Paul Groves with Renée Fleming in Don

Giovanni

Winner of the 1995 Richard Tucker Foundation Award, tenor Paul Groves is making his way in the opera world. A graduate of Louisiana State University and The Juilliard School, his real start was with the Metropolitan Opera's Young Artists Development Program. Not being one of the big, heroic types, his style and grace in lyric roles have won Groves a place in the elite group of refined artists.

Besides doing leading parts at the Met, Groves has presented his Mozart and Bel Canto repertoire at La Scala, the Vienna State Opera, the Welsh National Opera, the Salzburg Festival, and the Opera Orchestra of New York. In Canada, he has appeared with the companies of Vancouver and Calgary, and back in the states, his engagements have included the Opera Theatre of St. Louis, and the Boston Lyric Opera.

Being very selective of what he presents, his diet of mostly

Mozart

is augmented with a few selected characters that suit his vocal weight

and dramatic flair. About a year ago, Paul Groves sang Nadir in

Bizet's

Pearl

Fishers with Lyric Opera of Chicago to great acclaim. It was

while he was in the Windy City that I had a chance to chat with him,

and

here is much of what we talked about that afternoon between

performances...

Bruce Duffie: You are a young man and you are a lyric tenor, so that means that you play characters that are approximately your real age and style. Do you find them more healthy or less healthy?

Paul Groves: Oh, they are more healthy. When I first started singing, I thought I would sing heavier roles like Domingo or Richard Tucker. But I realized when I got to the Met Studio that my voice suited a more light lyric sort of role like Mozart and Donizetti and Bellini. I got some very good advice from James Levine who told me I could bring a special temperament to the Mozart roles which usually is lacking. Generally we think of Don Ottavio or Tamino or Ferrando as wimpy characters. So I'm trying to bring something much more to those roles.

BD: Is there any one of these characters that you sing that's maybe too close to the real you?

PG: No, not yet. (laughter) If I were to sing Hoffman, maybe. But Don Ottavio, is very difficult because Da Ponte and Mozart didn't give us very much. He's mostly a listener. He stands on stage and listens the whole time. He's a man of honor, so it's very difficult to find something in there that I can relate to as a young, twentieth century guy.

BD: Since you bring this up, is it especially difficult to play an 18th century character for 20th century audiences, and for a 20th century singer who's gone through wars and depressions and all of this?

PG: Yes, I think it is. There are not many portrayals of 18th century people anymore. I'm not sure our audience today would be very amused by that. I think they want to see people with our kinds of emotions – you know, on the street, yelling at cab drivers. They don't want to see someone very subdued on stage. It just wouldn't come off very well.

BD: Really? You want to bring today's society onto the operatic stage?

PG: Yeah. I think that would be great.

BD: Really? I would think that we would want to get away from that when we're in the theater.

PG: No, no. It's art. Opera is art which is a reflection of today. I've done some productions by Peter Sellers that were today's society.

BD: I was going to ask if updating would help perhaps.

PG: Sometimes it does. In the case of The Pearl Fishers I don't think it would help very much. I think if you updated the story, it would just have bigger holes than it already does. But in great librettos, like Mozart's, it's fun. But we all have to remember that this is just one guy's idea. When somebody does a new production of something, it's just an idea. It's not the finished product of the piece. Here in the States, we don't take it personally. In Austria, they really take it personally when you do Mozart. This summer I did Magic Flute in a circus and they took it very personally. They hated it.

BD: (laughs) They put the circus on the stage?

PG: Yeah.

BD: You were under a big top???

PG: No, no. It was on the stage and we were all characters. Sarastro was the ring master and I was one of the clowns, and of course, Papageno was one of the clowns. But they hated it.

BD: You didn't have elephants like Aida, did you?

PG: No, but we had Sumo wrestlers. It was a good idea, and I think a lot of times that helps. Some of these productions I've found wonderful. I did a Così Fan Tutte that was updated by Christopher Alden, and it was fantastic. It was the best Così I've ever done.

BD: OK, let me ask the question – who should wind up with whom at the end?

PG: Well, I wound up with Dorabella - she's now my wife. I married her! That is where we met. But in that opera, who knows? It just depends. You can't really make a decision until you get there and see how the characters react to each other in the rehearsals and you see the chemistry. Così is one that everybody just goes through hell for an entire day, and you never really know until you get there and figure it out. For me, though, modern staging, traditional staging, it doesn't matter - as long as it's convincing, as long as the people really believe what they're saying, and are very convincing about it.

BD: Is there a secret to singing Mozart?

PG: No. There really isn't. The problem with Mozart – and people don't realize this – is that when it's sung well, it sounds easy. But it's never easy. It is the most difficult because it is so exposed that if there is one little glitch in your voice or one note that's not right on, it sticks out. In Puccini and Verdi, if you miss one little thing, you forget about it because it's just sweeping music. But in Mozart, you hear every little thing.

BD: You have to be a cleaner singer.

PG: Right. It's very difficult, even for the basses and baritones, but mostly for the sopranos and the tenors because it's all in the passagio and there's nothing high. There are no really high notes.

BD: You don't get to belt a high C?

PG: You sing F, F#, G all night long, so an A feels like a high E. (laughter) It's very difficult. I went to the dress rehearsal of Marriage of Figaro the other day and, let me tell you, Renée Fleming is the greatest Mozart singer. It's just amazing. I know that Mozart was smiling the whole time she was singing. We did Così together at the Met. It's the most fun I've ever had singing, and in a few years, we're doing a new production of Don Giovanni there. It'll be easy to be in love with Renée Fleming.

Paul Groves with Renée Fleming in Don

Giovanni

BD: Plus, you get 2 nice arias.

PG: Yeah. Mozart writes beautiful music. The problem is that there's just not enough there. I always joke with my bass friends that if Leporello was a tenor role, it would be the perfect opera.. But it's beautiful music and I enjoy doing it.

* * * * *

BD: Here in Chicago you're singing The Pearl Fishers. Is the French style very different from the other kind of elegant bel canto singing?

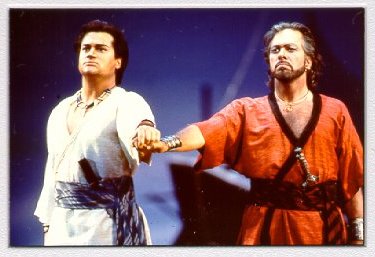

Paul Groves (left) and Gino Quilico in

The Pearl Fishers at Lyric Opera of Chicago

PG: I don't think so. There's less room for interpretation in French music. If you don't sing what's in the score - the right notes, the right rhythms - it doesn't work. It just doesn't sound right. In Verdi, of course it's better if you sing the right notes. Verdi knew what he was doing. But still, there's a certain style that is a little less clean. Maybe it's because of the singers we've had over the years who have done their own interpretations of it and we've heard it so many times.

BD: Tradition can just become memory of lots of sloppy performances.

PG: Right. That's it. But in French music, it doesn't sound good at all if you don't sing what's there in the score. Plus, it suits my voice a lot more because you're not expected to sing at full volume all the time. You have to be able to sing softly and sweetly, especially in the lighter roles.

BD: Have you done a heavy one - like Werther?

PG: No. I haven't. It's one of my favorite operas and I absolutely love it. I've been asked to do it, but I say no. I'll wait. When I feel like I've exhausted all the other things I can possibly do with all the lighter roles, then I'll do it.

BD: So you're going to put it off, say, maybe 10 years or so?

PG: Oh, yeah. I'd do Boheme before I'd do Werther. It's very heavy and very difficult, and very long. It's a very difficult role, and if you really get involved in the emotions, it can wear on you. That's what kills the voice. You don't want to see someone up there that's not involved, but real emotions in these kinds of operas are taxing on the voice.

BD: How easy is it for you to say "no" when you're offered a part?

PG: It's pretty easy because I know every opera I could sing by every composer, and I know which ones are right on the edge, like Manon. After Chicago, I'm going to do a new production of that in Berlin, but it's a special situation. The soprano is very light, everyone else in the cast is very young, and the conductor is one that will conduct it in a way that I can have a success. I feel that I can sing it.

BD: Is it a smaller theater?

PG: No, but the acoustics are very good and the size of the theater is, I believe, a myth. That doesn't matter. The orchestra is the problem. If you have a conductor that really wants the singers to be heard and really wants a wonderful dynamic performance, you can make an orchestra in the middle of Central Park very soft.

BD: So you have to really trust that conductor.

PG: Yeah, you do. And you have to trust yourself. If the orchestra is really loud and everyone is saying they're having a problem hearing me, it's not worth it to me to ruin my voice for these 4 or 5 performances screaming just because the conductor feels he can't ask the orchestra to be any softer.

BD: Do you then make a mental note about that and turn down contracts if that guy is going to be in the pit?

PG: Yes. But that's what I mean by special situations like this Manon. There are so many things I can do. I'm starting to do a lot of Gluck operas and Rameau. We're bringing back lots of things, and doing modernized staging. There are a lot of early instrument orchestras nowadays. I've just started. I've never done a Gluck piece and I'm doing 3 or 4 in the next couple of years so I'm excited about it. It's beautiful music.

BD: Have you ever talked to the French-Canadian tenor Leopold Simoneau?

PG: No, I haven't, but I certainly know who he is.

BD: He was one of the great practitioners of that kind of artistry. Do you feel you're part of a lineage of great tenors?

PG: Well . . . not really. I do think I'm in the same category of as a lot of tenors that we now really admire like Gedda, Kraus, Gigli - the kind of tenors that actually sang what was written in the music. They took chances and didn't just rely on sheer volume. They weren't about that. They were about real music and making real phrases and really communicating with the audience. Language is what I want to be remembered for. I want to have a very long career.

BD: Do you make sure, then, that you limit the number of appearances you make each year?

PG:

I haven't so far. It hasn't ever really gotten out of control for me

because

I only started about 5 years ago, and I've done mostly new

productions.

That way I spend 6 or 7 weeks just rehearsing and then have 3 or 4 or

maybe

6 performances. Then I go to a new production and I have another 6

weeks

rehearsal and then 6 performances. The problem is if you go places and

rehearse for 2 days and do 2 performances and then somewhere else for 2

days, 2 performances and in between on a night off you do a recital.

Well,

I just refuse to be that busy. If you spread yourself thin, it's just

not

possible to do your best work.

PG:

I haven't so far. It hasn't ever really gotten out of control for me

because

I only started about 5 years ago, and I've done mostly new

productions.

That way I spend 6 or 7 weeks just rehearsing and then have 3 or 4 or

maybe

6 performances. Then I go to a new production and I have another 6

weeks

rehearsal and then 6 performances. The problem is if you go places and

rehearse for 2 days and do 2 performances and then somewhere else for 2

days, 2 performances and in between on a night off you do a recital.

Well,

I just refuse to be that busy. If you spread yourself thin, it's just

not

possible to do your best work.

BD: I assume you are booked 2 or 3 years in advance now.

PG: Five, actually.

BD: Do you like knowing that on a certain Thursday in 2002 you're going to be in a certain house singing a certain role?

PG: Yeah, I do. For the next 5 years, I'm singing things I know I can do well and a lot of things I've done before, mostly the Mozart. So it doesn't bother me when you say 2002. I'll be somewhere singing Tamino. That's fine with me.

* * * * *

BD: Do you sing any new music at all?

PG: I did a new cycle by Ned Rorem in New York, and Esa-Pekka Salonen is writing an opera for the year 2001 which I'm doing with Dawn Upshaw.

BD: If he's writing it for a couple of Mozart singers, then he knows what he's doing.

PG: Yes, and he knows us both really well. He's a genius, he really is. So I think that will be great. That'll be my only new piece. Every once in awhile I take a break from Mozart - like this Pearl Fishers - but I don't mind it at all. Sometimes I go for a whole year with just Mozart. I sing Mozart in Salzburg this summer in the same production I did last summer but then for 8 months I just do one Mozart role. This Chicago engagement is a long break, but when I get back to Mozart, I breathe a sigh of relief. I do get tired of it, but every time I hear it again after a break, I fall in love with it all over again.

BD: That's the genius of Mozart.

PG: Yeah. It's incredible music. I've seen Figaro many times because my wife's done Cherubino a lot and I always go and watch her. But the other day when I saw it here, it was conducted so beautifully and sung so well – every role – that I loved it. It lasted over 4 hours and I did not want it to end. It was so great.

BD: Would you ever sing Basilio just to be in the production with her?

PG: No, but I've thought about it. Ryland Davies was great the other day. We were sitting out in the audience watching and everyone on the stage was so wonderful in each of their roles and such individual characters that I looked over at one of my friends and said, well maybe Basilio isn't such a bad idea. There are certain roles that I've been asked to do that I decline just because it doesn't seem interesting to me. I'd love to be involved in Fidelio, but the role of Jacquino is one I don't really want to do. I love Meistersinger. It's my favorite Wagner opera, but I don't want to do David, so I say no.

BD: Why not? It would seem to be a good one for you.

PG: Well, it's not suited for my voice.

BD: That's the answer then.

PG: Yeah. And these days, it's just not a role that I'd like to do. I love to watch it though. I love the opera. Every time I get a chance to see it, I go. When I was in the Met Young Artists Program, I was one of the meisters in the new production. I'll never forget when Ben Heppner came in to do the last 2 performances. We had no idea who he was. This was 7 years ago or so. We had no rehearsal with him at all. He had rehearsed with all the covers and for his first performance we were all on stage - a lot of really famous character tenors - sitting around and he walked out and started singing that first aria and our jaws just dropped. It was probably the best production in the world at that point because it was real. It was the first time anyone heard him and he was great. We all just looked at each other thinking this guy's amazing! There he is singing Wagner like Fritz Wunderlich. It was just unbelievable.

BD: He's doing a lot of these heavy roles. I hope that he lasts.

PG: He will. The thing about Ben is that he sings like a lyric tenor. He doesn't go all out, he knows what he can do. He's a smart singer.

BD: It's nice to know that you, as a Mozart tenor, revere and admire other heavier tenors and watch them and learn from them.

PG: That's one thing the Young Artist Program taught me. In my 3 years there, I learned the most just by watching. I watched people come in the first year I was there, and they were astonishing. Just the beauty of their voices and everything about them. But then you start to worry. After a while, I'd see the 2nd performance and say, ooh, that's not so good. And then 4 years later, they really weren't singing very well. Then I watched other people come in that really knew what they were doing and had taken time, learned their craft and had a lot of experience before they were thrust into the big time - like Ben. You could just tell that he was around for the long haul and that he was going to be a great one.

BD: Is it good preparation not just watching all these other singers, but doing small roles in these operas?

PG: Oh, yes. By the time I got on stage in my first leading role at the Met, I'd done 20 small roles and been on stage with Domingo, Pavarotti, all those people. I was completely comfortable. Just like my recordings. I did probably 10 small roles on recordings. So as James Levine said, by the time I go in and record Tamino, I'll know what the recording business is about. I'll know what to do and know how things work because it is completely different. But I love live performances. That's what our business is about. So what if somebody makes a mistake; so what if their voice cracks a little bit on something. I don't care. I'd rather hear a real performance with real emotion than some kind of sterile recording.

BD: Do you also do recitals?

PG: I'm doing a concert tour with my really good friend, Dwayne Croft. He's a fantastic baritone. We're doing a concert tour all over the U.S. singing mostly opera things and some Broadway songs.

BD: Are you two then going to try to be the next Domingo and Milnes, or Bjorling and Merrill?

PG: We couldn't do that, but maybe we could reach as far as Jerry Hadley and Tom Hampson. It will be fun, though. We'll have a good time. I love to sing with Dwayne - I think he's fabulous - a wonderful singer.

* * * * *

BD: Do you find that singing night after night is fun?

PG: Yeah, I enjoy this. I feel very lucky. I think about how few people get to do what I do for a living. I've done this all my life, and I get paid for it! People sing for fun - people don't ‘account' for fun. They don't sit behind a desk for fun. The only problem with our business - and it's not such a great problem that it worries me - is that there's really no family life. It's very hard to have a relationship. My wife is a singer, and we see each other quite a bit. When we're both singing in Europe, she's just an hour away.

Groves as Arturo in Bellini's I Puritani

BD: I would think that if one was a singer, the other could travel with the performer. But with both singing, and each at opposite ends of the Earth...

PG: Well, it's not so difficult because we both have our own lives. When one is a singer and the other person just travels with him or her, that other person gives up their life for the performer, and in today's world that doesn't work very well. After ten years, they get really tired of being known as Mrs. So-and-So, or Mr. So-and-So. It's a cruel world, and at parties after performance, nobody wants to talk to the spouse of this famous singer. People only want to talk to the famous singer. So, the spouses are outcasts. When I go to a party, everyone knows who my wife is, and when I go to one of hers, they know who I am, and we can still talk about opera or music or something. But my wife and I see each other a lot more than people think.

BD: Are the two of you going to give duo-recitals?

PG: I would love to, and we have done quite a few things. We did a CD of Schumann duets which got a wonderful review in the Times. It's on the Helicon label. The piano was a replica of an 1820 pianoforte. But we don't sing the same operas. She sings Charlotte in Werther and the Strauss operas.

BD: You could do the Italian Tenor...

PG: The last time I did that role, someone asked me about the man doing Faninal. They asked me if he was any good and I had to say I didn't know! I never see the second and third acts of Rosenkavalier. I have seen the opera, but I'm not really involved after my scene in the first act. It's a strange role - because it's a really beautiful piece of music, it has to be sung really well, and it's very difficult.

BD: Strauss wanted Caruso to do it, so he wrote the part for THE tenor of the day.

PG: I feel sorry for opera companies who have to pay THE tenor of the day to sing three minutes of music.

BD: The company should say, "We'll let you do five Otellos if you'll also do a couple Italian Tenors" ...

PG: But it never works out that way.

BD: Why can't opera companies be more logical?

PG: Some of them are - I think they're being forced to these days. They need to remember not to take shortcuts with valuable things like coaches.

* * * * *

BD: Does it please you to be singing in the great opera companies of the world?

PG: It's wonderful. The problem with some of the big opera companies of the world is that they skip over the artistic values. They want to sell tickets, so they insist on doing very traditional productions that don't offend anyone. It's art, and we still have to move forward even though we're doing 200 year old pieces. It can be a traditional production if it has real emotions and real acting. It doesn't have to be stolid. But some companies just don't allow for rehearsal time for these things. I was fortunate that after I finished the Met Young Artists Program, I went to Vienna and Paris and La Scala. That was the year after I finished at the Met, so I started at that level.

BD: But you had apprenticed at the top level, also. The Met Young Artist Program and the Lyric Opera Center for American Artists, and I Cadetti di La Scala, and a few other companies have training programs. Is this the advice you have for younger singers who want to sing major roles - to get involved in one of these companies?

PG: Oh definitely. The way to get involved with these major companies is to start in a summer program like Santa Fe or Glimmerglass or St. Louis. When you go to one of those places, the people in charge of the larger companies attend to find the best people for their own seasons. Then they ask you to audition, or perhaps even invite you to become a member. But it's all a network - they all talk to each other and they all talk to Europe. The heads of all these opera companies are friends. They all discuss things. So once you get into any company, my advice would be to make friends with the head of the company to discuss things and ask advice, because they know. They've usually been around this business for a long time, and they're pretty insightful about these things. Get to know them.

BD: Should you make friends with the head of the company or with the head of Artists and Repertoire?

PG: All of them! I never have understood the ‘diva' thing in opera. It's very strange to me that someone can be a normal person and after they get well known become an animal and demand things. I discuss this with my friends all the time.

BD I'll remember that and check on you in a few years...

PG: No, I'll never change. I just feel so fortunate in what I do for a living. I enjoy entertaining people. Most of us do.

BD: Well, in opera, how much is entertainment and how much is art? Where's the balance?

PG: That's the question. You want to try to do both, but sometimes it doesn't work out that way. Sometimes what we feel is a really wonderful production and what we feel is real art is not entertaining for the audience. That happens quite a few times. I get up on the stage and go through all these emotions in my head and I'm so into what I'm doing, and then realize that the audience couldn't care less. They want to be entertained. They see movies and musical theater, so opera has to be pretty fast-paced now. Things have to be going on to keep the audience interested...

BD: ...still imposed on the old Mozart tunes and Da Ponte librettos!

PG: Right. But those usually hang together because they're such brilliant pieces. Works by Leoncavallo or Ponchielli might present a problem.

BD: Are you a great tenor?

PG: Oh, I don't know. I might be in another tenor's eyes, maybe, but maybe not to the world. It's very hard to be a well-known Mozart tenor. The roles aren't such that they stand out. It's important to have someone do them well, and they're difficult to sing, but it's not going to make you into a superstar.

BD: Being a tenor, is it easier or harder dealing with the phenomenon of the Three Tenors? Does the public think you're not one of them, or do they say you're like one of them?

PG: I think they say we're like one of the three tenors. I'm one of the ones who thinks the Three Tenors is a good thing. I really do. If it gets a few people in the world interested in opera, then it's worth it. We need to do whatever we can, and luckily there seems to be a kind of revival of opera. You turn on the TV and people are singing opera in commercials. I went to a movie and there were four or five arias. In Shawshank Redemption, there was a beautiful scene from Figaro. A lot of young people will listen to it. When I walk down the street in New York, ten years ago I heard rap music coming from the headphones. Now I sometimes hear young people or business men listening to opera.

BD: Does that put bodies in the seats?

PG: I think so. I really do. If only we could get our government to give just a little more money. Take a bit away from the defense budget and put it into opera. That would be great. If the government gave more money, we could have opera companies in smaller cities, where it's impossible now. I grew up in Louisiana and went to the Baton Rouge Opera, but being a small city, it was impossible to raise enough money to keep opera in that city. Now, all the smaller companies in Louisiana have died out. They get no money from the government and it's just too difficult to get money from anywhere else. The only one left is in New Orleans. Even if the government gave much more, we'd still have to have patrons and donors to do what we want to do, but it would give an opportunity for many smaller communities to have an opera company which could do maybe two or three productions a year.

BD: Is it right that the Baton Rouge Opera Company should have to compete with the Met or Lyric Opera of Chicago that they see on the television, or with the recordings they buy in the stores?

PG: I don't think it's really a competing thing. I did productions there and they weren't of the quality of any larger company, and there's no way they could ever be. But the audience enjoyed them. They probably got more out of those performances than the average subscriber that goes every week to the Met. In New York, you don't know anyone on stage - in the chorus or the orchestra, to say nothing of the soloists. It's like going to a movie. You pay your money and expect to be entertained. When one goes to the Baton Rouge Opera, they know people onstage and in the orchestra, and they enjoyed it much more. My wife's family lives in Madison Wisconsin, and just last week we went up there for a Kurt Weill piece at the University. It wasn't the Met, but the people loved it. I heard the conversations at intermission, and they really loved it. If it's your own community and your own people, it's going to be closer to you than if you just pay and don't know any of the performers.

BD: Are you optimistic about the whole future of opera?

PG: Yeah, I am. I think it's going well - as

long as

we can get more people involved.

* * * * * * * *

After two years, Bruce Duffie returns to these pages and

resumes

his series of interviews. He is still with WNIB, Classical 97 in

Chicago.

Next time, a chat with lighting designer Duane Schuler.

= = = = =

Published in The Opera Journal, June &

September, 1998

[A double-issue]

- - - - -

= = = = = = =

- - - - -

Visit Bruce Duffie's Personal

Website [ http://www.bruceduffie.com ]