Honestly, I would have been willing to do anything

to do what I do today when I started out. I can remember when I didn’t

have any singing jobs and I was teaching part-time at the University of Connecticut.

I came to a point where they wanted to offer me a full-time position, and

it was very tempting because it was very good money, but it was not what

I wanted to do. I would rather have continued to work part-time jobs

and sling hash or whatever I had to do to continue to try to be a singer.

I’m not faulting them for this, but for whatever reason, I don’t know anybody

who really wants to do this, who really wants to do it the exclusion of everything

else, who doesn’t do it. People who tell you they didn’t make it because

of this, this, this, this, this, and have a whole list of excuses...

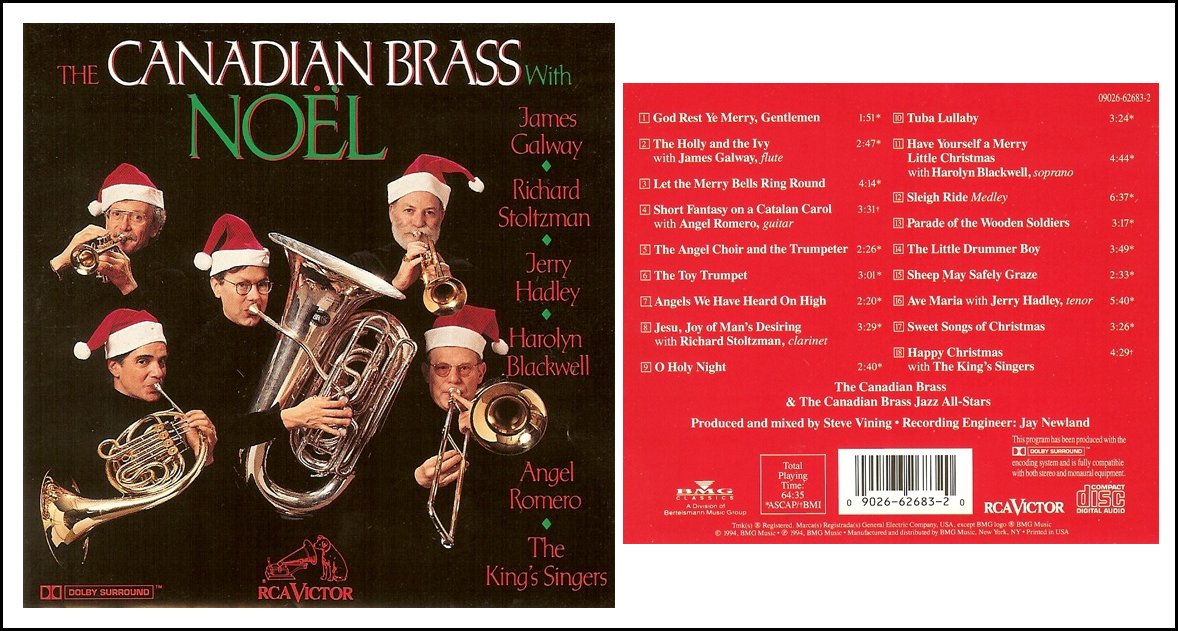

See my Interviews with Richard Stoltzman, and Angel Romero.

See my Interviews with Susan Dunn, Paul Plishka, Robert Shaw, Arleen Augér, and Tom Krause.

See my Interviews with Carol Vaness, and Kurt Masur.

See my Interviews with Alexandru Agache, Brigitte Fassbaender, Anja Silja, and Bernard Haitink.

See my Interviews with Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, Barbara Bonney, and Florence Quivar.

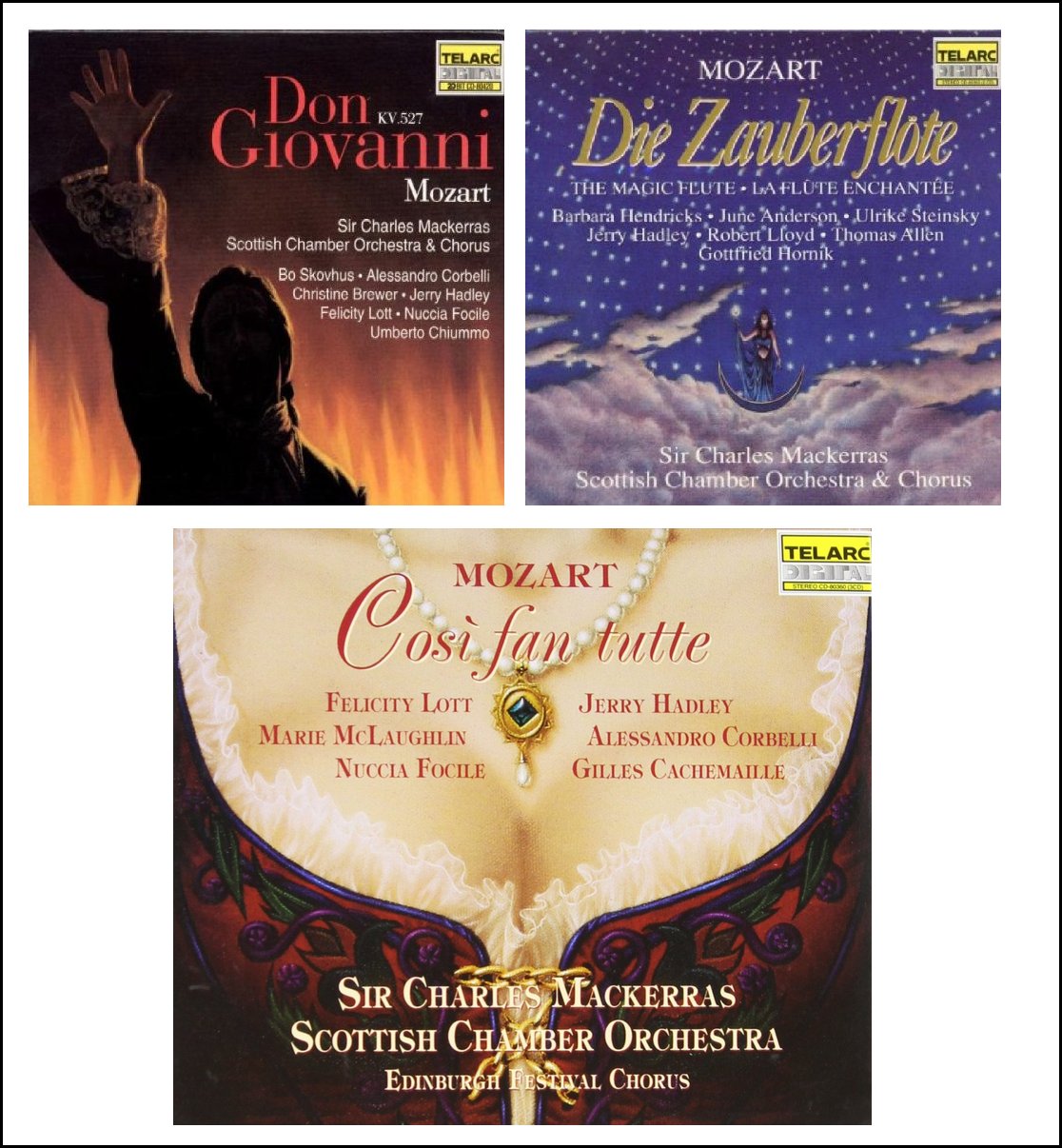

See my Interviews with Dame Felicity Lott, Sir Thomas Allen, and Sir Charles Mackerras. |

© 1987 & 1994 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on January 1, 1987 and October 13, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1991 and 1997. The transcription of the first interview was made in 1988 and published in the Massenet Newsletter in July of that year. The transcript of the second interview was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.